Three in Translation for #NovNov23: Baek, de Beauvoir, Naspini

I’m kicking off Week 3 of Novellas in November, which we’ve dubbed “Broadening My Horizons.” You can interpret that however you like, but Cathy and I have suggested that you might like to review some works in translation and/or think about any new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas. Literature in translation is still at the edge of my comfort zone, so it’s good to have excuses such as this (and Women in Translation Month each August) to pick up books originally published in another language. Later in the week I’ll have a contribution or two for German Lit Month too.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee (2018; 2022)

[Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur]

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

There are bits of context and reflection, but I didn’t get a clear overall sense of the author as a person, just as a bundle of neuroses. Her psychiatrist tells her “writing can be a way of regarding yourself three-dimensionally,” which explains why I’ve started journaling – that, and I want believe that the everyday matters, and that it’s important to memorialize.

I think the book could have ended with Chapter 14, the note from her psychiatrist, instead of continuing with another 30+ pages of vague self-help chat. This is such an unlikely bestseller (to the extent that a sequel was published, by the same title, just with “Still” inserted!); I have to wonder if some of its charm simply did not translate. (Public library) [194 pages]

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir (2020; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Lauren Elkin]

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Whereas Sylvie loses her Catholic faith (“at one time, I had loved both Andrée and God with ferocity”), Andrée remains devout. She seems destined to follow her older sister, Malou, into a safe marriage, but before that has a couple of unsanctioned romances with her cousin, Bernard, and with Pascal (based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty). Sylvie observes these with a sort of detached jealousy. I expected her obsessive love for Andrée to turn sexual, as in Emma Donoghue’s Learned by Heart, but it appears that it did not, in life or in fiction. In fact, Elkin reveals in a translator’s note that the girls always said “vous” to each other, rather than the more familiar form of you, “tu.” How odd that such stiffness lingered between them.

This feels fragmentary, unfinished. De Beauvoir wrote about Zaza several times, including in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, but this was her fullest tribute. Its length, I suppose, is a fitting testament to a friendship cut short. (Passed on by Laura – thank you!) [137 pages]

(Introduction by Deborah Levy; afterword by Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, de Beavoir’s adopted daughter. North American title: Inseparable.)

Tell Me About It by Sacha Naspini (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford]

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The text is saturated with dialogue; quick wits and sharp tempers blaze. You could imagine this as a radio or stage play. The two characters discuss their children and the town’s scandals, including a lothario turned artist’s muse and a young woman who died by suicide. “The past is full of ghosts. For all of us. That’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be,” Loriano says. There’s a feeling of catharsis to getting all these secrets out into the open. But is there a third person on the line?

A couple of small translation issues hampered my enjoyment: the habit of alternating between calling him Loriano and Bottai (whereas Nives is always that), and the preponderance of sayings (“What’s true is that the business with the nightie has put a bee in my bonnet”), which is presumably to mimic the slang of the original but grates. Still, a good read. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!) [128 pages]

#NovNov23 Buddy Reads Reviewed: Western Lane & A Room of One’s Own

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

You may also wish to have a look at the excellent reading guide on the Booker website.

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (2023)

In the same way that you don’t have to love baseball or video games to enjoy The Art of Fielding or Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, it’s easy to warm to Western Lane even if you’ve never played squash. Debut author Chetna Maroo assumes reader unfamiliarity with her first line: “I don’t know if you have ever stood in the middle of a squash court – on the T – and listened to what is going on next door.” As Gopi looks back to the year that she was eleven – the year after she lost her mother – what she remembers is the echo of a ball hitting a wall. That first year of mourning, which was filled with compulsive squash training, reverberates just as strongly in her memory.

To make it through, Pa tells his three daughters, “You have to address yourself to something.” That something will be their squash hobby, he decides, but ramped up to the level of an obsession. Having lost my own mother just over a year ago, I could recognize in these characters the strategies people adopt to deflect grief. Keep busy. Go numb. Ignore your feelings. Get angry for no particular reason. Even within this small family, there’s a range of responses. Pa lets his electrician business slip; fifteen-year-old Mona develops a mild shopping addiction; thirteen-year-old Khush believes she still sees their mother.

Preparing for an upcoming squash tournament gives Gopi a goal to work towards, and a crush on thirteen-year-old Ged brightens long practice days. Maroo emphasizes the solitude and concentration required, alternating with the fleeting elation of performance. Squash players hover near the central T, from which most shots can be reached. Maroo, too, sticks close to the heart. Like all the best novellas, hers maintains a laser focus on character and situation. A child point-of-view can sound precocious or condescending. That is by no means the case here. Gopi’s perspective is convincing for her age at the time, yet hindsight is the prism that reveals the spectrum of intense emotions she experienced: sadness, estrangement from her immediate family, and rejection on the one hand; first love and anticipation on the other.

This offbeat, delicate coming-of-age story eschews the literary fireworks of other Booker Prize nominees. In place of stylistic flair is the sense that each word and detail has been carefully placed. Less is more. Rather than the dark horse in the race, I’d call it the reader favourite: accessible but with hidden depths. There are cinematic scenes where little happens outwardly yet what is unspoken between the characters – the gazes and tension – is freighted with meaning. (I could see this becoming a successful indie film.)

she and my uncle stood outside under the balcony of my bedroom until much later, and I knelt above them with my blanket around me. The three of us looked out at the black shapes of the rose arbour, the trees, the railway track. Stars appeared and disappeared. My knees began to ache. Below me, Aunt Ranjan wanted badly to ask Uncle Pavan how things stood now and Uncle Pavan wanted to tell her, but she wasn’t sure how to ask and he wasn’t sure how to begin. Soon, I thought, it would be morning, and night, and morning again, and it wouldn’t matter, except to someone watching from so far off that they couldn’t know yet.

The novella is illuminating on what is expected of young Gujarati women in England; on sisterhood and a bereaved family’s dynamic; but especially on what it is like to feel sealed off from life by grief. “I think there’s a glass court inside me,” Gopi says, but over the course of one quietly momentous year, the walls start to crack. (Public library) [161 pages]

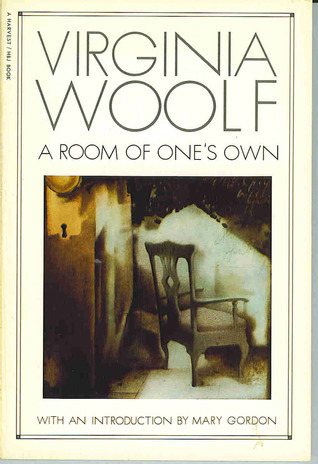

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929)

Here’s the thing about Virginia Woolf. I know she’s one of the world greats. I fully acknowledge that her books are incredibly important in the literary canon. But I find her unreadable. The last time I had any success was when I was in college. Orlando and To the Lighthouse both blew me away half a lifetime ago, but I’ve not been able to reread them or force my way through anything else (and I have tried: Mrs Dalloway, The Voyage Out and The Waves). In the meantime, I’ve read several novels about Woolf and multiple Woolf-adjacent reads (ones by Vita Sackville-West, or referencing the Bloomsbury Group). So I thought a book-length essay based on lectures she gave at Cambridge’s women’s colleges in 1928 would be the perfect point of attack.

Hmm. Still unreadable. Oh well!

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

This is important to encounter as an early feminist document, but I would have been okay with reading just the excerpts I’d already come across.

Some favourite lines:

“I thought how unpleasant it is to be locked out; and I thought how it is worse perhaps to be locked in”

“A very queer, composite being thus emerges. Imaginatively she [the woman in literature] is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history.”

“Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women, then, have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry. That is why I have laid so much stress on money and a room of one’s own.”

(Secondhand purchase many years ago) [114 pages]

Novellas in November, Week 1: My Year in Novellas (#NovNov23)

Novellas in November begins today! Cathy (746 Books) and I are delighted to be celebrating the art of the short book with you once again. Remember to let us know about your posts here, via the Inlinkz service or through a comment. How impressive is it that before November even started we were already up to 20 blog and social media posts?! I have a feeling this will be a record-breaking year for participation.

I’m kicking off our first weekly prompt:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

(See the announcement post for more info about the other weeks’ prompts and buddy reads.)

I relish building rather ludicrous stacks of novellas through the year. When I’m standing in front of a Little Free Library, browsing in secondhand bookstores and charity shops, or perusing the shelves at the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about what I could add to my piles for November.

But I do read novella-length books at other times of year, too. Forty-six of them so far this year, according to my Goodreads shelves. That seems impossible, but I guess it reflects the fact that I often choose to review novellas for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works. Here are seven highlights:

Fiction

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman: A strong short story collection with the novella-length “Indigo Run” being a Southern Gothic tale of betrayal and revenge.

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt: The heart-wrenching story of a woman who adopts her granddaughter due to her daughter’s drug addiction. Its brevity speaks emotional volumes.

Crudo by Olivia Laing: A wry, all too relatable take on recent events and our collective hypocrisy and sense of helplessness. Biography + autofiction + cultural commentary.

Nonfiction

Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop by Alba Donati: Lovely snapshots of a bookseller’s personal and professional life.

La Vie: A Year in Rural France by John Lewis-Stempel: A ‘peasant farmer’ chronicles a year in the quest to become self-sufficient. His best book in an age, ideal for armchair travel.

My Neglected Gods by Joanne Nelson: The poignant microessays locate epiphanies in the everyday.

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: A stunning autobiographical essay about the last few months of her father’s life.

I currently have five novellas underway, and I’ve laid out a pile of potential one-sitting reads for quiet mornings in the weeks to come.

Here’s hoping you all are as excited about short books as I am!

Why not share some recent favourites with us in a post of your own?

Love Your Library (and Life Update), October 2023

My thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation in this monthly meme, and to Laura for mentioning whenever she sources a book from the library!

I’m posting a bit later than usual because it’s been a busy time, and quite an emotional rollercoaster too. First was the high of my joint 40th birthday party with my husband (whose birthday is in late November) on Saturday evening. It required close to wedding levels of event planning and was stressful, especially in the week ahead, with lots of dropouts due to illness and changed plans. Yesterday and today, I’ve been up to my knees in dirty dishes, leftovers, and soiled tablecloths and bedding to try to get washed and dry. But it was a fantastic party in the end, bringing together people from lots of different areas of our lives. I’m so grateful to everyone who came to celebrate with cake, a quiz, a ceilidh, a bring-and-share/potluck meal, and dancing to the hits of 1983.

The next day was a bit of a crash back to earth as I snuck away from the house guests to attend my church’s annual Memorial Service. With All Hallows’ Eve and then All Saints coming up, it’s a traditional time to think about the dead, but all the more so because today is the first anniversary of my mother’s death. It’s taken me the full year to understand and accept, with both mind and heart, that she’s gone. I’m not marking the day in any particular way apart from having a cup of strong Earl Grey tea in her honour. I feel close to her when I read her journals, look at photographs, or see all the many items she gave me that I still use. We recently moved her remains to a different cemetery and it’s strangely comforting to think that her plot could also accommodate at least a portion of my ashes one day.

Love Your Library

Last week I was trained in how to use the library content management system and received log-ins for limited access to return, issue and renew books and search for information on the internal catalogue. It has been interesting to see how things work from the other side, having been a customer of the library system for over a decade. At busy times I will be able to help out behind the counter, but because I have to call a senior for literally anything more complicated, I am not a replacement for an employee. It is a sad reality that some libraries have to rely on volunteers in this way; none of the smaller branches in West Berkshire would be able to stay open without volunteers working alongside staff.

Novellas in November will be here before we know it. I have a huge pile of library novellas borrowed, in addition to all the ones I own.

Since last month:

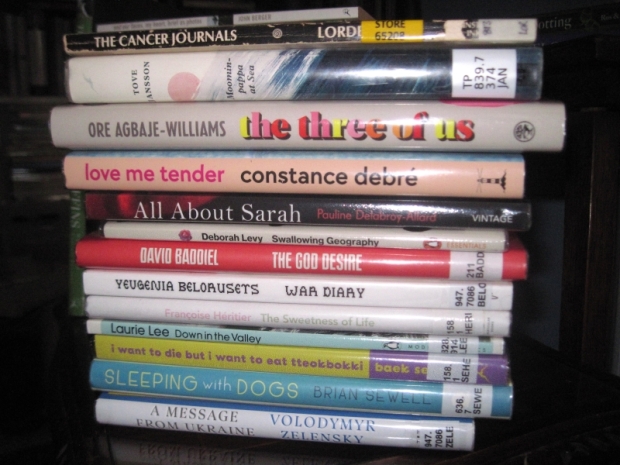

READ

- The Whispers by Ashley Audrain

- I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee

- The Seaside by Madeleine Bunting

- Penance by Eliza Clark

- Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries by Heather Fawcett

- By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah (for book club)

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- The Sad Ghost Club by Lize Meddings

CURRENTLY READING

- Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

- The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward

CURRENTLY (NOT) READING

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Coslett

- Reproduction by Louisa Hall

- Weyward by Emilia Hart

- The Last Bookwanderer by Anna James

- Findings by Kathleen Jamie (a re-read)

- Before the Light Fades by Natasha Walter

I started all of the above weeks ago, but they have been languishing on various stacks and it will take a concerted effort to get back to and finish them.

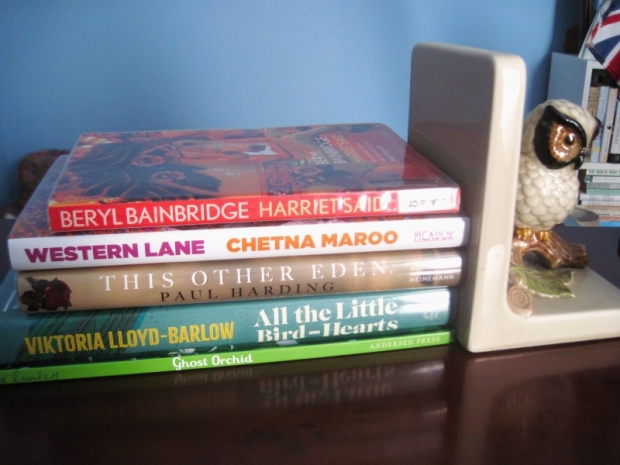

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Seventh Son by Sebastian Faulks

- This Other Eden by Paul Harding

- All the Little Bird-Hearts by Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow

All were much-hyped or prize-listed novels that didn’t grab me within the first few pages, so I relinquished them to the next person in the reservation queue.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Novellas in November 2023 Link-Up

Novellas in November had another great year, with 52 bloggers contributing a total of 175 posts! You can peruse them all at the links below.

Novellas in November Possibility Piles (#NovNov23)

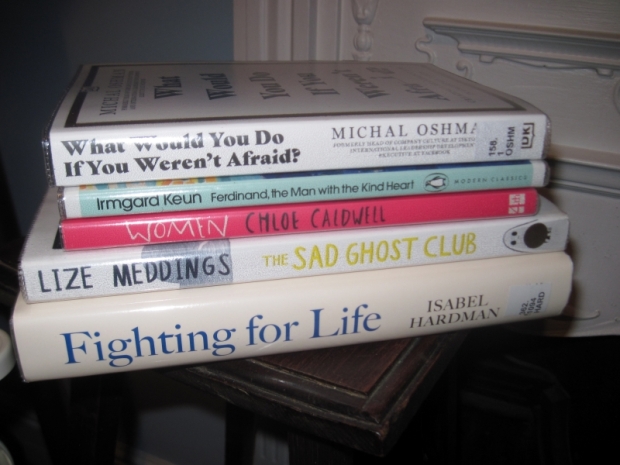

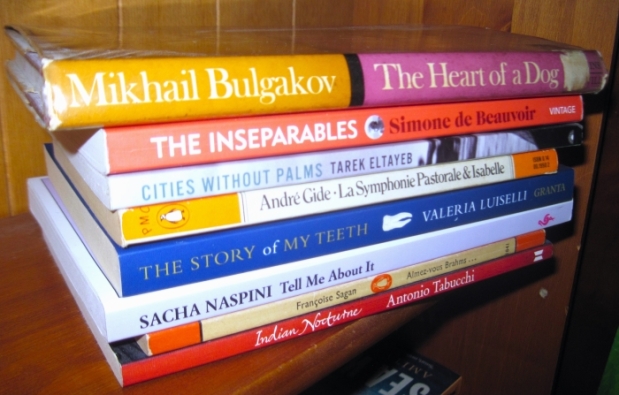

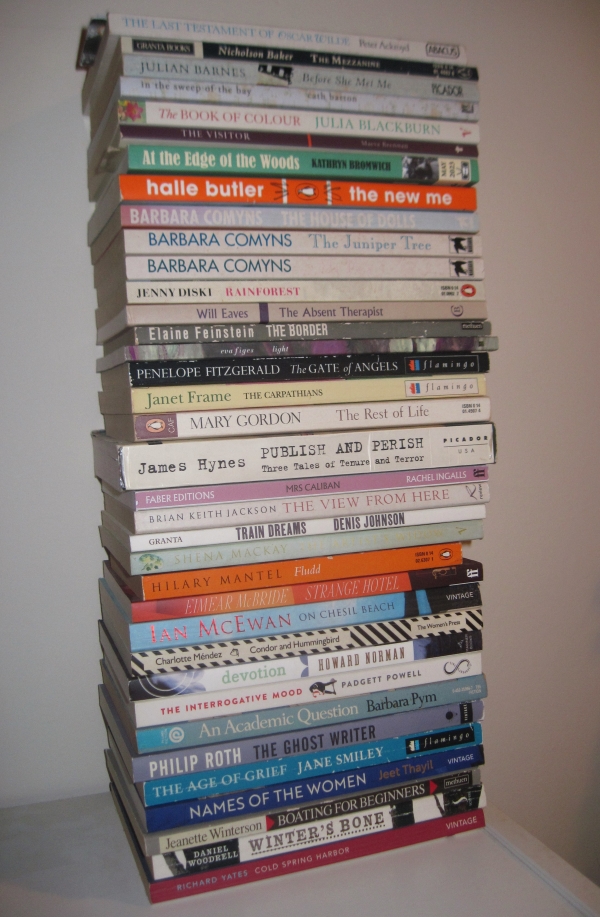

It’s less than a month now until Novellas in November (#NovNov23) begins, so Cathy and I are getting excited and making plans. I gathered up all of my potential reads of under 200 pages for a photo shoot, in rough categories as follows:

Library Haul

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Novellas in Translation

Short Nonfiction

Contemporary Novellas

I’m still awaiting various library holds, including Western Lane by Chetna Maroo, one of our buddy reads for the month; and Ferdinand: The Man with the Kind Heart by Irmgard Keun, which would do double duty for German Literature Month.

I read 29 novellas in November 2021 and 24 in November 2022. I wonder how many I’ll manage this year.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles? Give me a recommendation for what I should be sure to try to get to!

Have any novellas lined up to read next month?

Getting Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

For the fourth year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are celebrating the art of the short* book by co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long challenge. This time we have five prompts, adapted from ones commonly used for Nonfiction November. (*A reminder that we suggest 200 pages as the upper limit for a novella.)

Here’s the schedule:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

Week 2 (starts Monday 6 November): What Is a Novella?

- Ponder the definition, list favourites, or choose ones you think best capture the ‘spirit’ of a novella.

Week 3 (starts Monday 13 November): Broadening My Horizons

- Pick your top novellas in translation and think about new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas.

Week 4 (starts Monday 20 November): The Short and the Long of It

- Pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics.

Week 5 (starts Monday 27 November): New to My TBR

- In the last few days, talk about the novellas you’ve added to your TBR since the month began.

We also have two buddy read options, one contemporary and one classic. Please join us in reading one or both at any time in November!

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (2023) is on this year’s Booker Prize longlist; whether or not it advances to the shortlist on Thursday, it promises to be a one-of-a-kind debut novel about an eleven-year-old girl coming to terms with the loss of her mother and becoming deeply involved in the world of competitive squash.

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929), an extended essay about the conditions necessary for women’s artistic achievement, is based on lectures she delivered at Cambridge’s women’s colleges. This feminist classic is in print or can be freely read online (Internet Archive or Project Gutenberg Canada).

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that count towards multiple challenges? You might also consider participating in Annabel’s Beryl Bainbridge Reading Week (the 18th through 26th) as most of Bainbridge’s novels were under 200 pages.

We’re looking forward to having you join us! From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@cathy746books) and Instagram (@cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov23.

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him. Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam. – but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,  I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on. Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs. Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A  This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is. (Already featured in my

(Already featured in my  A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home. The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to  A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations. In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today).

In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today). My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions.

My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions. I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)