Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

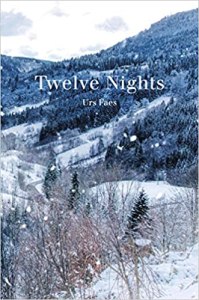

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

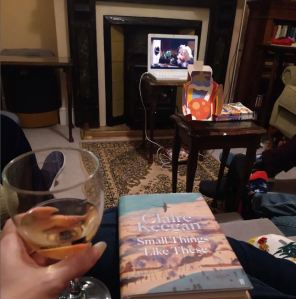

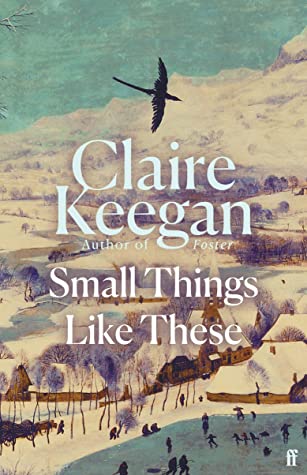

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

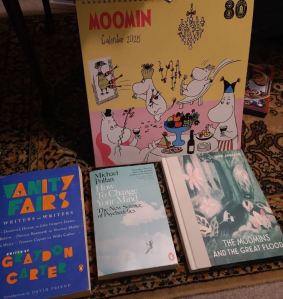

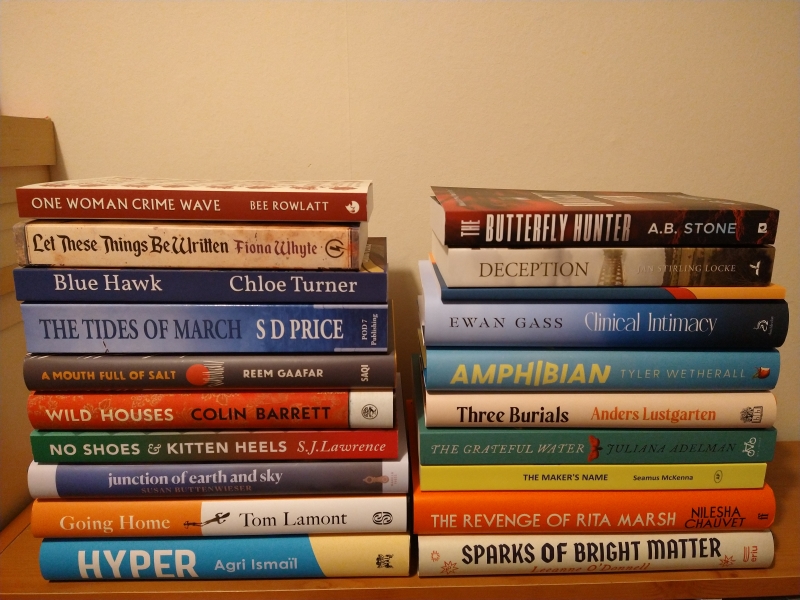

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

Interview with Neil Griffiths of Weatherglass Books (#NovNov24)

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Samantha Harvey’s 136-page Orbital won the Booker Prize, the film adaptation of Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is in cinemas: Is the novella having a moment? If so, how do you account for its fresh prominence? Or has it always been a powerful form and we’re realizing it anew?

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

My co-founder of Weatherglass, Damian Lanigan, says this: “the novella is the form for our times: befitting our short attention spans, but also with its tight focus, with its singular atmosphere – it’s the ideal form for glimpsing something essential about the world and ourselves in an increasingly chaotic world.”

But then if we look over the history of the prose fiction over the last 200 hundred years, there are so many novellas that have defined an era: Turgenev’s Love, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Carr’s A Month in the Country, Orwell’s Animal Farm, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Why did Weatherglass choose to focus on short books? Do economic and environmental factors come into it (short books = less paper = lower printing costs as well as fewer trees cut down)?

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Neil Griffiths

We’ve heard about the bloating of films, that they’re something like 20% longer on average than they were 40 years ago; will books take the opposite trajectory? Can a one-sitting read compete with a film?

I don’t think I’ve ever read even the shortest novella in one sitting. I need time to reflect. I don’t think comparing the two forms is helpful because they require different things of us. Take music: Morton Feldman’s 2nd String Quartet is 5 hours long, without a break. I’d commit to that in the concert hall, but I couldn’t read for 5 hours without a break or sit through a film.

How did you bring Ali Smith on board as the judge for the first two years of the Weatherglass Novella Prize? There was a blind judging process and you ended up with an all-female shortlist in the inaugural year. Do you have a theory as to why?

Ali Smith

Damian kept saying Ali Smith would be the best judge and I kept saying “but how do we get to her?” Then someone told me they had her email address. I didn’t expect to get an answer. A ‘Yes’ came an hour later. She’s been wonderful to work with. And she’s enjoyed it so much she’s agreed to do it ongoingly.

I do think the shortlist question is an important one. Certainly we don’t have to ask ourselves any questions when it’s an all-female short list, but we would if it was all-male. What does that say? I don’t know why the strongest were by women.

Do you have any personal favourite novellas?

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

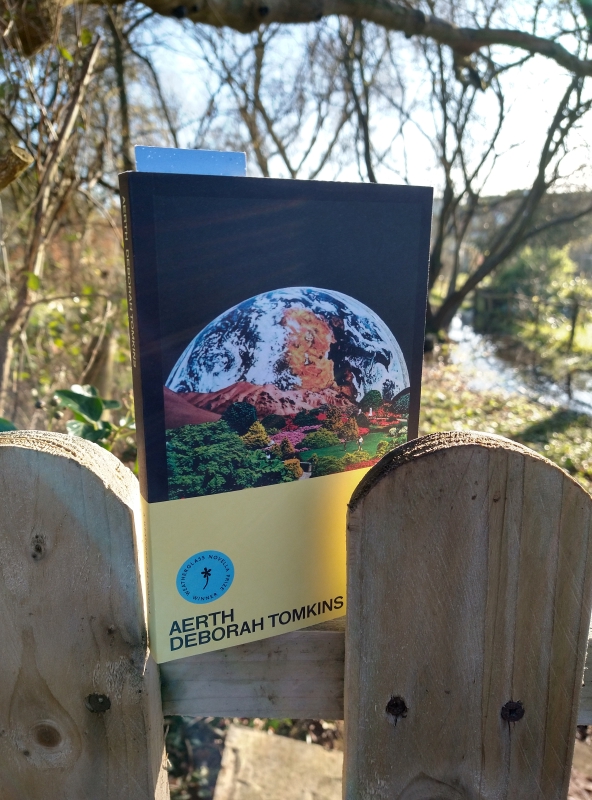

*Though it won’t be published until 25 January, I have a finished copy of the other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths and incorporating second- and third-person narration and various formats. I’ve been enjoying it so far and hope to review it soon as my first recommendation for 2025.

#NovNov24 Halfway Check-In & Small Things Like These Film Review

Somehow half of November has flown by. We hope you’ve been enjoying reading and reviewing short books this month. So far we have had 40 participants and 84 posts! Remember to add your posts to the link-up, or alert us via a comment here or on Bluesky (@cathybrown746.bsky.social / @bookishbeck.bsky.social), Instagram (@cathy_746books / @bookishbeck), or X (@cathy746books / @bookishbeck).

If you haven’t already, there’s no better time to pick up our buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey, which won the Booker Prize on Tuesday evening. Chair of judges Edmund de Waal said it is “about a wounded world” and that the panel’s “unanimity about Orbital recognises its beauty and ambition.” I was surprised to learn that it is only the second-shortest Booker winner; Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald is even shorter.

Another popular novella many of us have read is Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (my latest review is here). I went to see the excellent film adaptation, with a few friends from book club, at our tiny local arthouse cinema on Wednesday afternoon. I’ve read the book twice now – I might just read it a third time before Christmas – and from memory the film is remarkably faithful to its storyline and scope. (The only significant change I think of is that Bill doesn’t visit Ned in the hospital, but there are still flashbacks to the role that Ned played in Bill’s early life.)

The casting and cinematography are exceptional. Cillian Murphy portrays Bill with just the right blend of stoicism, meekness, and angst. Emily Watson is chilling as Sister Mary, the Mother Superior of the convent, which is suitably creepy with dim brick hallways and clinical laundry rooms. The grimy cobbles and dull streetlamps of the town contrast with the warm light in the scenes of Bill’s remembered childhood at Mrs Wilson’s. Repeated shots – of Bill’s truck setting off across the bridge in the early morning, of him scrubbing coal dust from his hands with carbolic soap, of his eyes wide open in the middle of the night – are not recursive but a way of establishing the gruelling nature of his tasks and the unease that plagues him. A life of physical labour has aged him beyond 39 (cf. Murphy is 48) and he’s in pain from shouldering sacks of coal day in and day out.

The casting and cinematography are exceptional. Cillian Murphy portrays Bill with just the right blend of stoicism, meekness, and angst. Emily Watson is chilling as Sister Mary, the Mother Superior of the convent, which is suitably creepy with dim brick hallways and clinical laundry rooms. The grimy cobbles and dull streetlamps of the town contrast with the warm light in the scenes of Bill’s remembered childhood at Mrs Wilson’s. Repeated shots – of Bill’s truck setting off across the bridge in the early morning, of him scrubbing coal dust from his hands with carbolic soap, of his eyes wide open in the middle of the night – are not recursive but a way of establishing the gruelling nature of his tasks and the unease that plagues him. A life of physical labour has aged him beyond 39 (cf. Murphy is 48) and he’s in pain from shouldering sacks of coal day in and day out.

Both book and film are set in 1985 but apart from the fashions and the kitschy Christmas decorations and window dressings you’d be excused for thinking it was the 1950s. Bill’s business deals in coal, peat and tinder; rural Ireland really was that economically depressed and technologically constrained. (Another Ireland-set film I saw last year, The Miracle Club, is visually very similar – it even features two of the same actors – although it takes place in 1967. It’s as if nothing changed for decades.)

By its nature, the film has to be a little more overt about what Bill is feeling (and generally not saying, as he is such a quiet man): there are tears at Murphy’s eyes and anxious breathing to make Bill’s state of mind obvious. Yet the film retains much of the subtlety of Keegan’s novella. You have to listen carefully during the conversation between Bill and Sister Mary to understand she is attempting to blackmail him into silence about what goes on at the convent.

By its nature, the film has to be a little more overt about what Bill is feeling (and generally not saying, as he is such a quiet man): there are tears at Murphy’s eyes and anxious breathing to make Bill’s state of mind obvious. Yet the film retains much of the subtlety of Keegan’s novella. You have to listen carefully during the conversation between Bill and Sister Mary to understand she is attempting to blackmail him into silence about what goes on at the convent.

At the end of the film showing, you could have heard a pin drop. Everyone was stunned at the simple beauty of the final scene, and the statistics its story is based on. It’s truly astonishing that Magdalene Laundries were in operation until the late 1990s, with Church support. Rage and sorrow build in you at the very thought, but Bill’s quietly heroic act of resistance is an inspiration. What might we, ordinary people all, be called on to do for women, the poor, and the oppressed in the years to come? We have no excuse not to advocate for them.

(Arti of Ripple Effects has also reviewed the film here.)

So far this month I’ve read nine novellas and reviewed eight. One of these was a one-sitting read, and I have another pile of ones that I could potentially read of a morning or evening next week. I’m currently reading another 16 … it remains to be seen whether I will average one a day for the month!

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler,” as Joe Hill said. Hard to believe, but it’s now the FIFTH year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogger/social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella is a book of 20,000 to 40,000 words, but because that’s hard for a reader to gauge, we tend to say anything under 200 pages (even nonfiction). I’m going to make it a personal challenge to limit myself to books of ~150 pages or less.

We’re keeping it simple this year with just the one buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey. (Though we chose it weeks ago, its shortlisting for the Booker Prize is all the more reason to read it!) The UK hardback has 144 pages. Here’s part of the blurb to entice you:

“Six astronauts rotate in their spacecraft above the earth. … Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. … They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?”

Please join us in reading it at any time between now and the end of November!

We won’t have any official themes or prompts, but you might want to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last NovNov, and finish it with a New to My TBR list based on what novellas others have tempted you to try in the future.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

“The Future of the Novella”

On the 11th, at Foyles in London, I attended a perfect event to get me geared up for Novellas in November. Indie publisher Weatherglass Books and judge Ali Smith introduced us to the two winners she chose for the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize: Kate Kruimink’s Astraea (set on a 19th-century Australian convict ship), out now, and Deborah Tomkins’ Aerth (a sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative earths), coming out in January.

Ali Smith

We heard readings from both novellas, and Neil Griffiths and Damian Lanigan of Weatherglass told us some more about what they publish and the process of reading the prize submissions (blind!). Lanigan called the novella “a form for our times” and put this down not just to modern attention spans but to focus – the glimpse of something essential. He and Smith mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald, Claire Keegan, Françoise Sagan and Muriel Spark as some of the masters of the novella form.

The effortlessly cool Smith spoke about the delight of spending weekend mornings – she writes during the week but gives herself the weekends off to read – in bed with a pot of coffee and a Weatherglass novella. She particularly enjoyed going into each book from the shortlist without any context and lamented that blurbs mean the story has to be, to some extent, given away to the reader. She said the ending of a novella has to land “like a cat, on its feet” (Griffiths then appended that it must also be ambiguous).

Kate Kruimink

Kruimink, who edits short stories for a magazine, explained that she thinks of Astraea as a long short story. She wrote it especially for this prize, within two months and for Ali Smith, as it were (she mentioned how formative How to Be Both was for her as a writer). Due to time and word limit constraints, she deliberately crafted a small character arc and didn’t do loads of research, though she had been looking into ships’ surgeons’ journals at the time. She has Irish convict ancestry but noted that this is not uncommon in Tasmania. Astraea is a “sneaky prequel” to her first novel, which has been published in Australia.

Deborah Tomkins

Aerth was originally titled First, Do No Harm, which had the potential to confuse those looking for a medical read. Aerth and Urth are different planets with parallels to our own. The novella tells the story of Magnus, an Everyman on a deeply forested planet heading into an Ice Age. Tomkins first wrote it for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted, then added to it. She initially sent the book to sci-fi publishers but was told it was not ‘sci-fi enough’.

Griffiths remarked that the shortlist was all-female and that the two winners show how a novella can do many different things: Astraea is at the low end of the word count at 22,000 words and takes place over just 36 hours; Aerth is towards the upper limit at 36,000 words and spans about 40 years.

Neil Griffiths

All the panellists dismissed the idea of a hierarchy with the full-length novel at the top. Griffiths said that the constraints of the novella, to need to discard and discard, make it stand out.

A further title from the 2024 shortlist, We Hexed the Moon by Mollyhall Seeley, will also be published by Weatherglass next year, and submissions are now open for the Weatherglass Novella Prize 2025.

Many thanks for my free ticket to a great event. Weatherglass has also kindly offered to send Cathy and me copies of the two novellas to review over the course of #NovNov. I’m looking forward to reading both winners!

Novellas in November 2023: That’s a Wrap!

This was Cathy’s and my fourth year co-hosting Novellas in November. We’ve done our best to keep up with your posts, collected via four Inlinkz post parties. We had 52 bloggers take part this year, contributing a total of 175 posts. You can look back at them all here. See also Cathy’s wrap-up post.

Claire Keegan continued to get lots of love this year, and it was great to see people engaging with our weekly prompts and buddy reads, and cleverly combining challenges with German Lit Month, Nonfiction November and Beryl Bainbridge Reading Week. Other books highlighted more than once included Cheri by Jo Ann Beard, They by Kay Dick, Train Dreams by Denis Johnson and Two Lives by William Trevor.

We’d love to get your feedback about what worked well or less well this month…

- Did you like having the prompts? Or would you rather go back to themes?

- Was it good to have a choice of buddy reads? Or do you prefer having just one?

- Did Inlinkz work okay for hosting the link-up?

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov23! We’ll see you back here next year.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

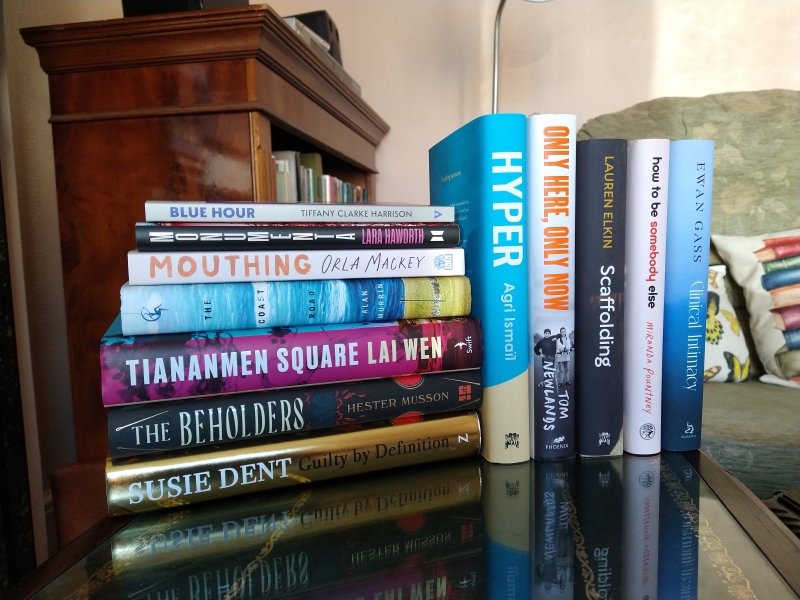

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

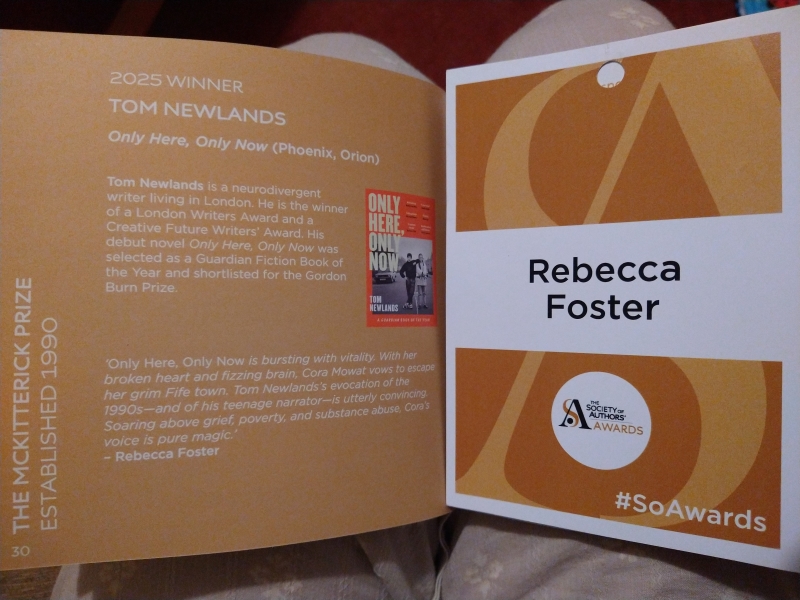

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

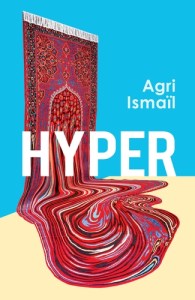

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.”

Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.” Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.

Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]  This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

The Murderer’s Ape

The Murderer’s Ape

My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster: Having become a homeowner for the first time earlier this year, I was interested in how an author would organize their life around the different places they’ve lived. The early chapters about being a child in Carlisle are compelling in terms of cultural history; later on she observes gentrification in London, and her home becomes a haven for her during her cancer treatment.

My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster: Having become a homeowner for the first time earlier this year, I was interested in how an author would organize their life around the different places they’ve lived. The early chapters about being a child in Carlisle are compelling in terms of cultural history; later on she observes gentrification in London, and her home becomes a haven for her during her cancer treatment. Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie: A reread started on our July trip to the Outer Hebrides. I’d forgotten how closely Jamie’s interests align with my own: Scotland and its islands, birds, the prehistoric, museums, archaeology. I particularly appreciated “Three Ways of Looking at St Kilda,” but everything she writes is profound: “if we are to be alive and available for joy and discovery, then it’s as an animal body, available for cancer and infection and pain.”

Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie: A reread started on our July trip to the Outer Hebrides. I’d forgotten how closely Jamie’s interests align with my own: Scotland and its islands, birds, the prehistoric, museums, archaeology. I particularly appreciated “Three Ways of Looking at St Kilda,” but everything she writes is profound: “if we are to be alive and available for joy and discovery, then it’s as an animal body, available for cancer and infection and pain.”

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

for me)

for me)