Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

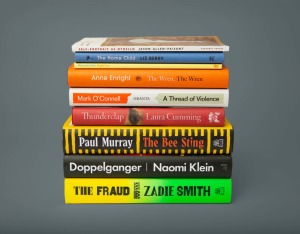

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

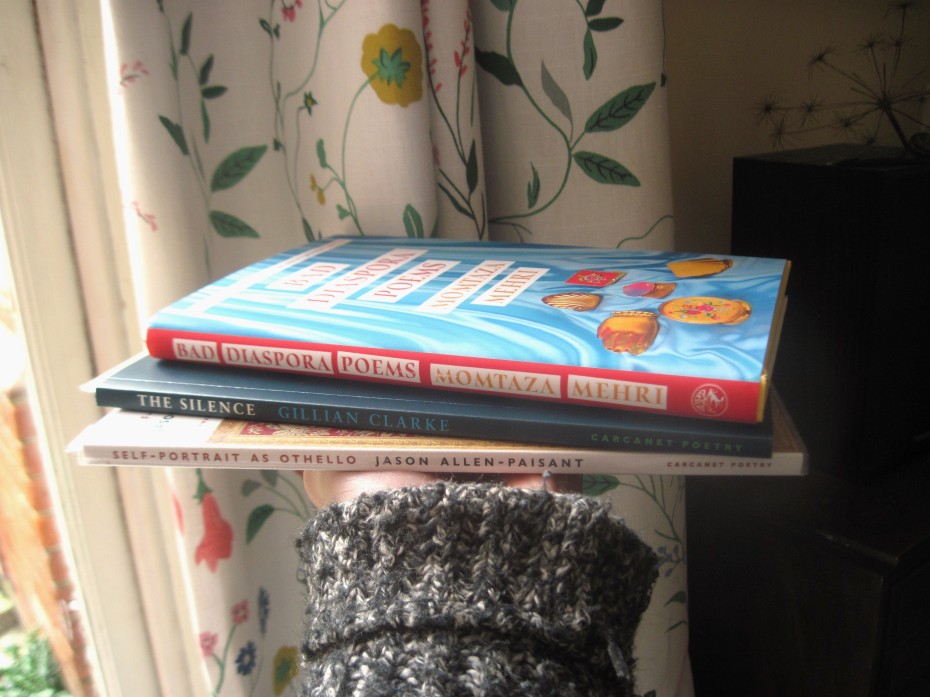

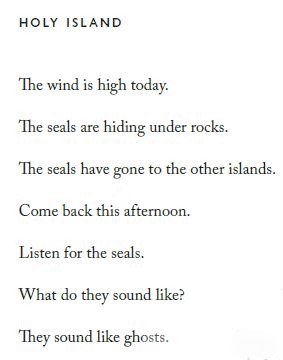

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

#NovNov22 Nonfiction Week Begins! with Strangers on a Pier by Tash Aw

Short nonfiction week of Novellas in November is (not so) secretly my favourite theme of this annual challenge. About 40% of my reading is nonfiction, and I love finding books that illuminate a topic or a slice of life in well under 200 pages. I’ll see if I can review one per day this week.

Back in 2013 I read Tash Aw’s Booker-longlisted Five Star Billionaire and thought it was a fantastic novel about strangers thrown together in contemporary Shanghai. I don’t know why it hadn’t occurred to me to find something else by him in the meantime, but when I spotted this slim volume up in the library’s biography section, I knew it had to come home with me.

Originally published in the USA as The Face in 2016, this is a brief family memoir reflecting on migration and belonging. Aw was born in Taiwan and grew up in Malaysia in an ethnically Chinese family; wherever he goes, he can pass as any number of Asian ethnicities. Both of his grandfathers were Chinese immigrants to Malaysia, but from different regions and speaking separate dialects. (This is something those of us in the West unfamiliar with China can struggle to understand: it has no monolithic identity or language. The food and culture might vary as much by region as they do in, say, different countries of Europe.)

Originally published in the USA as The Face in 2016, this is a brief family memoir reflecting on migration and belonging. Aw was born in Taiwan and grew up in Malaysia in an ethnically Chinese family; wherever he goes, he can pass as any number of Asian ethnicities. Both of his grandfathers were Chinese immigrants to Malaysia, but from different regions and speaking separate dialects. (This is something those of us in the West unfamiliar with China can struggle to understand: it has no monolithic identity or language. The food and culture might vary as much by region as they do in, say, different countries of Europe.)

Aw imagines his ancestors’ arrival and the disorientation they must have known as they made their way to an address on a piece of paper. His family members never spoke about their experiences, but the sense of being an outsider, a minority is something that has recurred through their history. Aw himself felt it keenly as a university student in Britain.

After the first long essay, “The Face,” comes a second, “Swee Ee, or Eternity,” addressed in the second person to his late grandmother, about whom, despite having worked in her shop as a boy, he knew next to nothing before he spent time with her as she was dying of cancer.

When is short nonfiction too short? Well, I feel that what I just read was actually two extended magazine articles rather than a complete book – that I read a couple of stories rather than the whole story. Perhaps that is inevitable for such a short autobiographical work, though I can think of two previous memoirs from last year alone that managed to be comprehensive, self-contained and concise: The Story of My Life by Helen Keller and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy. (Public library)

[91 pages]

Two Recommended January Releases: Dominicana and Let Me Be Frank

Much as I’d like to review books in advance of their release dates, that doesn’t seem to be how things are going this year. I hope readers will find it useful to learn about recent releases they might have missed.

This month I’m featuring a fictionalized immigration story from the Dominican Republic and a collection of autobiographical comics by a New Zealander.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz

(Published by John Murray on the 23rd)

It’s easy to assume that all the immigration (or Holocaust, or WWI; whatever) stories have been told. This is proof that that is not true; it felt completely fresh to me. Ana Canción is 11 when Juan Ruiz first proposes to her in 1961 – the same year dictator Rafael Trujillo is assassinated, throwing their native Dominican Republic into chaos. The Ruiz brothers are admired for their entrepreneurial spirit; they jet back and forth to New York City to earn money they plan to invest in a restaurant back home. To Ana’s parents, pairing their daughter with a man with such good prospects makes financial sense, so though Ana doesn’t love him and knows nothing about sex, she finds herself married to Juan at age 15. With fake papers that claim she’s 19, she arrives in New York on the first day of 1965 to start a new life.

It is not the idyll she expected. Ana often feels confused and isolated in their tiny apartment, and the political unrest in NYC (e.g. the assassination of Malcolm X) and in DR mirrors the turbulence of her marriage. Juan is violent and unfaithful, and although Ana dreams of leaving him she soon learns that she is pregnant and has to think of her duty to her family, who expect to join her in America. The content of the novel could have felt like heavy going, but Ana is such a plucky and confiding narrator that you’re drawn into her world and cheer for her as she comes up with ways to earn money of her own (such as selling pastelitos to homesick factory workers and at the World’s Fair) and figures out what she wants from life.

It is not the idyll she expected. Ana often feels confused and isolated in their tiny apartment, and the political unrest in NYC (e.g. the assassination of Malcolm X) and in DR mirrors the turbulence of her marriage. Juan is violent and unfaithful, and although Ana dreams of leaving him she soon learns that she is pregnant and has to think of her duty to her family, who expect to join her in America. The content of the novel could have felt like heavy going, but Ana is such a plucky and confiding narrator that you’re drawn into her world and cheer for her as she comes up with ways to earn money of her own (such as selling pastelitos to homesick factory workers and at the World’s Fair) and figures out what she wants from life.

This allowed me to imagine what it would be like to have an arranged marriage and arrive in a country not knowing a word of the language. Cruz based the story on her mother’s experience, even though her mother thought her life was too common and boring to interest anyone. The literary style – short chapters with no speech marks – could be offputting for some but worked for me, and I loved the tongue-in-cheek references to I Love Lucy. Had I only managed to read this in December, it would have been on my Best of 2019 list – it was first published in September by Flatiron Books, USA.

Let Me Be Frank by Sarah Laing

(Published by Lightning Books on the 16th)

Laing is a novelist and comics artist from New Zealand known for her previous graphic memoir, Mansfield and Me, about her obsession with acclaimed NZ writer Katherine Mansfield. This collection brings together the autobiographical comics that originally appeared on Laing’s blog of the same title in 2010‒19. She started posting the comics when she was writer-in-residence at the Frank Sargeson Centre in Auckland. (I know the name Sargeson because he helped Janet Frame when she was early in her career.)

Laing is a novelist and comics artist from New Zealand known for her previous graphic memoir, Mansfield and Me, about her obsession with acclaimed NZ writer Katherine Mansfield. This collection brings together the autobiographical comics that originally appeared on Laing’s blog of the same title in 2010‒19. She started posting the comics when she was writer-in-residence at the Frank Sargeson Centre in Auckland. (I know the name Sargeson because he helped Janet Frame when she was early in her career.)

So what is the book about? All of life, really: growing up with type 1 diabetes, having boyfriends, being part of a family, the constant niggle of body issues, struggling as a writer, and trying to be a good mother. Other specific topics include her teenage obsession with music (especially Morrissey) and her run-ins with various animals (a surprising number of dead possums!). She ruminates about the times when she hasn’t done enough to help people who were in trouble. She also admits her confusion about fashion: she is always looking for, but never finding, ‘her look’. And is she modeling a proper female identity for her children? “I feel like I’m betraying feminism, buying my daughter a fairy princess dress,” she frets.

But even as she expresses these worries, she wonders how genuine she can be since they form the basis of her art. Is she just “publically performing my neuroses”? The work/life divide is especially tricksy when your life inspires your work.

I took half a month to read these comics on screen, usually just a few pages a day. It’s a tough book to assess as a whole because there is such a difference between the full-color segments and the sketch-like black-and-white ones. There is also a ‘warts-and-all’ approach here, with typos and cross-outs kept in. (Two that made me laugh were “aesophegus” [for oesophagus] and “Diana Anthill”!) Overall, though, I think this is a relatable and fun book that would suit fans of Alison Bechdel and Roz Chast but should also draw in readers new to the graphic novel format.

My thanks to Eye/Lightning Books for sending me an e-book to review.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Dylan Thomas Prize Blog Tour: Eye Level by Jenny Xie

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so short stories and poetry sit alongside novels on this year’s longlist of 12 titles:

- Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Friday Black

- Michael Donkor, Hold

- Clare Fisher, How the Light Gets In

- Zoe Gilbert, Folk

- Emma Glass, Peach

- Guy Gunaratne, In Our Mad and Furious City

- Louisa Hall, Trinity

- Sarah Perry, Melmoth

- Sally Rooney, Normal People

- Richard Scott, Soho

- Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, House of Stone

- Jenny Xie, Eye Level

For this stop on the official blog tour, I’m featuring the debut poetry collection Eye Level by Jenny Xie (winner of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets), which was published by Graywolf Press in 2018 and was a National Book Award finalist in the USA last year. Xie, who was born in Hefei, China and grew up in New Jersey, now teaches at New York University. Her poems focus on the sense of displacement that goes hand in hand with immigration or just everyday travel, and on familial and evolutionary inheritance.

The opening sequence of poems is set in Vietnam, Cambodia and Corfu, with heat and rain as common experiences that also enter into the imagery: “See, counting’s hard in half-sleep, and the rain pulls a sheet // over the sugar palms and their untroubled leaves” and “The riled heat reaches the river shoal before it reaches the dark.” The tragic and the trivial get mixed up in ordinary sightseeing:

The tourists curate vacation stories,

days summed up in a few lines.

Killing fields tour, Sambo the elephant

in clotted street traffic,

dusky-complexioned children hesitant in their approach.

Seeing and being seen are a primary concern, with the “eye” of the title deliberately echoing the “I” that narrates most of the poems. I actually wondered if there was a bit too much first person in the book, which always complicates the question of whether the narrator equals the poet. One tends to assume that the story of a father going to study in the USA and the wife following, giving up her work as a doctor for a dining hall job, is autobiographical. The same goes for the experiences in “Naturalization” and “Exile.”

The metaphors Xie uses for places are particularly striking, often likening a city/country to a garment or a person’s appearance: “Seeing the collars of this city open / I wish for higher meaning and its histrionics to cease,” “The new country is ill fitting, lined / with cheap polyester, soiled at the sleeves,” and “Here’s to this new country: / bald and without center.”

The poet contemplates what she has absorbed from her family line and upbringing, and remembers the sting of feeling left behind when a romance ends:

I thought I owned my worries, but here I was only pulled along by the needle

of genetics, by my mother’s tendency to pry at openings in her life.

Love’s laws are simple. The leaving take the lead.

The left-for takes a knife to the knots of narrative.

Those last two lines are a good example of the collection’s reliance on alliteration, which, along with repetition, is used much more often than end rhymes and internal or slant rhymes. Speaking of which, this was my favorite pair of lines:

Slant rhyme of current thinking

and past thinking.

Meanwhile, my single favorite poem was “Hardwired,” about the tendency to dwell on the negative:

Though I didn’t always connect with Xie’s style – it can be slightly detached and formal in a way that is almost at odds with the fairly personal subject matter, and there were some pronouncements that seemed to me not as profound as they intended to be (it may well be that her work would be best read aloud) – there were occasional lines and images that pulled me up short and made me think, Yes, she gets it. What it’s like to be from one place but live in another; what it’s like to be fond but also fearful of the ways in which you resemble your parents. I expect this to be a strong contender for the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist, which will be announced on April 2nd. The winner is then announced on May 16th.

My thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

This was our January book club read. We’d had good luck with Gale before: his Notes from an Exhibition received our joint highest rating ever. As he’s often done in his fiction, he took inspiration from family history: here, the story of his great-grandfather Harry Cane, who emigrated to the Canadian prairies to farm in the most challenging of conditions. Because there is some uncertainty as to what precipitated his ancestor’s resettlement, Gale has chosen to imagine that Harry, though married and the father of a daughter, was in fact gay and left England to escape blackmailing and disgrace after his affair with a man was discovered.

This was our January book club read. We’d had good luck with Gale before: his Notes from an Exhibition received our joint highest rating ever. As he’s often done in his fiction, he took inspiration from family history: here, the story of his great-grandfather Harry Cane, who emigrated to the Canadian prairies to farm in the most challenging of conditions. Because there is some uncertainty as to what precipitated his ancestor’s resettlement, Gale has chosen to imagine that Harry, though married and the father of a daughter, was in fact gay and left England to escape blackmailing and disgrace after his affair with a man was discovered.

A brief second review for Nordic FINDS. It’s the third time I’ve encountered some of these autofiction stories: this was a reread for me, and 13 of the pieces are also in Sculptor’s Daughter, which I skimmed from the library a few years ago. And yet I remembered nothing; not a single one was memorable. Most of the pieces are impressionistic first-person fragments of childhood, with family photographs interspersed. In later sections, the protagonist is an older woman, Jansson herself or a stand-in. I most enjoyed “Messages” and “Correspondence,” round-ups of bizarre comments and requests she received from readers. Of the proper stories, “The Iceberg” was the best. It’s a literal object the speaker alternately covets and fears, and no doubt a metaphor for much else. This one had the kind of profound lines Jansson slips into her children’s fiction: “Now I had to make up my mind. And that’s an awful thing to have to do” and “if one doesn’t dare to do something immediately, then one never does it.” A shame this wasn’t a patch on

A brief second review for Nordic FINDS. It’s the third time I’ve encountered some of these autofiction stories: this was a reread for me, and 13 of the pieces are also in Sculptor’s Daughter, which I skimmed from the library a few years ago. And yet I remembered nothing; not a single one was memorable. Most of the pieces are impressionistic first-person fragments of childhood, with family photographs interspersed. In later sections, the protagonist is an older woman, Jansson herself or a stand-in. I most enjoyed “Messages” and “Correspondence,” round-ups of bizarre comments and requests she received from readers. Of the proper stories, “The Iceberg” was the best. It’s a literal object the speaker alternately covets and fears, and no doubt a metaphor for much else. This one had the kind of profound lines Jansson slips into her children’s fiction: “Now I had to make up my mind. And that’s an awful thing to have to do” and “if one doesn’t dare to do something immediately, then one never does it.” A shame this wasn’t a patch on

Laila (Big Reading Life) and I attempted this as a buddy read, but we both gave up on it. I got as far as page 53 (in the 600+-page pocket paperback). The premise was alluring, with a magical white horse swooping in to rescue Peter Lake from a violent gang. I also appreciated the NYC immigration backstory, but not the adjective-heavy wordiness, the anachronistic exclamations (“Crap!” and “Outta my way, you crazy midget” – this is presumably set some time between the 1900s and 1920s) or the meandering plot. It was also disturbing to hear about Peter’s sex life when he was 12. From a Little Free Library (at Philadelphia airport) it came, and to a LFL (at the Bar Convent in York) it returned. Laila read a little further than me, enough to tell the library patron who recommended it to her that she’d given it a fair try.

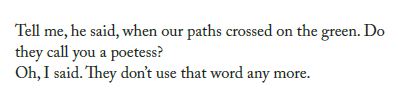

Laila (Big Reading Life) and I attempted this as a buddy read, but we both gave up on it. I got as far as page 53 (in the 600+-page pocket paperback). The premise was alluring, with a magical white horse swooping in to rescue Peter Lake from a violent gang. I also appreciated the NYC immigration backstory, but not the adjective-heavy wordiness, the anachronistic exclamations (“Crap!” and “Outta my way, you crazy midget” – this is presumably set some time between the 1900s and 1920s) or the meandering plot. It was also disturbing to hear about Peter’s sex life when he was 12. From a Little Free Library (at Philadelphia airport) it came, and to a LFL (at the Bar Convent in York) it returned. Laila read a little further than me, enough to tell the library patron who recommended it to her that she’d given it a fair try. This is the third collection by the Irish poet; I’d previously read her The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx. Grouped into nine thematic sections, these very short poems take the form of few-sentence aphorisms or riddles, with the titles, printed in the bottom corner, often acting as something of a punchline – especially because I had them on my e-reader and they only appeared after I’d turned the digital ‘page’. Some appear to be autobiographical, about life for a female academic. Others are political (I loved “Tenants and Landlords”), or about wolves or blackbirds. The verse in “Constructions” takes different shapes on the page. Here are “The Subject Field” and “The Actor”:

This is the third collection by the Irish poet; I’d previously read her The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx. Grouped into nine thematic sections, these very short poems take the form of few-sentence aphorisms or riddles, with the titles, printed in the bottom corner, often acting as something of a punchline – especially because I had them on my e-reader and they only appeared after I’d turned the digital ‘page’. Some appear to be autobiographical, about life for a female academic. Others are political (I loved “Tenants and Landlords”), or about wolves or blackbirds. The verse in “Constructions” takes different shapes on the page. Here are “The Subject Field” and “The Actor”:

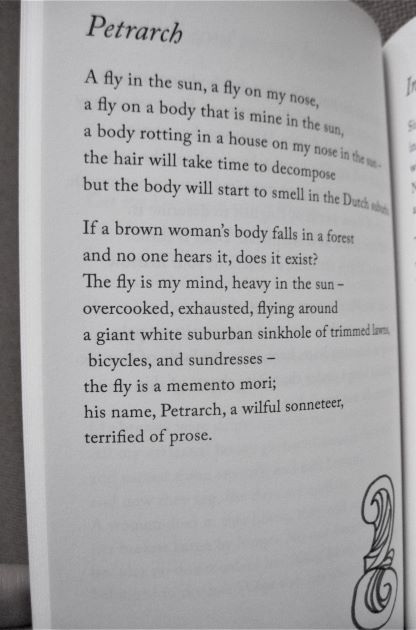

I love the Matisse cut-outs on the cover of Draycott’s fifth collection. The title poem’s archaic spelling (“hyther,” “releyf”) contrast with its picture of a modern woman seeking respite from “the men coming on to you / the taxi drivers saying here jump in no / no you don’t need no money.” Country vs. city, public vs. private, pastoral past and technological future are some of the dichotomies the verse plays with. I enjoyed the alliteration and references to an old English herbarium, Derek Jarman and polar regions. However, it was hard to find overall linking themes to latch onto.

I love the Matisse cut-outs on the cover of Draycott’s fifth collection. The title poem’s archaic spelling (“hyther,” “releyf”) contrast with its picture of a modern woman seeking respite from “the men coming on to you / the taxi drivers saying here jump in no / no you don’t need no money.” Country vs. city, public vs. private, pastoral past and technological future are some of the dichotomies the verse plays with. I enjoyed the alliteration and references to an old English herbarium, Derek Jarman and polar regions. However, it was hard to find overall linking themes to latch onto.

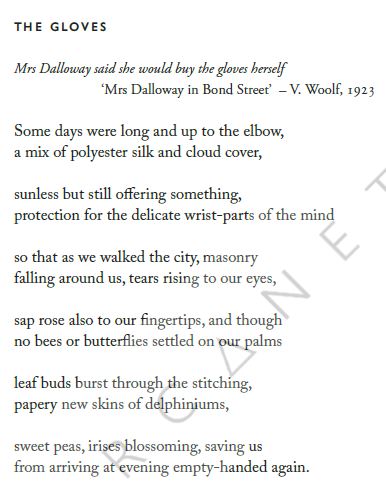

Brimming with striking metaphors and theological echoes, the first poetry collection by the Houston-based writer is an elegant record of family life on both sides of the Mexican border. “Laredo Duplex” (below) explains how violence prompted the family’s migration. “The Contract” recalls acting as a go-between for a father who didn’t speak English; in “Diáspora” the speaker is dubious about assimilation: “I am losing my brother to whiteness.” The tone is elevated and philosophical (“You take the knife of epistemology and the elegiac fork”), with ample alliteration. Flora and fauna and the Bible are common sources of unexpected metaphors. Lopez tackles big issues of identity, loss and memory in delicate verse suited to readers of Kaveh Akbar. (My full review is on

Brimming with striking metaphors and theological echoes, the first poetry collection by the Houston-based writer is an elegant record of family life on both sides of the Mexican border. “Laredo Duplex” (below) explains how violence prompted the family’s migration. “The Contract” recalls acting as a go-between for a father who didn’t speak English; in “Diáspora” the speaker is dubious about assimilation: “I am losing my brother to whiteness.” The tone is elevated and philosophical (“You take the knife of epistemology and the elegiac fork”), with ample alliteration. Flora and fauna and the Bible are common sources of unexpected metaphors. Lopez tackles big issues of identity, loss and memory in delicate verse suited to readers of Kaveh Akbar. (My full review is on

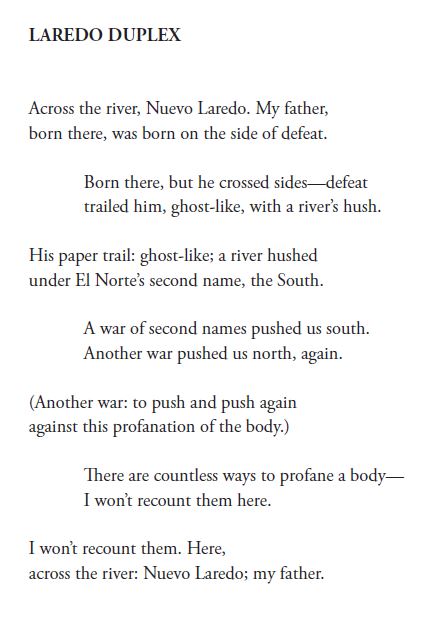

This debut collection has Rizwan juxtaposing East and West, calling out European countries for the prejudice she has experienced as a Muslim Pakistani in academia. She has also lived in the UK and USA, but mostly reflects on time spent in Germany and the Netherlands, where her imperfect grasp of the language was an additional way of standing out. “Adjunct” is the source of the cover image: she knocks and knocks for admittance, but finds herself shut out still. Rizwan takes extended metaphors from marriage, motherhood and women’s health: in “My house is becoming like my country,” she imagines her husband instituting draconian laws; in “I have found in my breast,” a visit to a doctor about a lump only exposes her own exoticism (“Basically, the Muslims are metastasizing”). In “Paris Proper,” she experiences the city differently from a friend because of the colonial history of the art. (See also

This debut collection has Rizwan juxtaposing East and West, calling out European countries for the prejudice she has experienced as a Muslim Pakistani in academia. She has also lived in the UK and USA, but mostly reflects on time spent in Germany and the Netherlands, where her imperfect grasp of the language was an additional way of standing out. “Adjunct” is the source of the cover image: she knocks and knocks for admittance, but finds herself shut out still. Rizwan takes extended metaphors from marriage, motherhood and women’s health: in “My house is becoming like my country,” she imagines her husband instituting draconian laws; in “I have found in my breast,” a visit to a doctor about a lump only exposes her own exoticism (“Basically, the Muslims are metastasizing”). In “Paris Proper,” she experiences the city differently from a friend because of the colonial history of the art. (See also

Skoulding’s collection is said to be all about Anglesey in Wales, but from that jumping-off point the poems disperse to consider maps, maritime vocabulary, seabirds, islands, tides and much more. There are also translations from the French, various commissions and collaborations, and pieces about the natural vs. the manmade. Some are in paragraph form and there’s a real variety to how lines and stanzas are laid out on the page. I especially liked “Red Squirrels in Coed Cyrnol.” I’ll read more by Skoulding.

Skoulding’s collection is said to be all about Anglesey in Wales, but from that jumping-off point the poems disperse to consider maps, maritime vocabulary, seabirds, islands, tides and much more. There are also translations from the French, various commissions and collaborations, and pieces about the natural vs. the manmade. Some are in paragraph form and there’s a real variety to how lines and stanzas are laid out on the page. I especially liked “Red Squirrels in Coed Cyrnol.” I’ll read more by Skoulding. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review. Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

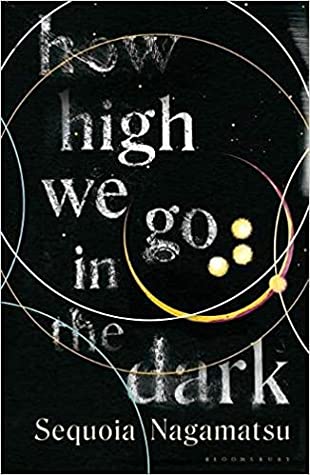

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble.

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble. This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like

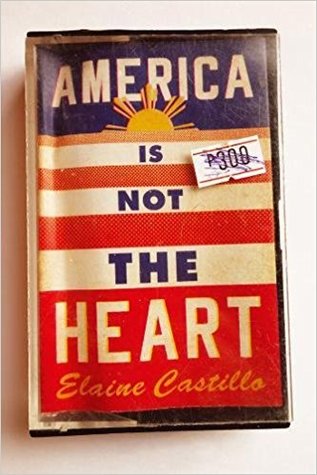

This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like  I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.

I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.

Geronima is a family name for the De Veras; not many realize that Hero, in her mid-thirties and newly arrived in the USA as an undocumented immigrant, and her cousin Roni, her uncle Pol’s seven-year-old daughter, share the same first name. Hero is estranged from her wealthy parents: they were friendly with the Marcos clan, while she ran away to serve as a doctor in the New People’s Army for 10 years. We gradually learn that she was held in a prison camp for two years and subjected to painful interrogations. Still psychologically as well as physically marked by the torture, she is reluctant to trust anyone. She stays under the radar, just taking Roni to and from school and looking after her while her parents are at work.

Geronima is a family name for the De Veras; not many realize that Hero, in her mid-thirties and newly arrived in the USA as an undocumented immigrant, and her cousin Roni, her uncle Pol’s seven-year-old daughter, share the same first name. Hero is estranged from her wealthy parents: they were friendly with the Marcos clan, while she ran away to serve as a doctor in the New People’s Army for 10 years. We gradually learn that she was held in a prison camp for two years and subjected to painful interrogations. Still psychologically as well as physically marked by the torture, she is reluctant to trust anyone. She stays under the radar, just taking Roni to and from school and looking after her while her parents are at work.

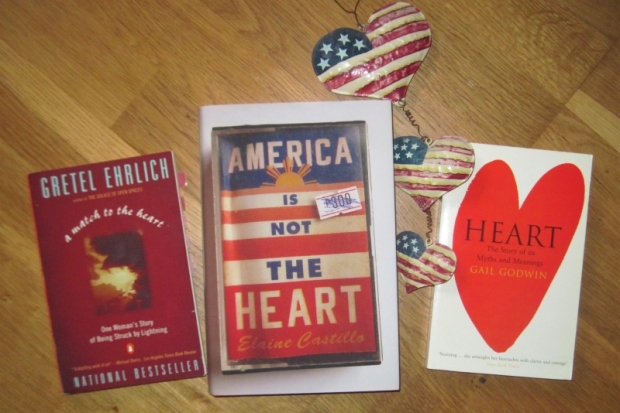

In August 1991, as a summer thunderstorm approached her Wyoming ranch, Ehrlich was struck by lightning. Although she woke up in a pool of blood, her dogs stayed by her side and she was able to haul herself the quarter-mile home and call 911 before she collapsed completely. Being hit by so much electricity (10–30 million volts) had lasting effects on her health. Her heart rhythms were off and she struggled with fatigue for years to come. In a sense, she had died and come back to a subtly different life.

In August 1991, as a summer thunderstorm approached her Wyoming ranch, Ehrlich was struck by lightning. Although she woke up in a pool of blood, her dogs stayed by her side and she was able to haul herself the quarter-mile home and call 911 before she collapsed completely. Being hit by so much electricity (10–30 million volts) had lasting effects on her health. Her heart rhythms were off and she struggled with fatigue for years to come. In a sense, she had died and come back to a subtly different life. I’d read one novel and one memoir by Godwin and was excited to learn that she had once written a wide-ranging study of the religious and literary meanings overlaid on the heart. While there are some interesting pinpricks here, the delivery is shaky: she starts off with a dull, quotation-stuffed, chronological timeline, all too thorough in its plod from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Industrial Revolution. I quickly resorted to skimming and my eye alighted on Chinese philosophy (“True knowledge, Confucius taught, lies in the heart. He created and taught an ethical system that emphasized ‘human-heartedness,’ stressing balance in the heart”) and Dickens’s juxtaposition of facts and emotion in Hard Times.

I’d read one novel and one memoir by Godwin and was excited to learn that she had once written a wide-ranging study of the religious and literary meanings overlaid on the heart. While there are some interesting pinpricks here, the delivery is shaky: she starts off with a dull, quotation-stuffed, chronological timeline, all too thorough in its plod from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Industrial Revolution. I quickly resorted to skimming and my eye alighted on Chinese philosophy (“True knowledge, Confucius taught, lies in the heart. He created and taught an ethical system that emphasized ‘human-heartedness,’ stressing balance in the heart”) and Dickens’s juxtaposition of facts and emotion in Hard Times.

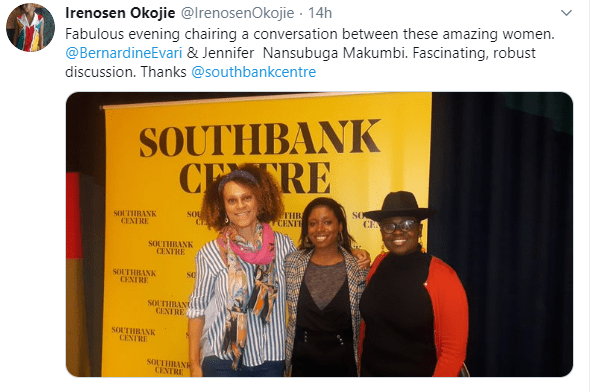

Makumbi’s novel Kintu is a sprawling family saga that has been compared to Roots, but she has recently released a collection of short stories that focus on Ugandan immigration to Britain between the 1950s and today. She envisioned Manchester Happened as “a letter back home” to tell people what it’s really like to settle in a new country, as well as a chance to reflect on the underrepresented East African immigration experience. Much of the book is drawn from her life, such as working as an airport security officer to fund her creative writing degree. Her mentor recommended that she start writing stories as a way to counterbalance the intensity of Kintu – a chance to see the beginning, middle and end as a simple arc. She assumed short stories would be easier than a novel, yet her first story took her four years to write. It is as if she can only look into her past for brief moments, anyway, she explained, so the story form has been perfect. She has deliberately avoided the negativity of many migration narratives, she said: Things have in fact gone well for her, and we’ve heard about things going wrong many times before.

Makumbi’s novel Kintu is a sprawling family saga that has been compared to Roots, but she has recently released a collection of short stories that focus on Ugandan immigration to Britain between the 1950s and today. She envisioned Manchester Happened as “a letter back home” to tell people what it’s really like to settle in a new country, as well as a chance to reflect on the underrepresented East African immigration experience. Much of the book is drawn from her life, such as working as an airport security officer to fund her creative writing degree. Her mentor recommended that she start writing stories as a way to counterbalance the intensity of Kintu – a chance to see the beginning, middle and end as a simple arc. She assumed short stories would be easier than a novel, yet her first story took her four years to write. It is as if she can only look into her past for brief moments, anyway, she explained, so the story form has been perfect. She has deliberately avoided the negativity of many migration narratives, she said: Things have in fact gone well for her, and we’ve heard about things going wrong many times before.

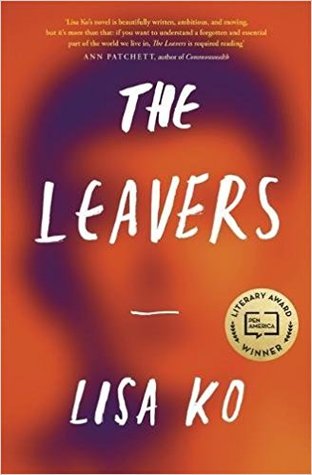

Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?

Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?