Love Your Library: February 2026

Thanks, as always, to Eleanor and Skai for posting about their recent library borrowing/reading!

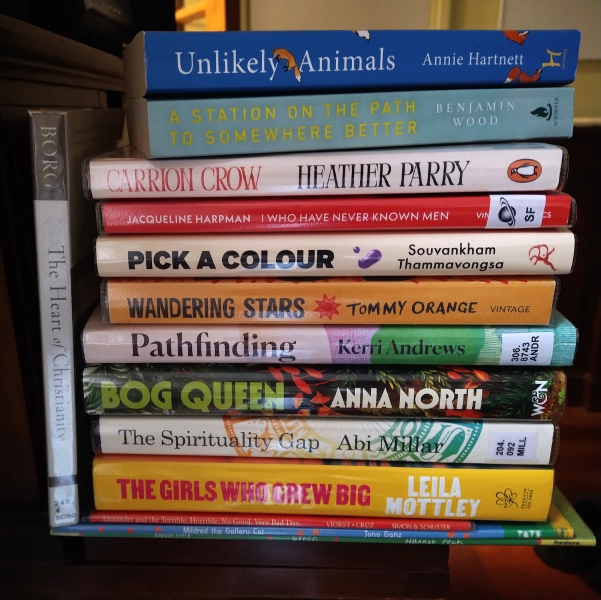

All of the books that I asked to be added to stock seemed to arrive at once. By the time I picked them up, four already had at least one further reservation on them, which was pleasing as it shows it these weren’t selfish requests; the books are of interest to others, too. Although a 2026 goal of mine was to read more from my own shelves, I’m having to balance that with big stacks of library books – which I’m glad I didn’t have to buy. A few will count towards #ReadIndies if I manage to finish them before the end of the month.

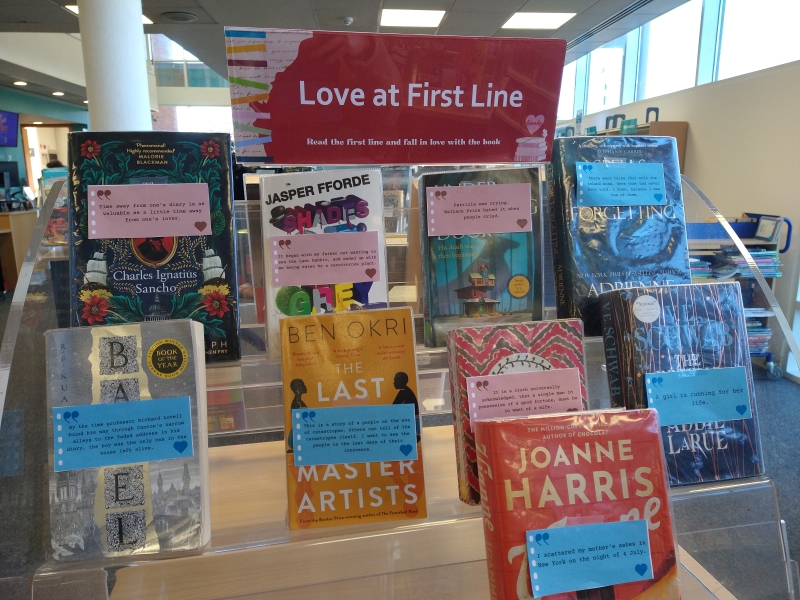

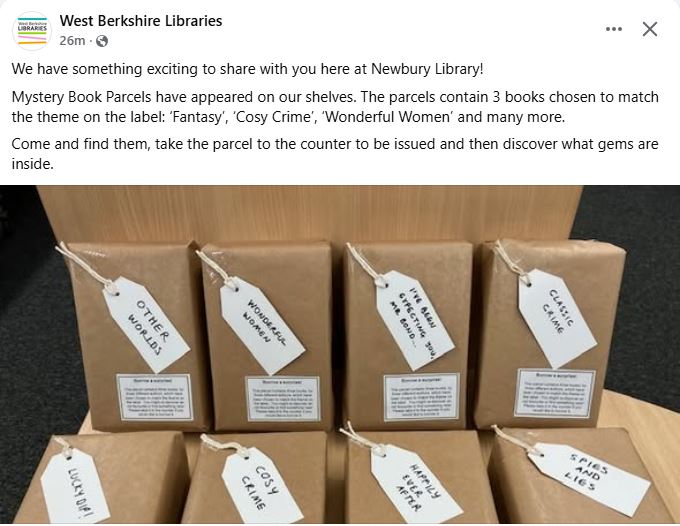

I mentioned last month that loans are down in my library system. I’ve noticed a couple of new initiatives that must be intended to boost borrowing: a “Love at First Line” Valentine’s Day display, and ‘blind date with a book’-style bundles distributed around the shelves.

One unfortunate necessity to keep stock turning over is weeding. I recently noticed that a couple of books I’d long meant to read were culled from the collection before I was able to borrow them: A Widow’s Story by Joyce Carol Oates and The Cold Millions by Jess Walter.

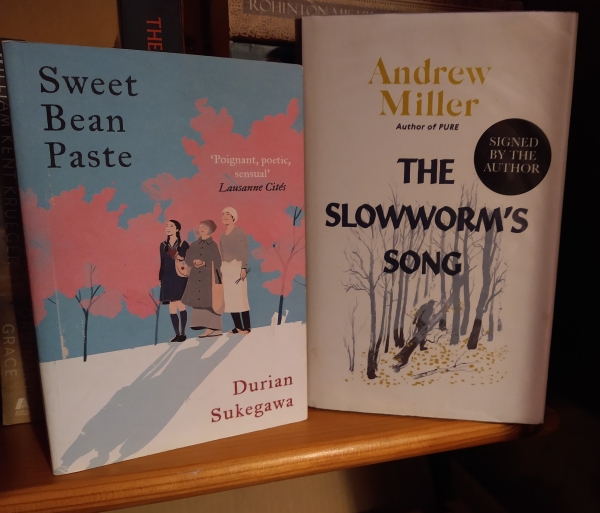

The majority of the library’s withdrawn books are sold. The latest book sale started mid-month and I was among the first through the door on that Saturday morning to have a rummage. I came away with one mostly pristine paperback (probably a rejected donation) and a signed ex-library hardback of an Andrew Miller novel for a grand total of 80 pence.

I’ve had to do some weeding myself recently, of the theology library I run at my church. We’re pushing 500 items, and given the limited space on the shelves in the lobby, I often find I’m having to wedge books in or lay them across the top. I’ve culled 24 items over the years: duplicates, books in poor condition, and a couple I labelled as irrelevant (a Barbara Pym novel set among clergy types and a book of Coronavirus prayers I’ll keep for posterity).

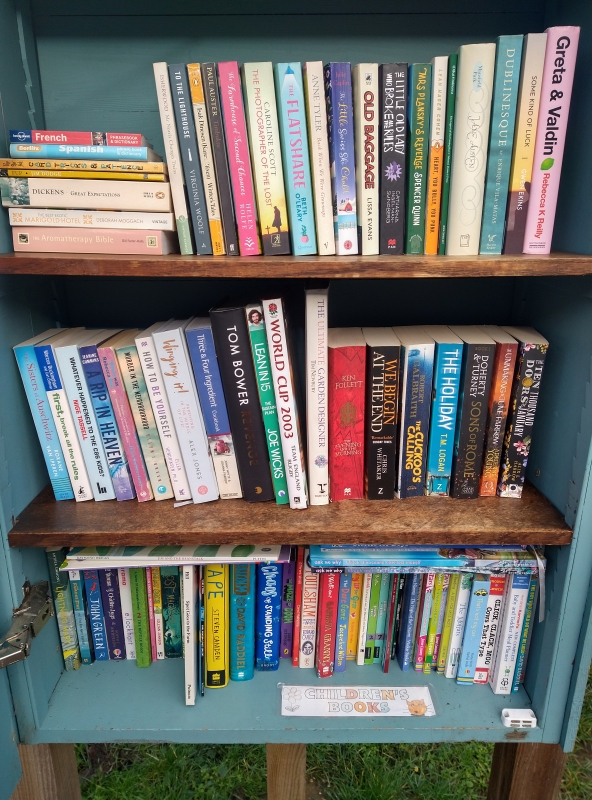

I do much more frequent culling at the neighbourhood Little Free Library I curate. Turnover is low in the winter (and I put fewer books in there than usual anyway, to try to cut down on condensation), so the same stuff often hangs around for many weeks. I immediately remove anything tatty or with a spine so faded the title is unreadable, and I try to keep only one book per author (series are frequent donations but take up too much space and don’t shift). Every so often I do a complete changeover of the stock and take the rejects to a charity warehouse or have them picked up for charity – the same strategy as with the withdrawn theology books.

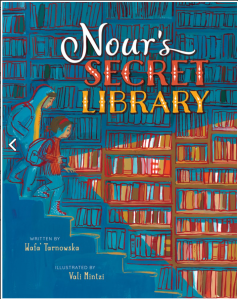

Appropriately, I found this next one among the Little Free Library donations: a sweet picture book based on the true story of how the young people of Daraya amassed a 15,000-volume basement library of rescued books during the first four years of the Syrian civil war. The author grew up during the Lebanese civil war and the illustrator in communist Romania, so they, too, know how books can give comfort and courage during the hardest times. “Their secret library had become a safe port in a sea of war. The hope it brought carried them from the darkness of destruction into a bright new dawn.” Lovely.

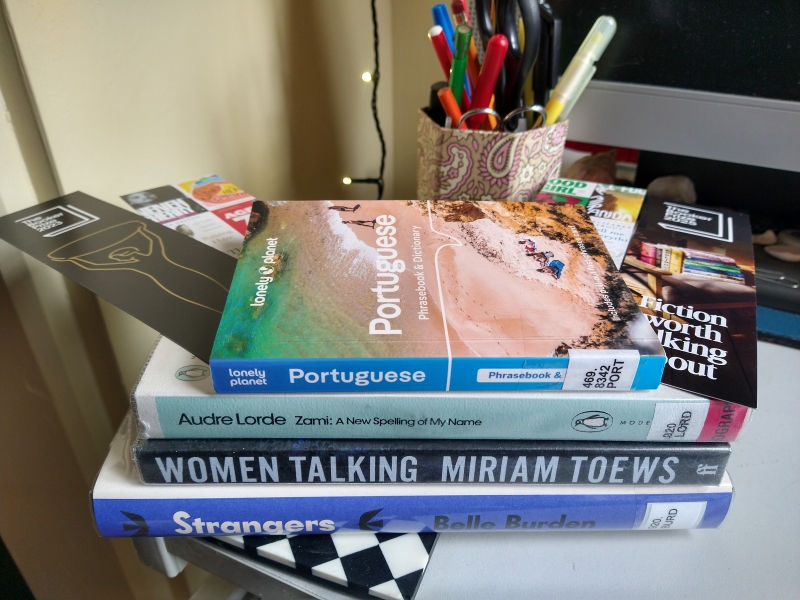

You’ll see from the Rough Guide and phrase book that we’re pondering a trip to Portugal in April. It’s feeling last minute now; we hope to book our travel and accommodation soon.

My library use over the last month:

READ

- Eva Trout by Elizabeth Bowen

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Badger Books by Paddy Donnelly

- Mildred the Gallery Cat by Jono Ganz

- Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green

- Green by Louise Greig

- I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman

- Footpath Flowers by JonArno Lawson

- An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel

- The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley

- Bog Queen by Anna North

- Winter Trees by Sylvia Plath

- Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater

- Ultra-Processed People by Chris van Tulleken

- Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst

With a cheeky Oxfam book haul (Hartnett and Wood) on the top.

CURRENTLY READING

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

- The Heart of Christianity by Marcus Borg (a reread)

- Strangers: The Story of a Marriage by Belle Burden

- Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour by Mark Haddon

- Carrie by Stephen King

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

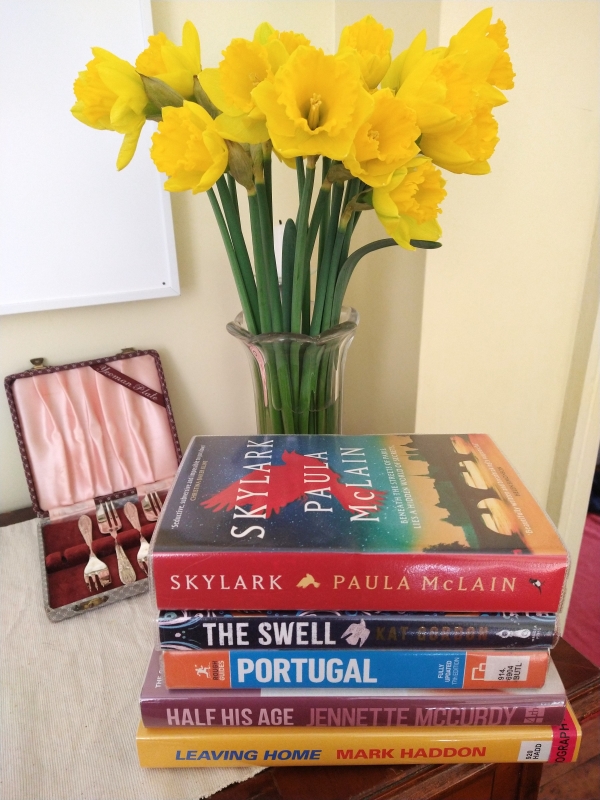

- Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy

- The Spirituality Gap by Abi Millar

- People Like Us by Jason Mott

- Pick a Colour by Souvankham Thammavongsa

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Eva Luna by Isabel Allende (for April book club)

- Pathfinding: On Walking, Motherhood and Freedom by Kerri Andrews

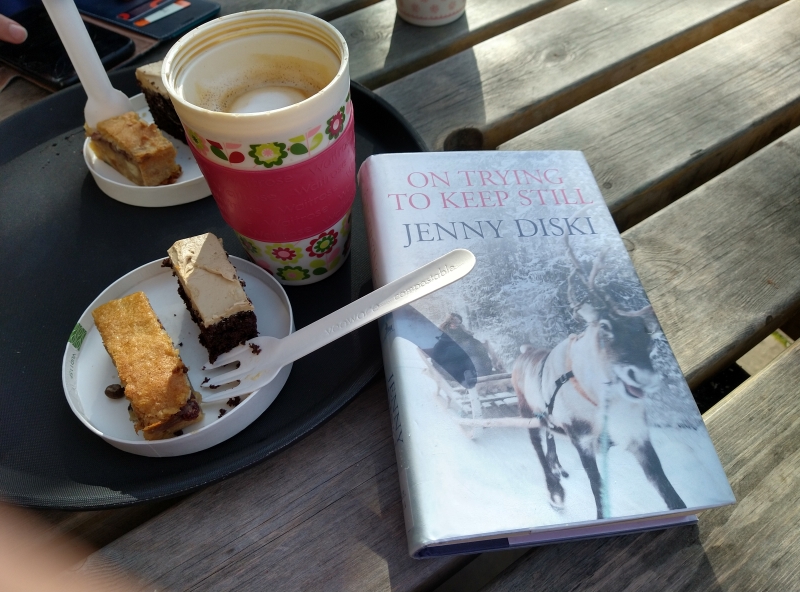

- Like Mother by Jenny Diski

- Bog Child by Siobhan Dodd

- The Swell by Kat Gordon

- Skylark by Paula McLain

- Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

- Carrion Crow by Heather Parry

- The Original by Nell Stevens

- Women Talking by Miriam Toews

- The First Day of Spring by Nancy Tucker

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Brain at Rest: Why Doing Nothing Can Change Your Life by Joseph Jebelli

- Seven by Joanna Kavenna

- Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- A Beautiful Loan by Mary Costello

- The Correspondent by Virginia Evans

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- Frostlines: An Epic Exploration of the Transforming Arctic by Neil Shea

- First Class Murder by Robin Stevens

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Redwall by Brian Jacques – I read 60 pages before this was requested off me, and I decided it was probably for the best to leave this series to my childhood.

- A Long Game: How to Write Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken – I was about halfway through when this was requested off me, but I have it from Edelweiss so can finish it on my Kindle.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Zami by Audre Lorde – I have it on my Kindle so will return this for another member of my book club (the women’s classics subgroup) to borrow as our May read.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Hay-on-Wye Trip & Book Haul (Plus a Little Life Complication)

Last week was our ninth time visiting Hay-on-Wye. Our previous trip was in October 2023 for my 40th birthday. Prompted by my overhaul post last month, I managed to finish a couple more of the 16 books I’d bought that time, taking me to 4 read and 1 skimmed; I’ve also read the first quarter of So Happy for You by Celia Laskey. Considering it was less than 18 months between visits, I’m going to call that an adequate showing. However, I will endeavour to be better about reading this latest book haul (below) in a timely fashion!

Because we were staying four nights, there was no need to rush through all the bookshops in a day or two, though that would be possible; instead, we parcelled them out and mixed up our shopping with walks, short outings in the car, and relaxing in the comfy cottage just over the English border in Cusop. I had work deadlines to meet within the first few days, but on another evening we took advantage of the place having Netflix to watch My Neighbor Totoro.

Because we were staying four nights, there was no need to rush through all the bookshops in a day or two, though that would be possible; instead, we parcelled them out and mixed up our shopping with walks, short outings in the car, and relaxing in the comfy cottage just over the English border in Cusop. I had work deadlines to meet within the first few days, but on another evening we took advantage of the place having Netflix to watch My Neighbor Totoro.

I’ve gotten secondhand book shopping in Hay down to a science over the years. Check on opening days and hours carefully or you can miss out. Thursday to Saturday is the best window to go: the Thursday market is excellent for local produce and crafts, and it’s nice to see the town bustling. (Though I’ve never seen it at Festival time, and wouldn’t want to!)

I’ve gotten secondhand book shopping in Hay down to a science over the years. Check on opening days and hours carefully or you can miss out. Thursday to Saturday is the best window to go: the Thursday market is excellent for local produce and crafts, and it’s nice to see the town bustling. (Though I’ve never seen it at Festival time, and wouldn’t want to!)

Start with the bargain options: the Little Free Library shelves by the river, where I scored Electricity by Victoria Glendinning; the sale area outside Hay Cinema Bookshop, the dedicated honesty shop beside Richard Booth’s Bookshop (new this trip), and the Book Passage beside Addyman Books – all £1/book; and the honesty shelves on the castle grounds, where it’s £2/book. Most of my purchases came from these areas. Just call me thrifty!

Next, the mid-priced options: Cinema, Broad Street Book Centre, Hay-on-Wye Booksellers, Clock Tower Books, and the new British Red Cross bookshop, which is not cheap for a charity shop but has a good selection of relatively recent stuff. (Oxfam, however, has moved away from books and primarily sells clothes, new products and bric-a-brac.) Cap it off with Addymans + Addyman Annexe, Cinema, Booth’s, the Poetry Bookshop and Green Ink Booksellers.

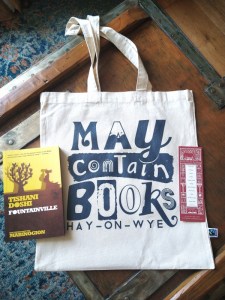

I had the best luck in Cinema this time, where I found two remainder books, three bargain books (one not pictured because it will be a gift) and the Howard Norman short stories – a particular thrill as his work is not often seen in the UK. Cinema and Booth’s are the greatest pleasure to browse. At Booth’s I bought my priciest book of the trip – Fountainville by Tishani Doshi, a retelling of stories from the Mabinogion – and indulged in a bookish tote bag (as if I needed another!). It was especially pleasing to find the Doshi and the Lewis in Hay as they are Welsh authors so will cover me for Reading Wales Month next year.

I had the best luck in Cinema this time, where I found two remainder books, three bargain books (one not pictured because it will be a gift) and the Howard Norman short stories – a particular thrill as his work is not often seen in the UK. Cinema and Booth’s are the greatest pleasure to browse. At Booth’s I bought my priciest book of the trip – Fountainville by Tishani Doshi, a retelling of stories from the Mabinogion – and indulged in a bookish tote bag (as if I needed another!). It was especially pleasing to find the Doshi and the Lewis in Hay as they are Welsh authors so will cover me for Reading Wales Month next year.

I wasn’t in the market for new books this time, not having any vouchers at my disposal, but those who are will also enjoy perusing Gay on Wye, North Books, and the large selection of new stock mixed in thematically at Booth’s. All told, that’s 15 places to shop for books.

Alas, The Bean Box, where you could get the best coffee in town, has now closed. We returned to Hay Distillery for delicious gin drinks and had Shepherd’s ice cream (a must) twice. New to us on this trip were nearby Talgarth and its excellent Mill café, the Burger Me (oh dear) restaurant at The Globe, a drink at Kilverts Inn, and an evening walk down the river to a nice shingle spit.

The weather was improbably warm and sunny – as in, I packed an umbrella and raincoat but never used them. I did need my woolly hat, scarf and gloves, but only on the first morning when we climbed up a hill. The rest of the time, it was blue skies and blossom, lambs in the fields, and 20 degrees C, for which, in early April, we could only be grateful – but also, as the lady on the till at Cinema rightly observed, it’s mildly disturbing.

This was our first major trip with our secondhand electric car, which needs rather frequent charging. En route we broke the journey at Gloucester and toured its cathedral; on the way back, we plumped for usefulness over aesthetics by stopping at carparks in Ross-on-Wye and Cirencester. We now choose routes that avoid motorways, which makes for more leisurely and scenic touring.

- Pwll y grach waterfall

Two days after we bought the car from a local acquaintance, this creature entered our lives. I certainly didn’t intend to adopt another cat a shade under six weeks after Alfie’s death. (I haven’t even finished reading Grieving the Death of a Pet on my Kindle; I still haven’t brought myself to read your kind comments on my post about losing Alfie.) But we were deeply lonely in a way we hadn’t been expecting. I would object to the use of the word “replace” – there is no replacing Alfie; we still miss him for his predictability and dignity as well as all his own funny ways. I’ve come to realize that grief is ongoing, and all of a piece: mourning Alfie took me back to the same place of grief I inhabit for my mother, and missing them and others lost in recent years is tied into my helpless sadness over natural disasters, humanitarian crises, the state of affairs in my home country, the trajectory of the planet, and on and on.

Any road, the adoption moved very quickly: from expressing interest on a Thursday to getting a call back on a Saturday to meeting and taking him home on a Sunday afternoon. Benny (“Tubbs” as was) is only a year old and full of energy. He came home with a tapeworm but got over it within a week after a targeted worming treatment. It’s been a big adjustment for us to have a cat who doesn’t sleep most of the day and can jump up onto any counter or piece of furniture. Benny considers every waking moment a chance for playtime and mischief. But he is also so sweet and affectionate. And we haven’t laughed this much in a long, long time.

We had booked the Hay trip long before we knew about Benny and were concerned it would be too soon to leave him. But we needn’t have worried; he was settled in here from Day One. Our regular cat sitter visited twice a day and he was absolutely fine. She sent us WhatsApp updates on him and cute photos, in most of which he is a blur chasing his toy snake!

So that’s what’s been going on with me. And of course, I’ve been frantically reading there in the background (36 books on the go at the moment): pre-release e-books for paid reviews, review copies I’ve been sent for the blog, new releases from the library, and the rest of the McKitterick Prize longlist – my shortlist choices are due on the 23rd, eek! I still hope to read a couple of novels from the Carol Shields Prize longlist before the winner is announced, too.

Hope everyone is having a happy spring!

Love Your Library, August 2024

It’s a Bank Holiday today here in the UK – if you have the day off, I hope you’re spending it a fun way. We’re on a day trip to Windsor Castle with friends who got free tickets through her work. Otherwise, there’s no way we would ever have gone: it’s very expensive, plus down with the monarchy and all that.

Thanks so much to Eleanor (here, here and here), Laura (the two images below) and Marcie for posting about their recent library reading!

Marina Sofia has posted a couple of relevant blogs, one a review of an Alberto Manguel book about his home library and the other a series of tempting photos of world libraries.

In the media: I loved this anti-censorship George Bernard Shaw quote posted by Book Riot on Instagram…

…and my heart was warmed by the story of Minnesota governor and current vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz installing a Little Free Library in the state capitol earlier this year. He gets my vote!

One volunteering day, a staff member told the strange-but-true story of an e-mail just received to the general libraries account. A solicitor presiding over an estate clearance let us know about a West Berkshire Libraries book found among their client’s effects, borrowed in early 1969 and never returned. Did we want it back? The consensus was that, as we’ve been doing fine without this book since BEFORE THE MOON LANDING, we will drop the issue.

Not exactly library related, but in other fun book news, I took a couple of online quizzes and got intriguing results:

My suggestion (for Angie Kim’s Happiness Falls) featured in the recent Faber Members’ summer reading recommendation round-up. And here’s that blog post I wrote for Foreword Reviews about the Bookshop Band’s new album and tour.

I’m hosting book club a week on Wednesday. Although it’s felt for a while like it might be doomed, the group has had a stay of execution at least until January. We took a break for the summer and at our July social everyone made enthusiastic noises about joining in with the four autumn and winter reads we voted on – plus we have two prospective new members who we hope will join us for the September meeting. So we’ll see how it goes.

My library use over the last month:

READ

- Private Rites by Julia Armfield

- Parade by Rachel Cusk

SKIMMED

- Nature’s Ghosts: A History – and Future – of the Natural World by Sophie Yeo

CURRENTLY READING

- One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

- Clear by Carys Davies (for September book club)

- Moominpappa at Sea by Tove Jansson

- The Garden against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

- The Burial Plot by Elizabeth Macneal

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay

- The Song of the Whole Wide World: On Motherhood, Grief, and Poetry by Tamarin Norwood

- The Echoes by Evie Wyld

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Wasteland: The Dirty Truth about What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters by Oliver Franklin-Wallis

- This Is My Sea by Miriam Mulcahy

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier

- James by Percival Everett

- Small Rain by Garth Greenwell

- Bothy: In Search of Simple Shelter by Kat Hill

- The Painter’s Daughters by Emily Howes

- Dispersals: On Plants, Borders and Belonging by Jessica J. Lee

- Held by Anne Michaels

- Playground by Richard Powers

- Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- The Accidental Garden: The Plot Thickens by Richard Mabey

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Cove: A Cornish Haunting by Beth Lynch – I enjoyed her previous memoir, and her writing is evocative, but this memoir about her return to the beloved site of childhood holidays lacks narrative drive. If you’re more familiar with the specific places, or can read it on location, you might be tempted to read the whole thing. I read 30 pages.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Some 2023 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Shortest book read this year: Pitch Black by Youme Landowne and Anthony Horton (40 pages)

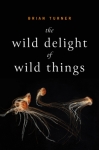

Authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood, Deborah Levy and Brian Turner (3 books each); Amy Bloom, Simone de Beauvoir, Tove Jansson, John Lewis-Stempel, W. Somerset Maugham, L.M. Montgomery and Maggie O’Farrell (2 books each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Setting aside the ubiquitous Penguin and its many imprints) Carcanet (11 books) and Picador/Pan Macmillan (also 11), followed by Canongate (7).

My top author discoveries of the year: Michelle Huneven and Julie Marie Wade

My proudest bookish accomplishment: Helping to launch the Little Free Library in my neighbourhood in May, and curating it through the rest of the year (nearly daily tidying; occasional culling; requesting book donations)

Most pinching-myself bookish moments: Attending the Booker Prize ceremony; interviewing Lydia Davis and Anne Enright over e-mail; singing carols after-hours at Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Books that made me laugh: Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson, The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt, two by Katherine Heiny, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Books that made me cry: A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney, Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout, Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Best book club selections: By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah and The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

Shortest book title encountered: Lo (the poetry collection by Melissa Crowe), followed by Bear, Dirt, Milk and They

Best 2023 book titles: These Envoys of Beauty and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore (shame the contents didn’t live up to it!)

Biggest disappointment: Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

A 2023 book that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

The worst books I read this year: Monica by Daniel Clowes, They by Kay Dick, Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy and Self-Portrait in Green by Marie Ndiaye (1-star ratings are extremely rare for me; these were this year’s four)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

20 Books of Summer, 15–17: Bill Buford, Kristin Newman, J. Courtney Sullivan

One last foodie selection for the summer: a chef’s memoir set mostly in Lyon, France. Plus a bawdy travel memoir I DNFed halfway through, and an engaging but probably overlong contemporary novel about finances, generational conflict and women’s relationships.

Dirt: Adventures in French Cooking by Bill Buford (2020)

Buford’s Heat was one of the highlights of my foodie summer reading in 2020. This is a sequel insomuch as it tells you what he did next, after his Italian-themed apprenticeships. The short answer is that he went to Lyon to learn French cooking in similarly obsessive fashion. Without knowing a word of French. And this time he had a wife and twin toddlers in tow. He met several celebrated French chefs – Michel Richard, Paul Bocuse, Daniel Boulud – and talked his way into training at a famous cookery school and in Michelin-starred kitchens.

Buford’s Heat was one of the highlights of my foodie summer reading in 2020. This is a sequel insomuch as it tells you what he did next, after his Italian-themed apprenticeships. The short answer is that he went to Lyon to learn French cooking in similarly obsessive fashion. Without knowing a word of French. And this time he had a wife and twin toddlers in tow. He met several celebrated French chefs – Michel Richard, Paul Bocuse, Daniel Boulud – and talked his way into training at a famous cookery school and in Michelin-starred kitchens.

These experiences are discussed in separate essays, so I rather lost track of the timeline. It’s odd that it took the author so many years to get around to publishing about it all. You’d think his sons were still young, but in fact they’re now approaching adulthood. The other slightly unusual thing is the amount of space Buford devotes to his pet theory that French cuisine (up to ragout, at least) evolved from Italian. Unsurprisingly, the French don’t favour this idea; I didn’t particularly care one way or the other.

Nonetheless, I enjoyed reading about his encounters with French bureaucracy; the stress of working in busy (and macho) restaurants, where he’s eventually entrusted with cooking the staff lunch; and his discovery of what makes for good bread: small wheat-growing operations rather than industrially produced flour – his ideal was the 90-cent baguette from his local boulangerie. This could have been a bit more focused, and I’m still more likely to recommend Heat, but I am intrigued to go to Lyon one day. (Secondhand gift, Christmas 2022)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman (2014)

(DNF, 156/291 pages) As featured in my Six Degrees post earlier in the month. Newman is a comedy writer for film and television (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). I liked how the title unabashedly centres things other than couplehood and procreation. When she’s travelling, she can be spontaneous, open-to-experience “Kristin-adjacent,” who loves doing whatever it is that locals do. And be a party girl, of course (“If there is one thing that is my favorite thing in the world, it’s making out on a dance floor”). However, this chronological record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. gets repetitive and raunchy. I also felt let down when I learned that she married and had a child right after she published it. So this was just her “Pietra Pan” stage before she copied everyone else. Which is fine, but were her drunken shenanigans really worth commemorating? (Secondhand, Bas Books & Home)

(DNF, 156/291 pages) As featured in my Six Degrees post earlier in the month. Newman is a comedy writer for film and television (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). I liked how the title unabashedly centres things other than couplehood and procreation. When she’s travelling, she can be spontaneous, open-to-experience “Kristin-adjacent,” who loves doing whatever it is that locals do. And be a party girl, of course (“If there is one thing that is my favorite thing in the world, it’s making out on a dance floor”). However, this chronological record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. gets repetitive and raunchy. I also felt let down when I learned that she married and had a child right after she published it. So this was just her “Pietra Pan” stage before she copied everyone else. Which is fine, but were her drunken shenanigans really worth commemorating? (Secondhand, Bas Books & Home)

Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan (2020)

I got Emma Straub vibes from this big, juicy novel focusing on two women in upstate New York: Elisabeth, a married journalist who moved out of Brooklyn when she finally conceived via IVF; and Sam, a college art student who becomes her son Gil’s babysitter. Elisabeth misses her old crowd and doesn’t fit in with the middle-aged book club ladies in her suburban neighbourhood; Sam is almost her only friend, a confidante who’s also like a little sister (better, anyway, than Elisabeth’s real sister, who lives on tropical islands and models swimwear for inspirational Instagram posts). And Sam admires Elisabeth for simultaneously managing a career and motherhood with seeming aplomb.

But fundamental differences between the two emerge, mostly to do with economics. Elisabeth comes from money and takes luxury products for granted, while Sam is solidly working-class and develops a surprising affinity with Elisabeth’s father-in-law, George, who is near bankruptcy after Uber killed off his car service business. His pet theory, “The Hollow Tree,” explains that ordinary Americans have been sold the lie that they are responsible for their own success, when really they are in thrall to corporations and the government doesn’t support them as it should. This message hits home for Sam, who is distressed about the precarious situation of the Latina dining hall employees she has met via her work study job. Both Elisabeth and Sam try to turn their privilege to the good, with varied results.

But fundamental differences between the two emerge, mostly to do with economics. Elisabeth comes from money and takes luxury products for granted, while Sam is solidly working-class and develops a surprising affinity with Elisabeth’s father-in-law, George, who is near bankruptcy after Uber killed off his car service business. His pet theory, “The Hollow Tree,” explains that ordinary Americans have been sold the lie that they are responsible for their own success, when really they are in thrall to corporations and the government doesn’t support them as it should. This message hits home for Sam, who is distressed about the precarious situation of the Latina dining hall employees she has met via her work study job. Both Elisabeth and Sam try to turn their privilege to the good, with varied results.

Although I remained engrossed in the main characters’ stories, which unfold in alternating chapters, I thought this could easily have been 300 pages instead of nearly 400. In particular, Sullivan belabours Sam’s uncertainty over her thirtysomething English fiancé, Clive, whom Elisabeth refers to as “sleazy-hot.” The red flags are more than obvious to others in Sam’s life, and to us as readers, yet we get scene after scene meant to cast shade on him. I also kept wondering if first person would have been the better delivery mode for one or both strands. Still, this was perfect literary cross-over summer reading. (Little Free Library)

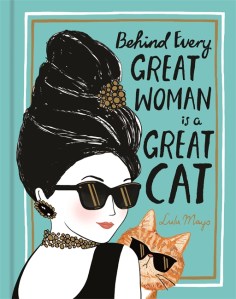

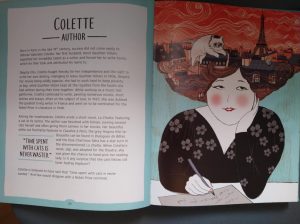

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

Last year I read the previous book,

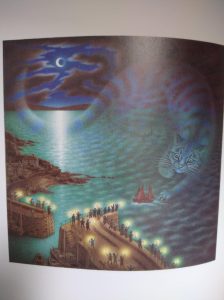

Last year I read the previous book,  The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)  Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as

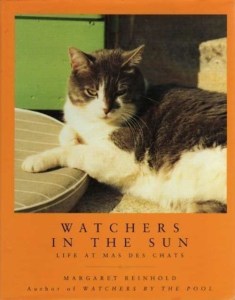

Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as  Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

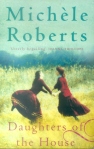

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today).

In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today). My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions.

My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions. I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)