August Releases: Sarah Manguso (Fiction), Sarah Moss (Memoir), and Carl Phillips (Poetry)

Today I feature a new-to-me poet and two women writers whose careers I’ve followed devotedly but whose latest books – forthright yet slippery; their genre categories could easily be reversed – I found very emotionally difficult to read. Gruelling, almost, but admirable. Many rambling thoughts ensue. Then enjoy a nice poem.

Liars by Sarah Manguso

As part of a profile of Manguso and her oeuvre for Bookmarks magazine, I wrote a synopsis and surveyed critical opinion; what follow are additional subjective musings. I’ve read six of her nine books (all but the poetry and an obscure flash fiction collection) and I esteem her fragmentary, aphoristic prose, but on balance I’m fonder of her nonfiction. Had Liars been marketed as a diary of her marriage and divorce, Manguso might have been eviscerated for the indulgence and one-sided presentation. With the thinnest of autofiction layers, is it art?

Jane recounts her doomed marriage, from the early days of her relationship with John Bridges to the aftermath of his affair and their split. She is a writer and academic who sacrifices her career for his financially risky artistic pursuits. Especially once she has a baby, every domestic duty falls to her, while he keeps living like a selfish stag and gaslights her if she tries to complain, bringing up her history of mental illness. The concise vignettes condense 14+ years into 250 pages, which is a relief because beneath the sluggish progression is such repetition of type of experiences that it could feel endless. John’s last name might as well be Doe: The novel presents him – and thus all men – as despicable and useless, while women are effortlessly capable and, by exhausting themselves, achieve superhuman feats. This is what heterosexual marriage does to anyone, Manguso is arguing. Indeed, in a Guardian interview she characterized this as a “domestic abuse novel,” and elsewhere she has said that motherhood can be unlinked from patriarchy, but not marriage.

Let’s say I were to list my every grievance against my husband from the last 17+ years: every time he left dirty clothes on the bedroom floor (which is every day); every time he loaded the dishwasher inefficiently (which is every time, so he leaves it to me); every time he failed to seal a packet or jar or Tupperware properly (which – yeah, you get the picture) – and he’s one of the good guys, bumbling rather than egotistical! And he’d have his own list for me, too. This is just what we put up with to live with other people, right? John is definitely worse (“The difference between John and a fascist despot is one of degree, not type”). But it’s not edifying, for author or reader. There may be catharsis to airing every single complaint, but how does it help to stew in bitterness? Look at everything I went through and validate my anger.

There are bright spots: Jane’s unexpected transformation into a doting mother (but why must their son only ever be called “the child”?), her dedication to her cat, and the occasional dark humour:

So at his worst, my husband was an arrogant, insecure, workaholic, narcissistic bully with middlebrow taste, who maintained power over me by making major decisions without my input or consent. It could still be worse, I thought.

Manguso’s aphoristic style makes for many quotably mordant sentences. My feelings vacillated wildly, from repulsion to gung-ho support; my rating likewise swung between extremes and settled in the middle. I felt that, as a feminist, I should wholeheartedly support a project of exposing wrongs. It’s easy to understand how helplessness leads to rage, and how, considering sunk costs, a partner would irrationally hope for a situation to improve. So I wasn’t as frustrated with Jane as some readers have been. But I didn’t like the crass sexual language, and on the whole I agreed with Parul Sehgal’s brilliant New Yorker review that the novel is so partial and the tone so astringent that it is impossible to love. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

And a quote from the Moss memoir (below) to link the two books: “Homes are places where vulnerable people are subject to bullying, violence and humiliation behind closed doors. Homes are places where a woman’s work is never done and she is always guilty.”

20 Books of Summer, #19:

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I’ve reviewed this memoir for Shelf Awareness (it’s coming out in the USA from Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 22nd) so will only give impressions, in rough chronological order:

Sarah Moss returns to nonfiction – YES!!!

Oh no, it’s in the second person. I’ve read too much of that recently. Fine for one story in a collection. A whole book? Not so sure. (Kirsty Logan got away with it, but only because The Unfamiliar is so short and meant to emphasize how matrescence makes you other.)

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

Once she starts discussing her childhood reading – what it did for her then and how she views it now – the book really came to life for me. And she very effectively contrasts the would-be happily ever after of generally getting better after eight years of disordered eating with her anorexia returning with a vengeance at age 46 – landing her in A&E in Dublin. (Oh! when she reads War and Peace over and over on a hospital bed and defiantly uses the clean toilets on another floor.) This crisis is narrated in the third person before a return to second person.

The tone shifts throughout the book, so that what threatens to be slightly cloying in the childhood section turns academically curious and then, somehow, despite the distancing pronouns, intimate. So much so that I found myself weeping through the last chapters over this lovely, intelligent woman’s ongoing struggles. As an overly cerebral person who often thinks it’s pesky to have to live in a body, I appreciated her probing of the body/mind divide; and as she tracks where her food issues came from, I couldn’t help but think about my sister’s years of eating disorders and my mother’s fear that it was all her fault.

Beyond Moss’s usual readers, I’d also recommend this to fans of Laura Freeman’s The Reading Cure and Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place.

Overall: shape-shifting, devastating, staunchly pragmatic. I’m not convinced it all hangs together (and I probably would have ended it at p. 255), but it’s still a unique model for transmuting life into art. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Will I remember individual poems? Unlikely. But the sense of chilly, clear-eyed reflection, yes. (Sample poem below) ![]()

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

Record of Where a Wind Was

Wave-side, snow-side,

little stutter-skein of plovers

lifting, like a mind

of winter—

We’d been walking

the beach, its unevenness

made our bodies touch,

now and then, at

the shoulders mostly,

with that familiarity

that, because it sometimes

includes love, can

become confused with it,

though they remain

different animals. In my

head I played a game with

the waves called Weapon

of Choice, they kept choosing

forgiveness, like the only

answer, as to them

it was, maybe. It’s a violent

world. These, I said, I choose

these, putting my bare hands

through the air in front of me.

Any other August releases you’d recommend?

Reading Ireland Month: Seán Hewitt, Maggie O’Farrell

Reading Ireland Month is hosted each year by Cathy of 746 Books. I’m wishing you all well on St. Patrick’s Day with this first of two planned tie-in posts. Today I have a poetry collection that sets grief and queer longing amid nature, and my last unread novel – a somewhat middling one, unfortunately – by one of my favourite authors.

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt (2024)

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

In “Two Apparitions,” the poet’s late father seems visible again. Many of the scenes take place at dusk or dark. There’s a layer of menace to “Night-Scented Stock,” about an abusive relationship, and the account of a slaughter in “Pig.” But the stand-out is “We Didn’t Mean to Kill Mr Flynn,” based on the 1982 murder of a gay man in a Dublin park. Hewitt drew lines from court proceedings and periodicals in the Irish Queer Archive at the National Library of Ireland, where he was poet in residence. He voices first the gang of killers, then Flynn himself. The trial kickstarted Ireland’s Pride movement.

More favourite lines:

Come out, make a verb of me, let

my body do your speaking tonight —

(from “A Strain of the Earth’s Sweet Being”)

awestruck, bright,

a child in the bell-tower of beauty —

(from “Skylarks”)

Love, the world is failing:

come and fail with me.

(from “Nightfall”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

My Lover’s Lover by Maggie O’Farrell (2002)

I was so excited, a few years ago, to find battered copies of this and After You’d Gone in a local charity shop for 50 pence each, even though it appears a mouse had a nibble on one corner here. They were her first two books, but the last that I managed to source. Whereas After You’d Gone is a surprisingly confident and elegant debut novel about a woman in a coma and the family and romantic relationships that brought her to this point, My Lover’s Lover ultimately felt like a pretty run-of-the-mill story about two women finding out that (some) men are dogs and they need to break free.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

As in some later novels, there are multiple locales (here, NYC, the Australian desert, and China – a country O’Farrell often revisits in fiction) and complicated point-of-view shifts, but I felt the sophisticated craft was rather wasted on a book that boils down to a self-explanatory maxim: past relationships always have an effect on current ones. I also found the writing overmuch in places (“the grass swooshing, sussurating, cleaving open to her steps”; “letting fall a box of cereal into its [a shopping trolley’s] chrome meshing”; “her fingertips meeting the ceraceous, heated skin of his cheek”). However, this was an engrossing read – I read most of it in two days. It’s bottom-tier O’Farrell, though, along with The Distance Between Us and Hamnet – sorry, I know many adore it. (If you’re interested: middle tier = The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, Instructions for a Heatwave, her two children’s books, and The Marriage Portrait; top tier = After You’d Gone, The Hand that First Held Mine, This Must Be the Place, and I Am, I Am, I Am.)

I’ve gotten in the habit of reading one of Maggie O’Farrell’s works per year, so I will just have to reread my favourites until we get a new one. I’m already tapping a foot in impatience. (Secondhand from Bas, Newbury)

Have you read any Irish literature this month?

A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley (Blog Tour)

Silver Moon, one of the Charing Cross Road bookshops, was a London institution from 1984 until its closure in 2001. “Feminism and business are strange bedfellows,” Jane Cholmeley soon realised, and this book is her record of the challenges of combining the two. On the spectrum of personal to political, this is much more manifesto than memoir. She dispenses with her own story (vicar’s tomboy daughter, boarding school, observing racism on a year abroad in Virginia, secretarial and publishing jobs, meeting her partner) via a 10-page “Who Am I?” opening chapter. However, snippets of autobiography do enter into the book later on; in one of my favourite short chapters, “Coming Out,” Cholmeley recalls finally telling her mother that she was a lesbian after she and Sue had been together nearly a decade.

The mid-1980s context plays a major role: Thatcherite policies (Section 28 outlawing the “promotion of homosexuality”), negotiations with the Greater London Council, and trying to share the landscape with other feminist bookshops like Sisterwrite and Virago. Although there were some low-key rivalries and mean-spirited vandalism, a spirit of camaraderie generally prevailed. Cholmeley estimates that about 30% of the shop’s customers were men, but the focus here was always on women. The events programme featured talks by an amazing who’s-who of women authors, Cholmeley was part of the initial roundtable discussions in 1992 that launched the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize), and the café was designated a members’ club so that it could legally be a women-only space.

I’ve always loved reading about what goes on behind the scenes in bookshops (The Diary of a Bookseller, Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop, The Sentence, The Education of Harriet Hatfield, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, and so on), and Cholmeley ably conveys the buzzing girl-power atmosphere of hers. There is a fun sense of humour, too: “Dyke and Doughnut” was a potential shop name, and a letter to one potential business partner read, “you already eat lentils, and ride a bicycle, so your standard of living hasn’t got much further to fall, we happen to like you an awful lot, and think we could all work together in relative harmony”.

However, the book does not have a narrative per se; the “A Day in the Life of… (1996)” chapter comes closest to what those hoping for a bookseller memoir might be expecting, in that it actually recreates scenes and dialogue. The rest is a thematic chronicle, complete with lists, sales figures, profitability charts, and excerpted documents, and I often got lost in the detail. The fact that this gives the comprehensive history of one establishment makes it a nostalgic yearbook that will appeal most to readers who have a head for business, were dedicated Silver Moon customers, and/or hold a particular personal or academic interest in the politics of the time and the development of the feminist and LGBT movements.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Mudlark for the free copy for review.

Buy A Bookshop of One’s Own from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was happy to be part of the blog tour for the release of this book. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

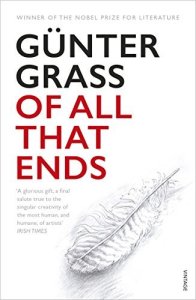

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

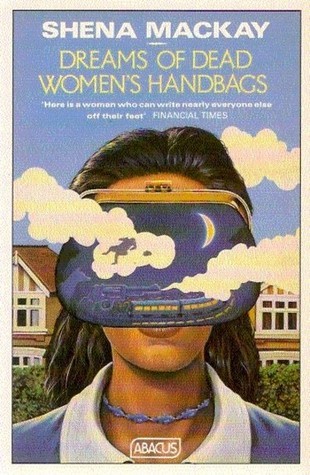

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page. I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls  Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey. What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read  I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]  “They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]  I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]  {BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]  Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.