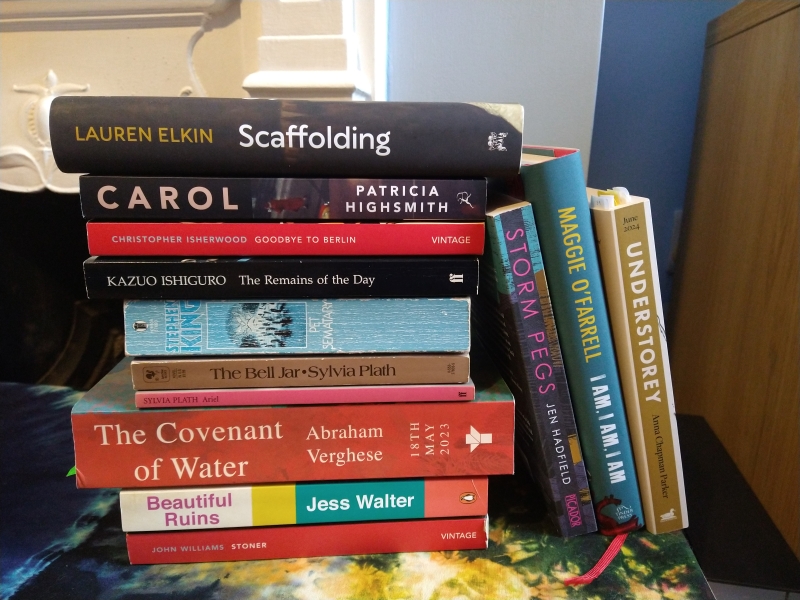

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

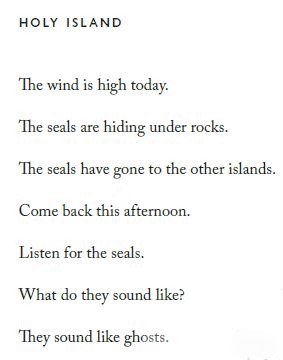

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence and Find Him! (links to my Shelf Awareness reviews) are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

July Releases: Speak to Me & The Librarianist

I didn’t expect these two novels to have anything in common, but in fact they’re both about lonely, introverted librarians who have cause to plunge into memories of a lost relationship. (They also had a couple of random tiny details in common, for which see my next installment of Book Serendipity.) Tonally, however, they couldn’t be more different, and while the one worked for me the other did not at all. You might be surprised which! Read on…

Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

I adored Cocozza’s debut, How to Be Human, so news of her follow-up was very exciting. The brief early synopses made it sound like it couldn’t be more up my street what with the theme of a woman frustrated by her husband’s obsession with his phone – I’m a smartphone refusenik and generally nod smugly along to arguments about how they’re an addiction that encourages lack of focus and time wasting. But it turns out that was only a peripheral topic; the novel is strangely diffuse and detached.

Susan is a middle-aged librarian and mother to teenage twin boys. She lives with them and her husband Kurt on a partially built estate in Berkshire full of soulless houses of various designs. Their “Beaufort” is not a happy place, and their marriage is failing, for several reasons. One is tech guru Kurt’s phone addiction. Susan refers to each new model as “Wendy,” and for her the last straw is when he checks it during the middle of sex on her 50th birthday. She joins a forum for likeminded neglected family members, and kills several Wendys by burial, washing machine, or sledgehammer.

Susan is a middle-aged librarian and mother to teenage twin boys. She lives with them and her husband Kurt on a partially built estate in Berkshire full of soulless houses of various designs. Their “Beaufort” is not a happy place, and their marriage is failing, for several reasons. One is tech guru Kurt’s phone addiction. Susan refers to each new model as “Wendy,” and for her the last straw is when he checks it during the middle of sex on her 50th birthday. She joins a forum for likeminded neglected family members, and kills several Wendys by burial, washing machine, or sledgehammer.

But as the story goes on, Kurt’s issues fade into the background and Susan becomes more obsessed with the whereabouts of a leather suitcase that went missing during their move. The case contains letters and souvenirs from her relationship with Antony, whom she met at 16. She’s convinced that Kurt is hiding it, and does ever odder things in the quest to get it back, even letting herself into their former suburban London home. Soon her mission shifts: not only does she want Antony’s letters back; she wants Antony himself.

The message seems a fairly obvious one: the characters have more immediate forms of communication at their disposal than ever before, yet are not truly communicating with each other about what they need and want from life, and allowing secrets to come between them. “We both act as if talking will destroy us, but surely silence will, more slowly, and we will be undone by all the things we leave unsaid,” Susan thinks about her marriage. Nostalgia and futurism are both held up as problematic. Fair enough.

However, Susan is unforthcoming and delusional – but not in the satisfying unreliable narrator way – and delivers this piecemeal record with such a flat affect (reminding me of no one more than the title character from Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun; Susan even says, “Why do I feel scared that someone will find me out every time I tick the box that says ‘I am not a robot’?”) that I lost sympathy early on and couldn’t care what happened. A big disappointment from my Most Anticipated list.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the proof copy for review.

The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt

Bob Comet, a retired librarian in Portland, Oregon, gets a new lease on life at age 71. One day he encounters a lost woman with dementia and/or catatonia in a 7-Eleven and, after accompanying her back to the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, decides to volunteer there. A plan to read aloud to his fellow elderly quickly backfires, but the resident curmudgeons and smart-asses enjoy his company, so he’ll just come over to socialize.

If it seems this is heading in a familiar A Man Called Ove or The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen direction, think again. Bob has a run-in with his past that leads into two extended flashbacks: one to his brief marriage to Connie and his friendship with his best man, Ethan, in 1960; the other to when he ran away by train and bus at age 11.5 and ended up in a hotel as an assistant to two eccentric actresses and their performing dogs for a few days in 1945.

If it seems this is heading in a familiar A Man Called Ove or The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen direction, think again. Bob has a run-in with his past that leads into two extended flashbacks: one to his brief marriage to Connie and his friendship with his best man, Ethan, in 1960; the other to when he ran away by train and bus at age 11.5 and ended up in a hotel as an assistant to two eccentric actresses and their performing dogs for a few days in 1945.

Imagine if Wes Anderson directed various Dickens vignettes set in the mid-20th-century Pacific Northwest – Oliver Twist with dashes of Great Expectations and Nicholas Nickleby. That’s the mood of Bob Comet’s early adventures. Witness this paragraph:

The next day Bob returned to the beach to practice his press rolls. The first performance was scheduled to take place thirty-six hours hence; with this in mind, Bob endeavored to arrive at a place where he could achieve the percussive effect without thinking of it. An hour and a half passed, and he paused, looking out to sea and having looking-out-to-sea thoughts. He imagined he heard his name on the wind and turned to find Ida leaning out the window of the tilted tower; her face was green as spinach puree, and she was waving at him that he should come up. Bob held the drum above his head, and she nodded that he should bring it with him.

(You can just picture the Anderson staginess: the long establishing shots; the jump cuts to a close-up on her face, then his; the vibrant colours; the exaggerated faces. I got serious The Grand Budapest Hotel vibes.) This whole section was so bizarre and funny that I could overlook the suspicion that deWitt got to the two-thirds point of his novel and asked himself “now what?!” The whole book is episodic and full of absurdist dialogue, and delights in the peculiarities of its characters, from Connie’s zealot father to the diner chef who creates the dubious “frizzled beef” entrée. And Bob himself? He may appear like a blank, but there are deep waters there. And his passion for books was more than enough to endear him to me:

“Bob was certain that a room filled with printed matter was a room that needed nothing.”

[Ethan:] “‘I keep meaning to get to books but life distracts me.’ ‘See, for me it’s just the opposite,’ Bob said.”

“All his life he had believed the real world was the world of books; it was here that mankind’s finest inclinations were represented.”

Weird and hilariously deadpan in just the way you’d expect from the author of The Sisters Brothers and French Exit, this was the pop of fun my summer needed. (See also Susan’s review.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Would you read one or both of these?

Booker Prize 2021: Longlist Reading and Shortlist Predictions

The 2021 Booker Prize shortlist will be announced tomorrow, September 14th, at 4 p.m. via a livestream. I’ve managed to read or skim eight of 13 from the longlist, only one of which I sought out specifically after it was nominated (An Island – the one no one had heard of; it turns out it was released by a publisher based just 1.5 miles from my home!). I review my four most recent reads below, followed by excerpts of reviews of ones I read a while ago and my brief thoughts on the rest, including what I expect to see on tomorrow’s shortlist.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Klara is an Artificial Friend purchased as part of an effort to combat the epidemic of teenage loneliness – specifically, to cheer up her owner, Josie, who suffers from an unspecified illness and is in love with her neighbour, Rick, a bright boy who remains excluded. Klara thinks of the sun as a god, praying to it and eventually making a costly bargain to try to secure Josie’s future health.

Part One’s 45 pages are slow and tedious; the backstory could have been dispensed with in five fairy tale-like pages. There’s a YA air to the story: for much of the length I might have been rereading Everything, Everything. In fact, when I saw Ishiguro introduce the novel at a Guardian/Faber launch event, he revealed that it arose from a story he wrote for children. The further I got, the more I was sure I’d read it all before. That’s because the plot is pretty much identical to the final story in Mary South’s You Will Never Be Forgotten.

Klara’s highly precise diction, referring to everyone in the third person, also gives this the feeling of translated fiction. While that is part of Ishiguro’s aim, of course – to explore the necessarily limited perspective and speech of a nonhuman entity (“Her ability to absorb and blend everything she sees around her is quite amazing”) – it makes the prose dull and belaboured. The secondary characters include various campy villains, the ‘big reveals’ aren’t worth waiting for, and the ending is laughably reminiscent of Toy Story. This took me months and months to force myself through. What a slog! (New purchase)

An Island by Karen Jennings (2019)

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Although the core action takes place in just four days, Samuel is so mentally shaky that his memories start getting mixed up with real life. We learn that he has been a father, a prisoner and a beggar. Jennings is South African, and in this parallel Africa, racial hierarchy still holds sway and a general became a dictator through a military coup. Samuel’s father was involved in the independence movement, while Samuel himself was arrested for resisting the dictator.

The novella’s themes – jealousy, mistrust, possessiveness, suspicion, and a return to primitive violence – are of perennial relevance. Somehow, it didn’t particularly resonate for me. It’s not dissimilar in style to J. M. Coetzee’s vague but brutal detachment, and it’s a highly male vision à la Doggerland. Though highly readable, it’s ultimately a somewhat thin fable with a predictable message about xenophobia. Still, I’m glad I discovered it through the Booker longlist.

My thanks to Holland House for the free copy for review.

Bewilderment by Richard Powers

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Three brides for three brothers: as Laura notes, it sounds like the setup of a folk tale, and there’s a timeless feel to this short novel set in the Punjab in the late 1920s and 1990s – it also reminded me of biblical stories like those of Jacob and Leah and David and Bathsheba. Mehar is one of three teenage girls married off to a set of brothers. The twist is that, because they wear heavy veils and only meet with their husbands at night for procreation, they don’t know which is which. Mehar is sure she’s worked out which brother is her husband, but her well-meaning curiosity has lasting consequences.

In the later storyline, a teenage addict returns from England to his ancestral estate to try to get clean before going to university and becomes captivated by the story of his great-grandmother and her sister wives, who were confined to the china room. The characters are real enough to touch, and the period and place details make the setting vivid. The two threads both explore limitations and desire, and the way the historical narrative keeps surging back in makes things surprisingly taut. See also Susan’s review. (Read via NetGalley)

Other reads, in brief:

(Links to my full reviews)

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

Here’s what I expect to still be in the running after tomorrow. Clear-eyed, profound, international; bridging historical and contemporary; much that’s unabashedly highbrow.

- Second Place by Rachel Cusk

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Bewilderment by Richard Powers

- China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

- Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund. New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey. Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble.

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble. This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like

This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like  I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.

I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.

Book III is set in a dystopian future of extreme heat, rationing and near-constant pandemics. The totalitarian state institutes ever more draconian policies, with censorship, quarantine camps and public execution of insurgents. The narrator, intellectually disabled after a childhood illness, describes the restrictions with the flat affect of the title robot from Kazuo Ishiguro’s

Book III is set in a dystopian future of extreme heat, rationing and near-constant pandemics. The totalitarian state institutes ever more draconian policies, with censorship, quarantine camps and public execution of insurgents. The narrator, intellectually disabled after a childhood illness, describes the restrictions with the flat affect of the title robot from Kazuo Ishiguro’s

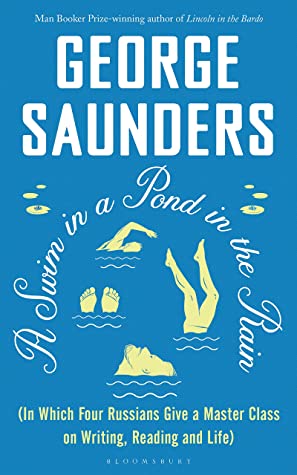

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan [Jan. 14, Chatto & Windus / May 25, Knopf] “In a world of perennial fire and growing extinctions, Anna’s aged mother … increasingly escapes through her hospital window … When Anna’s finger vanishes and a few months later her knee disappears, Anna too feels the pull of the window. … A strangely beautiful novel about hope and love and orange-bellied parrots.” I’ve had mixed success with Flanagan, but the blurb draws me and I’ve read good early reviews so far. [Library hold]

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan [Jan. 14, Chatto & Windus / May 25, Knopf] “In a world of perennial fire and growing extinctions, Anna’s aged mother … increasingly escapes through her hospital window … When Anna’s finger vanishes and a few months later her knee disappears, Anna too feels the pull of the window. … A strangely beautiful novel about hope and love and orange-bellied parrots.” I’ve had mixed success with Flanagan, but the blurb draws me and I’ve read good early reviews so far. [Library hold] The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download]

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download] The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of

The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of  Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold]

Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold] Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March. Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to

Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to  Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download]

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download] An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.”

An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.” The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner.

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner. Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,

Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,  Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending]

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending] The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued!

The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued! A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise.

A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise. Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of

Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of  Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.