Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

Book Serendipity, March to April 2022

This is a bimonthly feature of mine. I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. Because I usually 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

(I always like hearing about your bookish coincidences, too! Laura had what she thought must be the ultimate Book Serendipity when she reviewed two novels with the same setup: Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and Last Resort by Andrew Lipstein.)

- The same sans serif font is on Sea State by Tabitha Lasley and Lean Fall Stand by Jon McGregor – both released by 4th Estate. I never would have noticed had they not ended up next to each other in my stack one day. (Then a font-alike showed up in my TBR pile, this time from different publishers, later on: What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad and When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo.)

- Kraftwerk is mentioned in The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws and How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu.

- The fact that bacteria sometimes form biofilms is mentioned in Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker and Slime by Susanne Wedlich.

- The idea that when someone dies, it’s like a library burning is repeated in The Reactor by Nick Blackburn and In the River of Songs by Susan Jackson.

- Espresso martinis are consumed in If Not for You by Georgina Lucas and Wahala by Nikki May.

- Prosthetic limbs turn up in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, and Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker.

- A character incurs a bad cut to the palm of the hand in After You’d Gone by Maggie O’Farrell and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki – I read the two scenes on the same day.

- Catfish is on the menu in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and in one story of Antipodes by Holly Goddard Jones.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

- Reading two books by a Davidson at once: Damnation Spring by Ash and Tracks by Robyn.

- There’s a character named Elwin in The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade and one called Elvin in The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- Tea is served with lemon in The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald and The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- There’s a Florence (or Flo) in Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin, These Days by Lucy Caldwell and Pictures from an Institution by Randall Jarrell. (Not to mention a Flora in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich.)

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Reading at the same time two memoirs by New Yorker writers releasing within two weeks of each other (in the UK at least) and blurbed by Jia Tolentino: Home/Land by Rebecca Mead and Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz.

- Three children play in a graveyard in Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier and Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith.

- Shalimar perfume is worn in These Days by Lucy Caldwell and The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade.

- A relative is described as “very cold” and it’s wondered what made her that way in Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso and one of the testimonies in Regrets of the Dying by Georgina Scull.

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

- From one poetry collection with references to Islam (Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire) to another (Auguries of a Minor God by Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe).

- Two children’s books featuring a building that is revealed to be a theatre: Moominsummer Madness by Tove Jansson and The Unadoptables by Hana Tooke.

- Reading two “braid” books at once: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer and French Braid by Anne Tyler.

- Protests and teargas in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Jellyfish poems in Honorifics by Cynthia Miller and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

- George Floyd’s murder is a major element in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Biography of the Month: Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

Today would have been Ali’s 76th birthday, so in honor of the occasion – and his tendency to spout off-the-cuff rhymes about his competitors’ shortfalls and his own greatness – I’ve turned his life story into a book review of sorts, in rhyming couplets.

Born into 1940s Kentucky,

this fine boy had decent luck – he

surpassed his angry, cheating father

though he shared his name; no bother –

he’d not be Cassius Clay much longer.

He knew he was so much stronger

than all those other boys. Racing

the bus with Rudy; embracing

the help of a white policeman,

his first boxing coach – this guardian

prepared him for Olympic gold

(the last time Cassius did as told?).

A self-promoter from the start, he

was no scholar but won hearts; he

hogged every crowd’s full attention

but his faults are worth a mention:

he hoarded Caddys and Royces

and made bad financial choices;

he went through one, two, three, four wives

and lots of other dames besides;

his kids – no closer than his fans –

hardly even got a chance.

Cameos from bin Laden, Trump,

Toni Morrison and more: jump

ahead and you’ll see an actor,

envoy, entrepreneur, preacher,

recognized-all-round-the-world brand

(though maybe things got out of hand).

Ali was all things to all men

and fitted in the life of ten

but though he tested a lot of walks,

mostly he just wanted to box.

The fights: Frazier, Foreman, Liston –

they’re all here, and the details stun.

Eig gives a vivid blow-by-blow

such that you will feel like you know

what it’s like to be in the ring:

dodge, jab, weave; hear that left hook sing

past your ear. Catch rest at the ropes

but don’t stay too long like a dope.

If, like Ali, you sting and float,

keep an eye on your age and bloat –

the young, slim ones will catch you out.

Bow out before too many bouts.

Ignore the signs if you so choose

(ain’t got many brain cells to lose –

these blows to the head ain’t no joke);

retirement talk ain’t foolin’ folk,

can’t you give up on earning dough

and think more about your own soul?

1968 Esquire cover. By George Lois (Esquire Magazine) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons.

Allah laid a call on your head:

To raise up the black man’s status

and ask white men why they hate us;

to resist the Vietnam draft

though that nearly got you the shaft

and lost you your name, your title

and (close) your rank as an idol.

Was it all real, your piety?

Was it worth it in society?

Nation of Islam was your crew

but sure did leave you in the stew

with that Vietcong kerfuffle

and Malcolm/Muhammad shuffle.

Through U.S. missions (after 9/11)

you explained it ain’t about heaven

and who you’ll kill to get you there;

it’s about peace, being God’s heir.

Is this story all about race?

Eig believes it deserves its place

as the theme of Ali’s life: he

was born in segregation, see,

a black fighter in a white world,

but stereotypes he hurled

right back in their faces: Uncle

Tom Negro? Naw, even punch-drunk he’ll

smash your categories and crush

your expectations. You can flush

that flat dismissal down the john;

don’t think you know what’s going on.

Dupe, ego, clown, greedy, hero:

larger than life, Jesus or Nero?

How to see both, that’s the kicker;

Eig avoids ‘good’ and ‘bad’ stickers

but shows a life laid bare and

how win and lose ain’t fair and

history is of our making

and half of legacy is faking

and all you got to do is spin

the world round ’till it lets you in.

Biography’s all ’bout the arc

and though this story gets real dark,

there’s a glister to it all the same.

A man exists beyond the fame.

What do you know beneath the name?

Less, I’d make a bet, than you think.

Come over here and take a drink:

this is long, deep, satisfying;

you won’t escape without crying.

Based on 600 interviews,

this fresh account is full of news

and fit for all, not just sports fans.

Whew, let’s give it up for Eig, man.

My rating:

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss) Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”  House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)  36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.”

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.” Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.”

Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.” The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head. Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in  This is the third collection by the Irish poet; I’d previously read her The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx. Grouped into nine thematic sections, these very short poems take the form of few-sentence aphorisms or riddles, with the titles, printed in the bottom corner, often acting as something of a punchline – especially because I had them on my e-reader and they only appeared after I’d turned the digital ‘page’. Some appear to be autobiographical, about life for a female academic. Others are political (I loved “Tenants and Landlords”), or about wolves or blackbirds. The verse in “Constructions” takes different shapes on the page. Here are “The Subject Field” and “The Actor”:

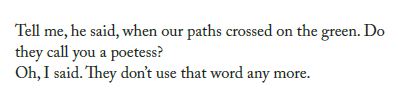

This is the third collection by the Irish poet; I’d previously read her The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx. Grouped into nine thematic sections, these very short poems take the form of few-sentence aphorisms or riddles, with the titles, printed in the bottom corner, often acting as something of a punchline – especially because I had them on my e-reader and they only appeared after I’d turned the digital ‘page’. Some appear to be autobiographical, about life for a female academic. Others are political (I loved “Tenants and Landlords”), or about wolves or blackbirds. The verse in “Constructions” takes different shapes on the page. Here are “The Subject Field” and “The Actor”:

I love the Matisse cut-outs on the cover of Draycott’s fifth collection. The title poem’s archaic spelling (“hyther,” “releyf”) contrast with its picture of a modern woman seeking respite from “the men coming on to you / the taxi drivers saying here jump in no / no you don’t need no money.” Country vs. city, public vs. private, pastoral past and technological future are some of the dichotomies the verse plays with. I enjoyed the alliteration and references to an old English herbarium, Derek Jarman and polar regions. However, it was hard to find overall linking themes to latch onto.

I love the Matisse cut-outs on the cover of Draycott’s fifth collection. The title poem’s archaic spelling (“hyther,” “releyf”) contrast with its picture of a modern woman seeking respite from “the men coming on to you / the taxi drivers saying here jump in no / no you don’t need no money.” Country vs. city, public vs. private, pastoral past and technological future are some of the dichotomies the verse plays with. I enjoyed the alliteration and references to an old English herbarium, Derek Jarman and polar regions. However, it was hard to find overall linking themes to latch onto.

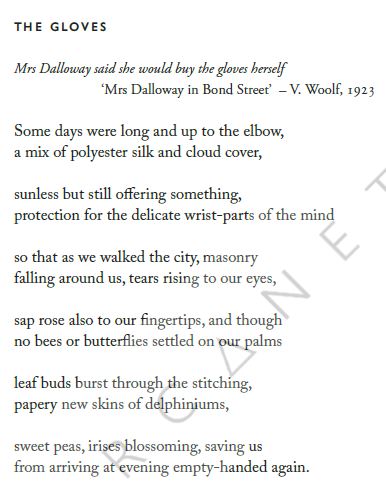

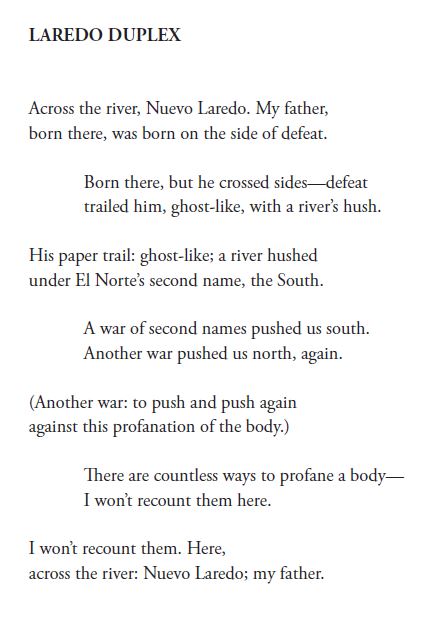

Brimming with striking metaphors and theological echoes, the first poetry collection by the Houston-based writer is an elegant record of family life on both sides of the Mexican border. “Laredo Duplex” (below) explains how violence prompted the family’s migration. “The Contract” recalls acting as a go-between for a father who didn’t speak English; in “Diáspora” the speaker is dubious about assimilation: “I am losing my brother to whiteness.” The tone is elevated and philosophical (“You take the knife of epistemology and the elegiac fork”), with ample alliteration. Flora and fauna and the Bible are common sources of unexpected metaphors. Lopez tackles big issues of identity, loss and memory in delicate verse suited to readers of Kaveh Akbar. (My full review is on

Brimming with striking metaphors and theological echoes, the first poetry collection by the Houston-based writer is an elegant record of family life on both sides of the Mexican border. “Laredo Duplex” (below) explains how violence prompted the family’s migration. “The Contract” recalls acting as a go-between for a father who didn’t speak English; in “Diáspora” the speaker is dubious about assimilation: “I am losing my brother to whiteness.” The tone is elevated and philosophical (“You take the knife of epistemology and the elegiac fork”), with ample alliteration. Flora and fauna and the Bible are common sources of unexpected metaphors. Lopez tackles big issues of identity, loss and memory in delicate verse suited to readers of Kaveh Akbar. (My full review is on

This debut collection has Rizwan juxtaposing East and West, calling out European countries for the prejudice she has experienced as a Muslim Pakistani in academia. She has also lived in the UK and USA, but mostly reflects on time spent in Germany and the Netherlands, where her imperfect grasp of the language was an additional way of standing out. “Adjunct” is the source of the cover image: she knocks and knocks for admittance, but finds herself shut out still. Rizwan takes extended metaphors from marriage, motherhood and women’s health: in “My house is becoming like my country,” she imagines her husband instituting draconian laws; in “I have found in my breast,” a visit to a doctor about a lump only exposes her own exoticism (“Basically, the Muslims are metastasizing”). In “Paris Proper,” she experiences the city differently from a friend because of the colonial history of the art. (See also

This debut collection has Rizwan juxtaposing East and West, calling out European countries for the prejudice she has experienced as a Muslim Pakistani in academia. She has also lived in the UK and USA, but mostly reflects on time spent in Germany and the Netherlands, where her imperfect grasp of the language was an additional way of standing out. “Adjunct” is the source of the cover image: she knocks and knocks for admittance, but finds herself shut out still. Rizwan takes extended metaphors from marriage, motherhood and women’s health: in “My house is becoming like my country,” she imagines her husband instituting draconian laws; in “I have found in my breast,” a visit to a doctor about a lump only exposes her own exoticism (“Basically, the Muslims are metastasizing”). In “Paris Proper,” she experiences the city differently from a friend because of the colonial history of the art. (See also

Skoulding’s collection is said to be all about Anglesey in Wales, but from that jumping-off point the poems disperse to consider maps, maritime vocabulary, seabirds, islands, tides and much more. There are also translations from the French, various commissions and collaborations, and pieces about the natural vs. the manmade. Some are in paragraph form and there’s a real variety to how lines and stanzas are laid out on the page. I especially liked “Red Squirrels in Coed Cyrnol.” I’ll read more by Skoulding.

Skoulding’s collection is said to be all about Anglesey in Wales, but from that jumping-off point the poems disperse to consider maps, maritime vocabulary, seabirds, islands, tides and much more. There are also translations from the French, various commissions and collaborations, and pieces about the natural vs. the manmade. Some are in paragraph form and there’s a real variety to how lines and stanzas are laid out on the page. I especially liked “Red Squirrels in Coed Cyrnol.” I’ll read more by Skoulding. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review. This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

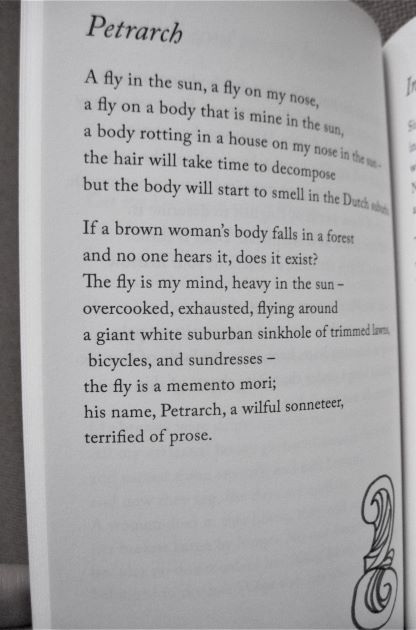

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

I approached this as a companion to

I approached this as a companion to  A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.

A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.

Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and

Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and  The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact.

The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact. This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal.

This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal. I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the

I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the

There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.

There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.