Literary Wives Club: The Sentence by Louise Erdrich

This has been my first read with the Literary Wives online book club. The other members will also be posting their thoughts this week; we consider four books per year in total.

See also the reviews by:

Kay at What Me Read

Lynn at Smoke & Mirrors

Naomi at Consumed by Ink

I wrote a general review of The Sentence in April when it was on the Women’s Prize longlist (it has since advanced to the shortlist). This time I’m focusing on the relationship between Tookie and Pollux. The central question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

~SPOILERS IN THIS ONE~

~SPOILERS IN THIS ONE~

There are some unusual aspects to the central marriage in this novel. For one thing, Pollux, a former tribal policeman, was the one to arrest Tookie. For another, although he is a “ceremony man” keeping up Native American rituals (e.g., burning sweetgrass and receiving an eagle corpse from the government to make a fan), he doesn’t believe in ghosts, so Tookie keeps Flora’s haunting of the bookshop from him, as well as from some of her colleagues. For a time, this secret makes Tookie feel like she’s facing the supernatural alone.

Pollux does not, cumulatively, get a lot of page time in the novel, yet I got the sense that he was always there in the background as support. Their relationship is casual and sweet, with lots of banter and a good dollop of sex considering they’re some way into middle age. Clearly, they rely on each other. Their marriage keeps Tookie grounded even when traumatic memories or awful current events rear up.

Now I live as a person with a regular life. A job with regular hours after which I come home to a regular husband. … I live the way a person does who has ceased to dread each day’s ration of time. I live what can be called a normal life only if you’ve always expected to live such a way. If you think you have the right. Work. Love. Food. A bedroom sheltered by a pine tree. Sex and wine.

The thing I knew was that if anything happened to Pollux I would die too. I would be happy to die. I would make sure that I did.

With the latter passage in mind, I did fear the worst when Pollux caught Covid and was hospitalized; I was as relieved as Tookie when he was discharged.

Along with Pollux comes his daughter, Hetta, and her baby son Jarvis. Tookie and Hetta had generally been cool towards each other, but the presence of the baby and the lockdown situation soften things between them. Having never been a maternal sort, Tookie falls completely in love with Jarvis and takes every excuse to babysit him. This gives us a welcome glimpse into another aspect of her character.

I noted a couple of other passages where rituals have practical or metaphorical significance for the central relationship:

At a New Year’s buffet: “a wild rice argument can wreck friendships, kill marriages, if allowed to rage.”

“You let the logs burn long enough so they made a space between them. You gotta keep the fire new. Every piece of wood needs a companion to keep it burning. Now push them together. Not too much. They also need that air. Get them close, but not on top of each other. Just a light connection all the way along. Now you’ll see a row of even flames.”

Pollux is literally instructing Tookie in how to light a fire there, but could just as well be prescribing what makes a marriage work. Connection but a bit of distance; support plus freedom. Their existence as a couple seems to achieve that. They have their individual lives with separate jobs and hobbies, but also a cosy bond that buoys them.

Next book: Red Island House by Andrea Lee in September.

January 2022 Releases, Part I: Jami Attenberg and Roopa Farooki

It’s been a big month for new releases! I’m still working on a handful and will report back on two batches of three, tomorrow and Sunday; more will likely turn up in review roundups in future months. For today, I have a memoir in essays about a peripatetic writer’s life and an excerpt from my review of a junior doctor’s chronicle of the early days of the pandemic.

I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home by Jami Attenberg

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

Along with nomadism, creativity and being a woman are key themes. Attenberg notices how she’s treated differently from male writers at literary events, and sometimes has to counter antifeminist perspectives even from women – as in a bizarre debate she ended up taking part in at a festival in Portugal. She takes risks and gets hurt, physically and emotionally. Break-ups sting, but she moves on and tries to be a better person. There are a lot of hard-hitting one-liners about the writing life and learning to be comfortable in one’s (middle-aged) body:

I believe that one must arrive at an intersection of hunger and fear to make great art.

Who was I hiding from? I was only ever going to be me. I was only ever going to have this body forever. Life was too short not to have radical acceptance of my body.

Whenever my life turns into any kind of cliché, I am furious. Not me, I want to scream. Not me, I am special and unusual. But none of us are special and unusual. Our stories are all the same. It is just how you tell them that makes them worth hearing again.

I did not know yet how books would save me over and over again. I did not know that a book was a reason to live. I did not know that being alive was a reason to live.

Late on comes her #MeToo story, which in some ways feels like the core of the book. When she was in college, a creative writing classmate assaulted her on campus while drunk. She reported it but nothing was ever done; it only led to rumours and meanness towards her, and a year later she attempted suicide. You know how people will walk into a doctor’s appointment and discuss three random things, then casually drop in a fourth that is actually their overriding concern? I felt that way about this episode: that really the assault was what Attenberg wanted to talk about, and could have devoted much more of the book to.

The chapters are more like mini essays, flitting between locations and experiences in the same way she has done, and sometimes repeating incidents. I think the intent was to mimic, and embrace, the random shape that a life takes. Each vignette is like a competently crafted magazine piece, but the whole is no more than the sum of the parts.

With thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the proof copy for review.

Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

A great addition to my Covid chronicles repertoire!

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Would one of these books interest you?

These Precious Days by Ann Patchett

I consider myself an Ann Patchett fan, having read eight of her books by now. Although she’s better known for her novels, I have a slight preference for her nonfiction – Truth and Beauty, her memoir of her friendship with Lucy Grealy; and her two collections of autobiographical essays, This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage and now These Precious Days, which made it onto my Best of 2021 list last month. Compared to the previous volume, the essays here, though no less sincere and thoughtful, are more melancholy. The preoccupation with death and drive to simplify life (“My Year of No Shopping,” “How to Practice”) seem appropriate for Covid times.

The opening essay, “Three Fathers,” gives wry portraits of her father and her two stepfathers, contrasting their careers, her relationship with each, and their deaths. In a final piece before the epilogue, she notes the bittersweet privilege of her membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters – new members are only inducted to replace senior ones, for each of whom she receives a death notice in the mail. Memento mori are everywhere; “The human impulse is to look for order, but there isn’t any. People come and go. When you try to find your place among all the living and dead, the numbers are unmanageable.”

The long title essay, first published in Harper’s, is about her stranger-than-fiction friendship with Tom Hanks’s personal assistant, Sooki Raphael (her painting of Patchett’s dog Sparky adorns the cover). They first made contact after Patchett read an early copy of Hanks’s short story collection, gave it a nice endorsement, and then interviewed him at the D.C. stop on his book tour. Sooki had recurrent pancreatic cancer; Patchett’s husband Karl, a doctor, got her into a medical trial in Nashville and she lived with them throughout her treatment, including during Covid. There are so many twists to this story, so many moments when it might have faltered. Patchett is well aware of the unlikelihood and uses it to comment on her own plots, and the fact that sometimes what she thinks a novel is about ends up being far from the truth.

Patchett also expresses her appreciation of other authors (“Eudora Welty, an introduction,” “Reading Kate DiCamillo”), looks back to her young adulthood (“The First Thanksgiving,” “The Paris Tattoo”) and explores her other key relationships: her ever-youthful mother is the subject of “Sisters,” she celebrates a childhood friend in “Tavia,” and her worry over her 16-years-older husband fuels “Flight Plan” (about his amateur pilot hobby) and “The Moment Nothing Changed” (about his heart attack scare). Many of the shorter pieces first appeared in other publications or anthologies; a few verge on throwaway if I’m being harsh (did we need the essays on Snoopy and knitting?).

But it’s the approach that distinguishes the work as a whole: a clear eye on herself and others; honesty and deep emotion that never tip into mawkishness. I also enjoyed the little glimpses into her everyday domestic life, as well as her work behind the scenes at Parnassus Books. The one essay that meant the most to me, though, was “There Are No Children Here,” which matter-of-factly covers everything I’d ever like to say or hear about childlessness. At their best, Patchett’s books are not just pleasant reads but fond companions on the journey of life, and that’s how I felt about this one. (Susan included it on her list of comfort reading, too.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

It was

It was

I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close.

I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close.

These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad.

These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad. Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives.

Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives.

Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.”

Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.” Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.”

Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.” The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community.

The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community. less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro.

less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro. The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym). Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022) Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with  It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

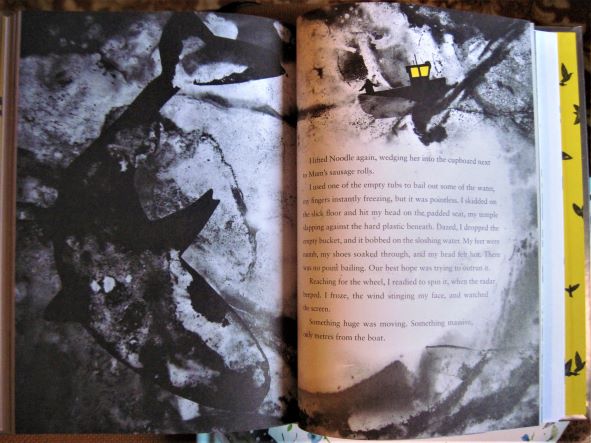

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir  Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties.

Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties. What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like

The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.  Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).

Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.