Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

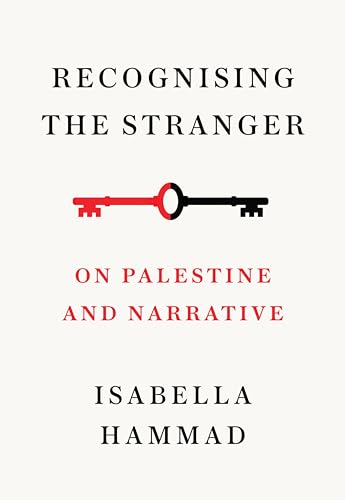

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

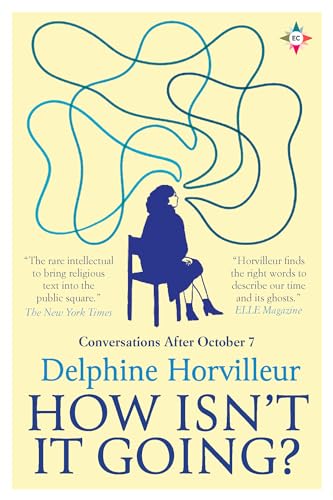

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

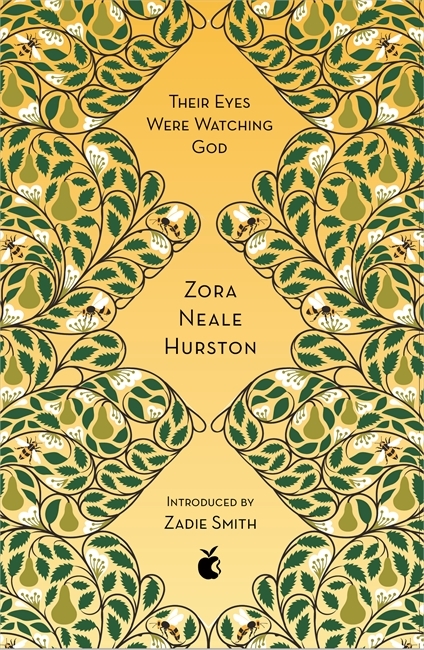

Literary Wives Club: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

This is one of those classics I’ve been hearing about for decades and somehow never read – until now. Right from the start, I could spot its influence on African American writers such as Toni Morrison. Hurston deftly reproduces the all-Black milieu of Eatonville, Florida, bringing characters to life through folksy speech and tying into a venerable tradition through her lyrical prose. As the novel opens, Janie Crawford, forty years old but still a looker, sets tongues wagging when she returns to town “from burying the dead.” Her friend Pheoby asks what happened and the narrative that unfolds is Janie’s account of her three marriages.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER!}

- To protect Janie’s reputation and prospects, her grandmother, who grew up in the time of slavery, marries Janie off to an old farmer, Logan Killicks, at age 16. He works her hard and treats her no better than one of his animals.

- She then runs off with handsome, ambitious Joe Starks. [A comprehension question here: was Janie technically a bigamist? I don’t recall there being any explanation of her getting an annulment or divorce.] He opens a general store and becomes the town mayor. Janie is, again, a worker, but also a trophy wife. While the townspeople gather on the porch steps to shoot the breeze, he expects her to stay behind the counter. The few times we hear her converse at length, it’s clear she’s wise and well-spoken, but in the 20 years they are together Joe never allows her to come into her own. He also hits her. “The years took all the fight out of Janie’s face.” When Joe dies of kidney failure, she is freer than before: a widow with plenty of money in the bank.

- Nine months after Joe’s death, Janie is courted by Vergible Woods, known to all as “Tea Cake.” He is about a decade younger than her (Joe was a decade older, but nobody made a big deal out of that), but there is genuine affection and attraction between them. Tea Cake is a lovable scoundrel, not to be trusted around money or other women. They move down to the Everglades and she joins him as an agricultural labourer. The difference between this and being Killicks’ wife is that Janie takes on the work voluntarily, and they are equals there in the field and at home.

In my favourite chapter, a hurricane hits. The title comes from this scene and gives a name to Fate. Things get really melodramatic from this point, though: during their escape from the floodwaters, Tea Cake has to fend off a rabid dog to save Janie. He is bitten and contracts rabies which, untreated, leads to madness. When he comes at Janie with a pistol, she has to shoot him with a rifle. A jury rules it an accidental death and finds Janie not guilty.

I must admit that I quailed at pages full of dialogue – dialect is just hard to read in large chunks. Maybe an audiobook or film would be a better way to experience the story? But in between, Hurston’s exposition really impressed me. It has scriptural, aphoristic weight to it. Get a load of her opening and closing paragraphs:

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Here was peace. [Janie] pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

There are also beautiful descriptions of Janie’s state of mind and what she desires versus what she feels she has to settle for. “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.” She envisions happiness as sitting under a pear tree; bees buzzing in the blossom above and all the time in the world for contemplation. (It was so pleasing when I realized this is depicted on the Virago Modern Classics cover.)

I was delighted that the question of having babies simply never arises. No one around Janie brings up motherhood, though it must have been expected of her in that time and community. Her first marriage was short and, we can assume, unconsummated; her second gradually became sexless; her third was joyously carnal. However, given that both she and her mother were born of rape, she may have had traumatic associations with pregnancy and taken pains to prevent it. Hurston doesn’t make this explicit, yet grants Janie freedom to take less common paths.

What with the symbolism, the contrasts, the high stakes and the theatrical tragedy, I felt this would be a good book to assign to high school students instead of or in parallel with something by John Steinbeck. I didn’t fall in love with it in the way Zadie Smith relates in her introduction, but I did admire it and was glad to finally experience this classic of African American literature. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- A marriage without love is miserable. Marriage is not a cure for loneliness.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the unmated? Did marriage compel love like the sun the day?

(These are rhetorical questions, but the answer is NO.)

- Every marriage is different. But it works best when there is equality of labour, status and finances. Marriage can change people.

Pheoby says to Janie when she confesses that she’s thinking about marrying Tea Cake, “you’se takin’ uh awful chance.” Janie replies, “No mo’ than Ah took befo’ and no mo’ than anybody else takes when dey gits married. It always changes folks, and sometimes it brings out dirt and meanness dat even de person didn’t know they had in ’em theyselves.”

Later Janie says, “love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch. Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

This was a perfect book to illustrate the sorts of themes we usually discuss!

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in December: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (about Sylvia Plath)

Three on a Theme: Books on Communes by Crossman, Heneghan & Twigg

Communal living always seems like a great idea but rarely works out well. Why? The short answer: Because people. A longer answer: Political ideals are hard to live out in the everyday when egos clash, practical arrangements become annoying, and lines of privacy or autonomy get crossed. All three books I review today are set in the aftermath of utopian failure. Susanna Crossman, who grew up in an English commune, looks back at 15 years of an abnormal childhood. The community in Birdeye is set to collapse after two founding members announce their departure, leaving one ageing woman and her disabled daughter. And in Spoilt Creatures, from a decade’s distance, Iris narrates the disastrous downfall of Breach House.

Home Is Where We Start: Growing up in the Fallout of the Utopian Dream by Susanna Crossman

For Crossman’s mother, “the community” was a refuge, a place to rebuild their family’s life after divorce and the death of her oldest daughter in a freak accident. For her three children, it initially was a place of freedom and apparent equality between “the Adults” and “the Kids” – who were swiftly indoctrinated into hippie opinions on the political matters of the day. “There is no difference between private and public conversations, between the inside and the outside. No euphemisms. Vaginas are discussed over breakfast alongside domestic violence and nuclear bombs.” Crossman’s present-tense recreation of her precocious eight-year-old perspective is canny, as when she describes watching Charles and Diana’s wedding on television:

It was beautiful, but I know marriage is a patriarchal institution, a capitalist trap, a snare. You can read about it in Spare Rib, or if you ask community members, someone will tell you marriage is legalized rape. It is a construction, and that means it’s not natural, and is part of the social reproduction of gender roles and women’s unpaid domestic labour.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

The author is now a clinical arts therapist, so her recreation is informed by her knowledge of healthy child development and the long-term effects of trauma. She knows the Kids suffered from a lack of routine and individually expressed love. Community rituals, such as opening Christmas presents in the middle of a circle of 40 onlookers, could be intimidating rather than welcoming. Her molestation and her sister’s rape (when she was nine years old, on a trip to India ‘supervised’ by two other adults from the community) were cloaked in silence.

Crossman weaves together memoir and psychological theory as she examines where the utopian impulse comes from and compares her own upbringing with how she tries to parent her three daughters differently at home in France. Through vignettes based on therapy sessions with patients, she shows how play and the arts can help. (I’d forgotten that I’ve encountered Crossman’s writing before, through her essay on clowning for the Trauma anthology.) I somewhat lost interest as the Kids grew into teenagers. It’s a vivid and at times rather horrifying book, but the author doesn’t resort to painting pantomime villains. Behind things were good intentions, she knows, and there is nuance and complexity to her account. It’s a great mix of being back in the moment and having the hindsight to see it all clearly.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Birdeye by Judith Heneghan

Like Crossman’s community, the Birdeye Colony is based in a big crumbling house in the countryside – but this time in the USA; the Catskills of upstate New York, to be precise. Liv Ferrars has been the de facto leader for nearly 50 years, since she was a young mother to twins. Now she’s a sixty-seven-year-old breast cancer survivor. To her amazement, her book, The Attentive Heart, still attracts visitors, “bringing their problems, their pain and loneliness, hoping to be mended, made whole.”

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

It’s a bit of a sleepy book, with a touch of suspense as secrets emerge from Birdeye’s past. I was slightly reminded of May Sarton’s Kinds of Love. I most appreciated the character study of Liv and her very different relationships with her daughters, who are approaching fifty: Mary is a capable lawyer in London, while Rose suffered oxygen deprivation at birth and is severely intellectually disabled. Since Liv’s illness, Mary has pressured her to make plans for Rose’s future and, ultimately, her own. The duty of care we bear towards others – blood family; the chosen family of friends and comrades, even pets – arises as a major theme. I’d recommend this to those who love small-town novels.

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

& 20 Books of Summer, #20:

Spoilt Creatures by Amy Twigg

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the free copy for review.

On this topic, I have also read:

Novels:

Arcadia by Lauren Groff

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne

On my TBR:

O Sinners by Nicole Cuffy

We Burn Daylight by Bret Anthony Johnston

Nonfiction:

Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk

Literary Wives Club: Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown (2019)

{SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!}

Canadian author Karma Brown’s fifth novel features two female protagonists who lived in the same house in different decades. The dual timeline, which plays out in alternating chapters, contrasts the mid-1950s and late 2010s to ask 1) whether the situation of women has really improved and 2) if marriage is always and inevitably an oppressive force.

Nellie Murdoch loves cooking and gardening – great skills for a mid-twentieth-century housewife – but can’t stay pregnant, which provokes the anger of her abusive husband, Richard. To start with, Alice Hale can’t cook or garden for toffee and isn’t sure she wants a baby at all, but as she reads through Nellie’s unsent letters and recipes, interspersed with Ladies’ Home Journal issues in the boxes in the basement, she starts to not just admire Nellie but emulate her. She’s keeping several things from her husband Nate: she was fired from her publicist job after a pre-#MeToo scandal involving a handsy male author, she’s had an IUD fitted, and she’s made zero progress on the novel she’s supposed to be writing. But Nellie’s correspondence reveals secrets that inspire Alice to compose Recipe for a Perfect Wife.

The chapter epigraphs, mostly from period etiquette and relationship guides for young wives, provide ironic commentary on this pair of not-so-perfect marriages. Brown has us wondering how closely Alice will mirror Nellie’s trajectory (aborting her pregnancy? poisoning her husband?). There were clichéd elements, such as Richard’s adultery, glitzy New York City publishing events, Alice’s quirky-funny friend, and each woman having a kindly elderly (maternal) neighbour who looks out for her and gives her valuable advice. I felt uncomfortable with how Nellie’s mother’s suicide makes it seem like Nellie’s radical acts are borne out of inherited mental illness rather than a determination to make her own path.

Often, I felt Brown was “phoning it in,” if that phrase means anything to you. In other words, playing it safe and taking an easy and previously well-trodden path. Parallel stories like this can be clever, or can seem too simple and coincidental. However, I can affirm that the novel is highly readable and has vintage charm. I always enjoy epistolary inclusions like letters and recipes, and it was intriguing to see how Nellie uses her garden herbs and flowers for pharmaceutical uses. Our first foxglove just came into flower – eek! (Kindle purchase) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- Being a wife does not have to mean being a housewife. (It also doesn’t have to mean being a mother, if you don’t want to be one.)

- Secrets can be lethal to a marriage. Even if they aren’t literally so, they’re a really bad idea.

This was, overall, a very bleak picture of marriage. In the 1950s strand there is a scene of marital rape – one of two I’ve read recently, and I find these particularly difficult to take. Alice’s marriage might not have blown up as dramatically, but still doesn’t appear healthy. She forced Nate to choose between her and the baby, and his job promotion in California. The fallout from that ultimatum is not going to make for a happy relationship. I almost thought that Nellie wields more power. However, both women get ahead through deception and manipulation. I think we are meant to cheer for what they achieve, and I did for Nellie’s revenge at Richard’s vileness, but Alice I found brattish and calculating.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

Carol Shields Prize Reading: Daughter and Dances

Two more Carol Shields Prize nominees today: from the shortlist, the autofiction-esque story of a father and daughter, both writers, and their dysfunctional family; and, from the longlist, a debut novel about the physical and emotional rigours of being a Black ballet dancer.

Daughter by Claudia Dey

Like her protagonist, Mona Dean, Dey is a playwright, but the Canadian author has clearly stated that her third novel is not autofiction, even though it may feel like it. (Fragmentary sections, fluidity between past and present, a lack of speech marks; not to mention that Dey quotes Rachel Cusk and there’s even a character named Sigrid.) Mona’s father, Paul, is a serial adulterer who became famous for his novel Daughter and hasn’t matched that success in the 20 years since. He left Mona and Juliet’s mother, Natasha, for Cherry, with whom he had another daughter, Eva. There have been two more affairs. Every time Mona meets Paul for a meal or a coffee, she’s returned to a childhood sense of helplessness and conflict.

I had a sordid contract with my father. I was obsessed with my childhood. I had never gotten over my childhood. Cherry had been cruel to me as a child, and I wanted to get back at Cherry, and so I guarded my father’s secrets like a stash of weapons, waiting for the moment I could strike.

It took time for me to warm to Dey’s style, which is full of flat, declarative sentences, often overloaded with character names. The phrasing can be simple and repetitive, with overuse of comma splices. At times Mona’s unemotional affect seems to be at odds with the melodrama of what she’s recounting: an abortion, a rape, a stillbirth, etc. I twigged to what Dey was going for here when I realized the two major influences were Hemingway and Shakespeare.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

And then there’s the King Lear setup. (I caught on to this late, perhaps because I was also reading a more overt Lear update at the time, Private Rites by Julia Armfield.) The larger-than-life father; the two older daughters and younger half-sister; the resentment and estrangement. Dey makes the parallel explicit when Mona, musing on her Hemingway-inspired oeuvre, asks, “Why had Shakespeare not called the play King Lear’s Daughters?”

Were it not for this intertextuality, it would be a much less interesting book. And, to be honest, the style was not my favourite. There were some lines that really irked me (“The flowers they were considering were flamboyant to her eye, she wanted less flamboyant flowers”; “Antoine barked. He was barking.”; “Outside, it sunned. Outside, it hailed.”). However, rather like Sally Rooney, Dey has prioritized straightforward readability. I found that I read this quickly, almost as if in a trance, inexorably drawn into this family’s drama. ![]()

Related reads: Monsters by Claire Dederer, The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright, The Wife by Meg Wolitzer, Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Farrar, Straus and Giroux for the free e-copy for review.

Also from the shortlist:

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Longlisted:

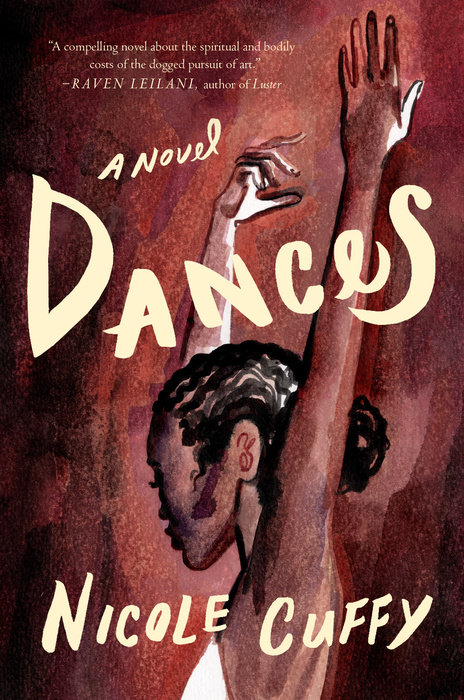

Dances by Nicole Cuffy

This was a buddy read with Laura (see her review); I think we both would have liked to see it on the shortlist as, though we’re not dancers ourselves, we’re attracted to the artistry and physicality of ballet. It’s always a privilege to get an inside glimpse of a rarefied world, and to see people at work, especially in a field that requires single-mindedness and self-discipline. Cuffy’s debut novel focuses on 22-year-old Celine Cordell, who becomes the first Black female principal in the New York City Ballet. Cece marvels at the distance between her Brooklyn upbringing – a single mother and drug-dealing older brother, Paul – and her new identity as a celebrity who has brand endorsements and gets stopped on the street for selfies.

Even though Kaz, the director, insists that “Dance has no race,” Cece knows it’s not true. (And Kaz in some ways exaggerates her difference, creating a role for her in a ballet based around Gullah folklore from South Carolina.) Cece has always had to work harder than the others in the company to be accepted:

Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

A further complication is her relationship with Jasper, her white dance partner. It’s an open secret in the company that they’re together, but to the press they remain coy. Cece’s friends Irine and Ryn support her through rocky times, and her former teachers, Luca and Galina, are steadfast in their encouragement. Late on, Cece’s search for Paul, who has been missing for five years, becomes a surprisingly major element. While the sibling bond helps the novel stand out, I most enjoyed the descriptions of dancing. All of the sections and chapters are titled after ballet terms, and even when I was unfamiliar with the vocabulary or the music being referenced, I could at least vaguely picture all the moves in my head. It takes real skill to render other art forms in words. I’ll look forward to following Cuffy’s career. ![]()

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and One World for the free e-copy for review.

Currently reading:

(Shortlist) Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote

(Longlist) Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad

Up next:

(Longlist) You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy

I’m aiming for one more batch of reviews (and a prediction) before the winner is announced on 13 May.

Literary Wives Club: Mrs. March by Virginia Feito (2021)

{SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!}

What a deliciously odd debut novel, reminiscent of Patricia Highsmith’s work for how it places a neurotic outsider at the heart of an unlikely murder investigation. George March is a popular author whose latest novel stars Johanna, a prostitute so ugly that men feel sorry for her and can’t bear to sleep with her. Meanwhile, the news cycle is consumed with the strangling of a young woman named Sylvia Gibbler in Gentry, Maine, where George goes on hunting trips with his editor. Mrs. March takes two misconceptions – that George modeled Johanna on her, and that he was somehow involved in Sylvia’s death because he kept newspaper clippings about it on his desk – and runs with them, to catastrophic effect.

Mrs. March’s usual milieu is the New York City apartment she shares with George and their son, Jonathan. Martha, the housekeeper, keeps the daily details under control, leaving Mrs. March with little to do. She doesn’t seem very interested in her son, and resents George. Each morning she walks to the bakery to buy olive bread. Every so often she’ll host an extravagant dinner party. But there is plenty of time in between to fill with flashbacks to shameful memories (having an imaginary friend, wetting the bed, her mother’s favoritism towards her sister, being raped in Cádiz) and hallucinations (a dead pigeon in the bathtub, cockroaches scuttling around the apartment). She decides to travel to Maine herself to investigate Sylvia’s death; it’s not what she finds there but what she returns to that changes things forever.

There are so many intriguing factors. One is the nebulous time period: what with Mrs. March’s fur coat and head scarf, the train cars and payphone calls, it could be the 1950s; but then there are more modern references (a washing machine, holiday flights) that made me inclined to point to the 1980s. It couldn’t be the present day unless Feito is deliberately setting the story in an alternative world without much tech. As in Highsmith, we get mistaken identity and disguises. Feito really ramps up the psychological elements, interrogating how trauma, paranoia and extreme body issues may have led to dissociation in her protagonist. Mrs. March is both obsessed with and repulsed by bodily realities. It’s only through other characters’ reactions, though, that we see just how mentally disturbed she is. Worryingly, patterns seem to be repeating with her son, who is suspended for ‘doing something’ to a girl.

I can see how this would be a divisive read: the characters are thoroughly unlikable and it can be difficult to decide what is real and what is not. Incidents I took at face value may well be symbolic, or psychological manifestations of trauma. But I found it morbidly fascinating. I never knew what was going to happen next. (Public library/NetGalley)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

In terms of Literary Wives reads, this reminded me most of The Harpy by Megan Hunter because of its eventual focus on adultery and revenge. Notably, until the very last sentence, we only know Mrs. March’s identity through her relationship to her husband. (Her first name is finally revealed to be Agatha, which of course made me think of Agatha Christie and detection, but its meaning is “good” or “honorable” – there was a martyred saint by the name.) What I took from that is that defining oneself primarily through marriage is dangerous because personality and control can be lost. This character was in need of a wider purpose to take her outside of her home and family – though those would always be her refuge to return to. Even setting Mrs. March’s mental problems aside, it is frighteningly easy to indulge in delusions about oneself or one’s spouse, so getting a reality check via communication is key.

See Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

We’ve recently acquired a new member – welcome to Kate of Books Are My Favourite and Best! – and chosen our books for the next two and a bit years. Anyone is welcome to join us in reading them. Here’s the club page on Kay’s blog, and our schedule through the end of 2026:

June 2024 Recipe for a Perfect Marriage by Karma Brown

Sept. 2024 Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Dec. 2024 Euphoria by Elin Culhed

March 2025 Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus

June 2025 The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham

Sept. 2025 Novel about My Wife by Emily Perkins

Dec. 2025 The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor

March 2026 Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell

June 2025 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

Sept. 2026 Family Family by Laurie Frankel

Dec. 2026 The Eden Test by Adam Sternbergh

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

The question posed by Claire Dederer’s third hybrid work of memoir and cultural criticism might be stated thus: “Are we still allowed to enjoy the art made by horrible people?” You might be expecting a hard-line response – prescriptive rules for cancelling the array of sexual predators, drunks, abusers and abandoners (as well as lesser offenders) she profiles. Maybe you’ve avoided Monsters for fear of being chastened about your continuing love of Michael Jackson’s music or the Harry Potter series. I have good news: This book is as compassionate as it is incisive, and while there is plenty of outrage, there is also much nuance.

Dederer begins, in the wake of #MeToo, with film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen, setting herself the assignment of re-watching their masterpieces while bearing in mind their sexual crimes against underage women. In a later chapter she starts referring to this as “the stain,” a blemish we can’t ignore when we consider these artists’ work. Try as we might to recover prelapsarian innocence, it’s impossible to forget allegations of misconduct when watching The Cosby Show or listening to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Nor is it hard to find racism and anti-Semitism in the attitude of many a mid-20th-century auteur.

Does “genius” excuse all? Dederer asks this in relation to Picasso and Hemingway, then counteracts that with a fascinating chapter about Lolita – as far as we know, Nabokov never engaged in, or even contemplated, sex with minors, but he was able to imagine himself into the mind of Humbert Humbert, an unforgettable antihero who did. “The great writer knows that even the blackest thoughts are ordinary,” she writes. Although she doesn’t think Lolita could get published today, she affirms it as a devastating picture of stolen childhood.

“The death of the author” was a popular literary theory in the 1960s that now feels passé. As Dederer notes, in the Internet age we are bombarded with biographical information about favourite writers and musicians. “The knowledge we have about celebrities makes us feel we know them,” and their bad “behavior disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms.” This is not logical, she emphasizes, but instinctive and personal. Some critics (i.e., white men) might be wont to dismiss such emotional responses as feminine. Super-fans are indeed more likely to be women or teenagers, and heartbreak over an idol’s misdoings is bound up with the adoration, and sense of ownership, of the work. She talks with many people who express loyalty “even after everything” – love persists despite it all.

U.S. cover

In a book largely built around biographical snapshots and philosophical questions, Dederer’s struggle to make space for herself as a female intellectual, and write a great book, is a valuable seam. I particularly appreciated her deliberations on the critic’s task. She insists that, much as we might claim authority for our views, subjectivity is unavoidable. “We are all bound by our perspectives,” she asserts; “consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist, which might disrupt the consuming of the art, and the biography of the audience member, which might shape the viewing of the art.”

While men’s sexual predation is a major focus, the book also weighs other sorts of failings: abandonment of children and alcoholism. The “Abandoning Mothers” chapter posits that in the public eye this is the worst sin that a woman can commit. Her two main examples are Doris Lessing and Joni Mitchell, but there are many others she could have mentioned. Even giving more mental energy to work than to childrearing is frowned upon. Dederer wonders if she has been a monster in some ways, and confronts her own drinking problem.

A painting by Cathy Lomax of girls at a Bay City Rollers concert.

Here especially, the project reminded me most of books by Olivia Laing: the same mixture of biographical interrogation, feminist cultural criticism, and memoir as in The Trip to Echo Spring and Everybody; some subjects even overlap (Raymond Carver in the former; Ana Mendieta and Valerie Solanas in the latter – though, unfortunately, these two chapters by Dederer were the ones I thought least necessary; they could easily have been omitted without weakening the argument in any way). I also thought of how Lara Feigel’s Free Woman examines her own life through the prism of Lessing’s.

The danger of being quick to censure any misbehaving artist, Dederer suggests, is a corresponding self-righteousness that deflects from our own faults and hypocrisy. If we are the enlightened ones, we can look back at the casual racism and daily acts of violence of other centuries and say: “1. These people were simply products of their time. 2. We’re better now.” But are we? Dederer redirects all the book’s probing back at us, the audience. If we’re honest about ourselves, and the people we love, we will admit that we are all human and so capable of monstrous acts.

Dederer’s prose is forthright and droll; lucid even when tackling thorny issues. She has succeeded in writing the important book she intended to. Erudite, empathetic and engaging from start to finish, this is one of the essential reads of 2023.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Buy Monsters from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both  The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.

The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.