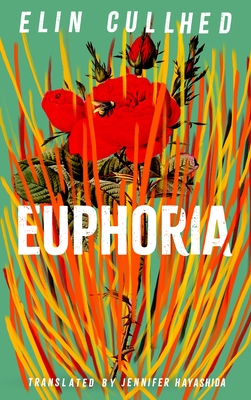

Literary Wives Club: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (2021)

Swedish author Elin Cullhed won the August Prize and was a finalist for the Strega European Prize with this first novel for adults. Euphoria is a recreation of Sylvia Plath’s state of mind in the last year of her life. It opens on 7 December 1962 in Devon with a list headed “7 REASONS NOT TO DIE,” most of which centre on her children, Frieda and Nick. She enumerates the pleasures of being in a physical body and enjoying coastal scenery. But she also doesn’t want to give her husband, poet Ted Hughes, the satisfaction of having his prophecies about her mental illness come true.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Cullhed seems to hew to biographical detail, though I’m not particularly familiar with the Hughes–Plath marriage. Scenes of their interactions with neighbours, Plath’s mother, and Ted’s lover Assia Wevill make their dynamic clear. The prose grows more nonstandard; run-on sentences and all-caps phrases indicate increasing mania. There are also lovely passages that seem apt for a poet: “Ted’s crystalline sly little mint lozenge eyes. Narrow foxish. Thin hard. His eyes, so embittered.” The use of language is effective at revealing Plath’s maternal ambivalence and shaky mental health. Somehow, though, I found this quite tedious by the end. Not among my favourite biographical novels, but surely a must-read for Plath fans. ![]()

Translated from the Swedish by Jennifer Hayashida in 2022 – our first read in translation, I think? And what a brilliant cover.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Marriage is claustrophobic here, as in so many of the books we read. Much as she loves her children, Plath finds the whole wifehood–motherhood complex to be oppressive and in direct conflict with her ambitions as an author. Sharing a vocation with her husband, far from helping him understand her, only makes her more bitter that he gets the time and exposure she so longs for. More than 60 years later, Plath’s death still echoes, a tragic loss to literature.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in March: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus – I’ve read this before but will plan to skim back through a copy from the library.

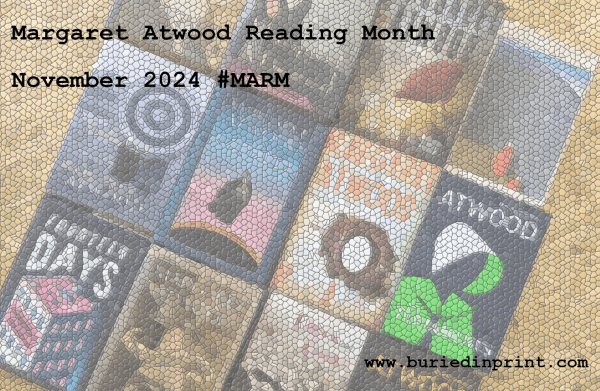

#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

Interlunar (1984)

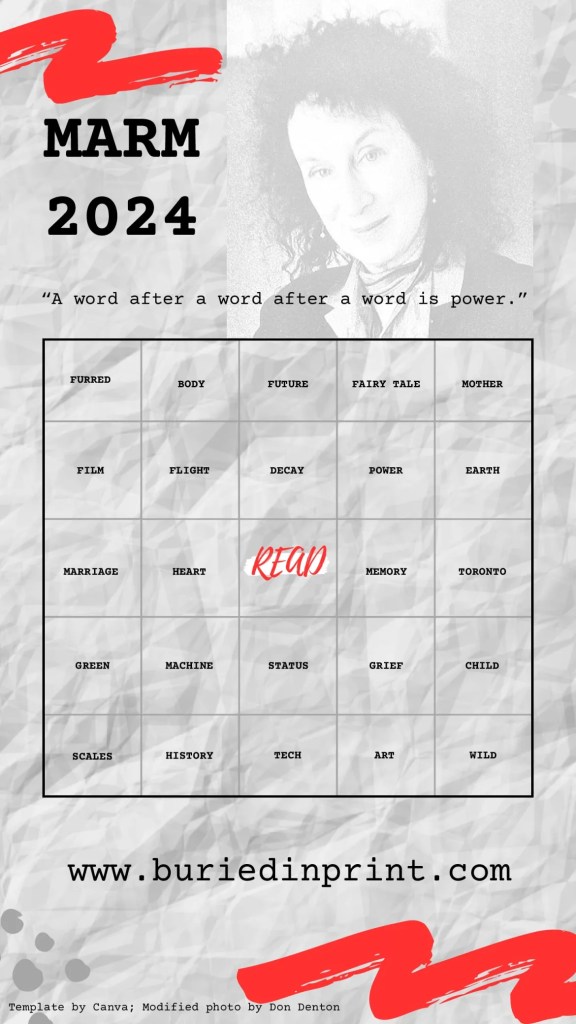

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

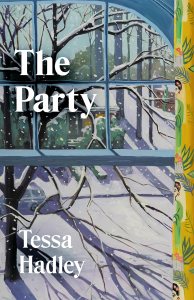

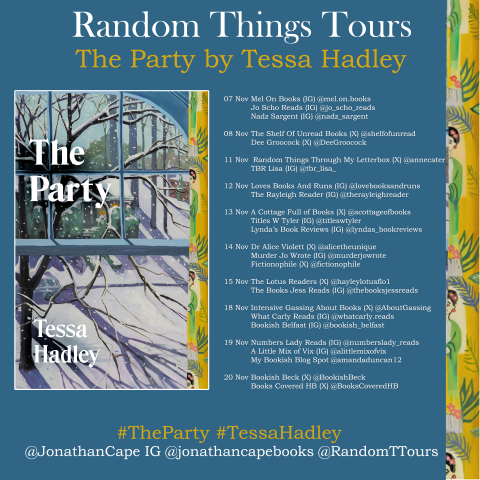

The Party by Tessa Hadley (Blog Tour and #NovNov24)

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

The novella’s three chapters each revolve around a party. First is the Bristol dockside pub party (published as a short story in the New Yorker); second is a cocktail party the girls’ parents are preparing for, giving us a window onto their troubled marriage; finally is a gathering Paul invites them to at the shabby inherited mansion he lives in with his cousin, invalid brother, and louche sister. “We camp in it like kids,” Paul says. “Just playing at being grown up, you know.” During their night spent at the mansion, the sisters become painfully aware of the class difference between them and Paul’s moneyed family. The divide between innocence and experience may be sharp, but the line between love and hatred is not always as clear as they expected. And from moments of decision all the rest of life flows.

In her novels and story collections, Hadley often writes about strained families, young women on the edge, and the way sex can force a change in direction. This was my eighth time reading her, and though The Party is as stylish as all her work, it didn’t particularly stand out for me, lacking the depth of her novels and the concentration of her stories. Still, it would be a good introduction to Hadley or, if you’re an established fan like me, you could read it in a sitting and be reminded of her sharp eye for manners and pretensions – and the emotions they mask.

[115 pages]

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Party from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Party. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth: Knulp by Hermann Hesse (1915)

My second contribution to German Literature Month (hosted by Lizzy Siddal) after A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai. This was my first time reading the German-Swiss Nobel Prize winner Hermann Hesse (1877–1962). I had heard of his novels Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, of course, but didn’t know about any of his shorter works before I picked this up from the Little Free Library last month. Knulp is a novella in three stories that provide complementary angles on the title character, a carefree vagabond whose rambling years are coming to an end.

“Early Spring” has a first-person plural narrator, opening “Once, early in the nineties, our friend Knulp had to go to hospital for several weeks.” Upon his discharge he stays with an old friend, the tanner Rothfuss, and spends his time visiting other local tradespeople and casually courting a servant girl. Knulp is a troubadour, writing poems and songs. Without career, family, or home, he lives in childlike simplicity.

He had seldom been arrested and never convicted of theft or mendicancy, and he had highly respected friends everywhere. Consequently, he was indulged by the authorities very much, as a nice-looking cat is indulged in a household, and left free to carry on an untroubled, elegant, splendidly aristocratic and idle existence.

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

In “The End,” Knulp encounters another school friend, Dr. Machold, who insists on sheltering the wayfarer. They’re in their forties but Knulp seems much older because he is ill with tuberculosis. As winter draws in, he resists returning to the hospital, wanting to die as he lived, on his own terms. The book closes with an extraordinary passage in which Knulp converses with God – or his hallucination of such – expressing his regret that he never made more of his talents or had a family. ‘God’ speaks these beautiful words of reassurance:

Look, I wanted you the way you are and no different. You were a wanderer in my name and wherever you went you brought the settled folk a little homesickness for freedom. In my name, you did silly things and people scoffed at you; I myself was scoffed at in you and loved in you. You are my child and my brother and a part of me. There is nothing you have enjoyed and suffered that I have not enjoyed and suffered with you.

I struggle with episodic fiction but have a lot of time for the theme of spiritual questioning. The seasons advance across the stories so that Knulp’s course mirrors the year’s. Knulp could almost be a rehearsal for Stoner: a spare story of the life and death of an Everyman. That I didn’t appreciate it more I put down to the piecemeal nature of the narrative and an unpleasant conversation between Knulp and Machold about adolescent sexual experiences – as in the attempted gang rape scene in Cider with Rosie, it’s presented as boyish fun when part of what Knulp recalls is actually molestation by an older girl cousin. I might be willing to try something else by Hesse. Do give me recommendations! (Little Free Library) ![]()

Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim.

[125 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Ramblin’ Man” by Lemon Jelly

- “I’ve Been Everywhere” by Johnny Cash

- “Rambling Man” by Laura Marling

- “Ballad of a Broken Man” by Duke Special

- “Railroad Man” by Eels

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

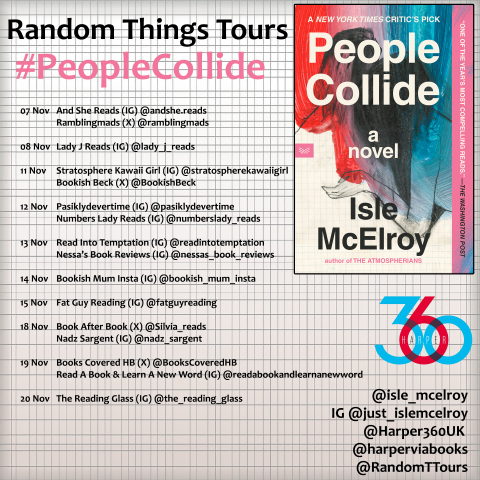

People Collide by Isle McElroy (Blog Tour)

People Collide (2023), nonbinary author Isle McElroy’s second novel, is a body swap story that explores the experiences and gender expectations of a heterosexual couple when they switch places. It’s not so much magic realism as a what-if experiment. Eli wakes up one morning in his wife Elizabeth’s body in their “pie slice of an apartment” in southern Bulgaria, where they moved for her government-sponsored teaching position. At first, finding himself alone, he thinks she’s disappeared and goes to the school to ask after her. The staff and students there, seeing him as Elizabeth, think they’re witnessing some kind of mental breakdown and send ‘her’ home. One of them is gone, yes, but it’s Elizabeth – in Eli’s body.

Both sets of parents get involved in the missing person case and, when a credit card purchase indicates Elizabeth is in Paris, Eli sets off after her. He is an apt narrator because he sees himself as malleable and inessential: “I wasn’t a person but a protean blob, intellectually and emotionally gelatinous, shaped by whatever surrounded me; “I could never shake the sense that I was, for [Elizabeth], like a supplementary arm grafted onto the center of her stomach.” He comes from a rough family background, has a history of disordered eating, and doesn’t have a career, so is mildly resentful of Elizabeth’s. She’s also an aspiring novelist and her solitary work takes priority while he cooks the meals and grades her students’ papers.

The couple already pushed against gender stereotypes, then, but it is still a revelation to Elizabeth how differently she is treated as a male. “I can’t name a single thing I don’t like about it. Everything’s become so much easier for me in your body,” she says to Eli when they finally meet up in Paris. There follows an arresting seven-page sex scene as they experience a familiar act anew in their partner’s body. “All that had changed was perspective.” But interactions with the partner’s parents assume primacy in much of the rest of the book.

This novel has an intriguing premise that offered a lot of potential, but it doesn’t really go anywhere with it. The sex scene actually struck me as the most interesting part, showing how being in a different body would help one understand desire. Beyond that, it feels like a stale rumination on passing as female (Elizabeth schooling Eli about menstruation and how to respond to her parents’ news about extended family) and women not being taken seriously in the arts (a lecture by a Rachel Cusk-like writer in the final chapter). I also couldn’t account for two unusual authorial decisions: Eli is caught up in a Parisian terrorist attack, but nothing results. Was it to shake things up at the one-third point, for want of a better idea? I also questioned the late shift to Elizabeth’s mother’s narration. Introducing a new first-person narrator, especially so close to the end, feels like cheating, or admitting defeat if there’s something important that Eli can’t witness. The author is skilled at creating backstory and getting characters from here to there. But in figuring out how the central incident would play out, the narrative falls short. Ultimately, I would have preferred this at short story length, where suggestion would be enough and more could have been left to the imagination.

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and HarperVia for the free copy for review.

Buy People Collide from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for People Collide. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

Orbital by Samantha Harvey (#NovNov24 Buddy Read)

Orbital is a circadian narrative, but its one day contains multitudes. Every 90 minutes, a spacecraft completes an orbit of the Earth; the 24 hours the astronauts experience equate to 16 days. And in the same way, this Booker Prize-shortlisted novella contains much more than seems possible for its page length. It plays with scale, zooming from the cosmic down to the human, then back. The situation is simultaneously extraordinary and routine:

Six of them in a great H of metal hanging above the earth. They turn head on heel, four astronauts (American, Japanese, British, Italian) and two cosmonauts (Russian, Russian); two women, four men, one space station made up of seventeen connecting modules, seventeen and a half thousand miles an hour. They are the latest six of many, nothing unusual about this any more[.]

We see these characters – Anton, Roman, Nell, Chie, Shaun, and Pietro – going about daily life as they approach the moon: taking readings, recording data on their health and lab mice’s, exercising, conversing over packaged foods, watching a film, then getting back into the sleeping bags where they started the day. Apart from occasional messages from family, theirs is a completely separate, closed-off existence. Is it magical or claustrophobic? Godlike, they cast benevolent eyes over a whole planet, yet their thoughts are always with the two or three individual humans who mean most to them. A wife, a daughter, a mother who has just died.

Apart from the bereaved astronaut – the one I sympathized with most – I didn’t get a strong sense of the characters as individuals. This may have been deliberate on Harvey’s part, to emphasize how reliant the six are on each other for survival: “we are one. Everything we have up here is only what we reuse and share. … We drink each other’s recycled urine. We breathe each other’s recycled air.” That collectivity and the overt messaging give the book the air of a parable.

Maybe it’s hard to shift from thinking your planet is safe at the centre of it all to knowing in fact it’s a planet of normalish size and normalish mass rotating about an average star in a solar system of average everything in a galaxy of innumerably many, and that the whole thing is going to explode or collapse.

Our lives here are inexpressibly trivial and momentous at once … Both repetitive and unprecedented. We matter greatly and not at all.

Gaining perspective on humankind is always valuable. There is also a strong environmental warning here. “The planet is shaped by the sheer amazing force of human want, which has changed everything, the forests, the poles, the reservoirs, the glaciers, the rivers, the seas, the mountains, the coastlines, the skies”. The astronauts observe climate breakdown firsthand through the inexorable development of a super-typhoon over the Philippines.

There are some stunning lyrical passages (“We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being … This summery burst of life is more bomb than bud. These fecund times are moving fast”), but Harvey sometimes gets carried away with the sound of words or the sweep of imagery, such that the style threatens to overwhelm the import. This was especially true of the last line. At times, I felt I was watching a BBC nature documentary full of soaring panoramas and time-lapse shots, all choreographed to an ethereal Sigur Rós soundtrack. Am I a cynic for saying so? I confess I don’t think this will win the Booker. But for the most part, I was entranced; grateful for the peek at the immensity of space, the wonder of Earth, and the fragility of human beings. (Public library)

[136 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Space Walk” by Lemon Jelly

- “Spacewalk” by Bell X1

- “Magic” & “Wonder” by Gungor

- “Hoppípolla” by Sigur Rós

- “Little Astronaut” by Jim Molyneux and Spell Songs

Never fear, others have been more enthusiastic!

Reviewed for this challenge so far by:

A Bag Full of Stories (Susana)

Book Chatter (Tina)

Books Are My Favourite and Best (Kate)

Buried in Print (Marcie)

Calmgrove (Chris)

The Intrepid Angeleno (Jinjer)

My Head Is Full of Books (Anne)

Words and Peace (Emma)

Reviewed earlier by other participants and friends:

#SciFiMonth: A Simple Intervention (#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth) & Station Eleven Reread

It’s rare for me to pick up a work of science fiction but occasionally I’ll find a book that hits the sweet spot between literary fiction and sci-fi. Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell are a few prime examples. It was the comparisons to Margaret Atwood and Kazuo Ishiguro, masters of the speculative, that drew me to my first selection, a Peirene Press novella. My second was a reread, 10 years on, for book club, whose postapocalyptic content felt strangely appropriate for a week that delivered cataclysmic election results.

A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai (2022; 2024)

[Translated from the German by Marielle Sutherland]

Meret is a nurse on a surgical ward, content in the knowledge that she’s making a difference. Her hospital offers a pioneering procedure that cures people of mental illnesses. It’s painless and takes just an hour.

The doctor had to find the affected area and put it to sleep, like a sick animal. That was his job. Mine was to keep the patients occupied. I was to distract them from what was happening and keep them interacting with me. As long as they stayed awake, we knew the doctor and his instruments had found the right place.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

Inokai invites us to ponder whether what we perceive as defects are actually valuable personality traits. More examples of interventions and their aftermath would be a useful point of comparison, though, and the pace is uneven, with a lot of unnecessary-seeming backstory about Meret’s family life. In the letter that accompanied my review copy, Inokai explained her three aims: to portray a nurse (her mother’s career) because they’re underrepresented in fiction, “to explore our yearning to cut out our ‘demons’,” and to offer “a queer love story that was hopeful.” She certainly succeeds with those first and third goals, but with the central subject I felt she faltered through vagueness.

Born in Switzerland, Inokai now lives in Berlin. This also counts as my first contribution to German Literature Month; another is on the way!

[187 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

For synopsis and analysis I can’t do better than when I reviewed this for BookBrowse a few months after its release, so I’d direct you to the full text here. (It’s slightly depressing for me to go back to old reviews and see that I haven’t improved; if anything, I’ve gotten lazier.) A couple book club members weren’t as keen, I think because they’d read a lot of dystopian fiction or seen many postapocalyptic films and found this vision mild and with a somewhat implausible setup and tidy conclusion. But for me this and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road have persisted as THE literary depictions of post-apocalypse life because they perfectly blend the literary and the speculative in an accessible and believable way (this was a National Book Award finalist and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award), contrasting a harrowing future with nostalgia for an everyday life that we can already see retreating into the past.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

The two themes that most struck me this time were the enduring power of art and how societal breakdown would instantly eliminate the international – but compensate for it with the return of the extremely local. At a time when it feels difficult to trust central governments to have people’s best interests at heart, this is a rather comforting prospect. Just in my neighbourhood, I see how we implement this care on a small scale. In settlements of up to a few hundred, the remnants of Station Eleven create something like normal life by Year 20.

Book club members sniped that the characters could have better pooled skills, but we agreed that Mandel was wise to limit what could have been tedious details about survival. “Survival is insufficient,” as the Traveling Symphony’s motto goes (borrowed from Star Trek). Instead, she focuses on love, memory, and hunger for the arts. In some ways, this feels prescient of Covid-19, but even more so of the climate-related collapse I expect in my lifetime. I’ve rated this a little bit higher the second time for its lasting relevance. (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

Some favourite passages:

the whole of Chapter 6, a bittersweet litany that opens “An incomplete list: No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below” and includes “No more pharmaceuticals,” “No more flight,” and “No more countries”

“what made it bearable were the friendships, of course, the camaraderie and the music and the Shakespeare, the moments of transcendent beauty and joy”

“The beauty of this world where almost everyone was gone. If hell is other people, what is a world with almost no people in it?”

Astraea by Kate Kruimink (Weatherglass Novella Prize) #NovNov24

Astraea by Kate Kruimink is one of two winners* of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. Back in September, I was introduced to it through Weatherglass Books’ “The Future of the Novella” event in London (my write-up is here).

Taking place within about a day and a half on a 19th-century convict ship bound for Australia, it is the intense story of a group of women and children chafing against the constraints men have set for them. The protagonist is just 15 years old and postpartum. Within a hostile environment, the women have created an almost cosy community based on sisterhood. They look out for each other; an old midwife can still bestow her skills.

The ship was their shelter, the small chalice carrying them through that which was inhospitable to human life. But there was no shelter for her there, she thought. There was only a series of confines between which she might move but never escape.

The ship’s doctor and chaplain distrust what they call the “conspiracy of women” and are embarrassed by the bodily reality of one going into labour, another tending to an ill baby, and a third haemorrhaging. They have no doubt they know what is best for their charges yet can barely be bothered to learn their names.

Indeed, naming is key here. The main character is effectively erased from the historical record when a clerk incorrectly documents her as Maryanne Maginn. Maryanne’s only “maybe-friend,” red-haired Sarah, has the surname Ward. “Astraea” is the name not just of the ship they travel on but also of a star goddess and a new baby onboard.

The drama in this novella arises from the women’s attempts to assert their autonomy. Female rage and rebellion meet with punishment, including a memorable scene of solitary confinement. A carpenter then constructs a “nice little locking box that will hold you when you sin, until you’re sorry for it and your souls are much recovered,” as he tells the women. They are all convicts, and now their discipline will become a matter of religious theatrics.

Given the limitations of setting and time and the preponderance of dialogue, I could imagine this making a powerful play. The novella length is as useful a framework as the ship itself. Kruimink doesn’t waste time on backstory; what matters is not what these women have done to end up here, but how their treatment is an affront to their essential dignity. Even in such a low page count, though, there are intriguing traces of the past and future, as well as a fleeting hint of homoeroticism. I would recommend this to readers of The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, Devotion by Hannah Kent and Women Talking by Miriam Toews. And if you get a hankering to follow up on the story, you can: this functions as a prequel to Kruimink’s first novel, A Treacherous Country. (See also Cathy’s review.)

[115 pages]

With thanks to Weatherglass Books for the free copy for review.

*The other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths, will be published in January. I hope to have a proof copy in hand before the end of the month to review for this challenge plus SciFi Month.

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 (

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 ( I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels (

I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels ( The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after

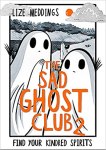

The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after  This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which

This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which