Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

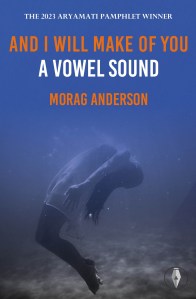

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

October Books: Ballard, Czarnecki, Moss, Oliver, Ostriker, Steed & More

Apparently October is THE biggest month of the year for new releases. A sterling set came my way this year, including two beautiful novella-length memoirs, a luxuriantly illustrated work dedicated to an everyday bird species, two very different but equally elegant poetry collections, and a book of offbeat comics. Time and concentration only allow for a paragraph or so on each, but I hope that gives a flavour of the contents and will pique interest in the ones that suit you best. Plus I excerpt and link to my BookBrowse review of a poignant story of sisters and mental illness, and my Shelf Awareness review of a fantastic graphic novel adaptation.

Bound: A Memoir of Making and Remaking by Maddie Ballard

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

I lower the needle and the world recedes. The process of sewing a garment – printing the pattern, tracing and cutting, sewing the first and the second and the fiftieth seam – is a lesson in taking your time.

Like gardening, sewing is an investment in the future – in what sort of person your future self will be, and how she will feel about her body, and what she will want to wear.

Similar to two other very short works of nonfiction I’ve read from The Emma Press, How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart by Florentyna Leow and Tiny Moons by Nina Mingya Powles (Ballard, too, is from New Zealand), this is a graceful, enriching book about a young woman making her way in the world and figuring out what is essential to her sense of home and identity. I commend it whether or not you have any particular interest in handicraft.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Encounters with Inscriptions: A Memoir Exploring Books Gifted by Parents by Kristin Czarnecki

When Kristin Czarnecki got in touch to offer a copy of her bibliomemoir about revisiting the books her late parents gifted her, I was instantly intrigued but couldn’t have known in advance how perfect it would be for me. Niche it might seem, but it combines several of my reading interests: bereavement, books about books, relationships with parents (especially a mother) and literary travels.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

It seems fitting to be reviewing this on the second anniversary of my mother’s death. The afterword, which follows on from the philosophical encouragement of a chapter on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, exhorts readers to cherish loved ones while we can – and be grateful for the tokens they leave behind. I had told Kristin about books my parents inscribed to me, as well as the journals I inherited from my mother. But I didn’t know there would be other specific connections between us, too, such as being childfree and hopeless in the kitchen. (Also, I have family in South Bend, Indiana, where she’s from, and our mothers were born in the first week of August.) All that to say, I felt that I found a kindred spirit in this lovely book, which is one of the nicest things that happens through reading.

With thanks to the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Starling: A Biography by Stephen Moss

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Overall, the style of the book is dry and slightly workmanlike. However, when he’s recounting murmurations he’s seen in Somerset or read about, Moss’s enthusiasm lifts it into something special. Autumn dusk is a great time to start watching out for starling gatherings. I love observing and listening to the starlings just in the treetops and aerials of my neighbourhood, but we do also have a small local murmuration that I try to catch at least a few times in the season. Here’s how he describes their magic: “At a time when, both as a society and as individuals, we are less and less in touch with the natural world, attending this fleeting but memorable event is a way we can reconnect, regain our primal sense of wonder – and still be home in time for tea.”

With thanks to Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage (Penguin Random House) for the free copy for review.

The Alcestis Machine by Carolyn Oliver

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

The Holy & Broken Bliss: Poems in Plague Time by Alicia Ostriker

“The words of an old woman shuffling the cards of her own decline the decline

of her husband the decline of her nation her plague-smitten world”

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

It is almost winter and still

as I walk to the clinic the gingkos

sing their seraphic air

as if there is no tomorrow

With thanks to Alice James Books for the advanced e-copy for review.

Forces of Nature by Edward Steed

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

With thanks to Drawn & Quarterly for the e-copy for review.

Reviewed for BookBrowse:

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

R.I.P., Part II: Duy Đoàn, T. Kingfisher & Rachael Smith

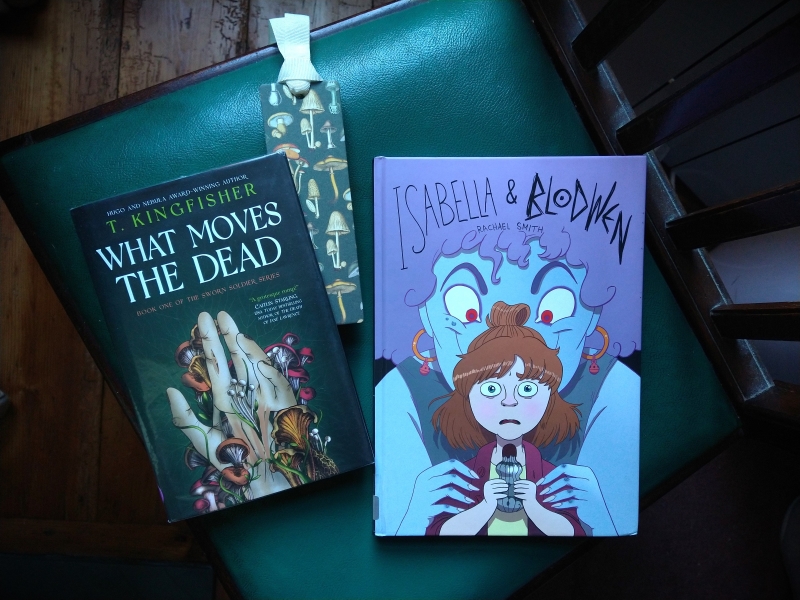

A second installment for the Readers Imbibing Peril challenge (first was a creepy short story collection). Zombies link my first two selections, an experimental poetry collection and a historical novella that updates a classic, followed by a YA graphic novel about a medieval witch who appears in contemporary life to help a teen deal with her problems. I don’t really do proper horror; I’d characterize all three of these as more mischievous than scary.

Zombie Vomit Mad Libs by Duy Đoàn

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

To be published in the USA by Alice James Books on November 12. With thanks to the publisher for the advanced e-copy for review.

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher (2022)

{MILD SPOILERS AHEAD}

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

At first it seemed the author was awkwardly inserting a nonbinary character into history, but it’s more complicated than that. The sworn soldier tradition in countries such as Albania was a way for women, especially orphans or those who didn’t have brothers to advocate for them, to have autonomy in martial, patriarchal cultures. Kingfisher makes up European nations and their languages, as well as special sets of pronouns to refer to soldiers (ka/kan), children (va/van), etc. She doesn’t belabour the world-building, just sketches in the bits needed.

This was a quick and reasonably engaging read, though I wasn’t always amused by Kingfisher’s gleefully anachronistic tone (“Mozart? Beethoven? Why are you asking me? It was music, it went dun-dun-dun-DUN, what more do you want me to say?”). I wondered if the plot might have been inspired by a detail in Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, but it seems more likely it’s a half-conscious addition to a body of malevolent-mushroom stories (Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, various by Jeff VanderMeer, The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley). I was drawn in by Easton’s voice and backstory enough to borrow the sequel, about which more anon. (T. Kingfisher is the pen name of Ursula Vernon.) (Public library)

Isabella & Blodwen by Rachael Smith (2023)

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

It’s a sweet enough story, but a few issues detracted from my enjoyment. Issy is often depicted more like a ten-year-old. I don’t love the blocky and exaggerated features Smith gives her characters, or the Technicolor hues. And I found myself rolling my eyes at how the book unnaturally inserts a sexual harassment theme – which Blodwen responds to in modern English, having spoken in archaic fashion up to that point, and with full understanding of the issue of consent. I can imagine younger teens enjoying this, though. (Public library)

The mini playlist I had going through my mind as I wrote this:

- “Running with Zombies” by The Bookshop Band (inspired by The Making of Zombie Wars by Aleksandar Hemon)

- “Flesh and Blood Dance” by Duke Special

- “Dead Alive” by The Shins

And to counterbalance the evil fungi of the Kingfisher novella, here’s Anne-Marie Sanderson employing the line “A mycelium network is listening to you” in a totally non-threatening way. It’s one of the multiple expressions of reassurance in her lovely song “All Your Atoms,” my current earworm from her terrific new album Old Light.

Three on a Theme: Trans Poetry for National Poetry Day

Today is National Poetry Day here in the UK. Alfie and I spent part of the chilly early morning reading from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s super Poetry Unbound, an anthology of 50 poems to which he’s devoted personal introductions and exploratory essays. He describes poetry as “like a flame: helping us find our way, keeping us warm.”

Poetry Unbound is also the name of his popular podcast; both were recommended to me by Sara Beth West, my fellow Shelf Awareness reviewer, in this interview we collaborated on back in April (National Poetry Month in the USA) about reading and reviewing poetry. I’ve been a keen reader of contemporary poetry for 15 years or so, but in the 3.5 years that I’ve been writing for Shelf I’ve really ramped up. Most months, I review a couple poetry collections for that site, and another one or more on here.

Two of my Shelf poetry reviews from the past 10 months highlight the trans experience; when I recently happened to read another collection by a trans woman, I decided to gather them together as a trio. All three pair the personal – a wrestling over identity – with the political, voicing protest at mistreatment.

Transitory by Subhaga Crystal Bacon (2023)

In her Isabella Gardner Award-winning fourth collection, queer poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon commemorates the 46 trans and gender-nonconforming people murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020—an “epidemic of violence” that coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The statistics Bacon conveys are heartbreaking: “The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years of age”; “Half of Black trans women spend time in jail”; “Trans people are anywhere/ between eleven and forty percent/ of the homeless population.” She also draws on her own experience of gender nonconformity: “A little butch./ A little femme.” She recalls of visiting drag bars in the 1980s: “We were all/ trying on gender.” And she vows: “No one can say a life is not right./ I have room for you in me.” Her poetic memorial is a valuable exercise in empathy.

Published by BOA Editions. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I was interested to note that the below poets initially published under both female and male, new and dead names, as shown on the book covers. However, a look at social media makes it clear that the trans women are now going exclusively by female names.

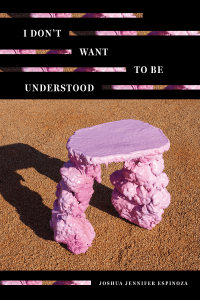

I Don’t Want to Be Understood by Jennifer Espinoza (2024)

In Espinoza’s undaunted fourth poetry collection, transgender identity allows for reinvention but also entails fear of physical and legislative violence.

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Words build into stanzas, prose paragraphs, a zigzag line, or cross-hatching. Espinoza likens the body to a vessel for traumatic memories: “time is a body full of damage// that is constantly trying to forget.” Alliteration and repetition construct litanies of rejection but, ultimately, of hope: “When I call myself a woman I am praying.”

Published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

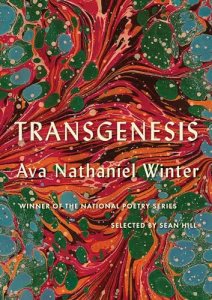

Transgenesis by Ava Winter (2024)

“The body is holy / and is made holy in its changing.”

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Let me greet now,

with warm embrace,

the small blue tablets

I place beneath my tongue each morning.

Oh estradiol,

daily reminder

of what our bodies

have always known:

the many forms of beauty that might be made

flesh by desire, by chance, by animal action.

(from “Transgenesis”)

The first time I wore a dress in public without a hint of irony—a Max Mara wrap adorned with Japanese lilies that framed my shoulders perfectly—I was still thin but also thickly bearded and men on the train whispered to me in a conspiratorial tone, as if they hoped the dress were a joke I might let them in on.

(from “WWII SS Wiking Division Badge, $55”)

– and faith grants affirmation that “there is beauty in such queer and fruitless bodies,” as the title poem insists, with reference to the saris (nonbinary person) acknowledged by the Talmudic rabbis. “Lament with Cello Accompaniment” provides an achingly gorgeous end to the collection:

I do not choose the sound of the song

In my mouth, the fading taste of what I still live through, but I choose this future, as I bury a name defined by grief, as I enter the silence where my voice will take shape.

Winter teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I’ll look out for more of her work.

Published by Milkweed Editions. (Read via Edelweiss)

More trans poetry I have read:

A Kingdom of Love & Eleanor Among the Saints by Rachel Mann

By nonbinary/gender-nonconforming poets, I have also read:

Surge by Jay Bernard

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest

Binded by H Warren

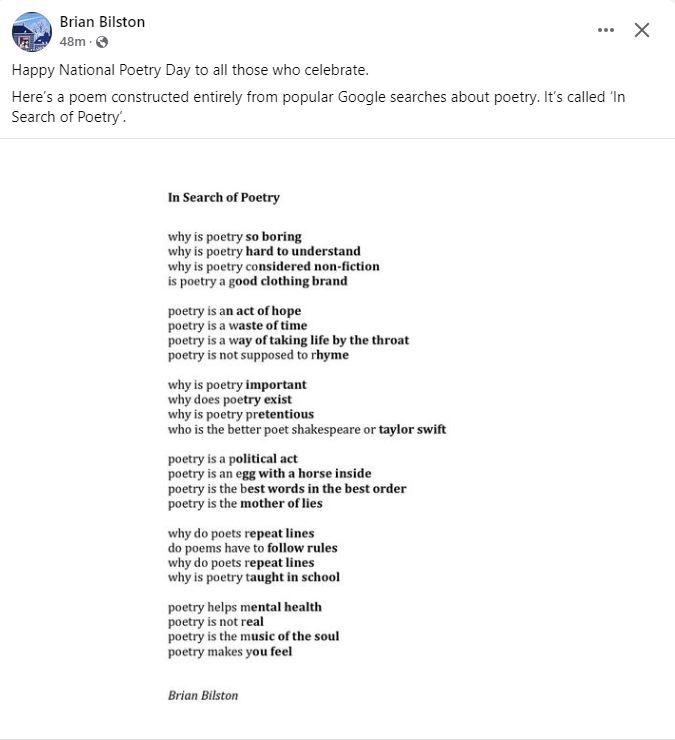

Extra goodies for National Poetry Day:

Follow Brian Bilston to add a bit of joy to your feed.

Editor Rosie Storey Hilton announces a poetry anthology Saraband are going to be releasing later this month, Green Verse: Poems for our Planet. I’ll hope to review it soon.

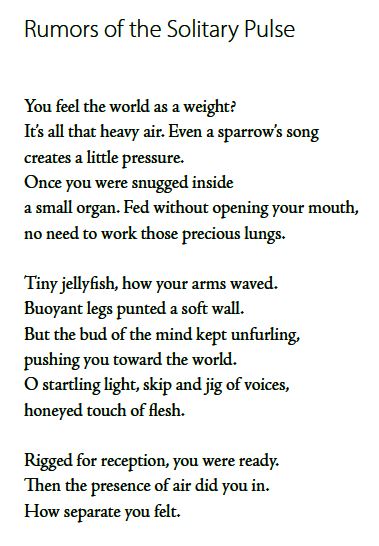

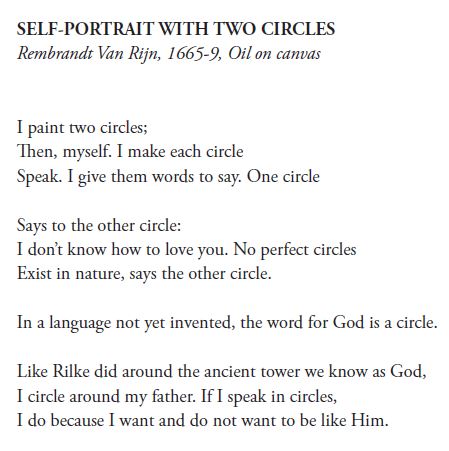

Two poems that have been taking the top of my head off recently (in Emily Dickinson’s phrasing), from Poetry Unbound (left) and Seamus Heaney’s Field Work:

Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

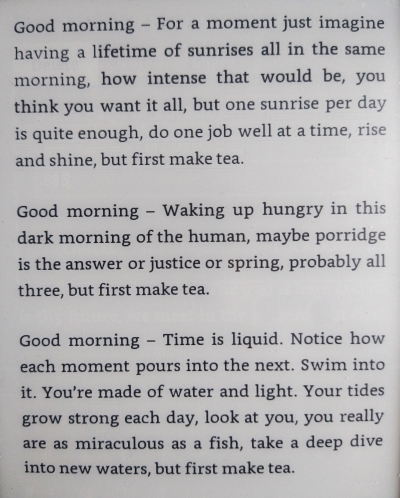

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

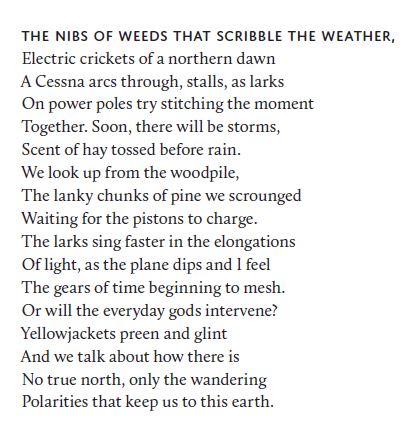

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

With thanks to Alice James Books for the e-copy for review.

From Base Materials by Jenny Lewis

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

“On Translation”

The trouble with translating, for me, is that

when I’ve finished, my own words won’t come;

like unloved step-children in a second marriage,

they hang back at table, knowing their place.

While their favoured siblings hold forth, take

centre stage, mine remain faint, out of ear-shot

like Miranda on her island shore before the boats

came near enough, signalling a lost language;

and always the boom of another surf – pounding,

subterranean, masculine, urgent – makes my words

dither and flit, become little and scattered

like flickering shoals caught up in the slipstream

of a whale, small as sand crabs at the bottom of a bucket,

harmless; transparent as zooplankton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

“Holy”

The days lengthen, the sky quickens.

Something invisible flows in the sticks

and they blossom. We learn to let this

be enough. It isn’t; it’s enough to go on.

Then a lull and a clip on my phone

of a small girl playing with a tennis ball

her three-year-old face a chalice brimming

with life, and I promise when all this is over

I will remember what is holy. I will say

the word without shame, and ask if God

was his own fable to help us bear absence,

the cold space at the heart of the atom.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

Poetry Review Catch-up: Burch, Carrick-Varty, Davidson, Marya, Parsons (#ReadIndies)

As Read Indies month continues, I’m catching up on poetry collections I’ve been sent by three independent publishers: the UK’s Carcanet Press, and Alice James Books and Terrapin Press, both based in the USA. Various as these five are in style and technique, nature and family ties are linking themes. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

Leave Me a Little Want by Beverly Burch (2022)

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty (2023)

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Arctic Elegies by Peter Davidson (2022)

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Wonderful is the patience of the snow

And glorious the violence of the cold.

How lovely is the power of the dark pole

To draw the iron and move the compass rose.

As cold as loss as cold as freezing steel

In this same vein, I also appreciated the wry “The Museum of Loss” and the ornate “The Mourning Virtuoso.” There’s a bit of an Auden flavour here, but the niche topics didn’t always hold my attention.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

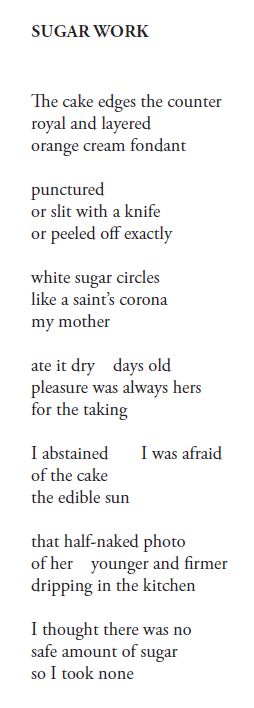

Sugar Work by Katie Marya (2022)

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

With thanks to Alyson Sinclair PR for the free e-copy for review.

The Mayapple Forest by Kim Ports Parsons (2022)

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

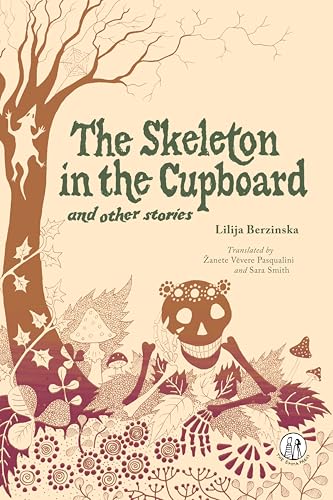

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,  The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues.

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues.

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.