Spring Reads, Part II: Blossomise, Spring Chicken & Cold Spring Harbor

Our garden is an unruly assortment of wildflowers, rosebushes, fruit trees and hedge plants, along with an in-progress pond, and we’ve made a few half-hearted attempts at planting vegetable seeds and flower bulbs. It felt more like summer earlier in May, before we left for France; as the rest of the spring plays out, we’ll see if the beetroot, courgettes, radishes and tomatoes amount to anything. The gladioli have certainly been shooting for the sky!

I recently encountered spring (if only in name) through these three books, a truly mixed bag: a novelty poetry book memorable more for the illustrations than for the words, a fascinating popular account of the science of ageing, and a typically depressing (if you know the author, anyway) novel about failing marriages and families. Part I of my Spring Reading was here.

Blossomise by Simon Armitage; illus. Angela Harding (2024)

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

A favourite passage: “Scented and powdered / she’s staging / a one-tree show / with hi-viz blossoms / and lip-gloss petals; / she’ll season the pavements / and polished stones / with something like snow.” (Public library) ![]()

Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (or Die Trying) by Bill Gifford (2015)

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Over the course of the book, Gifford meets all number of researchers and cranks as he attends conferences, travels to spend time with centenarians and scientists, and participates in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. There have been some truly zany ideas about how to pause or reverse aging, such as self-dosing with hormones (Suzanne Somers is one proponent), but long-term use is discouraged. Some things that do help, to an extent, are calorie restriction and periodic fasting plus, possibly, red wine, coffee and aspirin. But the basic advice is nothing we don’t already know about health: don’t eat too much and exercise, i.e., avoid obesity. The layman-interpreting-science approach reminded me of Mary Roach’s. There was some crossover in content with Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine and various books I’ve read about dementia. Fun and enlightening. (New purchase – bargain book from Dollar Tree, Bowie, MD) ![]()

Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (1986)

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Evan and Rachel soon marry and agree to Gloria’s plan of sharing a house in Cold Spring Harbor, where the Shepards live (Evan’s mother is also an alcoholic, but less functional; she hides behind the “invalid” label). Take it from me: living with your in-laws is never a good idea! As the Second World War looms, and with Evan and Rachel expecting a baby, it’s clear something will have to give with this uneasy family arrangement, but the dramatic break I was expecting – along the lines of a death or accident – never arrived. Instead, there’s just additional slow crumbling, and the promise of greater suffering to come. Although Yates’s character portraits are as penetrating as in Easter Parade, I found the plot a little lacklustre here. (Secondhand – Clutterbooks, Sedbergh) ![]()

Any ‘spring’ reads for you recently?

Books of Summer, 2: The Story of My Father by Sue Miller

I followed up my third Sue Miller novel, The Lake Shore Limited, with her only work of nonfiction, a short memoir about her father’s decline with Alzheimer’s and eventual death. James Nichols was an ordained minister and church historian who had been a professor or dean at several of the USA’s most elite universities. The first sign that something was wrong was when, one morning in June 1986, she got a call from police in western Massachusetts who had found him wandering around disoriented and knocking at people’s doors at 3 a.m. On the road and in her house after she picked him up, he described vivid visual delusions. He still had the capacity to smile “ruefully” and reply, when Miller explained what had happened and how his experience differed from reality, “Doggone, I never thought I’d lose my mind.”

Until his death five years later, she was the primary person concerned with his wellbeing. She doesn’t say much about her siblings, but there’s a hint of bitterness that the burden fell to her. “Throughout my father’s disease, I struggled with myself to come up with the helpful response, the loving response, the ethical response,” she writes. “I wanted to give him as much of myself as I could. But I also wanted, of course, to have my own life. I wanted, for instance to be able to work productively.” She had only recently found success with fiction in her forties and published two novels before her father died; she dedicated the second to him, but too late for him to understand the honor. Her main comfort was that he never stopped being able to recognize her when she came to visit.

Although the book moves inexorably towards a death, Miller lightens it with many warm and admiring stories from her father’s past. Acknowledging that she’ll never be able to convey the whole of his personality, she still manages to give a clear sense of who he was, and the trajectory of his illness, all within 170 pages. The sudden death of her mother, a flamboyant lyric poet, at age 60 of a heart attack, is a counterbalance as well as a potential contributing factor to his slow fading as each ability was cruelly taken from him: living alone, reading, going outside for walks, sleeping unfettered.

Sutton Hill, the nursing home where he lived out his final years, did not have a dedicated dementia ward, and Miller regrets that he did not receive the specialist care he needed. “I think this is the hardest lesson about Alzheimer’s disease for a caregiver: you can never do enough to make a difference in the course of the disease. Hard because what we feel anyway is that we have never done enough. We blame ourselves. We always find ourselves deficient in devotion.” She conceived of this book as a way of giving her father back his dignity and making a coherent story out of what, while she was living through it, felt like a chaotic disaster. “I would snatch him back from the meaninglessness of Alzheimer’s disease.”

And in the midst of it all, there were still humorous moments. Her poor father fell in love with his private nurse, Marlene, and believed he was married to her. Awful as it was, there was also comedy in an extended family story Miller tells, one I think I’m unlikely to forget: They had always vacationed in New Hampshire rental homes, and when her father learned one of the opulent ‘cottages’ was coming up for sale, he agreed to buy it sight unseen. The seller was a hoarder … of cats. Eighty of them. He had given up cleaning up after them long ago. When they went to view the house her father had already dropped $30,000 on, it was a horror. Every floor was covered inches deep in calcified feces. It took her family an entire summer to clean the place and make it even minimally habitable. Only afterwards could she appreciate the incident as an early sign of her father’s impaired decision making.

I’ve read a fair few dementia-themed memoirs now. As people live longer, this suite of conditions is only going to become more common; if it hasn’t affected one of your own loved ones, you likely have a friend or neighbor who has had it in their family. This reminded me of other clear-eyed, compassionate yet wry accounts I’ve read by daughter-caregivers Elizabeth Hay (All Things Consoled) and Maya Shanbhag Lang (What We Carry). It was just right as a pre-Father’s Day read, and a novelty for fans of Miller’s novels. (Charity shop)

Recommended April Releases by Amy Bloom, Sarah Manguso & Sara Rauch

Just two weeks until moving day – we’ve got a long weekend ahead of us of sanding, painting, packing and gardening. As busy as I am with house stuff, I’m endeavouring to keep up with the new releases publishers have been so good as to send me. Today I review three short works: the story of accompanying a beloved husband to Switzerland for an assisted suicide, a coolly perceptive novella of American girlhood, and a vivid memoir of two momentous relationships. (April was a big month for new books: I have another 6–8 on the go that I’ll be catching up on in the future.) All:

In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Amy Bloom

“We’re not here for a long time, we’re here for a good time.”

(Ameche family saying)

Given the psychological astuteness of her fiction, it’s no surprise that Bloom is a practicing psychotherapist. She treats her own life with the same compassionate understanding, and even though the main events covered in this brilliantly understated memoir only occurred two and a bit years ago, she has remarkable perspective and avoids self-pity and mawkishness. Her husband, Brian Ameche, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in his mid-60s, having exhibited mild cognitive impairment for several years. Brian quickly resolved to make a dignified exit while he still, mostly, had his faculties. But he needed Bloom’s help.

“I worry, sometimes, that a better wife, certainly a different wife, would have said no, would have insisted on keeping her husband in this world until his body gave out. It seems to me that I’m doing the right thing, in supporting Brian in his decision, but it would feel better and easier if he could make all the arrangements himself and I could just be a dutiful duckling, following in his wake. Of course, if he could make all the arrangements himself, he wouldn’t have Alzheimer’s”

U.S. cover

She achieves the perfect tone, mixing black humour with teeth-gritted practicality. Research into acquiring sodium pentobarbital via doctor friends soon hit a dead end and they settled instead on flying to Switzerland for an assisted suicide through Dignitas – a proven but bureaucracy-ridden and expensive method. The first quarter of the book is a day-by-day diary of their January 2020 trip to Zurich as they perform the farce of a couple on vacation. A long central section surveys their relationship – a second chance for both of them in midlife – and how Brian, a strapping Yale sportsman and accomplished architect, gradually descended into confusion and dependence. The assisted suicide itself, and the aftermath as she returns to the USA and organizes a memorial service, fill a matter-of-fact 20 pages towards the close.

Hard as parts of this are to read, there are so many lovely moments of kindness (the letter her psychotherapist writes about Brian’s condition to clinch their place at Dignitas!) and laughter, despite it all (Brian’s endless fishing stories!). While Bloom doesn’t spare herself here, diligently documenting times when she was impatient and petty, she doesn’t come across as impossibly brave or stoic. She was just doing what she felt she had to, to show her love for Brian, and weeping all the way. An essential, compelling read.

With thanks to Granta for the free copy for review.

Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso

I’ve read Manguso’s four nonfiction works and especially love her Wellcome Book Prize-shortlisted medical memoir The Two Kinds of Decay. The aphoristic style she developed in her two previous books continues here as discrete paragraphs and brief vignettes build to a gloomy portrait of Ruthie’s archetypical affection-starved childhood in the fictional Massachusetts town of Waitsfield in the 1980s and 90s. She’s an only child whose parents no doubt were doing their best after emotionally stunted upbringings but never managed to make her feel unconditionally loved. Praise is always qualified and stingily administered. Ruthie feels like a burden and escapes into her imaginings of how local Brahmins – Cabots and Emersons and Lowells – lived. Her family is cash-poor compared to their neighbours and loves nothing more than a trip to the dump: “My parents weren’t after shiny things or even beautiful things; they simply liked getting things that stupid people threw away.”

The depiction of Ruthie’s narcissistic mother is especially acute. She has to make everything about her; any minor success of her daughter’s is a blow to her own ego. I marked out an excruciating passage that made me feel so sorry for this character. A European friend of the family visits and Ruthie’s mother serves corn muffins that he seems to appreciate.

My mother brought up her triumph for years. … She’d believed his praise was genuine. She hadn’t noticed that he’d pegged her as a person who would snatch up any compliment into the maw of her unloved, throbbing little heart.

U.S. cover

At school, as in her home life, Ruthie dissociates herself from every potentially traumatic situation. “My life felt unreal and I felt half-invested. I felt indistinct, like someone else’s dream.” Her friend circle is an abbreviated A–Z of girlhood: Amber, Bee, Charlie and Colleen. “Odd” men – meaning sexual predators – seem to be everywhere and these adolescent girls are horribly vulnerable. Molestation is such an open secret in the world of the novel that Ruthie assumes this is why her mother is the way she is.

While the #MeToo theme didn’t resonate with me personally, so much else did. Chemistry class, sleepovers, getting one’s first period, falling off a bike: this is the stuff of girlhood – if not universally, then certainly for the (largely pre-tech) American 1990s as I experienced them. I found myself inhabiting memories I hadn’t revisited for years, and a thought came that had perhaps never occurred to me before: for our time and area, my family was poor, too. I’m grateful for my ignorance: what scarred Ruthie passed me by; I was a purely happy child. But I think my sister, born seven years earlier, suffered more, in ways that she’d recognize here. This has something of the flavour of Eileen and My Name Is Lucy Barton and reads like autofiction even though it’s not presented as such. The style and contents may well be divisive. I’ll be curious to hear if other readers see themselves in its sketches of childhood.

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

XO by Sara Rauch

Sara Rauch won the Electric Book Award for her short story collection What Shines from It. This compact autobiographical parcel focuses on a point in her early thirties when she lived with a long-time female partner, “Piper”, and had an intense affair with “Liam”, a fellow writer she met at a residency.

“no one sets out in search of buried treasure when they’re content with life as it is”

“Longing isn’t cheating (of this I was certain), even when it brushes its whiskers against your cheek.”

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

This reminded me of a number of books I’ve read about short-lived affairs – Tides, The Instant – and about renegotiating relationships in a queer life – The Fixed Stars, In the Dream House – but felt most like reading a May Sarton journal for how intimately it recreates daily routines of writing, cooking, caring for cats, and weighing up past, present and future. Lovely stuff.

With thanks to publicist Lori Hettler and Autofocus Books for the e-copy for review.

Will you seek out one or more of these books?

What other April releases can you recommend?

January Releases II: Nick Blackburn, Wendy Mitchell & Padraig Regan

The January new releases continue! I’ll have a final batch of three tomorrow. For today, I have an all-over-the-place meditation masquerading as a bereavement memoir, an insider’s look at what daily life with dementia is like, and a nonbinary poet’s debut.

The Reactor: A Book about Grief and Repair by Nick Blackburn

I’ll read any bereavement memoir going, and the cover commendations from Olivia Laing and Helen Macdonald made this seem like a sure bet. Unfortunately, this is not a bereavement memoir but an exercise in self-pity and free association. The book opens two weeks after Blackburn’s father’s death – “You have died but it’s fine, Dad.” – and proceeds in titled fragments of one line to a few paragraphs. Blackburn sometimes addresses his late father directly, but more often the “you” is himself. He becomes obsessed with the Chernobyl disaster (even travelling to Belarus), which provides the overriding, and overstretched, title metaphor – “the workings of grief are unconscious, invisible. Like radiation.”

From here the author indulges in pop culture references and word association: Alexander McQueen’s fashion shows, Joni Mitchell’s music, Ingmar Bergman’s films, Salvador Dalí’s paintings and so on. These I at least recognized; there were plenty of other random allusions that meant nothing to me. All of this feels obfuscating, as if Blackburn is just keeping busy: moving physically and mentally to distract from his own feelings. A therapist focusing on LGBT issues, he surely recognizes his own strategy here. This seems like a diary you’d keep in a bedside drawer (there’s also the annoyance of no proper italicization or quotation marks for works of art), not something you’d try to get published as a bereavement memoir.

From here the author indulges in pop culture references and word association: Alexander McQueen’s fashion shows, Joni Mitchell’s music, Ingmar Bergman’s films, Salvador Dalí’s paintings and so on. These I at least recognized; there were plenty of other random allusions that meant nothing to me. All of this feels obfuscating, as if Blackburn is just keeping busy: moving physically and mentally to distract from his own feelings. A therapist focusing on LGBT issues, he surely recognizes his own strategy here. This seems like a diary you’d keep in a bedside drawer (there’s also the annoyance of no proper italicization or quotation marks for works of art), not something you’d try to get published as a bereavement memoir.

The bigger problem is there is no real attempt to convey a sense of his father. It would be instructive to go back and count how many pages actually mention his father. One page on his death; a couple fleeting mentions of his mental illness being treated with ECT and lithium. Most revealing of all, ironically, is the text of a postcard he wrote to his mother on a 1963 school trip to Austria. “I want to tell you more about my father, but honestly I feel like I hardly knew him. There was always his body and that was enough,” Blackburn writes. Weaselling out of his one task – to recreate his father for readers – made this an affected dud.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

What I Wish People Knew About Dementia: From Someone Who Knows by Wendy Mitchell

I loved Mitchell’s first book, Somebody I Used to Know. She was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s at age 58 in 2014. This follow-up, too, was co-written with Anna Wharton (they have each written interesting articles on their collaboration process, here and here). Whereas her previous work was a straightforward memoir, this has more of a teaching focus, going point by point through the major changes dementia causes to the senses, relationships, communication, one’s reaction to one’s environment, emotions, and attitudes.

I kept shaking my head at all these effects that would never have occurred to me. You tend not to think beyond memory. Food is a major issue for Mitchell: she has to set iPad reminders to eat, and chooses the same simple meals every time. Pasta bowls work best for people with dementia as they can get confused trying to push food around a plate. She is extra sensitive to noises and may have visual and olfactory hallucinations. Sometimes she is asked to comment on dementia-friendly building design. For instance, a marble floor in a lobby looks like water and scares her, whereas clear signage and bright colours cheer up a hospital trip.

I kept shaking my head at all these effects that would never have occurred to me. You tend not to think beyond memory. Food is a major issue for Mitchell: she has to set iPad reminders to eat, and chooses the same simple meals every time. Pasta bowls work best for people with dementia as they can get confused trying to push food around a plate. She is extra sensitive to noises and may have visual and olfactory hallucinations. Sometimes she is asked to comment on dementia-friendly building design. For instance, a marble floor in a lobby looks like water and scares her, whereas clear signage and bright colours cheer up a hospital trip.

The text also includes anonymous input from her friends with dementia, and excerpts from recent academic research on what can help. Mitchell and others with Alzheimer’s often feel written off by their doctors – her diagnosis appointment was especially pessimistic – but her position is that the focus should be on what people can still do and adaptations that will improve their everyday lives. Mitchell lives alone in a small Yorkshire village and loves documenting the turning of the seasons through photographs she shares on social media. She notes that it’s important for people to live in the moment and continue finding activities that promote a flow state, a contrast to some days that pass in a brain haze.

This achieves just what it sets out to: give a picture of dementia from the inside. As it’s not a narrative, it’s probably best read in small doses, but there are some great stories along the way, like the epilogue’s account of her skydive to raise money for Young Dementia UK.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

The sensual poems in this debut collection are driven by curiosity, hunger and queer desire. Flora and foods are described as teasing mystery, with cheeky detail:

I’m thinking of how mushrooms will haunt a wet log like bulbous ghosts

The chicken is spatchcocked & nothing

like a book, but it lies open & creases

where its spine once was.

For as long as it take a single drop of condensation to roll its path

down the curve of a mojito glass before it’s lost in the bare wood of the table,

everything is held // in its hall of mirrors

An unusual devotion to ampersands; an erotic response to statuary, reminiscent of Richard Scott; alternating between bold sexuality and masochism to the point of not even wanting to exist; a central essay on the Orlando nightclub shooting and videogames – the book kept surprising me. I loved the fertile imagery, and appreciated Regan’s exploration of a nonbinary identity:

An unusual devotion to ampersands; an erotic response to statuary, reminiscent of Richard Scott; alternating between bold sexuality and masochism to the point of not even wanting to exist; a central essay on the Orlando nightclub shooting and videogames – the book kept surprising me. I loved the fertile imagery, and appreciated Regan’s exploration of a nonbinary identity:

Often I envy the Scandinavians for their months of sun,

unpunctuated. I think I want some kind of salad. I want to feel like a real boy, sometimes.

Thank you

for this chain of daisies to wear around my neck — it makes me look so pretty.

Highly recommended, especially to readers of Séan Hewitt and Stephen Sexton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Does one of these books appeal to you?

Catching Up: Mini Reviews of Some Notable Reads from Last Year

I do all my composition on an ancient PC (unconnected to the Internet) in a corner of our lounge. On top of the CPU sit piles of books waiting to be reviewed. Some have been residing there for an embarrassingly long time since I finished reading them; others were only recently added to the stack but had previously languished on my set-aside shelf. I think the ‘oldest’ of the set below is the Olson, which I started reading in November 2019. In every case, the book earned a spot on the pile because I felt it was worth a review, but I’ll stick to a brief paragraph on why each was memorable. Bonus: I get my Post-its back, and can reshelve the books so they get packed sensibly for our upcoming move.

Fiction

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

Nonfiction

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both  The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.

The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read ( In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.  Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.

Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.  February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

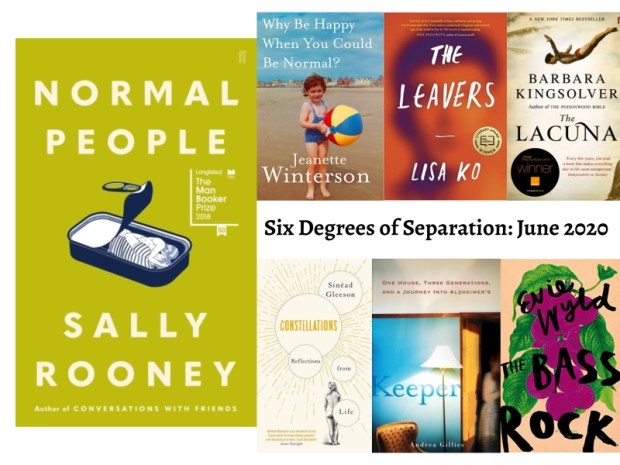

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full  Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of  A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life.

A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life. Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via

Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via