Literary Wives Club: The Harpy by Megan Hunter

(My fifth read with the Literary Wives online book club; see also Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews.)

Megan Hunter’s second novella, The Harpy (2020), treads familiar ground – a wife discovers evidence of her husband’s affair and questions everything about their life together – but somehow manages to feel fresh because of the mythological allusions and the hint of how female rage might reverse familial patterns of abuse.

Lucy Stevenson is a mother of two whose husband Jake works at a university. One day she opens a voicemail message on her phone from a David Holmes, saying that he thinks Jake is having an affair with his wife, Vanessa. Lucy vaguely remembers meeting the fiftysomething couple, colleagues of Jake’s, at the Christmas party she hosted the year before.

As further confirmation arrives and Lucy tries to carry on with everyday life (another Christmas party, a pirate-themed birthday party for their younger son), she feels herself transforming into a wrathful, ravenous creature – much like the harpies she was obsessed with as a child and as a Classics student before she gave up on her PhD.

Like the mythical harpy, Lucy administers punishment. At first, it’s something of a joke between her and Jake: he offers that she can ritually harm him three times. Twice it takes physical form; once it’s more about reputational damage. The third time, it goes farther than either of them expected. It’s clever how Hunter presents this formalized violence as an inversion of the domestic abuse of which Lucy’s mother was a victim.

Lucy also expresses anger at how women are objectified, and compares three female generations of her family in terms of how housewifely duties were embraced or rejected. She likens the grief she feels over her crumbling marriage to contractions or menstrual cramps. It’s overall a very female text, in the vein of A Ghost in the Throat. You feel that there’s a solidarity across time and space of wronged women getting their own back. I enjoyed this so much more than Hunter’s debut, The End We Start From. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

“Marriage and motherhood are like death … no one comes back unchanged.”

So much in life can remain unspoken, even in a relationship as intimate as a marriage. What becomes routine can cover over any number of secrets; hurts can be harboured until they fuel revenge. Lucy has lost her separate identity outside of her family relationships and needs to claw back a sense of self.

I don’t know that this book said much that is original about infidelity, but I sympathized with Lucy’s predicament. The literary and magical touches obscure the facts of the ending, so it’s unclear whether she’ll stay with Jake or not. Because we’re mired in her perspective, it’s hard to see Jake or Vanessa clearly. Our only choice is to side with Lucy.

Next book: Sea Wife by Amity Gaige in September

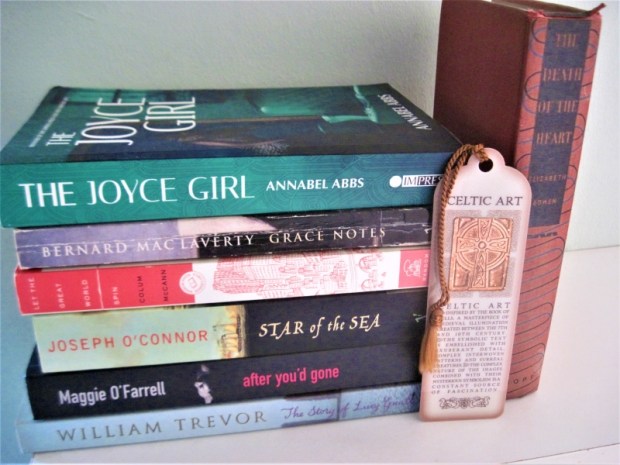

The Beginning of Spring with Penelope Fitzgerald & Karl Ove Knausgaard

(From To Star the Dark by Doireann Ní Ghríofa)

Reading with the seasons is one way I mark time. This is the first of two, or maybe three, batches of spring reading for me this year. The daffodils have already gone over; bluebells and peonies are coming out; and all the trees, including the two wee apple trees we’ve planted at our new house, are sprouting hopeful buds.

The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald (1988)

My fourth from Fitzgerald. One of her later novels, this was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Its pre-war Moscow setting seemed to take on extra significance as I read it during the early weeks of the Russian occupation of Ukraine. Its title is both literal, referring to the March days in 1913 when “there was the smell of green grass and leaves, inconceivable for the last five months” and the expatriate Reid family can go to their dacha once again, and metaphorical. For what seems to printer Frank Reid – whose wife Nellie has taken a train back to England and left him to raise their three children alone – like an ending may actually presage new possibilities when his accountant, Selwyn, hires a new nanny for the children.

My fourth from Fitzgerald. One of her later novels, this was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Its pre-war Moscow setting seemed to take on extra significance as I read it during the early weeks of the Russian occupation of Ukraine. Its title is both literal, referring to the March days in 1913 when “there was the smell of green grass and leaves, inconceivable for the last five months” and the expatriate Reid family can go to their dacha once again, and metaphorical. For what seems to printer Frank Reid – whose wife Nellie has taken a train back to England and left him to raise their three children alone – like an ending may actually presage new possibilities when his accountant, Selwyn, hires a new nanny for the children.

I have previously found Fitzgerald’s work slight, subtle to the point of sailing over my consciousness without leaving a ripple. While her characters and scenes still underwhelm – I always want to go deeper – I liked this better than the others I’ve read (The Bookshop, Offshore, and The Blue Flower), perhaps simply because it’s not a novella so is that little bit more expansive. And though she’s not an author you’d turn to for plot, more does actually happen here, including a gunshot. Frank is a genial Everyman, fond of Russia yet exasperated with its bureaucracy and corruption – this “magnificent and ramshackle country.” He knows how things work and isn’t above giving a bribe when it’s expedient for his business:

He took an envelope out of his drawer, and, conscious of taking only a mild risk, since the whole unwieldy administration of All the Russias, which kept working, even if only just, depended on the passing of countless numbers of such envelopes, he slid it across the top of the desk. The inspector opened it without embarrassment, counted out the three hundred roubles it contained and transferred them to a leather container, half way between a wallet and a purse, which he kept for ‘innocent income’.

I particularly liked Uncle Charlie’s visit, the glimpses of Orthodox Easter rituals, and a strangely mystical moment of communion with some birch trees. A part of me did wonder if the setting was neither here nor there, if a few plastered-on descriptions of Moscow were truly enough to constitute convincing historical fiction. That’s a question for those more familiar with Russia and its literature to answer, but I enjoyed the seasonal awakening. (Secondhand, charity shop in Bath)

Spring by Karl Ove Knausgaard (2016; 2018)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Ingvild Burkey; illustrated by Anna Bjerger]

Knausgaard is a repeat presence in my seasonal posts: I’ve also reviewed Autumn, Winter and Summer. I read his quartet out of order, finishing with the one that was published third. The project was conceived as a way to welcome his fourth child, Anna, into the world. Whereas the other books prioritize didactic essays on seasonal experiences, this is closer in format to Knausgaard’s granular autofiction: the throughline is a journey through an average day with his baby girl, from when she wakes him before 6 a.m. to a Walpurgis night celebration (“the evening when spring is welcomed in with song in Sweden”). They see the other kids off to school, then make a disastrous visit to a mental hospital – he forgets his bank card and ID, the baby’s bottle, everything, and has to beg cash from his bank to buy petrol to get home.

Knausgaard is a repeat presence in my seasonal posts: I’ve also reviewed Autumn, Winter and Summer. I read his quartet out of order, finishing with the one that was published third. The project was conceived as a way to welcome his fourth child, Anna, into the world. Whereas the other books prioritize didactic essays on seasonal experiences, this is closer in format to Knausgaard’s granular autofiction: the throughline is a journey through an average day with his baby girl, from when she wakes him before 6 a.m. to a Walpurgis night celebration (“the evening when spring is welcomed in with song in Sweden”). They see the other kids off to school, then make a disastrous visit to a mental hospital – he forgets his bank card and ID, the baby’s bottle, everything, and has to beg cash from his bank to buy petrol to get home.

Looming over the circadian narrative is his wife’s mental health crisis the summer before (his ex-wife Linda Boström Knausgård, a writer in her own right, has bipolar disorder), while she was pregnant with Anna, and the repercussions it has had for their family. Other elements echo those of the previous books: the formation of memories, to what extent his personality is fixed, whether he’s fated to turn into his father, minor health concerns, and so on. Although this volume is less aphoristic than the previous books, there are still moments when he muses on life and gives general advice:

Self-deception is perhaps the most human thing of all. … And perhaps the following is nothing but self-deception: the easy life is nothing to aspire to, the easy choice is never the worthiest solution, only the difficult life is a life worth living. I don’t know. But I think that’s how it is. What would seem to contradict this, is that I wish you and your siblings simple, easy, long and happy lives. … The advantage of having siblings is that it is a lifelong attachment, and that nothing can break it.

All in all, this was the highlight of the series for me. Each of the four is illustrated by a different contemporary artist. Bjerger is less abstract than some of the others, which I count as a plus. (New bargain/remainder copy, Minster Gate Bookshop, York)

This daffodil bookmark was embroidered by local textile artist Christine Highnett. My mother bought it for me from Sandham Memorial Chapel’s gift shop last summer.

A favourite random moment: A creeper coming through the tile roof of his office pushes a book off the shelf. It’s American Psycho. “I still found it incredible. And a little frightening, the blind force of growth”.

Speaking of meaningful, or perhaps ironic, timing: He records a conversation with his neighbour, who was mansplaining about Russian aggression and the place of Ukraine: “Kiev was the first great city in what became the Russian empire. … The Ukraine and Russia are like twins. … They belong together. At least the Russians see it that way. … The very idea of Russia is imperialistic.”

Any spring reads on your plate?

Recent Literary Awards & Online Events: Folio Prize and Claire Fuller

Literary prize season is in full swing! The Women’s Prize longlist, revealed on the 10th, contained its usual mixture of the predictable and the unexpected. I correctly predicted six of the nominees, and happened to have already read seven of them, including Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (more on this below). I’m currently reading another from the longlist, Luster by Raven Leilani, and I have four on order from the library. There are only four that I don’t plan to read, so I’ll be in a fairly good place to predict the shortlist (due out on April 28th). Laura and Rachel wrote detailed reaction posts on which there has been much chat.

Rathbones Folio Prize

This year I read almost the entire Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist because I was lucky enough to be sent the whole list to feature on my blog. The winner, which the Rathbones CEO said would stand as the “best work of literature for the year” out of 80 nominees, was announced on Wednesday in a very nicely put together half-hour online ceremony hosted by Razia Iqbal from the British Library. The Folio scheme also supports writers at all stages of their careers via a mentorship scheme.

It was fun to listen in as the three judges discussed their experience. “Now nonfiction to me seems like rock ‘n’ roll,” Roger Robinson said, “far more innovative than fiction and poetry.” (Though Sinéad Gleeson and Jon McGregor then stood up for the poetry and fiction, respectively.) But I think that was my first clue that the night was going to go as I’d hoped. McGregor spoke of the delight of getting “to read above the categories, looking for freshness, for excitement.” Gleeson said that in the end they had to choose “the book that moved us, that enthralled us.”

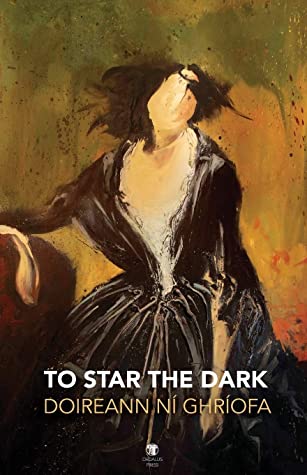

All eight authors had recorded short interview clips about their experience of lockdown and how they experiment with genre and form, and seven (all but Doireann Ní Ghríofa) were on screen for the live announcement. The winner of the £30,000 prize, author of an “exceptional, important” book and teller of “a story that had to be told,” was Carmen Maria Machado for In the Dream House. I was delighted with this result: it was my first choice and is one of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve read. I remember reading it on my Kindle on the way to and from Hungerford for a bookshop event in early March 2020 – my last live event and last train ride in over a year and counting, which only made the reading experience more memorable.

I like what McGregor had to say about the book in the media release: “In the Dream House has changed me – expanded me – as a reader and a person, and I’m not sure how much more we can ask of the books that we choose to celebrate.”

There are now only two previous Folio winners that I haven’t read, the memoir The Return by Hisham Matar and the novel Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, so I’d like to get those two out from the library soon and complete the set.

Other literary prizes

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

I also tuned into the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards ceremony (on YouTube), which was unfortunately marred by sound issues. This year’s three awards went to women: Dervla Murphy (Edward Stanford Outstanding Contribution to Travel Writing), Anita King (Bradt Travel Guides New Travel Writer of the Year; you can read her personal piece on Syria here), and Taran N. Khan for Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul (Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year in association with the Authors’ Club).

Other prize races currently in progress that are worth keeping an eye on:

- The Jhalak Prize for writers of colour in Britain (I’ve read four from the longlist and would be interested in several others if I could get hold of them)

- The Republic of Consciousness Prize for work from small presses (I’ve read two; Doireann Ní Ghríofa gets another chance – fingers crossed for her)

- The Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction (next up for me: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, to review for BookBrowse)

Claire Fuller

Yesterday evening, I attended the digital book launch for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (my review will be coming soon). I’ve read all four of her novels and count her among my favorite contemporary writers. I spotted Eric Anderson and Ella Berthoud among the 200+ attendees, and Claire’s agent quoted from Susan’s review – “A new novel from Fuller is always something to celebrate”! Claire read a passage from the start of the novel that introduces the characters just as Dot starts to feel unwell. Uniquely for online events I’ve attended, we got a tour of the author’s writing room, with Alan the (female) cat asleep on the daybed behind her, and her librarian husband Tim helped keep an eye on the chat.

After each novel, as a treat to self, she buys a piece of art. This time, she commissioned a ceramic plate from Sophie Wilson with lines and images from the book painted on it. Live music was provided by her son Henry Ayling, who played acoustic guitar and sang “We Roamed through the Garden,” which, along with traditional folk song “Polly Vaughn,” are quoted in the novel and were Claire’s earworms for two years. There was also a competition to win a chocolate Easter egg, given to whoever came closest to guessing the length of the new novel in words. (It was somewhere around 89,000.)

Good news – she’s over halfway through Book 5!

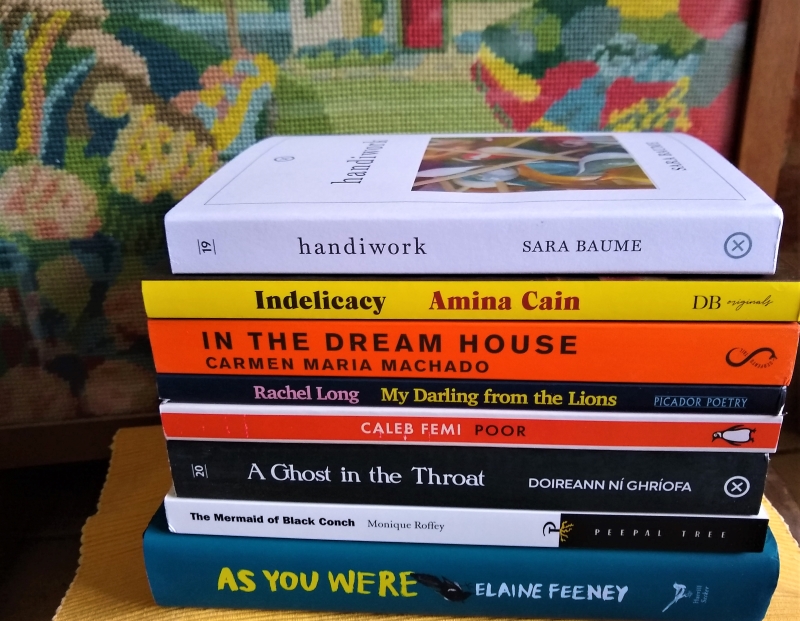

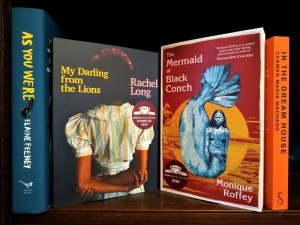

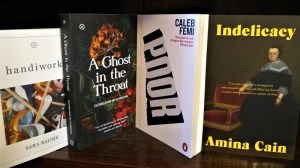

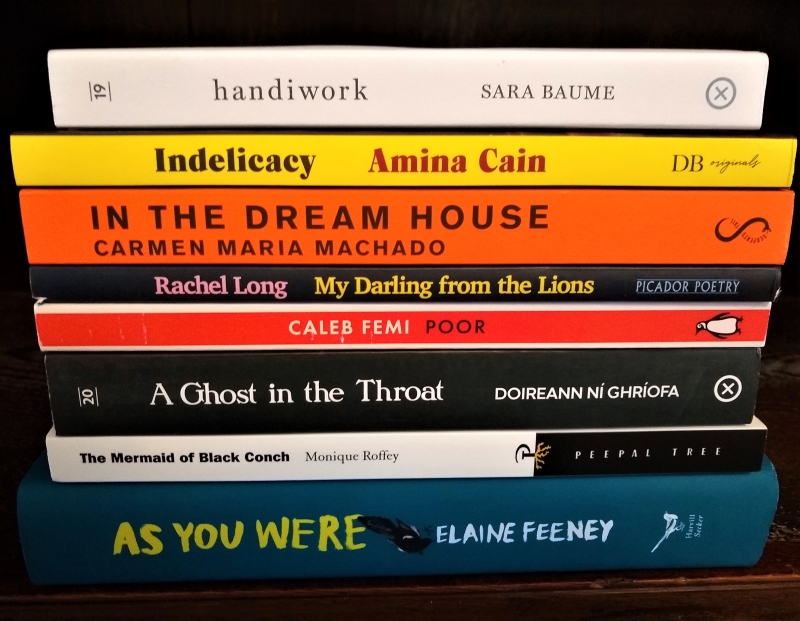

Rathbones Folio Prize 2021 Shortlist Reviews & Prediction

I’ve nearly managed to read the whole Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist before the prize is announced on the evening of Wednesday the 24th. (You can sign up to watch the online ceremony here.) I reviewed the Baume and Ní Ghríofa as part of a Reading Ireland Month post on Saturday, and I’d reviewed the Machado last year in a feature on out-of-the-ordinary memoirs. This left another five books. Because they were short, I’ve been able to read and/or review another four over the past couple of weeks. (The only one unread is As You Were by Elaine Feeney, which I made a false start on last year and didn’t get a chance to try again.)

Nominations come from the Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, so the shortlisted authors have been chosen by an audience of their peers. Indeed, I kept spotting judges’ or fellow nominees’ names in the books’ acknowledgements or blurbs. I tried to think about the eight as a whole and generalize about what the judges were impressed by. This was difficult for such a varied set of books, but I picked out two unifying factors: A distinctive voice, often with a musicality of language – even the books that don’t include poetry per se are attentive to word choice; and timeliness of theme yet timelessness of experience.

Poor by Caleb Femi

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

The Story of Ruthless

Anyone smart enough

to study the food chain

of the estate knew exactly

who this warrior girl was;

once she lined eight boys

up against a wall,

emptied their pockets.

Nobody laughed at the boys.

Another that stood out for me was the two-part “A Designer Talks of Home / A Resident Talks of Home,” a found poem partially constructed from dialogue from a Netflix documentary on interior design. It ironically contrasts airy aesthetic notions with survival in a concrete wasteland. If you loved Surge by Jay Bernard, this should be next on your list.

My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

The novella belongs to no specific time or place; while Cain lives in Los Angeles, this most closely resembles ‘wan husks’ of European autofiction in translation. Vitória issues pretentious statements as flat as the painting style she claims to love. Some are so ridiculous they end up being (perhaps unintentionally) funny: “We weren’t different from the cucumber, the melon, the lettuce, the apple. Not really.” The book’s most extraordinary passage is her husband’s rambling, defensive monologue, which includes the lines “You’re like an old piece of pie I can’t throw away, a very good pie. But I rescued you.”

It seems this has been received as a feminist story, a cheeky parable of what happens when a woman needs a room of her own but is trapped by her social class. When I read in the Acknowledgements that Cain took lines and character names from Octavia E. Butler, Jean Genet, Clarice Lispector, and Jean Rhys, I felt cheated, as if the author had been engaged in a self-indulgent writing exercise. This was the shortlisted book I was most excited to read, yet ended up being the biggest disappointment.

On the whole, the Folio shortlist ended up not being particularly to my taste this year, but I can, at least to an extent, appreciate why these eight books were considered worthy of celebration. The authors are “writers’ writers” for sure, though in some cases that means they may fail to connect with readers. There was, however, some crossover this year with some more populist prizes like the Costa Awards (Roffey won the overall Costa Book of the Year).

The crystal-clear winner for me is In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado, her memoir of an abusive same-sex relationship. Written in the second person and in short sections that examine her memories from different angles, it’s a masterpiece and a real game changer for the genre – which I’m sure is just what the judges are looking for.

The only book on the shortlist that came anywhere close to this one, for me, was A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, an elegant piece of feminist autofiction that weaves in biography, imagination, and poetry. It would be a fine runner-up choice.

(On the Rathbones Folio Prize Twitter account, you will find lots of additional goodies like links to related articles and interviews, and videos with short readings from each author.)

My thanks to the publishers and FMcM Associates for the free copies for review.

The Rathbones Folio Prize 2021 Shortlist

The Rathbones Folio Prize is unique in that nominations come from the Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, and any book written in English is eligible, so nonfiction and poetry share space with fiction on the varied shortlist of eight titles:

- handiwork by Sara Baume (Tramp Press)

- Indelicacy by Amina Cain (Daunt Books)

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney (Harvill Secker)

- Poor by Caleb Femi (Penguin)

- My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long (Picador)

- In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado (Serpent’s Tail)

- A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa (Tramp Press)

- The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey (Peepal Tree Press)

I was delighted to be sent the whole shortlist to feature. I’d already read Rachel Long’s poetry collection and Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir (reviewed here), but I’m keen to start on the rest and will read and review as many as possible before the online prize announcement on Wednesday the 24th. I’m starting with the Baume, Cain, Femi and Roffey.

I was delighted to be sent the whole shortlist to feature. I’d already read Rachel Long’s poetry collection and Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir (reviewed here), but I’m keen to start on the rest and will read and review as many as possible before the online prize announcement on Wednesday the 24th. I’m starting with the Baume, Cain, Femi and Roffey.

For more information on the prize, these eight authors, and the longlist, see the website.

(The remainder of the text in this post comes from the official press release.)

The Rathbones Folio Prize — known as the “writers’ prize” — rewards the best work of literature of the year, regardless of form. It is the only award governed by an international academy of distinguished writers and critics, ensuring a unique quality and consistency in the nomination and judging process.

The judges (Roger Robinson, Sinéad Gleeson, and Jon McGregor) have chosen books by seven women and one man to be in contention for the £30,000 prize which looks for the best fiction, non-fiction and poetry in English from around the world. Six out of the eight titles are by British and Irish writers, with three out of Ireland alone (two of which are published by the same publisher, Tramp Press). The spirit of experimentation is also reflected in the strong showing of independent publishers and small presses (five out of eight).

Chair of judges Roger Robinson says: “It was such a joy to spend detailed and intimate time with the books nominated for the Rathbones Folio Prize and travel deep into their worlds. The judges chose the eight books on the shortlist because they are pushing at the edges of their forms in interesting ways, without sacrificing narrative or execution. The conversations between the judges may have been as edifying as the books themselves. From a judges’ vantage point, the future of book publishing looks incredibly healthy – and reading a book is still one of the most revolutionary things that one can do.”

The 2021 shortlist ranges from Amina Cain’s Indelicacy – a feminist fable about class and desire – and the exploration of the estates of South London through poetry and photography in Caleb Femi’s Poor, to a formally innovative, genre-bending memoir about domestic abuse in Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, and a feminist revision of Caribbean mermaid myths, in Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch.

The 2021 shortlist ranges from Amina Cain’s Indelicacy – a feminist fable about class and desire – and the exploration of the estates of South London through poetry and photography in Caleb Femi’s Poor, to a formally innovative, genre-bending memoir about domestic abuse in Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, and a feminist revision of Caribbean mermaid myths, in Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch.

In the darkly comic novel As You Were, poet Elaine Feeney tackles the intimate histories, institutional failures, and the darkly present past of modern Ireland, while Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat finds the eighteenth-century poet Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill haunting the life of a contemporary young mother, prompting her to turn detective. Doireann Ní Ghríofa is published by Dublin’s Tramp Press, also publishers of Sara Baume’s handiwork – which charts the author’s daily process of making and writing, and explores what it is to create and to live as an artist – while poet Rachel Long’s acclaimed debut collection My Darling from the Lions skewers sexual politics, religious awakenings and family quirks with wit, warmth and precision.

My thanks to the publishers and FMcM Associates for the free copies for review.

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher) Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order) Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted  Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download) Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download) Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer. The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.” Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download) Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.” Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”. John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download) Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download) Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download) The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download) Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.” It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download) Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.” Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy) Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download) Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.” The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download) Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download) Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.” Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood. I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through. Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with  In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today).

In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today). My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions.

My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions. I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction. In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible).

In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible). In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most.

In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most. Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

I’d expected this to be just a picture book. Instead, it’s a guided tour through four landscapes – the garden, the woods, the uplands, and a river – and it combines Robert Macfarlane-esque poetry (the rhyming and alliteration are reminiscent of The Lost Words books) with facts and crafts/activities. It starts small, with the birds a child in the UK might be able to see out their window, and then ventures further afield. There is a teaching focus, with information on species’ classification, life cycles and migrations. I also learned to recognize hazel catkins and flowers, and then identified them on our walk later the same day! But the main aim, I think, is simply to encourage wonder and inspire children to get outside and explore the nature around them. I liked the illustrations, but wish the birds hadn’t been given slightly googly eyes. (Public library)

I’d expected this to be just a picture book. Instead, it’s a guided tour through four landscapes – the garden, the woods, the uplands, and a river – and it combines Robert Macfarlane-esque poetry (the rhyming and alliteration are reminiscent of The Lost Words books) with facts and crafts/activities. It starts small, with the birds a child in the UK might be able to see out their window, and then ventures further afield. There is a teaching focus, with information on species’ classification, life cycles and migrations. I also learned to recognize hazel catkins and flowers, and then identified them on our walk later the same day! But the main aim, I think, is simply to encourage wonder and inspire children to get outside and explore the nature around them. I liked the illustrations, but wish the birds hadn’t been given slightly googly eyes. (Public library)

Like many, I discovered Ní Ghríofa through

Like many, I discovered Ní Ghríofa through