#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

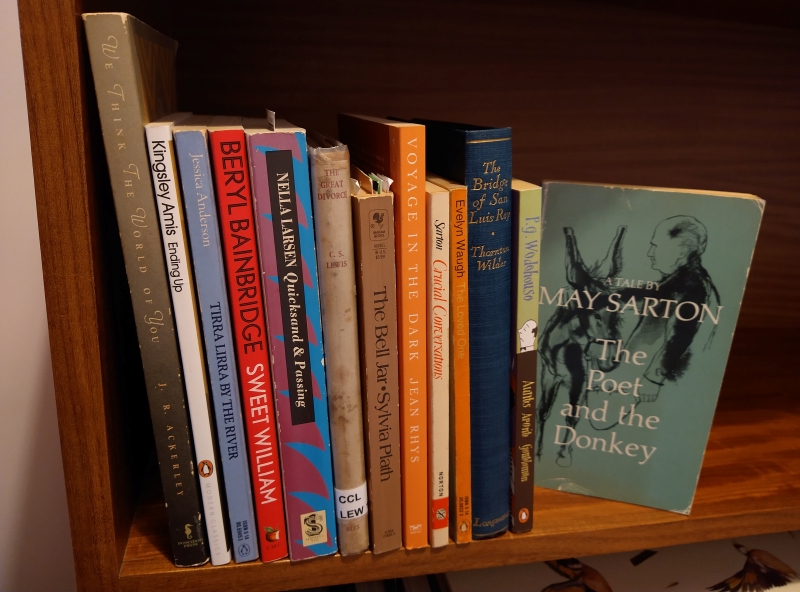

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

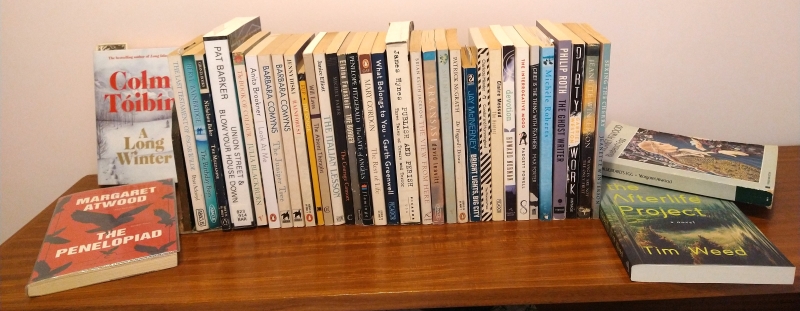

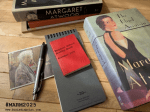

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

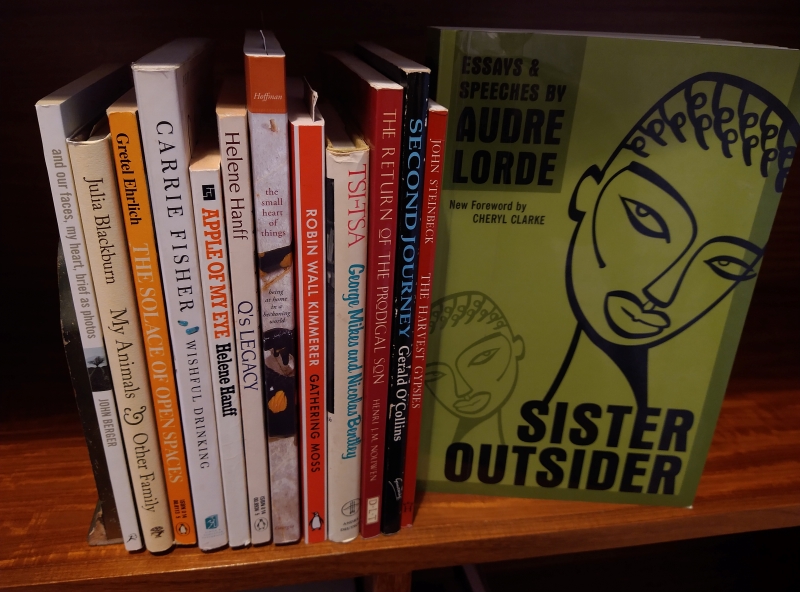

Short Nonfiction

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

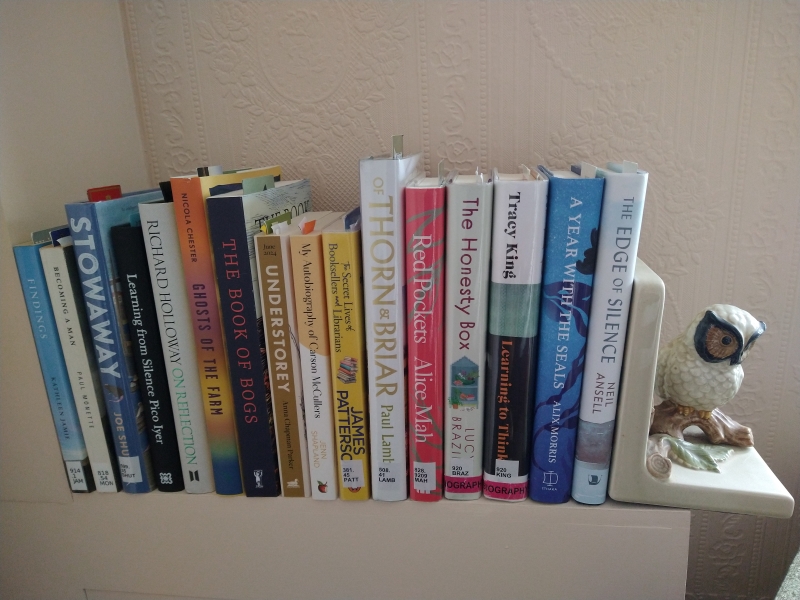

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

Novellas in November 2025 Link-Up (#NovNov25)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For the curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

Check out all the posts here:

Nine Days in Germany and What I Read, Part I: Berlin

We’ve actually been back for more than a week, but soon after our return I was felled by a nasty cold (not Covid, surprisingly), which has left me with a lingering cough and ongoing fatigue. Finally, I’m recovered just about enough to report back.

This Interrail adventure was more low-key than the one we took in 2016. The first day saw us traveling as far as Aachen, just over the border from France. It’s a nice small city with Christian and culinary history: Charlemagne is buried in the cathedral; and it’s famous for a chewy, spicy gingerbread called printen. Before our night in a chain hotel, we stumbled upon the mayor’s Green Party rally in the square – there was to be an election the following day – and drank and dined well. The Gin Library, spotted at random on the map, is an excellent and affordable Asian-fusion cocktail bar. My “Big Ben,” for instance, featured Tanqueray gin, lemon juice, honey, fresh coriander, and cinnamon syrup. Then at Hanswurst – Das Wurstrestaurant (cue jokes about finding the “worst” restaurant in Aachen!), a superior fast-food joint, I had the vegetarian “Hans Berlin,” a scrumptious currywurst with potato wedges.

The next day it was off to Berlin with a big bag of bakery provisions. For the first time, we experienced the rail cancellations and delays that would plague us for much of the next week. We then had to brave the only supermarket open in Berlin on a Sunday – the Rewe in the Hauptbahnhof – before taking the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz, the nearest station to our Airbnb flat.

It was all worth it to befriend Lemmy (the ginger one) and Roxanne. It’s a sweet deal the host has here: whenever she goes away, people pay her to look after her cats. At the same time as we were paying for a cat-sitter back home. We must be chumps!

I’ll narrate the rest of the trip through the books I read. I relished choosing relevant reads from my shelves and the library’s holdings – I was truly spoiled for choice for Berlin settings! – and I appreciated encountering them all on location.

As soon as we walked into the large airy living room of the fifth-floor Airbnb flat, I nearly laughed out loud, for there in the corner was a monstera plant. The trendy, minimalist décor, too, was just like that of the main characters’ place in…

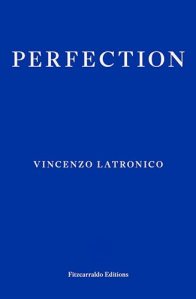

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes]

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss)

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

- Reichstag (Photos 1, 2 and 4 by Chris Foster)

- Reichstag tower designed by Norman Foster

- The Philharmonic

- Brandenburg Gate (Photos 1-3 by Chris Foster)

- Postdam’s Park Sanssouci

- Wen Cheng noodles

- Brammibal’s vegan doughnuts

I brought along another novella that proved an apt companion for our explorations of the city. Even just spotting familiar street and stop names in it felt like reassurance.

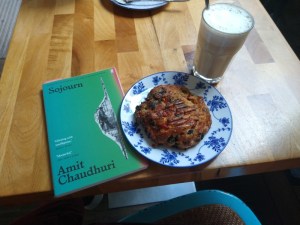

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri (2022)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library) ![]()

We spent a drizzly and slightly melancholy first day and final morning making pilgrimages to Jewish graveyards and monuments to atrocities, some of them nearly forgotten. I got the sense of a city that has been forced into a painful reckoning with its past – not once but multiple times, perhaps after decades of repression. One morning we visited the claustrophobic monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and, in the Tiergarten, the small memorials to the Roma and homosexual victims of the Holocaust. The Nazis came for political dissidents and the disabled, too, as I was reminded at the Topography of Terrors, a free museum where brutal facts are laid bare. We didn’t find the courage to go in as the timeline outside was confronting enough. I spotted links to the two historical works I was reading during my stay (Stella the red-haired Jew-catcher in the former and Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute in the latter). As I read both, I couldn’t help but think about the current return of fascism worldwide and the gradual erosion of rights that should concern us all.

Aimée and Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fischer (1994; 1995)

[Translated from German by Edna McCown]

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Milena and Margarete: A Love Story in Ravensbrück by Gwen Strauss]

The Lilac People by Milo Todd (2025)

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss)

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Under the Pink Triangle by Katie Moore (set in Dachau)]

We might have been at the Eldorado in the early 1930s on the evening when we ventured out to the bar Zosch for a “New Orleans jazz” evening. The music was superb, the German wine tasty, the whole experience unforgettable … but it sure did feel like being in a bygone era. We’re so used to the indoor smoking ban (in force in the UK since 2007) that we didn’t expect to find young people chain-smoking rollies in an enclosed brick basement, and got back to the flat with our clothes reeking and our lungs burning.

It was good to see visible signs of LGTBQ support in Berlin, though they weren’t as prevalent as I perhaps expected.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

Other Berlin highlights: a delicious vegetarian lunch at the canteen of an architecture firm, the Ritter chocolate shop, and the pigeons nesting on the flat balcony – the chicks hatched on our final morning!

And a belated contribution to Short Story September:

Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue (2006)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Trip write-up to be continued (tomorrow, with any luck)…

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

Hard to believe, but it’s nearly that time again. Autumn is drawing in. For the SIXTH year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogging and social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella technically contains 20,000 to 40,000 words, but to keep things simple we will define it as any work of under 200 pages.

This year we have two buddy reads, a 2025 fiction release and an older work of nonfiction:

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood is set in the early 1960s and features a young man who lives with his mother in northwest England and carries on the family tradition of fishing for shrimp. He longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or his chance encounter with an American filmmaker. On one pivotal day, his fortunes might just change. Check out this interview with Wood to whet your appetite. Last year our buddy read, Orbital, won the Booker Prize, auguring good things for novellas in the public sphere. Seascraper is on the longlist! In this Q&A on the Booker Prize website, Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote it. (160 pages)

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde is a 1984 collection of short pieces by the late Black lesbian feminist. I’ve only read Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, so I’m looking forward to this. From the Penguin website: “The revolutionary writings of Audre Lorde gave voice to those ‘outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women’. Uncompromising, angry and yet full of hope, this collection of her essential prose – essays, speeches, letters, interviews – explores race, sexuality, poetry, friendship, the erotic and the need for female solidarity, and includes her landmark piece ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’.” A great opportunity to tie into Nonfiction November. (190 pages)

Please join us in reading one or both books any time between now and the end of November!

You might like to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last year’s NovNov, and then finish with a New to My TBR list based on what short books others have tempted you with.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From early October a link-up post will be pinned to my site so you can add your planning posts or reviews. Keep in touch via Bluesky (@bookishbeck.bsky.social / @cathybrown746.bsky.social) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov25.

#WITMonth, II: Bélem, Blažević, Enríquez, Lebda, Pacheco and Yu (#17 of 20 Books)

Catching up with my Women in Translation month coverage, which concluded (after Part I, here) with five more short novels ranging from historical realism to animal-oriented allegory, plus a travel book.

The Rarest Fruit, or The Life of Edmond Albius by Gaëlle Bélem (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Hildegarde Serle]

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

With thanks to Europa Editions, who sent an advanced e-copy for review.

In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Croatian by Anđelka Raguž]

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez (2013; 2025)

[Translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell]

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones]

Like the Blažević, this is an impressionistic, pastoral work that contrasts vitality and decay in short chapters of one to three pages. The narrator is a young woman staying in her grandmother’s house and caring for her while she is dying of cancer; “now is not the time for life. Death – that’s what fills my head. I’m at its service. Grandma is my child. I am my grandmother’s mother. And that’s all right, I think.” The house has just four inhabitants – the narrator, Grandma Róża, Grandpa, and Ann – and seems permeable: to the cold, to nature. Animals play a large role, whether pets, farmed or wild. There’s Danube the hound, the cows delivered to the nearby slaughterhouse, and a local vixen with whom the narrator identifies.

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

In all three Linden Editions books I’ve read, the translator’s afterword has been particularly illuminating. I thought I was missing something, but Lloyd-Jones reassured me it’s unclear who Ann is: sister? friend? lover? (I was sure I spotted some homoerotic moments.) Lloyd-Jones believes she’s the mirror image of the narrator, leaning toward life while the narrator – who has endured sexual molestation and thyroid problems – tends towards death. The animal imagery reinforces that dichotomy.

The narrator and Ann remark that it feels like Grandma has been ill for a million years, but they also never want this time to end. The novel creates that luminous, eternal present. It was the best of this bunch.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews:

Pandora by Ana Paula Pacheco (2023; 2025)

[Translated from Portuguese by Julia Sanches]

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

#17 of my 20 Books of Summer:

Invisible Kitties by Yu Yoyo (2021; 2024)

[Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang]

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

I’m really pleased with myself for covering a total of 8 books for this challenge, each one translated from a different language!

Which of these would you read?

#WITMonth, Part I: Susanna Bissoli, Jente Posthuma and More

I’m starting off my Women in Translation month coverage with two short novels: one Italian and one Dutch; both about women navigating loss, family relationships, physical or mental illness, and the desire to be a writer.

Struck by Susanna Bissoli (2024; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Georgia Wall]

Vera has been diagnosed a second time with breast cancer – the same disease that felled her mother a decade ago. “I’m fed up with feeling like a problem to be taken care of,” she thinks. Even as her treatment continues, she determines to find routes to a bigger life not defined by her illness. Writing is the solution. When she moves in with her grouchy octogenarian father, Zeno Benin, she discovers he’s secretly written a novel, A Lucky Man. The almost entirely unpunctuated document is handwritten across 51 notebooks Vera undertakes to type up and edit alongside her father as his health declines.

At the same time, she becomes possessed by the legend of local living ‘saint’ Annamaria Bigani, who has been visited multiple times by the Virgin Mary and learned her date of death. Wondering if there is a story here that she needs to tell, Vera interviews Bigani, then escapes to Greece for time and creative space. “Do they save us, stories? Or is it our job to save them? I believe writing that story, day in and day out for years, saved my father’s life. But I’m sorry, I don’t have time to save his story: I need to write my own. The saint, or so I thought.” In the end, we learn, Struck – the very novel we are reading – is Vera’s book.

The title comes from a scientific study conducted on people struck by lightning at a country festival in France. How did they survive, and what were the lasting effects? The same questions apply to Vera, who avoids talking about her cancer but whose relationship with her sister Nora is still affected by choices made while their mother was alive. There are many delightful small conversations and incidents here, often involving Vera’s niece Alice. Vera’s relationship with Franco, a doctor who works with asylum seekers, is a steady part of the background. A translator’s afterword helped me understand the thought that went into how to reproduce Vera and others’ use of dialect (La Bassa Veronese vs. standard Italian) through English vernacular – so Vera and her sister say “Mam” and her father uses colourful idioms.

Though I know nothing of Bissoli’s biography, this second novel has the feeling of autofiction. Despite its wrenching themes of illness and the inevitability of death, it’s a lighthearted family story with free-flowing prose that I can enthusiastically recommend to readers of Elizabeth Berg and Catherine Newman.

This was my introduction to new (est. 2023) independent publisher Linden Editions, which primarily publishes literature in translation. I have two more of their books underway for another WIT Month post later this month. And a nice connection is that I corresponded with translator Georgia Wall when she was the publishing manager for The Emma Press.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

& Reviewed for Foreword Reviews a couple of years ago:

What I Don’t Want to Talk About by Jente Posthuma (2020; 2023)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

Both featured an unnamed narrator and a similar sense of humor. I concluded that Posthuma excels at exploring family dynamics and the aftermath of bereavement.

I got caught out when I reviewed The Appointment, too: Volckmer doesn’t technically count towards this challenge because she writes in English (and lives in London), but as she’s German, I’m adding in a teaser of my review as a bonus. Oddly, this novella did first appear in another language, French, in 2024, under the title Wonderf*ck. [The full title below was given to the UK edition.]

Calls May Be Recorded [for Training and Monitoring Purposes] by Katharina Volckmer (2025)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

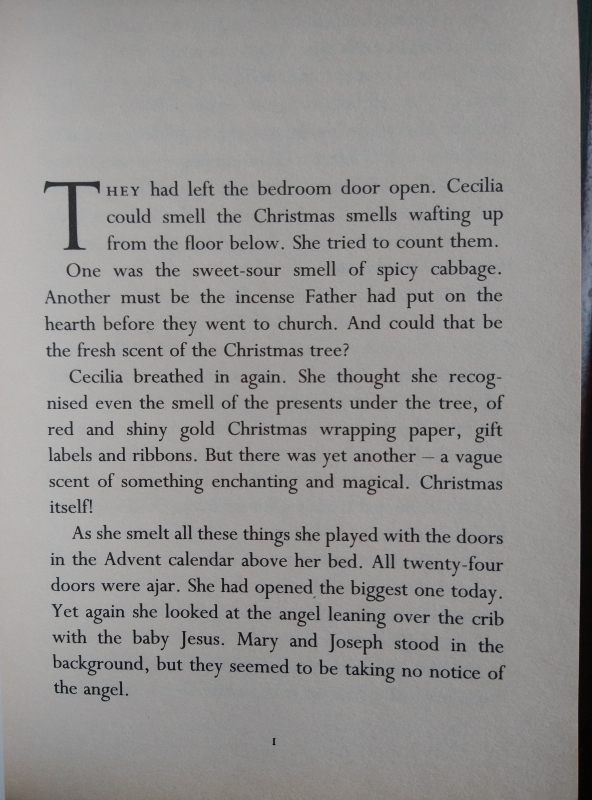

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

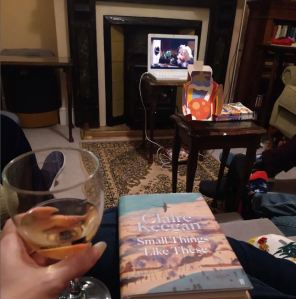

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

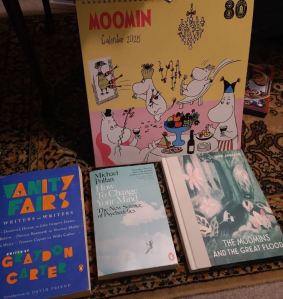

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.” Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s  Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s  Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy