What Lies Hidden: Secrets of the Sea House & Night Waking

When I read Kay’s review of Sarah Maine’s The House Between Tides, the book seemed so familiar I did a double take. A Scottish island in the Outer Hebrides … dual contemporary and historical story lines … the discovery of a skeleton. It sounded just like Night Waking by Sarah Moss (another Sarah M.!), which I was already planning on rereading on our trip to the Outer Hebrides. Kay then suggested a readalike that ended up being even more similar, Elisabeth Gifford’s The Sea House (U.S. title), one of whose plots was Victorian and the skeleton in which was a baby’s. I passed on the Maine but couldn’t resist finding a copy of the Gifford from the library so I could compare it with the Moss. Both:

Secrets of the Sea House by Elisabeth Gifford (2013)

Although nearly 130 years separate the two protagonists, they are linked by the specific setting – a manse on the island of Harris – and a belief that they are descended from selkies. In 1992, Ruth and her husband are converting the Sea House into a B&B and hoping to start a family. When they find the remains of a baby with skeletal deformities reminiscent of a mermaid under the floorboards, Ruth plunges into a search for the truth of what happened in their home. In 1860, Reverend Alexander Ferguson lived here and indulged his amateur naturalist curiosity about cetaceans and the dubious creatures announced as “mermaids” (often poor taxidermy crosses between a monkey and a fish, as in The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock).

Although nearly 130 years separate the two protagonists, they are linked by the specific setting – a manse on the island of Harris – and a belief that they are descended from selkies. In 1992, Ruth and her husband are converting the Sea House into a B&B and hoping to start a family. When they find the remains of a baby with skeletal deformities reminiscent of a mermaid under the floorboards, Ruth plunges into a search for the truth of what happened in their home. In 1860, Reverend Alexander Ferguson lived here and indulged his amateur naturalist curiosity about cetaceans and the dubious creatures announced as “mermaids” (often poor taxidermy crosses between a monkey and a fish, as in The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock).

Ruth and Alexander trade off as narrators, but we get a more rounded view of mid-19th-century life through additional chapters voiced by the reverend’s feisty maid, Moira, a Gaelic speaker whose backstory reveals the cruelty of the Clearances – she won’t forgive the laird for what happened to her family. Gifford’s rendering of period prose wasn’t altogether convincing and there are some melodramatic moments: this could be categorized under romance, and I was surprised by the focus on Ruth’s traumatic upbringing in a children’s home after her mother’s death by drowning. Still, this was an absorbing novel and I actually learned a lot, including the currently accepted explanation for where selkie myths come from.

I also was relieved that Gifford uses real place names instead of disguising them (as Bella Pollen and Sarah Moss did). We passed through the tiny town of Scarista, where the manse is meant to be, on our drive. If I’d known ahead of time that it was a real place, I would have been sure to stop for a photo op (it must be this B&B!). We also stopped in Tarbert, a frequent point of reference, to visit the Harris Gin distillery. (Public library)

Night Waking by Sarah Moss (2011)

This was my first of Moss’s books and I have always felt guilty that I didn’t appreciate it more. I found the voice more enjoyable this time, but was still frustrated by a couple of things. Dr Anna Bennet is a harried mum of two and an Oxford research fellow trying to finish her book (on Romantic visions of childhood versus the reality of residential institutions – a further link to the Gifford) while spending a summer with her family on the remote island of Colsay, which is similar to St. Kilda. Her husband, Giles Cassingham, inherited the island but is also there to monitor the puffin numbers and track the effects of climate change. Anna finds a baby’s skeleton in the garden while trying to plant some fruit trees. From now on, she’ll snatch every spare moment (and trace of Internet connection) away from her sons Raph and Moth – and the builders and the police – to write her book and research what might have happened on Colsay.

Each chapter opens with an epigraph from a classic work on childhood (e.g. by John Bowlby or Anna Freud). Anna also inserts excerpts from her manuscript in progress and fragments of texts she reads online. Adding to the epistolary setup is a series of letters dated 1878: May Moberley reports to her sister Allie and others on the conditions on Colsay, where she arrives to act as a nurse and address the island’s alarming infant mortality statistics. It took me the entire book to realize that Allie and May are the sisters from Moss’s 2014 novel Bodies of Light; I’m glad I didn’t remember, as there was a shock awaiting me.

Each chapter opens with an epigraph from a classic work on childhood (e.g. by John Bowlby or Anna Freud). Anna also inserts excerpts from her manuscript in progress and fragments of texts she reads online. Adding to the epistolary setup is a series of letters dated 1878: May Moberley reports to her sister Allie and others on the conditions on Colsay, where she arrives to act as a nurse and address the island’s alarming infant mortality statistics. It took me the entire book to realize that Allie and May are the sisters from Moss’s 2014 novel Bodies of Light; I’m glad I didn’t remember, as there was a shock awaiting me.

According to Goodreads, I first read this over just four days in early 2012. (This was back in the days where I read only one book at a time, or at most two, one fiction and one nonfiction.) I remember feeling like I should have enjoyed its combination of topics – puffin fieldwork, a small island, historical research – much more, but I was irked by the constant intrusions of the precocious children. That is, of course, the point: they interrupt Anna’s life, sleep and research, and she longs for a ‘room of her own’ where she can be a person of intellect again instead of wiping bottoms and assembling sometimes disgusting meals. She loves her children, but hates the daily drudgery of motherhood. Thankfully, there’s hope at the end that she’ll get what she desires.

I had completely forgotten the subplot about the first family they rent out the new holiday cottage to (yet another tie-in to the Gifford, in which they’re preparing to open a guest house): a hot mess of alcoholic mother, workaholic father, and university-age daughter with an eating disorder. Zoe’s interactions with the boys, and Anna’s role as makeshift counsellor to her, are sweet, but honestly? I would have cut this story line entirely. Really, I longed for the novella length and precision of a later work like Ghost Wall. Still, I was happy to reread this, with Anna’s wry wit a particular highlight, and to discover for the first time (silly me!) that thread of connection with Bodies of Light / Signs for Lost Children. (Free from a neighbour)

Original rating:

My rating now:

I enjoyed the Gifford enough to immediately request the library’s copy of one of her newer novels, The Lost Lights of St. Kilda, so my connection to the Western Isles can at least continue through my reading. I also found a pair of children’s novels plus a mystery novel set on St. Kilda, and I was sent an upcoming novel set on an island off the west coast of Scotland, so I’ll be on this Scotland reading kick for a while!

Truth Is Stranger than Fiction: The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen

“The island exerted a mesmeric pull. She had felt the magic of it all her life, but it was a magic that stayed on the island. You couldn’t take it with you.”

~MILD SPOILERS IN THIS ONE~

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

Now it’s just Letitia and the three children. Georgie is awaiting exam results and university offers. Jamie is the youngest and has an earnest, innocent, literal mind (I believe I first came across the novel in connection to my interest in depictions of autism, and I assume he is meant to be on the spectrum). Alba, smack in the middle, acts out via snarky comments as well as shoplifting and tormenting her brother. The locals look out for each of the family members and make allowances for the strange things they do because of grief.

In the meantime, there’s an escaped grizzly bear on the loose in the islands. The chapters rotate through the main characters’ perspectives and include short imaginings of the bear’s journey. I found it hard to take these seriously – could an animal really be in awe of the Northern Lights? – especially when Pollen begins to suggest telepathic communication occurring between Jamie and the bear.

I was a third of the way into the novel before I learned that the bear subplot was based on a true story – my husband saw a sidebar about it in the guidebook. I’d had no idea! Hercules the trained bear starred in films and commercials. In 1980, while filming an ad for Andrex, he slipped his rope and remained on the run for several weeks despite a military search, straying 20 miles and losing half his body weight before he was tranquillized and returned to his owner. We made the pilgrimage to his burial site in Langass Woodland.

Pollen herself spent childhood summers in the Outer Hebrides and remembered the buzz about the hunt for Hercules. This plus the recent death of their father makes it a pivotal summer for all three children. Though in general I appreciated the descriptions of the island, and liked the character interactions and Jamie’s guilelessness and gumption, I felt uncomfortable with his portrayal. I didn’t think it realistic for an 11-year-old to not understand the fact of death; it seemed almost offensive to suggest that, because he’s on the autism spectrum, he wouldn’t understand euphemisms about loss. The sequence where he goes looking for “Heaven” is pretty excruciating.

Add that to the unlikelihood of Jamie’s participation in the bear’s discovery and an unnecessary conspiracy element about Nicky’s death and this novel didn’t live up to its potential for me. I’d read one other book by Pollen, the memoir Meet Me in the In-Between, but won’t venture further into her work. Still, this was an interesting curio. (Public library)

[I thought about including this (and Sarah Moss’s Night Waking) in my flora-themed 20 Books of Summer because of the author’s surname, but I think I’ll make my 20 without stretching that far!]

Adventuring (and Reading) in the Outer Hebrides

Islands are irresistible for the unique identities they develop through isolation, and the extra effort that it often takes to reach them. Over the years, my husband and I have developed a special fondness for Britain’s islands – the smaller and more remote the better. After exploring the Inner Hebrides in 2005 and Orkney and Shetland in 2006, we always intended to see more of Scotland’s islands; why ever did we leave it this long?

Rail strikes and cancelled trains threatened our itinerary more than once, so it was a relief that we were able to go, even at extra cost. Our back-up plan left us with a spare day in Inverness, which we filled with coffee and pastries outside the cathedral, browsing at Leakey’s bookshop, walking along the River Ness and in the botanical gardens, and a meal overlooking the 19th-century castle.

Then it was on to the Outer Hebrides at last, via a bus ride and then a ferry to Stornoway in Lewis, the largest settlement in the Western Isles. Here we rented a car for a week to allow us to explore the islands at will. We were surprised at how major a town Stornoway is, with a big supermarket and slight suburban sprawl – yet it was dead on the Saturday morning we went in to walk around; not until 11:30 was there anything like the bustle we expected.

We’d booked three nights in a tiny Airbnb house 15 minutes from the capital. First up on our tourist agenda was Callanish stone circle, which we had to ourselves (once the German coach party left). Unlike at Stonehenge, you can walk in among the standing stones. The rest of our time on Lewis went to futile whale watching, the castle grounds, and beach walks.

This post threatens to become a boring rundown, so I’ll organize the rest thematically, introduced by songs by Scottish artists.

“I’ll Always Leave the Light On” by Kris Drever

Long days: The daylight lasts longer so far north, so each day we could plan activities not just for the morning and afternoon but late into the evening. At our second stop – three nights in another Airbnb on North Uist – we took walks after dinner, often not coming back until 10 p.m., at which point there was still another half-hour until sunset.

“Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” by Travis

Weather: We got a mixture of sun and clouds. It rained at least a bit on most days, and we got drenched twice, walking out to an eagle observatory on Harris (where we saw no eagles, as they are too sensible to fly in the rain) and dashing back to the car from a coastal excursion. I was doomed to wearing plastic bags around my feet inside my disintegrating hiking boots for the rest of the trip. There was also a strong wind much of the time, which made it feel colder than the temperature suggested – I often wore my fleece and winter hat.

A witty approach to weather forecasting. (Outside the shop/bistro on Berneray.)

“St Kilda Wren” by Julie Fowlis

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Wildlife: The Outer Hebrides is a bastion for some rare birds: the corncrake, the red-necked phalarope, and both golden and white-tailed eagles. Thanks to intel gleaned from Twitter, my husband easily found a phalarope swimming in a small roadside loch. Corncrakes hide so well they are virtually impossible to see, but you will surely hear their rasping calls from the long grass. Balranald is the westernmost RSPB reserve and a wonderful place to hear corncrakes and see seabirds flying above the machair (wildflower-rich coastal grassland). No golden eagles, but we did see a white-tailed eagle flying over our accommodation on our last day, and short-eared owls were seemingly a dime a dozen. We were worried we might see lots of dead birds on our trip due to the avian flu raging, but there were only five – four gannets and an eider – and a couple looked long dead. Still, it’s a distressing situation.

We also attended an RSPB guided walk to look for otters and did indeed spot one on a sea loch. It happened to be the Outer Hebrides Wildlife Festival week. Our guide was knowledgeable about the geography and history of the islands as well.

Badges make great, cheap souvenirs!

St. Kilda: This uninhabited island really takes hold of the imagination. It can still be visited, but only via a small boat through famously rough seas. We didn’t chance it this time. I might never get there, but I enjoy reading about it. There’s a viewing point on North Uist where one can see out to St. Kilda, but it was only the vaguest of outlines on the hazy day we stopped.

“Traiveller’s Joy” by Emily Smith

Additional highlights:

- An extended late afternoon tea at Mollans rainbow takeaway shed on Lewis. Many of the other eateries we’d eyed up in the guidebook were closed, either temporarily or for good – perhaps an effect of Covid, which hit just after the latest edition was published.

- A long reading session with a view by the Butt of Lewis, which has a Stevenson lighthouse.

- Watching mum and baby seals playing by the spit outside our B&B window on Berneray.

- Peat smoked salmon. As much of it as I could get.

- A G&T with Harris gin (made with kelp).

“Dear Prudence” (Beatles cover) by Lau

Surprises:

- Gorgeous, deserted beaches. This is Luskentyre on Harris.

- No midges to speak of. The Highlands are notorious for these biting insects, but the wind kept them away most of the time we were on the islands. We only noticed them in the air on one still evening, but they weren’t even bad enough to deploy the Avon Skin So Soft we borrowed from a neighbour.

- People still cut and burn peats for fuel. Indeed, when we stepped into the Harris gin distillery for a look around, I was so cold and wet that I warmed my hands by a peat fire! Even into the 1960s, people lived in primitive blackhouses, some of which have now been restored as holiday rentals. The one below is run as a museum.

- Not far outside Stornoway is the tiny town of Tong. We passed through it each day. Here Mary Anne MacLeod was born in 1912. If only she’d stayed on Lewis instead of emigrating to New York City, where she met Fred Trump and had, among other children, a son named Donald…

- Lord Leverhulme, founder of Unilever, bought Lewis in 1918 and part of Harris the next year. He tried to get crofters to work in his businesses, but all his plans met with resistance and his time there was a failure, as symbolized by this “bridge to nowhere” (Garry Bridge). His legacy is portrayed very differently here compared to in Port Sunlight, the factory workers’ town he set up in Merseyside.

- The most far-flung Little Free Library I’ve ever visited (on Lewis).

- Visits from Lulu the cat at our North Uist Airbnb.

“Wrapped Up in Books” by Belle and Sebastian

What I read: I aimed for lots of relevant on-location reads. I can’t claim Book Serendipity: reading multiple novels set on Scottish islands, it’s no surprise if isolation, the history of the Clearances, boat rides, selkies and seabirds recur. However, the coincidences were notable for one pair, Secrets of the Sea House by Elisabeth Gifford and Night Waking by Sarah Moss, a reread for me. I’ll review these two together, as well as The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen (inspired by a real incident that occurred on North Uist in 1980), in full later this week.

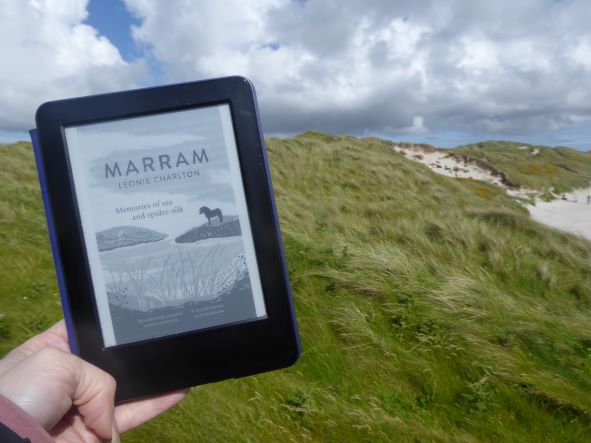

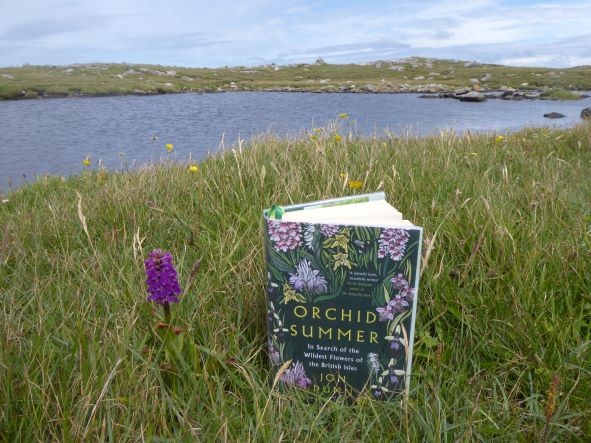

I also read about half of Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie, a reread for me; its essays on gannets and St. Kilda chimed with the rest of my reading. Marram, Leonie Charlton’s memoir of pony trekking through the Outer Hebrides, will form part of a later 20 Books of Summer post thanks to the flora connection, as will Jon Dunn’s Orchid Summer, one chapter of which involves a jaunt to North Uist to find a rare species.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

I also acquired four books on the trip: one from the Little Free Library and three from Inverness charity shops.

I started reading all three in the bottom pile, and read a few more books on my Kindle, two of them for upcoming paid reviews. The third was:

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

On my recommendation, my husband read Love of Country by Madeleine Bunting and The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, two excellent nonfiction books about Britain’s islands and coastline.

“Other Side of the World” by KT Tunstall

General impressions: We weren’t so taken with Lewis on the whole, but absolutely loved what we saw of Harris on our drive to the ferry to Berneray and wished we’d allotted it more time. While we only had one night on Berneray and mostly saw it in the rain, we thought it a lovely little place. It only has the one shop, which doubles as the bistro in the evenings – warned by the guidebook that this is the only place to eat on the island, we made our dinner reservation many weeks in advance. The following morning, as we ate our full Scottish cooked breakfast, I asked the B&B owner what led him to move from England to “the ends of the earth.” He took mild objection to my tossed-off remark and replied that the islands are more like “the heart of it all.” Thanks to fast Internet service, remote working is no issue.

We are more than half serious when we talk about moving to Scotland one day. We love Edinburgh, though the tourists might drive us mad, and enjoyed our time in Wigtown four years ago. I’d like to think we could even cope with island life in Orkney or the Hebrides. We imagine them having warm, tight-knit communities, but would newcomers feel welcome? With only one major supermarket in the whole Western Isles, would we find enough fresh fruit and veg? And however would one survive the bleakness of the winters?

North Uist captivated us right away, though. Within 15 minutes of driving onto the island via a causeway, we’d seen three short-eared owls and three red deer stags, and we got great views of hen harriers and other raptors. One evening we found ourselves under what seemed to be a raven highway. It felt unlike anywhere else we’d been: pleasingly empty of humans, and thus a wildlife haven.

The long journey home: The public transport nightmares of our return trip put something of a damper on the end of the holiday. We left the islands via a ferry to Skye, where we caught a bus. So far, so good. Our second bus, however, broke down in the middle of nowhere in the Highlands and the driver plus we five passengers were stuck for 3.5 hours awaiting a taxi we thought would never come. When it did, it drove the winding road at terrifying speed through the pitch black.

Grateful to be alive, we spent the following half-day in Edinburgh, bravely finding brunch, the botanic gardens and ice cream with our heavy luggage in tow. The final leg home, alas, was also disrupted when our overcrowded train to Reading was delayed and we missed the final connection to Newbury, necessitating another taxi – luckily, both were covered by the transport operators, and we’ll also reclaim for our tickets. Much as we believe in public transport and want to support it, this experience gave us pause. Getting to and around Spain by car was so much easier, and that trip ended up a lot cheaper, too. Ironic!

Guarding the bags in Edinburgh

“Take Me Back to the Islands” by Idlewild

Next time: On this occasion we only got as far south as Benbecula (which, pleasingly, is pronounced Ben-BECK-you-luh). In the future we’d think about starting at the southern tip and seeing Barra, Eriskay and South Uist before travelling up to Harris. We’ve heard that these all have their own personalities. Now, will we get back before many more years pass?

The Poet by Louisa Reid (Blog Tour Review)

The Poet lured me with the prospect of a novel in verse (Girl, Woman, Other and Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile are two others I would recommend) and the theme of a female poet caught up in a destructive relationship with her former professor. Emma Eliot published a poetry collection at age 21 before embarking on an abandoned PhD on Charlotte Mew. Tom Abbot, a charming Oxford don in his early forties, left his wife and daughters for her, but Emma has found that the housewife existence doesn’t suit her and longs to return to academia. Tom relies on Emma to boost his ego, play stepmum and help him with his publications, but scorns her working-class upbringing and can’t conceive of her having her own life and desires.

Tom’s students and ex-wife commiserate with Emma over his arrogance, but in the end it’s up to her whether she’ll break free. She tells her story of betrayal, gaslighting and the search for revenge in free verse that flows effortlessly. Sometimes her words are addressed to Tom:

Miles of misunderstanding waver

between us

Anything would be better than the stink

of your

superiority.

– and other times to the reader.

Give me the confidence of a mediocre white man

who thinks he has the right to

a woman’s work –

her words

and womb –

and everything else.

if the bed seems too big

then perhaps that is because I have shrunk

to fit the space,

or am lost in the wasteland of what was.

There are a few poetry in-jokes like that one, with Emma quoting Emily Dickinson and Tom likening her early work to Sylvia Plath’s. Usually this feels like reading fiction rather than poetry, though the occasional passage where alliteration and internal rhymes bloom remind you that Emma is meant to be an accomplished poet.

I wanted to sit in a book-lined room

wombed in words.

I didn’t see the tomb that waited

for the woman

who underrated herself.

That said, I didn’t particularly rate this qua poetry, and the storytelling style wasn’t really enough to make a rather thin story stand out. Still, I’d recommend it to poetry-phobes, as well as to readers of The Wife by Meg Wolitzer and especially Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan (who, like Reid, wrote YA fiction before producing an adult novel in verse).

My thanks to Doubleday and Anne Cater of Random Things Tours for my proof copy for review.

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Poet. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

20 Books of Summer, 1–3: Hargrave, Powles & Stewart

Plants mirror minds,

Healing, harming powers

Growing green thoughts.

(First stanza of “Plants Mirror Minds” from The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws)

Here are my first three selections for my flora-themed summer reading. I hope to get through more of my own books, as opposed to library books and review copies, as the months go on. Today I have one of each from fiction, nonfiction and poetry, with the settings ranging from 16th-century Alsace to late-20th-century Spain.

The Dance Tree by Kiran Millwood Hargrave (2022)

Kiran Millwood Hargrave is one of my favourite new voices in historical fiction (she had written fiction for children and young adults before 2020’s The Mercies). Both novels hit the absolute sweet spot between the literary and women’s fiction camps, choosing a lesser-known time period and incident and filling in the background with sumptuous detail and language. Both also consider situations in which women, queer people and other cultural minorities were oppressed, and imagine characters pushing against those boundaries in affirming but authentic-feeling ways.

Kiran Millwood Hargrave is one of my favourite new voices in historical fiction (she had written fiction for children and young adults before 2020’s The Mercies). Both novels hit the absolute sweet spot between the literary and women’s fiction camps, choosing a lesser-known time period and incident and filling in the background with sumptuous detail and language. Both also consider situations in which women, queer people and other cultural minorities were oppressed, and imagine characters pushing against those boundaries in affirming but authentic-feeling ways.

The setting is Strasbourg in the sweltering summer of 1518, when a dancing plague (choreomania) hit and hundreds of women engaged in frenzied public dancing, often until their feet bled or even, allegedly, until 15 per day dropped dead. Lisbet observes this all at close hand through her sister-in-law and best friend, who get caught up in the dancing. In the final trimester of pregnancy at last after the loss of many pregnancies and babies, Lisbet tends to the family beekeeping enterprise while her husband is away, but gets distracted when two musicians (brought in to accompany the dancers; an early strategy before the council cracked down), one a Turk, lodge with her and her mother-in-law. The dance tree, where she commemorates her lost children, is her refuge away from the chaos enveloping the city. She’s a naive point-of-view character who quickly has her eyes opened about different ways of living. “It takes courage, to love beyond what others deem the right boundaries.”

This is likely to attract readers of Hamnet; I was also reminded of The Sleeping Beauties, in that the author’s note discusses the possibility that the dancing plagues were an example of a mass hysteria that arose in response to religious restrictions. (Public library)

Magnolia by Nina Mingya Powles (2020)

(Powles also kicked off my 2020 food-themed summer reading.) This came out from Nine Arches Press and a small New Zealand press two years ago but is being published in the USA by Tin House in August. I’ve reviewed it for Shelf Awareness in advance of that release. Those who are new to Powles’s work should enjoy her trademark blend of themes in this poetry collection. She’s mixed race and writes about crossing cultural and language boundaries – especially trying to express herself in Chinese and Hakka. Often, food is her way of embodying split loyalties and love for her heritage. I noted the alliteration in “Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly opening under swirls of soy sauce.” Magnolia is the literal translation of “Mulan,” and that Disney movie and a few other films play a major role here, as do writers Eileen Chang and Robin Hyde. My issue with the book is that it doesn’t feel sufficiently different from her essay collections that I’ve read – the other is Small Bodies of Water – especially given that many of the poems are in prose paragraphs. [Update: I dug out my copy of Small Bodies of Water from a box and found that, indeed, one piece had felt awfully familiar for a reason: that book contains a revised version of “Falling City” (about Eileen Chang’s Shanghai apartment), which first appeared here.] (Read via Edelweiss)

(Powles also kicked off my 2020 food-themed summer reading.) This came out from Nine Arches Press and a small New Zealand press two years ago but is being published in the USA by Tin House in August. I’ve reviewed it for Shelf Awareness in advance of that release. Those who are new to Powles’s work should enjoy her trademark blend of themes in this poetry collection. She’s mixed race and writes about crossing cultural and language boundaries – especially trying to express herself in Chinese and Hakka. Often, food is her way of embodying split loyalties and love for her heritage. I noted the alliteration in “Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly opening under swirls of soy sauce.” Magnolia is the literal translation of “Mulan,” and that Disney movie and a few other films play a major role here, as do writers Eileen Chang and Robin Hyde. My issue with the book is that it doesn’t feel sufficiently different from her essay collections that I’ve read – the other is Small Bodies of Water – especially given that many of the poems are in prose paragraphs. [Update: I dug out my copy of Small Bodies of Water from a box and found that, indeed, one piece had felt awfully familiar for a reason: that book contains a revised version of “Falling City” (about Eileen Chang’s Shanghai apartment), which first appeared here.] (Read via Edelweiss)

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree by Chris Stewart (2002)

It’s at least 10 years ago, probably nearer 15, that I read Driving over Lemons, the first in Stewart’s eventual trilogy about buying a remote farm in Andalusia. His books are in the Peter Mayle vein, low-key and humorous: an Englishman finds the good life abroad and tells amusing anecdotes about the locals and his own mishaps.

It’s at least 10 years ago, probably nearer 15, that I read Driving over Lemons, the first in Stewart’s eventual trilogy about buying a remote farm in Andalusia. His books are in the Peter Mayle vein, low-key and humorous: an Englishman finds the good life abroad and tells amusing anecdotes about the locals and his own mishaps.

This sequel stood out for me a little more than the previous book, if only because I mostly read it in Spain. It’s in discrete essays, some of which look back on his earlier life. He was a founding member of Genesis and very briefly the band’s drummer; and to make some cash for the farm he used to rent himself out as a sheep shearer, including during winters in Sweden.

To start with, they were really very isolated, such that getting a telephone line put in revolutionized their lives. By this time, his first book had become something of a literary sensation, so he reflects on its composition and early reception, remembering when the Mail sent a clueless reporter out to find him. Spanish bureaucracy becomes a key element, especially when it looks like their land might be flooded by the building of a dam. Despite that vague sense of dread, this was good fun. (Public library)

10 Days in Spain (or at Sea) and What I Read

(Susan is the queen of the holiday travel and reading post – see her latest here.)

We spent the end of May in Northern Spain, with 20+-hour ferry rides across the English Channel either way. Thank you for your good thoughts – we were lucky to have completely flat crossings, and the acupressure bracelets that I wore seemed to do the job, such that not only did I not feel sick, but I even had an appetite for a meal in the ship’s café each day.

Not a bad day to be at sea. (All photos in this post are by Chris Foster.)

With no preconceived ideas of what the area would be like and zero time to plan, we went with the flow and decided on hikes each morning based on the weather. After a chilly, rainy start, we had warm but not uncomfortable temperatures by the end of the week. My mental picture of Spain was of hot beaches, but the Atlantic climate of the north is more like that of Britain’s. Green gorse-covered, livestock-grazed hills reminded us of parts of Wales. Where we stayed near Potes (reached by a narrow road through a gorge) was on the edge of Picos de Europa national park. The mountain villages and wildflower-rich meadows we passed on walks were reminiscent of places we’ve been in Italy or the Swiss and Austrian Alps.

The flora and fauna were an intriguing mix of the familiar (like blackbirds and blue tits) and the exotic (black kites, Egyptian vultures; some different butterflies; evidence of brown bears, wolves and wild boar, though no actual sightings, of course). One special thing we did was visit Wild Finca, a regenerative farming project by a young English couple; we’d learned about it from their short film shown at New Networks for Nature last year. We’d noted that the towns have a lot of derelicts and properties for sale, which is rather sad to see. They told us farm abandonment is common: those who inherit a family farm and livestock might just leave the animals on the hills and move to a city apartment to have modern conveniences.

I was especially taken by this graffiti-covered derelict restaurant and accommodation complex. As I explored it I was reminded of Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment. It’s a wonder no one has tried to make this a roadside eatery again; it has a fantastic view!

It so happens that we were there for the traditional weekend when cattle are moved to new pastures. A cacophony of cowbells alerted us to herds going past our cottage window a couple of times, and once we were stopped on the road to let a small group through. We enjoyed trying local cheese and cider and had two restaurant meals, one at a trendy place in Potes and one at a roadside diner where we tried the regional speciality fabada, a creamy bean stew with sausage chunks.

Sampling local products and reading The Murderer’s Ape.

With our meager Spanish we just about got by. I used a phrase book so old it still referred to pesetas to figure out how to ask for roundtrip tickets, while my husband had learned a few useful restaurant-going phrases from the Duolingo language-learning app. For communicating with the cottage owner, though, we had to resort to Google Translate.

A highlight of our trip was the Fuente Dé cable car to 1900 meters / ~6200 feet above sea level, where we found snowbanks, Alpine choughs, and trumpet gentians. That was a popular spot, but on most of our other walks we didn’t see another human soul. We felt we’d found the real, hidden Spain, with a new and fascinating landscape around every corner. We didn’t make it to any prehistoric caves, alas – we would probably have had to book that well in advance – but otherwise experienced a lot of the highlights of the area.

On our way back to Santander for the ferry, we stopped in two famous towns: Comillas, known for its modernist architecture and a palace designed by Gaudí; and Santillana del Mar, which Jean-Paul Sartre once called the most beautiful town in Spain. We did not manage any city visits – Barcelona was too far and there was no train service; that will have to be for another trip. It was a very low-key, wildlife-filled and relaxing time, just what we needed before plunging back into work and DIY.

Santillana del Mar

What I Read

On the journey there and in the early part of the trip:

The Murderer’s Ape by Jakob Wegelius (translated from the Swedish by Peter Graves): Sally Jones is a ship’s engineer who journeys from Portugal to India to clear her captain’s name when he is accused of murder. She’s also a gorilla. Though she can’t speak, she understands human language and communicates via gestures and simple written words. This was the perfect rip-roaring adventure story to read at sea; the twisty plot and larger-than-life characters who aid or betray Sally Jones kept the nearly 600 pages turning quickly. I especially loved her time repairing accordions with an instrument maker. This is set in the 1920s or 30s, I suppose, with early airplanes and maharajahs, but still long-distance sea voyages. Published by Pushkin Children’s, it’s technically a teen novel and the middle book in a trilogy, but neither fact bothered me at all.

The Murderer’s Ape by Jakob Wegelius (translated from the Swedish by Peter Graves): Sally Jones is a ship’s engineer who journeys from Portugal to India to clear her captain’s name when he is accused of murder. She’s also a gorilla. Though she can’t speak, she understands human language and communicates via gestures and simple written words. This was the perfect rip-roaring adventure story to read at sea; the twisty plot and larger-than-life characters who aid or betray Sally Jones kept the nearly 600 pages turning quickly. I especially loved her time repairing accordions with an instrument maker. This is set in the 1920s or 30s, I suppose, with early airplanes and maharajahs, but still long-distance sea voyages. Published by Pushkin Children’s, it’s technically a teen novel and the middle book in a trilogy, but neither fact bothered me at all.

& to see me through the rest of the week:

The Feast by Margaret Kennedy: Originally published in 1950, this was reissued by Faber in 2021 with a foreword by Cathy Rentzenbrink – had she not made much of it, I’m not sure how well I would have recognized the allegorical framework of the Seven Deadly Sins. In August 1947, we learn, a Cornish hotel was buried under a fallen cliff, and with it seven people. Kennedy rewinds a month to let us watch the guests arriving, and to plumb their interactions and private thoughts. We have everyone from a Lady to a lady’s maid; I particularly liked the neglected Cove children. It took me until the very end to work out precisely who died and which sin each one represented. The characters and dialogue glisten. This is intelligent, literary yet light, and so makes great vacation/beach reading.

Book of Days by Phoebe Power: A set of autobiographical poems about walking the Camino pilgrimage route. Power writes about the rigours of the road – what she carried in her pack; finding places to stay and food to eat – but also gives tender pen portraits of her fellow walkers, who have come from many countries and for a variety of reasons: to escape an empty nest, to make amends, to remember a departed lover. Whether the pilgrim is religious or not, the Camino seems like a compulsion. Often the text feels more like narrative prose, though there are some sections laid out in stanzas or forming shapes on the page to remind you it is verse. I think what I mean to say is, it doesn’t feel that it was essential for this to be poetry. Short vignettes in a diary may have been more to my taste.

Book of Days by Phoebe Power: A set of autobiographical poems about walking the Camino pilgrimage route. Power writes about the rigours of the road – what she carried in her pack; finding places to stay and food to eat – but also gives tender pen portraits of her fellow walkers, who have come from many countries and for a variety of reasons: to escape an empty nest, to make amends, to remember a departed lover. Whether the pilgrim is religious or not, the Camino seems like a compulsion. Often the text feels more like narrative prose, though there are some sections laid out in stanzas or forming shapes on the page to remind you it is verse. I think what I mean to say is, it doesn’t feel that it was essential for this to be poetry. Short vignettes in a diary may have been more to my taste.

Two favourite passages:

into cobbled elegance; it’s opening time for shops

selling vegetables and pan and gratefully I present my

Spanish and warmth so far collected, and receive in return

smiles, interest, tomatoes, cheese.

We are resolute, though unknowing

if we will succeed at this.

We are still children here –

arriving, not yet grown

up.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

I’d also downloaded from Edelweiss the recent travel memoir The Way of the Wild Goose by Beebe Bahrami, in which she walks sections of the Camino in France and Spain and reflects on why the path keeps drawing her back. It’s been a probing, beautiful read so far – I think this is the mild, generically spiritual quest feel Jini Reddy was trying to achieve with Wanderland.

I’d also downloaded from Edelweiss the recent travel memoir The Way of the Wild Goose by Beebe Bahrami, in which she walks sections of the Camino in France and Spain and reflects on why the path keeps drawing her back. It’s been a probing, beautiful read so far – I think this is the mild, generically spiritual quest feel Jini Reddy was trying to achieve with Wanderland.

Plus, I read a few e-books for paid reviews and parts of other library books, including a trio of Spain-appropriate memoirs: As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee, Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, and A Parrot in the Pepper Tree by Chris Stewart – more about this last one in my first 20 Books of Summer post, coming up on Sunday.

Our next holiday, to the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, is just two weeks away! It’ll be very different, but no doubt equally welcome and book-stuffed.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die. This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed

This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on

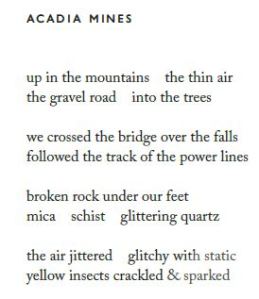

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on  Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

Burnet, Cumulus and Moss are “Hidden Folk” (like Iceland’s elves), ancient, tiny beings who hibernate for winter in an ash tree. When they lose their home and Cumulus, the oldest, starts fading away, they set off on a journey to look for more of their kind and figure out what is happening. This eventually takes them to “the Hive” (London, presumably); they are helped along the way by creatures they might have been wary of: they hitch rides on deer and pigeons, and a starling, fox and rat are their allies in the city.

Burnet, Cumulus and Moss are “Hidden Folk” (like Iceland’s elves), ancient, tiny beings who hibernate for winter in an ash tree. When they lose their home and Cumulus, the oldest, starts fading away, they set off on a journey to look for more of their kind and figure out what is happening. This eventually takes them to “the Hive” (London, presumably); they are helped along the way by creatures they might have been wary of: they hitch rides on deer and pigeons, and a starling, fox and rat are their allies in the city. A single-species monograph, this was more academic than I expected from Little Toller – it has statistics, tables and figures. So, it contains everything you ever wanted to know about ash trees, and then some. I actually bought it for my husband, who has found the late Rackham’s research on British landscapes useful, but thought I’d take a look as well. (The rental house we recently left had a self-seeded ash in the front garden that sprang up to almost the height of the house within the five years we lived there. Every time our landlords came round, we held our breath waiting for them to notice that the roots had started to push up the pavement and tell us it had to be cut down, but until now it has survived.)

A single-species monograph, this was more academic than I expected from Little Toller – it has statistics, tables and figures. So, it contains everything you ever wanted to know about ash trees, and then some. I actually bought it for my husband, who has found the late Rackham’s research on British landscapes useful, but thought I’d take a look as well. (The rental house we recently left had a self-seeded ash in the front garden that sprang up to almost the height of the house within the five years we lived there. Every time our landlords came round, we held our breath waiting for them to notice that the roots had started to push up the pavement and tell us it had to be cut down, but until now it has survived.)