#ReadIndies Review Catch-Up: Chevillard, Hopkins & Bateman, McGrath, Richardson

Quick thoughts on some more review catch-up books, most of them from 2025. It’s a miscellaneous selection today: absurdist flash fiction by a prolific French author, a self-help graphic novel about surviving heartbreak, a blend of bird photography and poetry, and a debut poetry collection about life and death as encountered by a parish priest.

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard (2024)

[Trans. from French by David Levin Becker]

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

With thanks to the University of Yale Press for the free copy for review.

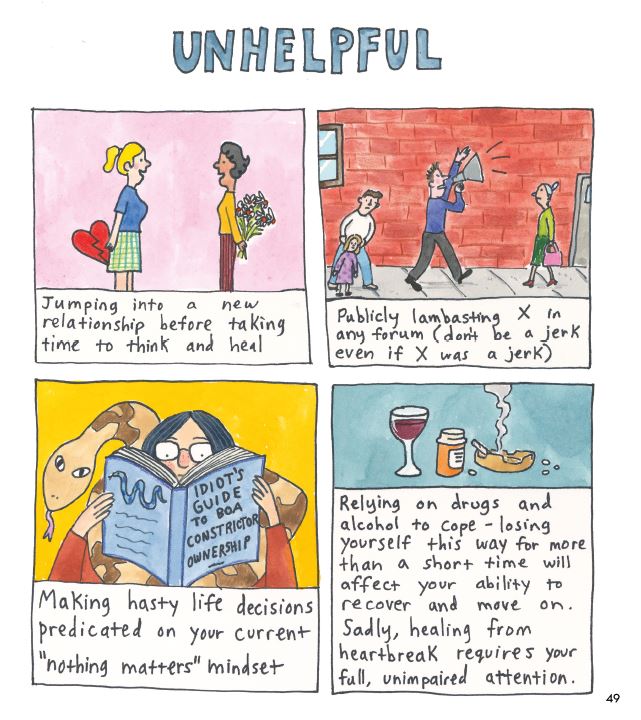

What to Do When You Get Dumped: A Guide to Unbreaking Your Heart by Suzy Hopkins; illus. Hallie Bateman (2025)

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free e-copy for review.

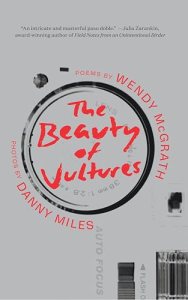

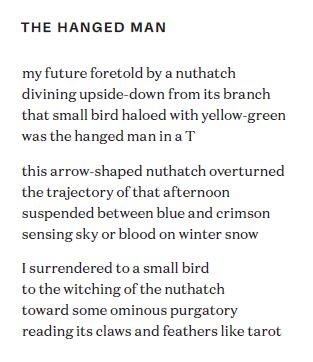

The Beauty of Vultures by Wendy McGrath; photos by Danny Miles (2025)

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

Other poems describe birds, address them directly, or take on their perspectives. Birds are a reassuring presence (cf. Ted Hughes on swifts): “I counted on our robins to return every spring” as a balm, the anxious speaker reports in “Air raid siren.” A nest of gape-mouthed baby swallows in an outhouse is the prize at the end of a long countryside walk. With its alliteration and repetition, “The Goldfinch Charm” feels like an incantation. Birds model grace (or at least the appearance of grace):

Assume a buoyancy, lightness, as though you were about to fly.

That yellow rubber duck is my surreal mythology.

Head above water. Stay calm. Paddle like crazy.

They link the natural world and the human in these gorgeous poems that interact with the images in ways that both lead and illuminate.

A female swan is a pen and eyes open

I try to write this dream:

a moment stolen or given.

Published by NeWest Press. With thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review.

Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson (2026)

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

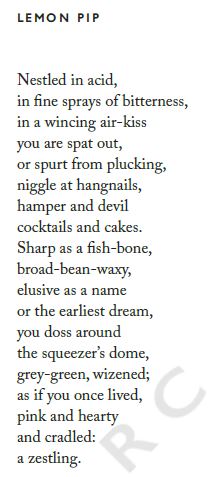

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

Richard Rohr at Greenbelt Festival (Online) & The Naked Now Review

Back in late August, I attended another online talk that really chimed with the one by Richard Holloway, this time as part of Greenbelt Festival, a progressive Christian event we used to attend annually but haven’t been to in many years now.

Not just as a Covid holdover but also in a conscious sustainability effort, Greenbelt hosted a “fly-free zone” where overseas speakers appeared on a large screen instead of travelling thousands of miles. So Richard Rohr, who appeared old and frail to me – no wonder, as he is now 81 and has survived five unrelated cancers (doctors literally want to do a genetic study on him) – appeared from the communal lounge of his Center for Action and Contemplation in New Mexico to introduce his upcoming book The Tears of Things, due in March 2025. The title is from the same Virgil quote as Holloway’s The Heart of Things. It’s about the Old Testament prophets’ shift from rage to lamentation to doxology (“the great nevertheless,” he called it): a psychological journey we all must make as part of becoming spiritually mature.

From reading his Falling Upward, I was familiar with Rohr’s central teaching of life being in two halves: the first, ego-led, is about identity and argumentation; the second is about transcending the self to tap into a universal consciousness. “It’s a terrible burden to carry your own judgementalism,” he declared. A God encounter provokes the transformation, and generally it comes through suffering, he said; you can’t take a shortcut. Anger is a mark of “incomplete” prophets such as John the Baptist, he explained. Rage might seem to empower, but it’s unrefined and only gives people permission to be nasty to others, he said. We can’t preach about a wrathful God or we will just produce wrathful people, he insisted; instead, we have to teach mercy.

When Rohr used to run rites of passage for young men, he would tell them that they weren’t actually angry, they were sad. There are tears that come from God, he said: for Gaza, for Ukraine. We know that Jesus wept at least twice, as recorded in scripture: once for Jerusalem (the collective) and once for his dead friend Lazarus (the individual). Doing the “grief work” is essential, he said. A parallel to that anger to sadness to praise trajectory is order to disorder to reorder, a paradigm he takes from the Bible’s wisdom literature. Brian McLaren’s recent work is heavily influenced by these ideas, too.

During the question time, Rohr was drawn out on the difference between Buddhism and Christianity (the latter gives reality a personal and benevolent face, he said) and how he understands hope – it is participation in the life of God, he said, and it certainly doesn’t come from looking at the data. He lauded Buddhism for its insistence on non-dualism or unitive consciousness, which he also interprets as the “mind of Christ.” The love of God is the Absolute, he said, and although he has experienced it throughout his life, he has known it especially when (as now) he was weak and poor.

Non-dualism is the theme that led me to go back to a book that had been on my bedside table, partly read, for months.

The Naked Now: Learning to See as the Mystics See (2009)

This was my fourth book by Rohr, and as with The Universal Christ, I feel at a loss trying to express how wise and earth-shaking it is. The kernel of the argument is simple. Dualistic thinking is all or nothing, us and them. The mystical view of life involves nonduality; not knowing the right things but “knowing better” through contemplation. It’s an opening of the heart that then allows for a change of mind. And yes, as he said at Greenbelt, it mostly comes about through great suffering – or great love. Jesus embodies nonduality by being not human or divine, but both, as does God through the multiplicity of the Trinity.

This was my fourth book by Rohr, and as with The Universal Christ, I feel at a loss trying to express how wise and earth-shaking it is. The kernel of the argument is simple. Dualistic thinking is all or nothing, us and them. The mystical view of life involves nonduality; not knowing the right things but “knowing better” through contemplation. It’s an opening of the heart that then allows for a change of mind. And yes, as he said at Greenbelt, it mostly comes about through great suffering – or great love. Jesus embodies nonduality by being not human or divine, but both, as does God through the multiplicity of the Trinity.

The book completely upends the fundamentalist Christianity I grew up with. Its every precept is based on Bible quotes or Christian tradition. It’s only 160 pages long, very logical and readable; I only went through it so slowly because I had to mark out and reread brilliant passages every few pages.

You can tell adult and authentic faith by people’s ability to deal with darkness, failure, and nonvalidation of the ego—and by their quiet but confident joy!

[I’ve met people who are like this.]

If your religious practice is nothing more than to remain sincerely open to the ongoing challenges of life and love, you will find God — and also yourself.

[This reminded me of “God is change,” the doctrine in Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler.]

If you can handle/ignore a bit of religion, I would recommend Rohr to readers of Brené Brown, Susan Cain (thinking of Bittersweet in particular) and Anne Lamott, among other self-help and spirituality authors – e.g., he references Eckhart Tolle. Rohr is also known for being one of the popularizers of the Enneagram, a personality tool similar to the Myers-Briggs test but which in its earliest form dates back to the Desert Father Evagrius Ponticus. ![]()

Learning How to Be Sad via Books by Susan Cain and Helen Russell

There’s been a lot of sadness in my life over the past few months. If there’s a key lesson I learned from the latest work by these authors, who are among the best self-help writers out there, it’s that denying sadness is the worst thing we could do. Accepting sadness helps us to be compassionate towards others and to acknowledge but ultimately let go of generational pain. There are measures we can take to mitigate sadness – a focus of the second half of Russell’s book – but it can’t be avoided altogether. Alongside the classics of bereavement literature I have been rereading, I found these two books to be valuable companions in grief.

Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole by Susan Cain (2022)

Cain’s Quiet must be one of the best-known nonfiction books of the millennium. It felt like vindication for introverts everywhere. Bittersweet is a little more nebulous in strategy but, boiled down, is a defence of the melancholic personality, one of the types identified by Aristotle (also explored in Richard Holloway’s The Heart of Things). Sadness is not the same as clinical depression, Cain rushes to clarify, though the two might coexist. Melancholy is often associated with creativity and sensitivity, and can lead us into empathy for others. Suffering and death seem like things to flee, but if we sit with them, we will truly be part of the human race and, per the “wounded healer” archetype, may also work toward restoration.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

Through interviews and attendance at conferences and other events, she draws in various side topics, like the longing that prompts mysticism (Kabbalah and Sufism), loving-kindness meditation, an American culture of positivity that demands “effortless perfection,” ways the business world could cultivate empathy, and how knowledge of death makes life precious. (The only chapter I found less than essential was one about transhumance – the hope of escaping death altogether. Mark O’Connell has that topic covered.) Cain weaves together her research with autobiographical material naturally. As a shy introvert with melancholy tendencies, I found both Quiet and Bittersweet comforting.

With thanks to Viking (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

How to Be Sad: The Key to a Happier Life by Helen Russell (2021)

A reread, though I only skimmed the first time around – my tiny points of criticism would be that the book is a tad long – the print in the paperback is really rather small – and retreads some of the same ground as Leap Year (e.g., how exercise and culture can contribute to a sense of wellbeing). I read that just last year, after enjoying The Year of Living Danishly with my book club. She’s a reliable nonfiction author; I’d liken her to a funnier Gretchen Rubin.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

As in her other self-help work, she interviews lots of experts and people who have gone through similar things to understand why we’re sad and what to do about it. I particularly appreciated chapters on “arrival fallacy” and “summit syndrome,” both of which refer to a feeling of letdown after we achieve what we think will make us happy, whether that be parenthood or the South Pole. Better to have intrinsic goals than external ones, Russell learns.

She also considers cultural differences in how we approach sadness: for instance, Russians relish sadness and teach their children to do the same, whereas the English, especially men, are expected to bury their feelings. Russell notes a waning of the rituals that could help us cope with loss, and a rise in unhealthy coping mechanisms. Like Cain, she also covers sad music (vs. one of her interviewees prescribing Jack Johnson as a mood equalizer). There are lots of laughs to be had, but the epilogue can’t fail to bring a tear to the eye. (Public library)

Both:

I found this quote from the Russell a handy summary of both authors’ premise. Dr Lucy Johnstone says:

“The key question when encountering someone with mental or emotional distress shouldn’t be, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ but rather, ‘What’s happened to you?’”

Suffering is coming for all of us, so why not arm yourself to deal with it and help others through? That’s always been one of my motivations for reading widely: to understand other people’s situations and prepare myself for what the future holds.

Could you see yourself reading a book about sadness?

The Swedish Art of Ageing Well by Margareta Magnusson (#NordicFINDS23)

Annabel’s Nordic FINDS challenge is running for the second time this month. I hope to manage at least one more read for it; this one feels like a cheat as it’s not exactly in translation. Magnusson, who is Swedish, either wrote it in English or translated it herself for simultaneous 2022 publication in Sweden and the USA – where the title phrase was “Aging Exuberantly.” There is some quirky phrasing that a native speaker would never use, more so than in her Döstädning: The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning, which I reviewed last year, but it’s perfectly understandable.

The subtitle is “Life wisdom from someone who will (probably) die before you,” which gives a flavour of 89-year-old Magnusson’s self-deprecating sense of humour. The big 4-0 is coming up for me later this year, but I’ve been reading books about ageing and death since my twenties and find them valuable for gaining perspective and storing up wisdom.

This is not one of those “hygge” books extolling the virtues of Scandinavian culture, but rather a charming self-help memoir recounting what the author has learned about what matters in life and how to gracefully accept the ageing process. Each chapter is like a mini essay with a piece of advice as the title. Some are more serious than others: “Don’t Fall Over” and “Keep an Open Mind” vs. “Eat Chocolate” and “Wear Stripes.”

Since Magnusson was widowed, she has valued her friendships all the more, and during the pandemic cheerfully switched to video chats (G&T in hand) with her best friend since age eight. She is sweetly optimistic despite news headlines; after all, in the words of one of her chapter titles, “The World Is Always Ending” – she grew up during World War II and remembers the bad old days of the Cold War and personal near-tragedies like when the ship on which her teenage son was a deckhand temporarily disappeared in the South China Sea.

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Volunteering, spending lots of time with younger people, looking after another living thing (a houseplant if you can’t commit to a pet), turning daily burdens into beloved routines, and keeping your hair looking as nice as possible are some of Magnusson’s top tips for coping.

An appendix gives additional death-cleaning guidance based on Covid-era FAQs; the chapter in this book that is most reminiscent of the practical approach of Döstädning is “Don’t Leave Empty-Handed,” which might sound metaphorical but in fact is a literal mantra she learned from an acquaintance. On a small scale, it might mean tidying a room gradually by picking up at least one item each time you pass through; more generally, it could refer to a mindset of cleaning up after oneself so that the world is a better place for one’s presence.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Miscellaneous Novellas: Jungle Nama, The Magic Pudding, Tree Glee (#NovNov22)

Here’s a random trio of short books I read earlier and haven’t managed to review until now. Novellas in November is a deliberately wide-ranging challenge, taking in almost any genre you care to read – here I have a retold fable, a bizarre children’s classic, and a self-help work celebrating our connection with trees. I’ll do a couple more of these miscellaneous round-ups before the end of the month.

Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sunderban by Amitav Ghosh (2021)

My first from Ghosh. It’s a retelling in verse of a local Indian legend about Dhona, a greedy merchant who arrives in the mangrove swamps to exploit their resources. To gain wealth he is willing to sacrifice his destitute cousin, Dhukey, to placate Dokkhin Rai, a jungle-dwelling demon that takes the form of a man-eating tiger.

My first from Ghosh. It’s a retelling in verse of a local Indian legend about Dhona, a greedy merchant who arrives in the mangrove swamps to exploit their resources. To gain wealth he is willing to sacrifice his destitute cousin, Dhukey, to placate Dokkhin Rai, a jungle-dwelling demon that takes the form of a man-eating tiger.

However, Dhukey’s mother, distrustful of their cousin, prepared her son for trouble, telling him that if he calls on the goddess Bon Bibi in dwipodi-poyar (rhyming couplets of 24 syllables), she will rescue him. I loved this idea of poetry itself saving the day.

The legend is told, then, in that very Bengali verse style. The insistence on rhyme sometimes necessitates slightly silly word choices, but the text feels very musical. Beyond the fairly obvious messages of forgiveness—

But you must forgive him, rascal though he is;

to hate forever is to fall into an abyss.

—and not grasping for more than you need—

All you need do, is be content with what you’ve got;

to be always craving more, is a demon’s lot.

—I appreciated the idea of ordered verse replicating, or even creating, the order of nature:

Thus did Bon Bibi create a dispensation,

that brought peace to the beings of the Sundarban;

every creature had a place, every want was met,

all needs were balanced, like the lines of a couplet.

With illustrations by Salman Toor. (Public library) [79 pages]

The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay (1918)

This is one of the stranger books I’ve ever read. I happened to see it on Project Gutenberg and downloaded it pretty much for the title alone, without knowing anything about it. It’s an obscure Australian children’s chapter book peopled largely by talking animals. Bill Barnacle (a human), Bunyip Bluegum (a koala bear) and Sam Sawnoff (a penguin) come into possession of a magical pudding by the name of Albert. Cut into the puddin’ as often as you like for servings of steak and kidney pudding and apple dumpling – or your choice from a limited range of other comforting savoury and sweet dishes – and he simply regenerates.

This is one of the stranger books I’ve ever read. I happened to see it on Project Gutenberg and downloaded it pretty much for the title alone, without knowing anything about it. It’s an obscure Australian children’s chapter book peopled largely by talking animals. Bill Barnacle (a human), Bunyip Bluegum (a koala bear) and Sam Sawnoff (a penguin) come into possession of a magical pudding by the name of Albert. Cut into the puddin’ as often as you like for servings of steak and kidney pudding and apple dumpling – or your choice from a limited range of other comforting savoury and sweet dishes – and he simply regenerates.

Naturally, others want to get their hands on this handy source of bounteous food, and the characters have to fend off would-be puddin’-snatchers such as a possum and a wombat and even take their case before a judge. The four chapters are called “Slices,” there are lots of songs reminiscent of Edward Lear, and the dialogue often veers into the farcical:

“‘You can’t wear hats that high, without there’s puddin’s under them,’ said Bill. ‘That’s not puddin’s,’ said the Possum; ‘that’s ventilation. He wears his hat like that to keep his brain cool.’”

I did find it all amusing, but also inane, such that I don’t necessarily think it earns its place as a rediscovered classic. It didn’t help that I then borrowed a copy of the book from the library and found that it was a terribly reproduced “Alpha Editions” version in Comic Sans with distorted illustrations and no line breaks in the songs. (Public library) [169 pages]

Tree Glee: How and Why Trees Make Us Feel Better by Cheryl Rickman (2022)

This is a small-format coffee table self-help book for nature lovers. It affirms something that many of us know intuitively: being around trees improves our mood and our health. Rickman looks at this from a psychological and a cultural perspective, and talks about her own love of trees and how it helped her get through difficult times in life such as when she lost her mum when she was a teenager. She includes some practical ideas for how to spend more time in nature and how we can fight to preserve trees. Unfortunately, a lot of the information was very familiar to me from books such as Rooted by Lyanda Lynn Haupt and Losing Eden by Lucy Jones – for a long time, forest bathing was one of the themes that kept recurring across my reading – such that this felt like an unnecessary rehashing, illustrated with stock photographs that are nice enough to look at but don’t add anything. [182 pages]

This is a small-format coffee table self-help book for nature lovers. It affirms something that many of us know intuitively: being around trees improves our mood and our health. Rickman looks at this from a psychological and a cultural perspective, and talks about her own love of trees and how it helped her get through difficult times in life such as when she lost her mum when she was a teenager. She includes some practical ideas for how to spend more time in nature and how we can fight to preserve trees. Unfortunately, a lot of the information was very familiar to me from books such as Rooted by Lyanda Lynn Haupt and Losing Eden by Lucy Jones – for a long time, forest bathing was one of the themes that kept recurring across my reading – such that this felt like an unnecessary rehashing, illustrated with stock photographs that are nice enough to look at but don’t add anything. [182 pages]

With thanks to Welbeck for the free copy for review.

Six Degrees of Separation: From The End of the Affair to Nutshell

This month we begin with The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, a perfect excuse for me to review a novel I finished more than a year ago. This was only my second novel from Greene, after The Quiet American many a year ago. It’s subtle: low on action and majoring on recollection and regret. Mostly what we get are the bitter memories of Maurice Bendrix, a writer who had an affair with his clueless friend Henry’s wife Sarah during the last days of the Second World War. After she broke up with him, he remained obsessed with her and hired Parkis, a lower-class private detective, to figure out why. To his surprise, Sarah’s diaries revealed, not that she’d taken up with another man, but that she’d found religion. Maurice finds himself in the odd position of being jealous of … God? (More thoughts here.)

This month we begin with The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, a perfect excuse for me to review a novel I finished more than a year ago. This was only my second novel from Greene, after The Quiet American many a year ago. It’s subtle: low on action and majoring on recollection and regret. Mostly what we get are the bitter memories of Maurice Bendrix, a writer who had an affair with his clueless friend Henry’s wife Sarah during the last days of the Second World War. After she broke up with him, he remained obsessed with her and hired Parkis, a lower-class private detective, to figure out why. To his surprise, Sarah’s diaries revealed, not that she’d taken up with another man, but that she’d found religion. Maurice finds himself in the odd position of being jealous of … God? (More thoughts here.)

#1 I asked myself if I’d ever read another book where someone was jealous of a concept rather than a fellow human being, and finally came up with one. I enjoyed Cooking as Fast as I Can by Cat Cora even though I wasn’t aware of this Food Network celebrity and restaurateur. Her memoir focuses on her Mississippi upbringing in a half-Greek adoptive family and the challenges of being gay in the South. Separate obsessions plagued her marriage; I remember at one point she gave her wife an ultimatum: it’s either me or the hot yoga.

#1 I asked myself if I’d ever read another book where someone was jealous of a concept rather than a fellow human being, and finally came up with one. I enjoyed Cooking as Fast as I Can by Cat Cora even though I wasn’t aware of this Food Network celebrity and restaurateur. Her memoir focuses on her Mississippi upbringing in a half-Greek adoptive family and the challenges of being gay in the South. Separate obsessions plagued her marriage; I remember at one point she gave her wife an ultimatum: it’s either me or the hot yoga.

#2 Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It by Geoff Dyer is one of my favourite-ever book titles. The title is his proposed idea for a self-help book, but … wait for the punchline … he couldn’t be bothered to write it. It’s a book of disparate travel essays, with him as the bumbling antihero, sluggish and stoned. This wasn’t one of his better books, but his descriptions and one-liners are always amusing (my review).

#2 Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It by Geoff Dyer is one of my favourite-ever book titles. The title is his proposed idea for a self-help book, but … wait for the punchline … he couldn’t be bothered to write it. It’s a book of disparate travel essays, with him as the bumbling antihero, sluggish and stoned. This wasn’t one of his better books, but his descriptions and one-liners are always amusing (my review).

#3 Another book with a fantastic title that has nothing to do with the contents: Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls by David Sedaris. Again, not my favourite of his essay collections (try Me Talk Pretty One Day or When You Are Engulfed in Flames instead), but he’s reliable for laughs.

#3 Another book with a fantastic title that has nothing to do with the contents: Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls by David Sedaris. Again, not my favourite of his essay collections (try Me Talk Pretty One Day or When You Are Engulfed in Flames instead), but he’s reliable for laughs.

#4 No more about owls than the previous one; Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame is an autobiographical novel that tells the same story as her An Angel at My Table trilogy (but less compellingly): a hardscrabble upbringing in New Zealand and mental illness that led to incarceration in psychiatric hospitals. The title phrase is from Ariel’s song in The Tempest, which the Withers siblings learn at school. I’ve been ‘reading’ this for nearly a year and a half; really, it’s mostly been on the set-aside shelf for that time.

#4 No more about owls than the previous one; Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame is an autobiographical novel that tells the same story as her An Angel at My Table trilogy (but less compellingly): a hardscrabble upbringing in New Zealand and mental illness that led to incarceration in psychiatric hospitals. The title phrase is from Ariel’s song in The Tempest, which the Withers siblings learn at school. I’ve been ‘reading’ this for nearly a year and a half; really, it’s mostly been on the set-aside shelf for that time.

#5 Another title drawn from Shakespeare: there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler is one of my Most Anticipated Books of 2022. It’s about a female friendship that links Brazil and London. I’m holding out hope for a review copy.

#5 Another title drawn from Shakespeare: there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler is one of my Most Anticipated Books of 2022. It’s about a female friendship that links Brazil and London. I’m holding out hope for a review copy.

#6 Fowler’s title comes from Hamlet, which provides the plot for Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, one of his strongest novels of recent years. Within a few pages, I was captivated and utterly convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this foetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his future depends on it.

#6 Fowler’s title comes from Hamlet, which provides the plot for Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, one of his strongest novels of recent years. Within a few pages, I was captivated and utterly convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this foetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his future depends on it.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages] After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”  House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)  36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)  God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.”

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.” Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.”

Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.” The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry grew up together in Chicago. Both are light-skinned African American women, their features described as “olive” or “golden.” Irene has remained within the Black community, marrying a doctor named Brian and living a comfortable life in Harlem. However, she is able to pass as white in certain circumstances, such as when she and Clare meet for tea in a high-end establishment. Clare, on the other hand, is hiding her ancestry from her white husband, Jack Bellew, who spews hatred for Black people. “It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do. If one’s the type, all that’s needed is a little nerve,” she insists.

Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry grew up together in Chicago. Both are light-skinned African American women, their features described as “olive” or “golden.” Irene has remained within the Black community, marrying a doctor named Brian and living a comfortable life in Harlem. However, she is able to pass as white in certain circumstances, such as when she and Clare meet for tea in a high-end establishment. Clare, on the other hand, is hiding her ancestry from her white husband, Jack Bellew, who spews hatred for Black people. “It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do. If one’s the type, all that’s needed is a little nerve,” she insists. I’d long wanted to read this and couldn’t find it through a library, so bought a copy as part of a Foyles order funded by last year’s Christmas money. I’m not clear on whether the Penguin Little Black Classics edition is abridged, but the 1929 preface by Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke’s correspondent, only mentions 10 letters, which is how many are printed here, so I have at least gotten the gist. Most of the letters were sent in 1903–4, with a final one dated 1908, from various locations on Rilke’s European travels.

I’d long wanted to read this and couldn’t find it through a library, so bought a copy as part of a Foyles order funded by last year’s Christmas money. I’m not clear on whether the Penguin Little Black Classics edition is abridged, but the 1929 preface by Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke’s correspondent, only mentions 10 letters, which is how many are printed here, so I have at least gotten the gist. Most of the letters were sent in 1903–4, with a final one dated 1908, from various locations on Rilke’s European travels.