Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

February Releases by Nick Acheson, Charlotte Eichler and Nona Fernández (#ReadIndies)

Three final selections for Read Indies. I’m pleased to have featured 16 books from independent publishers this month. And how’s this for neat symmetry? I started the month with Chase of the Wild Goose and finish with a literal wild goose chase as Nick Acheson tracks down Norfolk’s flocks in the lockdown winter of 2020–21. Also appearing today are nature- and travel-filled poems and a hybrid memoir about Chilean and family history.

The Meaning of Geese: A thousand miles in search of home by Nick Acheson

I saw Nick Acheson speak at New Networks for Nature 2021 as the ‘anti-’ voice in a debate on ecotourism. He was a wildlife guide in South America and Africa for more than a decade before, waking up to the enormity of the climate crisis, he vowed never to fly again. Now he mostly stays close to home in North Norfolk, where he grew up and where generations of his family have lived and farmed, working for Norfolk Wildlife Trust and appreciating the flora and fauna on his doorstep.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

The Covid-19 lockdowns spawned a number of nature books in the UK – for instance, I’ve also read Goshawk Summer by James Aldred, Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt, The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, and Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss – and although the pandemic is not a major element here, one does get a sense of how Acheson struggled with isolation as well as the normal winter blues and found comfort and purpose in birdwatching.

Tundra bean, taiga bean, brent … I don’t think I’ve seen any of these species – not even pinkfeet, to my recollection – so wished for black-and-white drawings or colour photographs in the book. That’s not to say that Acheson is not successful at painting word pictures of geese; his rich descriptions, full of food-related and sartorial metaphors, are proof of how much he revels in the company of birds. But I suspect this is a book more for birders than for casual nature-watchers like myself. I would have welcomed more autobiographical material, and Wintering by Stephen Rutt seems the more suitable geese book for laymen. Still, I admire Acheson’s fervour: “I watch birds not to add them to a list of species seen; nor to sneer at birds which are not truly wild. I watch them because they are magnificent”.

With thanks to Chelsea Green Publishing for the free copy for review.

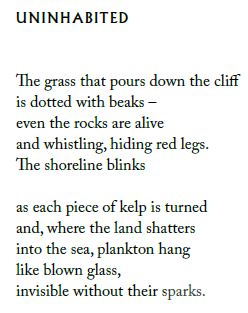

Swimming Between Islands by Charlotte Eichler

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Voyager: Constellations of Memory—A Memoir by Nona Fernández (2019; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer]

Our archive of memories is the closest thing we have to a record of identity. … Disjointed fragments, a pile of mirror shards, a heap of the past. The accumulation is what we’re made of.

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

With thanks to Daunt Books for the free copy for review.

Poetry Review Catch-up: Burch, Carrick-Varty, Davidson, Marya, Parsons (#ReadIndies)

As Read Indies month continues, I’m catching up on poetry collections I’ve been sent by three independent publishers: the UK’s Carcanet Press, and Alice James Books and Terrapin Press, both based in the USA. Various as these five are in style and technique, nature and family ties are linking themes. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

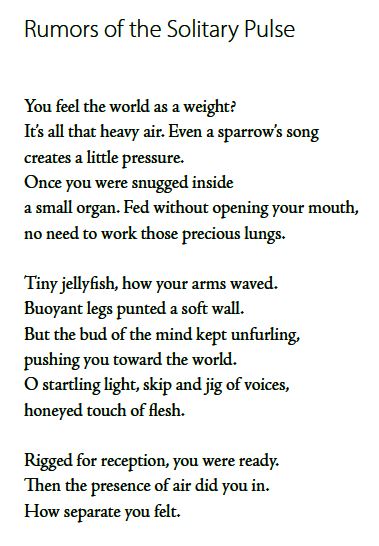

Leave Me a Little Want by Beverly Burch (2022)

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty (2023)

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Arctic Elegies by Peter Davidson (2022)

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Wonderful is the patience of the snow

And glorious the violence of the cold.

How lovely is the power of the dark pole

To draw the iron and move the compass rose.

As cold as loss as cold as freezing steel

In this same vein, I also appreciated the wry “The Museum of Loss” and the ornate “The Mourning Virtuoso.” There’s a bit of an Auden flavour here, but the niche topics didn’t always hold my attention.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

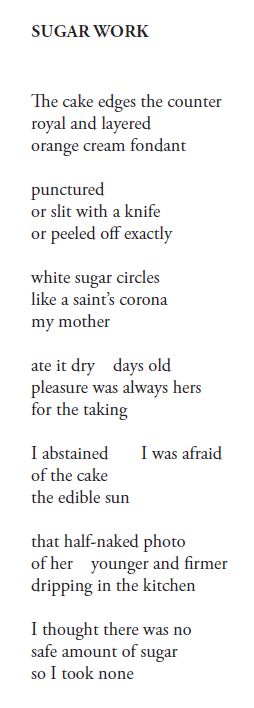

Sugar Work by Katie Marya (2022)

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

With thanks to Alyson Sinclair PR for the free e-copy for review.

The Mayapple Forest by Kim Ports Parsons (2022)

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

Learning How to Be Sad via Books by Susan Cain and Helen Russell

There’s been a lot of sadness in my life over the past few months. If there’s a key lesson I learned from the latest work by these authors, who are among the best self-help writers out there, it’s that denying sadness is the worst thing we could do. Accepting sadness helps us to be compassionate towards others and to acknowledge but ultimately let go of generational pain. There are measures we can take to mitigate sadness – a focus of the second half of Russell’s book – but it can’t be avoided altogether. Alongside the classics of bereavement literature I have been rereading, I found these two books to be valuable companions in grief.

Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole by Susan Cain (2022)

Cain’s Quiet must be one of the best-known nonfiction books of the millennium. It felt like vindication for introverts everywhere. Bittersweet is a little more nebulous in strategy but, boiled down, is a defence of the melancholic personality, one of the types identified by Aristotle (also explored in Richard Holloway’s The Heart of Things). Sadness is not the same as clinical depression, Cain rushes to clarify, though the two might coexist. Melancholy is often associated with creativity and sensitivity, and can lead us into empathy for others. Suffering and death seem like things to flee, but if we sit with them, we will truly be part of the human race and, per the “wounded healer” archetype, may also work toward restoration.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

A love for minor-key music, especially songs by Leonard Cohen, is what initially drew Cain to this topic, but there are other autobiographical seeds: the deaths of many ancestors, including her rabbi grandfather’s entire family, in the Holocaust; her difficult relationship with her controlling mother, who now has dementia; and the deaths from Covid of both her brother, a hospital doctor, and her elderly father in 2020.

Through interviews and attendance at conferences and other events, she draws in various side topics, like the longing that prompts mysticism (Kabbalah and Sufism), loving-kindness meditation, an American culture of positivity that demands “effortless perfection,” ways the business world could cultivate empathy, and how knowledge of death makes life precious. (The only chapter I found less than essential was one about transhumance – the hope of escaping death altogether. Mark O’Connell has that topic covered.) Cain weaves together her research with autobiographical material naturally. As a shy introvert with melancholy tendencies, I found both Quiet and Bittersweet comforting.

With thanks to Viking (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

How to Be Sad: The Key to a Happier Life by Helen Russell (2021)

A reread, though I only skimmed the first time around – my tiny points of criticism would be that the book is a tad long – the print in the paperback is really rather small – and retreads some of the same ground as Leap Year (e.g., how exercise and culture can contribute to a sense of wellbeing). I read that just last year, after enjoying The Year of Living Danishly with my book club. She’s a reliable nonfiction author; I’d liken her to a funnier Gretchen Rubin.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

Russell has an appealingly self-deprecating style and breezily highlights statistics alongside personal anecdotes. Here she faces sources of sadness in her life head-on: her younger sister’s death from SIDS and the silence that surrounded that loss; her parents’ divorce and her sense of being abandoned by her father; struggles with eating disorders and alcohol and exercise addiction; and relationship trials, from changing herself to please boyfriends to undergoing IVF with her husband, T (aka “Legoman”), and adjusting to life as a mother of three.

As in her other self-help work, she interviews lots of experts and people who have gone through similar things to understand why we’re sad and what to do about it. I particularly appreciated chapters on “arrival fallacy” and “summit syndrome,” both of which refer to a feeling of letdown after we achieve what we think will make us happy, whether that be parenthood or the South Pole. Better to have intrinsic goals than external ones, Russell learns.

She also considers cultural differences in how we approach sadness: for instance, Russians relish sadness and teach their children to do the same, whereas the English, especially men, are expected to bury their feelings. Russell notes a waning of the rituals that could help us cope with loss, and a rise in unhealthy coping mechanisms. Like Cain, she also covers sad music (vs. one of her interviewees prescribing Jack Johnson as a mood equalizer). There are lots of laughs to be had, but the epilogue can’t fail to bring a tear to the eye. (Public library)

Both:

I found this quote from the Russell a handy summary of both authors’ premise. Dr Lucy Johnstone says:

“The key question when encountering someone with mental or emotional distress shouldn’t be, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ but rather, ‘What’s happened to you?’”

Suffering is coming for all of us, so why not arm yourself to deal with it and help others through? That’s always been one of my motivations for reading widely: to understand other people’s situations and prepare myself for what the future holds.

Could you see yourself reading a book about sadness?

The Swedish Art of Ageing Well by Margareta Magnusson (#NordicFINDS23)

Annabel’s Nordic FINDS challenge is running for the second time this month. I hope to manage at least one more read for it; this one feels like a cheat as it’s not exactly in translation. Magnusson, who is Swedish, either wrote it in English or translated it herself for simultaneous 2022 publication in Sweden and the USA – where the title phrase was “Aging Exuberantly.” There is some quirky phrasing that a native speaker would never use, more so than in her Döstädning: The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning, which I reviewed last year, but it’s perfectly understandable.

The subtitle is “Life wisdom from someone who will (probably) die before you,” which gives a flavour of 89-year-old Magnusson’s self-deprecating sense of humour. The big 4-0 is coming up for me later this year, but I’ve been reading books about ageing and death since my twenties and find them valuable for gaining perspective and storing up wisdom.

This is not one of those “hygge” books extolling the virtues of Scandinavian culture, but rather a charming self-help memoir recounting what the author has learned about what matters in life and how to gracefully accept the ageing process. Each chapter is like a mini essay with a piece of advice as the title. Some are more serious than others: “Don’t Fall Over” and “Keep an Open Mind” vs. “Eat Chocolate” and “Wear Stripes.”

Since Magnusson was widowed, she has valued her friendships all the more, and during the pandemic cheerfully switched to video chats (G&T in hand) with her best friend since age eight. She is sweetly optimistic despite news headlines; after all, in the words of one of her chapter titles, “The World Is Always Ending” – she grew up during World War II and remembers the bad old days of the Cold War and personal near-tragedies like when the ship on which her teenage son was a deckhand temporarily disappeared in the South China Sea.

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Volunteering, spending lots of time with younger people, looking after another living thing (a houseplant if you can’t commit to a pet), turning daily burdens into beloved routines, and keeping your hair looking as nice as possible are some of Magnusson’s top tips for coping.

An appendix gives additional death-cleaning guidance based on Covid-era FAQs; the chapter in this book that is most reminiscent of the practical approach of Döstädning is “Don’t Leave Empty-Handed,” which might sound metaphorical but in fact is a literal mantra she learned from an acquaintance. On a small scale, it might mean tidying a room gradually by picking up at least one item each time you pass through; more generally, it could refer to a mindset of cleaning up after oneself so that the world is a better place for one’s presence.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

September Releases by John Clegg & Tom Gauld (Lots More to Come!)

There aren’t enough hours in the day, or days left in this month, to write up all the terrific September releases I’ve read. The nonfiction fell into two broad thematic camps: books about books (Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell and Blurb Your Enthusiasm by Louise Willder still to come), or books about death (What Remains? by Rupert Callender, And Finally by Henry Marsh, and Sinkhole by Juliet Patterson still to come). However, I’ll start off with the two I happen to have written about so far, which are (the odd one out) poetry about science and watery travel, and bookish cartoons. Both:

Aliquot by John Clegg

This is the second Carcanet collection by the London bookseller. An aliquot is a sample, a part that represents the whole; a scientific counterpart to synecdoche. It’s a perfect word for what poetry can do: point at larger truths through the pinpricks of meaning found in the everyday. The title poem juxtaposes two moments where the poet muses on the part/whole dichotomy: watching a catering school student and teacher transferring peas from one container to another and spotting two cellists on a tube train. Drawn in by detail, we observe the inevitable movement from separation to togetherness.

This is the second Carcanet collection by the London bookseller. An aliquot is a sample, a part that represents the whole; a scientific counterpart to synecdoche. It’s a perfect word for what poetry can do: point at larger truths through the pinpricks of meaning found in the everyday. The title poem juxtaposes two moments where the poet muses on the part/whole dichotomy: watching a catering school student and teacher transferring peas from one container to another and spotting two cellists on a tube train. Drawn in by detail, we observe the inevitable movement from separation to togetherness.

A high point is “A Gene Sequence,” about an administrator working behind the scenes at a genomics conference on a Cambridge campus: each poem is named after a different amino acid and the lines (sometimes with the help of extreme enjambment) always begin with the arrangement of A, C, G, and T that encodes them. Here’s an example:

Much of the imagery is maritime, with the occasional reference to a desert (“Language as Sonora”) or settlement (“Dormer Windows” and “Quebec City”). The locations include a science campus and a storm-threatened hotel (“Hurricane Joaquin,” one of my favourites). A proverb is described as being as potent as a raw onion. Here’s a lynx you’ll never see – but she will see you. Like in a Caroline Bird collection, there’s many an absurd or imagined situation. The vocabulary is unusual, sometimes lofty: “their cursory repertoire of query.” Alliteration teems, as in “The High Lama Explains How Items Are Procured for Shangri-La.” Overall, a noteworthy and unique collection that I’d recommend.

A favourite, apropos of nothing stanza from “Lucan – The Waterline”:

There is a kind of crab known to devour human flesh.

There is a shelf five storeys undersea

Where small yachts pile up like bric-a-brac.

There is a town in Maryland called Alibi.

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

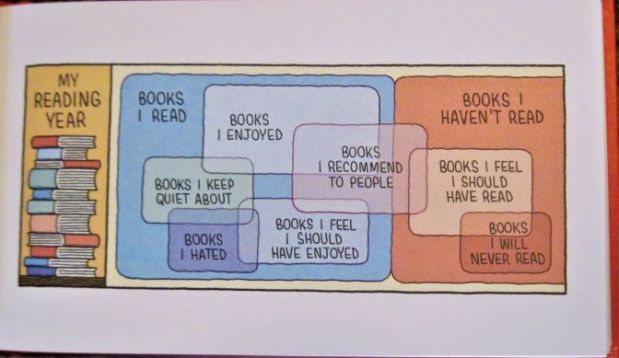

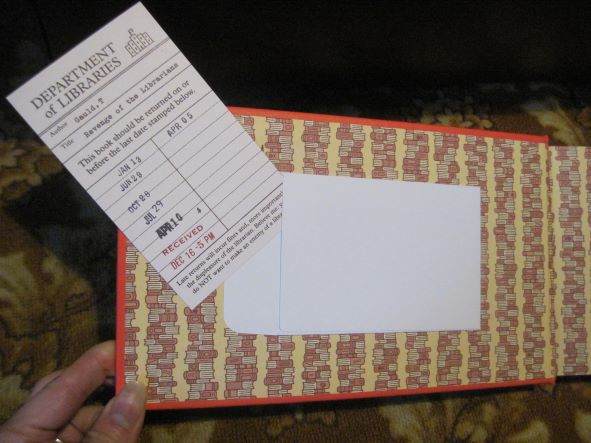

Revenge of the Librarians by Tom Gauld

You have probably seen Gauld’s cartoons in the Guardian, New Scientist or New Yorker. I’ve saved clippings of my favourite bookish ones over the years. They’re full of literary in-jokes and bibliophile problems, and divided about equally between a writer’s perspective and a reader’s: the struggle for inspiration and novelty on the one hand, and the battle with the TBR and the impulse to read what one feels one should versus what one enjoys on the other. He pokes holes in the pretensions on either side. Jane Austen features frequently.

Gauld’s figures are usually blocky stick figures without complete facial features (or books or ghosts), and he often makes use of multiple choice and choose your own adventure structures. Elsewhere he plays around with book titles and typical plots, or stages mild-mannered arguments between authors and their editors or publicists, who generally have quite different notions of quality and marketability.

Lest you dismiss cartoons as being out of touch, the effect of the pandemic on bookshops, libraries and literary events is mentioned a few times. Librarians are depicted as old-time gangsters peddling books while their buildings are closed: “Overdue books are dealt with swiftly and mercilessly” it reads under a panel of a fedora-wearing, revolver-toting figure warning, “The boss says if you ain’t finished ‘The Mirror and the Light’ by tomorrow, it’s curtains!”

Some more favourite lines:

- “1903: Henry James writes a sentence so long and circuitous that he becomes lost inside it for three days.”

- (says one pigeon to another) “I’ve become a psychogeographer. It’s mainly walking around disapproving of gentrification.”

- “A horrible feeling crept over Elaine that perhaps the problems with her novel couldn’t be overcome by changing the font.”

Two spreads that are too good not to share in full (I feel seen!):

And would you look at this attention to detail on the inside cover!

This is destined for many a book-lover’s Christmas stocking.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating. Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

In April 2020, McHugh experienced a relapse of MS so bad she had to move back in with her parents and was sleeping 20 hours a day. Her sphere had contracted to a single room. If only, she wished, there was “something to concentrate on that wasn’t my unravelling body or the unravelling world.” A Catholic upbringing and childhood holidays in Northumberland made her think about the early Christian hermits and saints like Aidan, Cuthbert and Julian of Norwich who salvaged something from solitude, who out of the privations of monasticism made monuments of faith and, sometimes, written documents, too.

In April 2020, McHugh experienced a relapse of MS so bad she had to move back in with her parents and was sleeping 20 hours a day. Her sphere had contracted to a single room. If only, she wished, there was “something to concentrate on that wasn’t my unravelling body or the unravelling world.” A Catholic upbringing and childhood holidays in Northumberland made her think about the early Christian hermits and saints like Aidan, Cuthbert and Julian of Norwich who salvaged something from solitude, who out of the privations of monasticism made monuments of faith and, sometimes, written documents, too.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit. A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one.

A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one. Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his.

Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his. Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling.

Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling. Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement. Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.

Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant. This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.” The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head. Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in