Most Anticipated Books of the Second Half of 2025

My “Most Anticipated” designation sometimes seems like a kiss of death, but other times the books I choose for these lists live up to my expectations, or surpass them!

(Looking back at the 25 books I selected in January, I see that so far I have read and enjoyed 8, read but been disappointed by 4, not yet read – though they’re on my Kindle or accessible from the library – 9, and not managed to get hold of 4.)

This time around, I’ve chosen 15 books I happen to have heard about that will be released between July and December: 7 fiction and 8 nonfiction. (In release date order within genre. UK release information generally given first, if available. Note given on source if I have managed to get hold of it already.)

Fiction

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

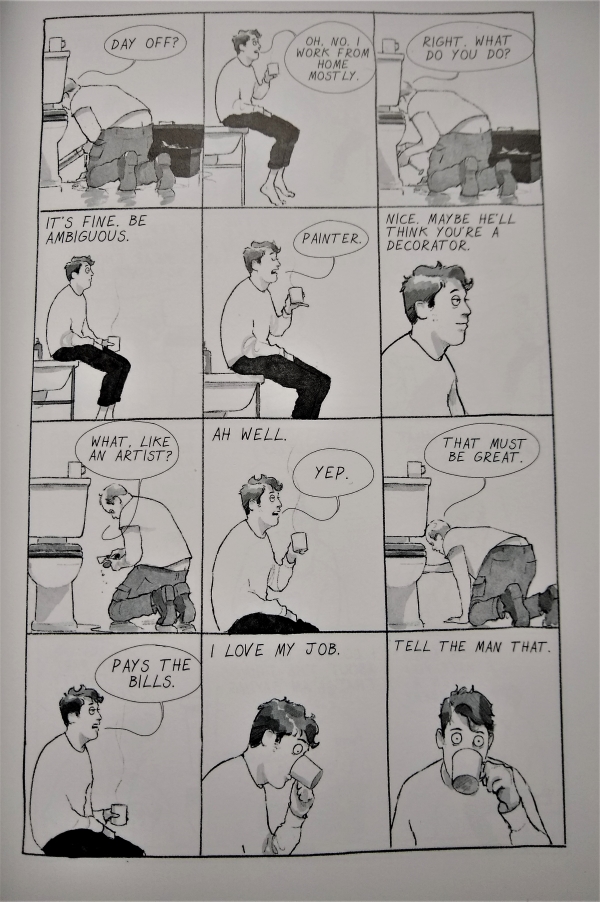

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

Nonfiction

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

As a bonus, here are two advanced releases that I reviewed early:

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists.

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists. ![]()

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans.

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans. ![]()

I can also recommend:

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, ed. Denne Michele Norris [Aug. 12, HarperOne / 25 Sept., HarperCollins] (Review to come for Shelf Awareness) ![]()

Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade [Sept. 2, Univ. of Florida Press] (Review pending for Foreword) ![]()

Which of these catch your eye? Any other books you’re looking forward to in this second half of the year?

Three May Graphic Novel Releases: Orwell, In, and Coma

These three terrific graphic novels all have one-word titles and were published on the 13th of May. Outwardly, they are very different: a biography of a famous English writer, the story of an artist looking for authentic connections, and a memoir of a medical crisis that had permanent consequences. The drawing styles are varied as well. But if the books share one thing, it’s an engagement with loneliness: It’s tempting to see the self as being pitted against the world, with illness an additional isolating force, but family, friends and compatriots are there to help us feel less alone and like we are a part of something constructive.

Orwell by Pierre Christin; illustrated by Sébastien Verdier

[Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin]

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

The book’s settings range from Spain, where Orwell went to fight in the Civil War, via a bomb shelter in London’s Underground, to the island of Jura, where he retired after the war. I particularly loved the Scottish scenery. I also appreciated the notes on where his life story entered into his fiction (especially in A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying). During World War II he joined the Home Guard and contributed to BBC broadcasting alongside T.S. Eliot. He had married Eileen, adopted a baby boy, and set up a smallholding. Even when hospitalized for tuberculosis, he wouldn’t stop typing (or smoking).

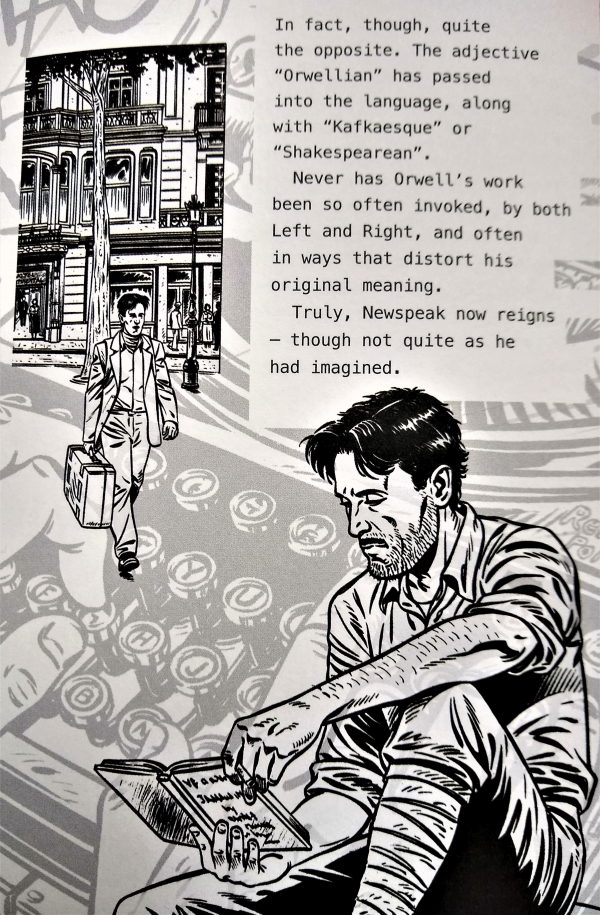

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

In by Will McPhail

Nick never knows the right thing to say. The bachelor artist’s well-intentioned thoughts remain unvoiced, such that all he can manage is small talk. Whether he’s on a subway train, interacting with his mom and sister, or sitting in a bar with a tongue-in-cheek name (like “Your Friends Have Kids” or “Gentrificchiato”), he’s conscious of being the clichéd guy who’s too clueless or pathetic to make a real connection with another human being. That starts to change when he meets Wren, a Black doctor who instantly sees past all his pretence.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Alternately laugh-out-loud funny and tender, McPhail’s debut novel is as hip as it is genuine. It’s a spot-on picture of modern life in a generic city. I especially loved the few pages when Nick is on a Zoom call with carefully ironed shirt but no trousers and the potential employers on the other end get so lost in their own jargon that they forget he’s there. His banter with Wren or with his sister reveals a lot about these characters, but there’s also an amazing 12-page wordless sequence late on that conveys so much. While I’d recommend this to readers of Alison Bechdel, Craig Thompson, and Chris Ware (and expect it to have a lot in common with Kristen Radtke’s forthcoming Seek You: A Journey through American Loneliness), it’s perfect for those brand new to graphic novels, too – a good old-fashioned story, with all the emotional range of Writers & Lovers. I hope it’ll be a wildcard entry on the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Coma by Zara Slattery

In May 2013, Zara Slattery’s life changed forever. What started as a nagging sore throat developed into a potentially deadly infection called necrotising fascitis. She spent 15 days in a medically induced coma and woke up to find that one of her legs had been amputated. As in Orwell and In, colour is used to differentiate different realms. Monochrome sketches in thick crayon illustrate her husband Dan’s diary of the everyday life that kept going while she was in hospital, yet it’s the coma/fantasy pages in vibrant blues, reds and gold that feel more real.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Meanwhile, Dan was holding down the fort, completing domestic tasks and reassuring their three children. Relatives came to stay; neighbours brought food, ran errands, and gave him lifts to the hospital. He addresses the diary directly to Zara as a record of the time she spent away from home and acknowledges that he doesn’t know if she’ll come back to them. A final letter from Zara’s nurse reveals how bad off she was, maybe more so than Dan was aware.

This must have been such a distressing time to revisit. In this interview, Slattery talks about the courage it took to read Dan’s diary even years after the fact. I admired how the book’s contrasting drawing styles recreate her locked-in mental state and her family’s weeks of waiting – both parties in limbo, wondering what will come next.

Brighton, where Slattery is based, is a hotspot of the Graphic Medicine movement spearheaded by Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor). Regular readers know how much I love health narratives, and with my keenness for graphic novels this series couldn’t be better suited to my interests.

With thanks to Myriad Editions for the free copy for review.

Read any graphic novels recently?

The Best Books from the First Half of 2020

My top 10 releases of 2020 thus far, in alphabetical order within genre (nonfiction is dominating the year for me!), are:

Fiction

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African American twins Stella and Desiree Vignes’ paths divide in 1954, with Stella passing as white. Both are desperate to escape from Mallard, Louisiana. The twins’ decisions affect the next generation, too. It’s perceptive and beautifully written, with characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent. The themes of self-reinvention and running from one’s past resonate.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African American twins Stella and Desiree Vignes’ paths divide in 1954, with Stella passing as white. Both are desperate to escape from Mallard, Louisiana. The twins’ decisions affect the next generation, too. It’s perceptive and beautifully written, with characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent. The themes of self-reinvention and running from one’s past resonate.

Writers & Lovers by Lily King: Following a breakup and her mother’s sudden death, Casey Peabody is drowning in grief and debt. Between waitressing shifts, she chips away at the novel she’s been writing for six years. Life gets complicated, especially when two love interests appear. We see this character at rock bottom but also when things start to go well at long last. I felt I knew Casey through and through, and I cheered for her. An older, sadder Sweetbitter, perhaps as written by Elizabeth Strout. It gives you all the feels, as they say.

Writers & Lovers by Lily King: Following a breakup and her mother’s sudden death, Casey Peabody is drowning in grief and debt. Between waitressing shifts, she chips away at the novel she’s been writing for six years. Life gets complicated, especially when two love interests appear. We see this character at rock bottom but also when things start to go well at long last. I felt I knew Casey through and through, and I cheered for her. An older, sadder Sweetbitter, perhaps as written by Elizabeth Strout. It gives you all the feels, as they say.

Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation. Lizzie is married with a young son and works in a NYC university library. She takes on a second job as PA to her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues. Set either side of Trump’s election, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are spot on. Could there be a more perfect book for 2020?

Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation. Lizzie is married with a young son and works in a NYC university library. She takes on a second job as PA to her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues. Set either side of Trump’s election, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are spot on. Could there be a more perfect book for 2020?

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: There’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of this novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. Themes and elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. An elegant, time-blending structure and an unrelenting course – that indifferent monolith is the perfect symbol.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: There’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of this novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. Themes and elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. An elegant, time-blending structure and an unrelenting course – that indifferent monolith is the perfect symbol.

Nonfiction

Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke: I’ve read so many doctors’ memoirs and books about death and dying; it takes a truly special one like this to stand out. Clarke specializes in palliative medicine and alternates her patients’ stories with her own in a very natural way. A major theme is her relationship with her father, who was also a doctor, and how she absorbed his lessons of empathy and dedication. A passionate and practical book, encouraging readers to be sure they and older relatives have formalized their wishes.

Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke: I’ve read so many doctors’ memoirs and books about death and dying; it takes a truly special one like this to stand out. Clarke specializes in palliative medicine and alternates her patients’ stories with her own in a very natural way. A major theme is her relationship with her father, who was also a doctor, and how she absorbed his lessons of empathy and dedication. A passionate and practical book, encouraging readers to be sure they and older relatives have formalized their wishes.

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: Gone are the days when people interested in family history had to trawl through microfilm and wait months to learn anything new; nowadays a DNA test can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. Copeland spoke to scientists and 400 laypeople who sent off saliva samples. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction.

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: Gone are the days when people interested in family history had to trawl through microfilm and wait months to learn anything new; nowadays a DNA test can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. Copeland spoke to scientists and 400 laypeople who sent off saliva samples. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction.

Greenery: Journeys in Springtime by Tim Dee: From the Cape of Good Hope to the Arctic Circle, Dee tracks the spring as it travels north. From first glimpse to last gasp, moving between his homes in two hemispheres, he makes the season last nearly half the year. His main harbingers are migrating birds, starting with swallows. The book is steeped in allusions and profound thinking about deep time and what it means to be alive in an era when nature’s rhythms are becoming distorted. A fresh, masterful model of how to write about nature.

Greenery: Journeys in Springtime by Tim Dee: From the Cape of Good Hope to the Arctic Circle, Dee tracks the spring as it travels north. From first glimpse to last gasp, moving between his homes in two hemispheres, he makes the season last nearly half the year. His main harbingers are migrating birds, starting with swallows. The book is steeped in allusions and profound thinking about deep time and what it means to be alive in an era when nature’s rhythms are becoming distorted. A fresh, masterful model of how to write about nature.

Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils by David Farrier: Blending human and planetary history, environmental realism and literary echoes, Farrier, a lecturer in English literature, tells the story of the human impact on the Earth. Each chapter is an intricate blend of fact, experience and story. We’ll leave behind massive road networks, remnants of coastal megacities, plastics, carbon and methane in the permafrost, the fossilized Great Barrier Reef, nuclear waste, and jellyfish-dominated oceans. An invaluable window onto the deep future.

Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils by David Farrier: Blending human and planetary history, environmental realism and literary echoes, Farrier, a lecturer in English literature, tells the story of the human impact on the Earth. Each chapter is an intricate blend of fact, experience and story. We’ll leave behind massive road networks, remnants of coastal megacities, plastics, carbon and methane in the permafrost, the fossilized Great Barrier Reef, nuclear waste, and jellyfish-dominated oceans. An invaluable window onto the deep future.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She makes an empirical enquiry but also attests to the personal benefits nature has. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Like Silent Spring, on which it is patterned, I can see this leading to real change.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She makes an empirical enquiry but also attests to the personal benefits nature has. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Like Silent Spring, on which it is patterned, I can see this leading to real change.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is the UK’s answer to Greta Thunberg: a leader in the youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year: of disruptions – moving house and school, of outrage at the state of the world and at individual and political indifference, of the complications of being autistic, but also of the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is the UK’s answer to Greta Thunberg: a leader in the youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year: of disruptions – moving house and school, of outrage at the state of the world and at individual and political indifference, of the complications of being autistic, but also of the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism.

The ones I own in print (not pictured: 2 read on Kindle; 1 read via the library).

The 4.5- or 5-star backlist books that I’ve read this year but haven’t yet written about on here in some way are:

The 4.5- or 5-star backlist books that I’ve read this year but haven’t yet written about on here in some way are:

- Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

- Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich

- Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields

What are some of the best books you’ve read so far this year?

What 2020 releases do I need to catch up on right away?

Adventures in Rereading: The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang

Last year I reviewed Tenth of December by George Saunders on its title date; this year I couldn’t resist rereading one of my favorites from 2014 for today’s date (which just so happens to be Bloomsday, made famous by James Joyce’s Ulysses), The Sixteenth of June.

I responded to the novel at length when it first came out. No point in reinventing the wheel, so here are mildly edited paragraphs of synopsis from my review for The Bookbag:

Maya Lang’s playful and exquisitely accomplished debut novel, set on the centenary of the original Bloomsday, transplants many characters and set pieces from Ulysses to near-contemporary Philadelphia. Don’t fret, though – even if, like me, you haven’t read Ulysses, you’ll have no trouble following the thread. In fact, Lang dedicates her book to “all the readers who never made it through Ulysses (or haven’t wanted to try).” (Though if you wish to spot parallels, pull up any online summary of Ulysses; there is also a page on Lang’s website listing her direct quotations from Joyce.)

Maya Lang’s playful and exquisitely accomplished debut novel, set on the centenary of the original Bloomsday, transplants many characters and set pieces from Ulysses to near-contemporary Philadelphia. Don’t fret, though – even if, like me, you haven’t read Ulysses, you’ll have no trouble following the thread. In fact, Lang dedicates her book to “all the readers who never made it through Ulysses (or haven’t wanted to try).” (Though if you wish to spot parallels, pull up any online summary of Ulysses; there is also a page on Lang’s website listing her direct quotations from Joyce.)

On June 16, 2004, brothers Leopold and Stephen Portman have two major commitments: their grandmother Hannah’s funeral is happening at the local synagogue in the morning; and their parents’ annual Bloomsday party will take place at their opulent Delancey Street home in the evening. Around those two thematic poles – the genuine emotions of grief and regret on the one hand, and the realm of superficial entertainment on the other – the novel expands outward to provide a nuanced picture of three ambivalent twenty-something lives.

The third side of this atypical love triangle is Nora, Stephen’s best friend from Yale – and Leo’s fiancée. Nora, a trained opera singer, is still reeling from her mother’s death from cancer one year ago. She’s been engaging in self-harming behavior, and Leo – a macho, literal-minded IT consultant – just wants to fix her. Nora and Stephen, by contrast, are sensitive, artistic souls who seem better suited to each other. Stephen, too, is struggling to find a meaning in death, but also to finish his languishing dissertation on Virginia Woolf.

Literature is almost as potent a marker of upper-class status as money here: some of the Portmans might not have even read Joyce’s masterpiece, but that doesn’t stop them name-dropping and maintaining the pretense of being well-read. While Lang might not mimic the extremes of Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness style, she prioritizes interiority over external action by using a close third-person voice that shifts between her main characters’ points of view. Their histories and thoughts are revealed mostly through interior monologues and conversations. Lang’s writing is full of mordant shards of humor; one of my favorite lines was “No one in a eulogy ever said, She watched TV with the volume on too loud.”

During my rereading, I was captivated more by the portraits of grief than by the subtle intellectual and class differences. I appreciated the characterization and the Joycean peekaboo, and the dialogue and shifts between perspectives still felt fresh and effortless. I could relate to Stephen and Nora’s feelings of being stuck and unsure how to move on in life. And the ending, which I’d completely forgotten, was perfect. I didn’t enjoy this quite as much the second time around, but it’s still a treasured signed copy on my shelf.

My original rating (June 2014):

My rating now:

Readalikes: Writers & Lovers by Lily King and The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud (my upcoming Doorstopper of the Month).

(See also my review of Lang’s recent memoir, What We Carry.)

Alas, I’ve also had a couple of failed rereading attempts recently…

Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer (2002)

I remembered this as a zany family history quest turned into fiction. A Jewish-American character named Jonathan Safran Foer travels to (fictional) Trachimbrod, Ukraine to find the traces of his ancestors and, specifically, the woman who hid his grandfather from the Nazis. I had totally forgotten about the comic narration via letters from Jonathan’s translator/tour guide, Alexander, who fancies himself a ladies’ man and whose English is full of comic thesaurus use (e.g. “Do not dub me that,” “Guilelessly yours”). This was amusing, but got to be a bit much. I’d also forgotten about the dense magic realism of the historical sections. As with A Visit from the Goon Squad, what felt dazzlingly clever on a first read (in January 2011) failed to capture me a second time. [35 pages]

I remembered this as a zany family history quest turned into fiction. A Jewish-American character named Jonathan Safran Foer travels to (fictional) Trachimbrod, Ukraine to find the traces of his ancestors and, specifically, the woman who hid his grandfather from the Nazis. I had totally forgotten about the comic narration via letters from Jonathan’s translator/tour guide, Alexander, who fancies himself a ladies’ man and whose English is full of comic thesaurus use (e.g. “Do not dub me that,” “Guilelessly yours”). This was amusing, but got to be a bit much. I’d also forgotten about the dense magic realism of the historical sections. As with A Visit from the Goon Squad, what felt dazzlingly clever on a first read (in January 2011) failed to capture me a second time. [35 pages]

Interestingly, Foer’s mother, Esther, released a memoir earlier this year, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here. It’s about the family history her son turned into quirky autofiction: a largely fruitless trip he took to Ukraine to research his maternal grandfather’s life for his Princeton thesis, and a more productive follow-up trip she took with her older son in 2009. Esther Safran Foer was born in Poland and lived in a German displaced persons camp until she and her parents emigrated to Washington, D.C. in 1949. Her father committed suicide in 1954, making him almost a belated victim of the Holocaust. The stories she hears in Ukraine – of the slaughter of entire communities; of moments of good luck that allowed her parents to, separately, survive and find each other – are remarkable, but the book’s prose, while capable, never sings. Plus, she references her son’s novel so often that I wondered why someone would read her book when they could read his instead.

Interestingly, Foer’s mother, Esther, released a memoir earlier this year, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here. It’s about the family history her son turned into quirky autofiction: a largely fruitless trip he took to Ukraine to research his maternal grandfather’s life for his Princeton thesis, and a more productive follow-up trip she took with her older son in 2009. Esther Safran Foer was born in Poland and lived in a German displaced persons camp until she and her parents emigrated to Washington, D.C. in 1949. Her father committed suicide in 1954, making him almost a belated victim of the Holocaust. The stories she hears in Ukraine – of the slaughter of entire communities; of moments of good luck that allowed her parents to, separately, survive and find each other – are remarkable, but the book’s prose, while capable, never sings. Plus, she references her son’s novel so often that I wondered why someone would read her book when they could read his instead.

On Beauty by Zadie Smith (2005)

This was an all-time favorite when it first came out. I remembered a sophisticated homage to E.M. Forster’s Howards End, featuring a biracial family in Cambridge, Mass. I remembered no specifics beyond a giant music store and (embarrassingly) an awkward sex scene. Howard Belsey’s long-distance rivalry with a fellow Rembrandt scholar gets personal when the Kipps family relocates from London to the Boston suburbs for Monty to be the new celebrity lecturer at the same college. Howard is in the doghouse with his African-American wife, Kiki, after having an affair. The Belsey boy and Kipps girl have an awkward romantic history. Zora Belsey is smitten with a lower-class spoken word poet she meets after a classical concert in the park when they pick up each other’s Discmans by accident (so dated!). All of the portraits felt like stereotypes to me, and there was so much telling, so much backstory, so many unnecessary secondary characters. Before I would have said this was my obvious Women’s Prize winner of winners, but now I have no idea what I’ll vote for. [107 pages]

This was an all-time favorite when it first came out. I remembered a sophisticated homage to E.M. Forster’s Howards End, featuring a biracial family in Cambridge, Mass. I remembered no specifics beyond a giant music store and (embarrassingly) an awkward sex scene. Howard Belsey’s long-distance rivalry with a fellow Rembrandt scholar gets personal when the Kipps family relocates from London to the Boston suburbs for Monty to be the new celebrity lecturer at the same college. Howard is in the doghouse with his African-American wife, Kiki, after having an affair. The Belsey boy and Kipps girl have an awkward romantic history. Zora Belsey is smitten with a lower-class spoken word poet she meets after a classical concert in the park when they pick up each other’s Discmans by accident (so dated!). All of the portraits felt like stereotypes to me, and there was so much telling, so much backstory, so many unnecessary secondary characters. Before I would have said this was my obvious Women’s Prize winner of winners, but now I have no idea what I’ll vote for. [107 pages]

Currently rereading: Watership Down by Richard Adams, Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn, Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama

To reread soon: Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty & Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara Kingsolver

—but the mineral-heavy imagery (“the agate cups of your palms …the bronzed lamp of my breast”) is so weirdly archaic and the vocabulary so technical that I kept thinking of the Song of Solomon. Not that there’s anything wrong with that; it’s just not the model I expected to find.

—but the mineral-heavy imagery (“the agate cups of your palms …the bronzed lamp of my breast”) is so weirdly archaic and the vocabulary so technical that I kept thinking of the Song of Solomon. Not that there’s anything wrong with that; it’s just not the model I expected to find. Meloy is from Montana and most of the 14 stories in this, her debut collection, are set in the contemporary American West among those who make their living from the outdoors, diving to work on hydroelectric dams or keeping cattle and horses. However, one of the more memorable stories, “Aqua Boulevard,” is set in Paris, where a geriatric father can’t tamp down his worries for his offspring.

Meloy is from Montana and most of the 14 stories in this, her debut collection, are set in the contemporary American West among those who make their living from the outdoors, diving to work on hydroelectric dams or keeping cattle and horses. However, one of the more memorable stories, “Aqua Boulevard,” is set in Paris, where a geriatric father can’t tamp down his worries for his offspring.

This is one of Smiley’s earlier works and feels a little generic, like she hadn’t yet developed a signature voice or themes. One summer, a 52-year-old mother of five prepares for her adult son Michael’s return from India after two years of teaching. His twin brother, Joe, will pick him up from the airport later on. Through conversations over dinner and a picnic in the park, the rest of the family try to work out how Michael has changed during his time away. “I try to accept the mystery of my children, of the inexplicable ways they diverge from parental expectations, of how, however much you know or remember of them, they don’t quite add up.” The narrator recalls her marriage-ending affair and how she coped afterwards. Michael drops a bombshell towards the end of the 91-page novella. Readable yet instantly forgettable, alas. I bought it as part of a dual volume with Good Will, which I don’t expect I’ll read. (Secondhand purchase,

This is one of Smiley’s earlier works and feels a little generic, like she hadn’t yet developed a signature voice or themes. One summer, a 52-year-old mother of five prepares for her adult son Michael’s return from India after two years of teaching. His twin brother, Joe, will pick him up from the airport later on. Through conversations over dinner and a picnic in the park, the rest of the family try to work out how Michael has changed during his time away. “I try to accept the mystery of my children, of the inexplicable ways they diverge from parental expectations, of how, however much you know or remember of them, they don’t quite add up.” The narrator recalls her marriage-ending affair and how she coped afterwards. Michael drops a bombshell towards the end of the 91-page novella. Readable yet instantly forgettable, alas. I bought it as part of a dual volume with Good Will, which I don’t expect I’ll read. (Secondhand purchase,

Miri is relieved to have her wife back when Leah returns from an extended Centre for Marine Inquiry expedition. But something went wrong with the craft while in the ocean depths and it was too late to evacuate. What happened to Leah and the rest of the small crew? Miri starts to worry that Leah – who now spends 70% of her time in the bathtub – will never truly recover. Chapters alternate between Miri describing their new abnormal and Leah recalling the voyage. As Miri tries to tackle life admin for both of them, she feels increasingly alone and doesn’t know how to deal with persistent calls from the sister of one of the crew members.

Miri is relieved to have her wife back when Leah returns from an extended Centre for Marine Inquiry expedition. But something went wrong with the craft while in the ocean depths and it was too late to evacuate. What happened to Leah and the rest of the small crew? Miri starts to worry that Leah – who now spends 70% of her time in the bathtub – will never truly recover. Chapters alternate between Miri describing their new abnormal and Leah recalling the voyage. As Miri tries to tackle life admin for both of them, she feels increasingly alone and doesn’t know how to deal with persistent calls from the sister of one of the crew members. The same intimate understanding of emotions and interactions found in

The same intimate understanding of emotions and interactions found in  Write It All Down: How to put your life on the page by Cathy Rentzenbrink [Jan. 6, Bluebird] I’ve read all of Rentzenbrink’s books, but the last few have been disappointing. Alas, this is more of a therapy session than a practical memoir-writing guide. (Full review coming later this month.)

Write It All Down: How to put your life on the page by Cathy Rentzenbrink [Jan. 6, Bluebird] I’ve read all of Rentzenbrink’s books, but the last few have been disappointing. Alas, this is more of a therapy session than a practical memoir-writing guide. (Full review coming later this month.)

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence by Gavin Francis [Jan. 13, Wellcome Collection]: A short, timely book about the history and subjectivity of recovering from illness. (Full review and giveaway coming next week.)

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence by Gavin Francis [Jan. 13, Wellcome Collection]: A short, timely book about the history and subjectivity of recovering from illness. (Full review and giveaway coming next week.)

The Store-House of Wonder and Astonishment by Sherry Rind [Jan. 15, Pleasure Boat Studio]: In her learned and mischievous fourth collection, the Seattle poet ponders Classical and medieval attitudes towards animals. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)

The Store-House of Wonder and Astonishment by Sherry Rind [Jan. 15, Pleasure Boat Studio]: In her learned and mischievous fourth collection, the Seattle poet ponders Classical and medieval attitudes towards animals. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)  Stepmotherland by Darrel Alejandro Holnes [Feb. 1, University of Notre Dame Press]: Holnes’s debut collection, winner of the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, ponders a mixed-race background and queerness through art, current events and religion. Poems take a multitude of forms; the erotic and devotional mix in provocative ways. (See my full review at

Stepmotherland by Darrel Alejandro Holnes [Feb. 1, University of Notre Dame Press]: Holnes’s debut collection, winner of the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, ponders a mixed-race background and queerness through art, current events and religion. Poems take a multitude of forms; the erotic and devotional mix in provocative ways. (See my full review at  Rise and Float: Poems by Brian Tierney [Feb. 8, Milkweed Editions]: A hard-hitting debut collection with themes of bereavement and mental illness – but the gorgeous imagery lifts it above pure melancholy. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)

Rise and Float: Poems by Brian Tierney [Feb. 8, Milkweed Editions]: A hard-hitting debut collection with themes of bereavement and mental illness – but the gorgeous imagery lifts it above pure melancholy. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)  Cost of Living: Essays by Emily Maloney [Feb. 8, Henry Holt]: Probing mental illness and pain from the medical professional’s perspective as well as the patient’s, 16 autobiographical essays ponder the value of life. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)

Cost of Living: Essays by Emily Maloney [Feb. 8, Henry Holt]: Probing mental illness and pain from the medical professional’s perspective as well as the patient’s, 16 autobiographical essays ponder the value of life. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)  Circle Way: A Daughter’s Memoir, a Writer’s Journey Home by Mary Ann Hogan [Feb. 15, Wonderwell]: A posthumous memoir of family and fate that focuses on a father-daughter pair of writers. A fourth-generation Californian, Hogan followed in her father Bill’s footsteps as a local journalist. Collage-like, the book features song lyrics and wordplay as well as family anecdotes. (See my full review at

Circle Way: A Daughter’s Memoir, a Writer’s Journey Home by Mary Ann Hogan [Feb. 15, Wonderwell]: A posthumous memoir of family and fate that focuses on a father-daughter pair of writers. A fourth-generation Californian, Hogan followed in her father Bill’s footsteps as a local journalist. Collage-like, the book features song lyrics and wordplay as well as family anecdotes. (See my full review at  Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au [Feb. 23, Fitzcarraldo Editions]: A delicate work of autofiction – it reads like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. (Full review coming up in a seasonal post.)

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au [Feb. 23, Fitzcarraldo Editions]: A delicate work of autofiction – it reads like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. (Full review coming up in a seasonal post.)  The Carriers: What the Fragile X Gene Reveals about Family, Heredity, and Scientific Discovery by Anne Skomorowsky [May 3, Columbia UP]: Blending stories and interviews with science and statistics, this balances the worldwide scope of a disease with its intimate details. (Full review coming to Foreword soon.)

The Carriers: What the Fragile X Gene Reveals about Family, Heredity, and Scientific Discovery by Anne Skomorowsky [May 3, Columbia UP]: Blending stories and interviews with science and statistics, this balances the worldwide scope of a disease with its intimate details. (Full review coming to Foreword soon.)  This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown by Taylor Harris [Jan. 11, Catapult] (Reading via Edelweiss; to review for BookBrowse)

This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown by Taylor Harris [Jan. 11, Catapult] (Reading via Edelweiss; to review for BookBrowse) Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury] (To review for Shiny New Books)

Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury] (To review for Shiny New Books)

What I Wish People Knew About Dementia by Wendy Mitchell [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury]: “When Mitchell was diagnosed with young-onset dementia at the age of fifty-eight, her brain was overwhelmed with images of the last stages of the disease – those familiar tropes, shortcuts and clichés that we are fed by the media, or even our own health professionals. … Wise, practical and life affirming, [this] combines anecdotes, research and Mitchell’s own brilliant wit and wisdom to tell readers exactly what she wishes they knew about dementia.”

What I Wish People Knew About Dementia by Wendy Mitchell [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury]: “When Mitchell was diagnosed with young-onset dementia at the age of fifty-eight, her brain was overwhelmed with images of the last stages of the disease – those familiar tropes, shortcuts and clichés that we are fed by the media, or even our own health professionals. … Wise, practical and life affirming, [this] combines anecdotes, research and Mitchell’s own brilliant wit and wisdom to tell readers exactly what she wishes they knew about dementia.” I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins [Came out in USA last year; UK release = Jan. 20, Quercus]: “Leaving behind her husband and their baby daughter, a writer gets on a flight for a speaking engagement in Reno, not carrying much besides a breast pump and a spiraling case of postpartum depression. … Deep in the Mojave Desert where she grew up, she meets her ghosts at every turn: the first love whose self-destruction still haunts her; her father, a member of the most famous cult in American history.”

I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins [Came out in USA last year; UK release = Jan. 20, Quercus]: “Leaving behind her husband and their baby daughter, a writer gets on a flight for a speaking engagement in Reno, not carrying much besides a breast pump and a spiraling case of postpartum depression. … Deep in the Mojave Desert where she grew up, she meets her ghosts at every turn: the first love whose self-destruction still haunts her; her father, a member of the most famous cult in American history.” Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim [Feb. 3, Oneworld]: “From the perfumed chambers of a courtesan school in Pyongyang to the chic cafes of a modernising Seoul and the thick forests of Manchuria, Juhea Kim’s unforgettable characters forge their own destinies as they shape the future of their nation. Immersive and elegant, firmly rooted in Korean folklore and legend, [this] unveils a world where friends become enemies, enemies become saviours, and beasts take many shapes.”

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim [Feb. 3, Oneworld]: “From the perfumed chambers of a courtesan school in Pyongyang to the chic cafes of a modernising Seoul and the thick forests of Manchuria, Juhea Kim’s unforgettable characters forge their own destinies as they shape the future of their nation. Immersive and elegant, firmly rooted in Korean folklore and legend, [this] unveils a world where friends become enemies, enemies become saviours, and beasts take many shapes.”

Theatre of Marvels by Lianne Dillsworth [April 28, Hutchinson Heinemann]: “Unruly crowds descend on Crillick’s Variety Theatre. Young actress Zillah [a mixed-race orphan] is headlining tonight. … Rising up the echelons of society is everything Zillah has ever dreamed of. But when a new stage act disappears, Zillah is haunted by a feeling that something is amiss. Is the woman in danger? Her pursuit of the truth takes her into the underbelly of the city.” (Unsolicited) [Dillsworth is Black British.]

Theatre of Marvels by Lianne Dillsworth [April 28, Hutchinson Heinemann]: “Unruly crowds descend on Crillick’s Variety Theatre. Young actress Zillah [a mixed-race orphan] is headlining tonight. … Rising up the echelons of society is everything Zillah has ever dreamed of. But when a new stage act disappears, Zillah is haunted by a feeling that something is amiss. Is the woman in danger? Her pursuit of the truth takes her into the underbelly of the city.” (Unsolicited) [Dillsworth is Black British.] The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw [Came out in USA in 2020; UK release = May 5, Pushkin]: “explores the raw and tender places where Black women and girls dare to follow their desires and pursue a momentary reprieve from being good. … With their secret longings, new love, and forbidden affairs, these church ladies are as seductive as they want to be, as vulnerable as they need to be, as unfaithful and unrepentant as they care to be, and as free as they deserve to be.”

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw [Came out in USA in 2020; UK release = May 5, Pushkin]: “explores the raw and tender places where Black women and girls dare to follow their desires and pursue a momentary reprieve from being good. … With their secret longings, new love, and forbidden affairs, these church ladies are as seductive as they want to be, as vulnerable as they need to be, as unfaithful and unrepentant as they care to be, and as free as they deserve to be.”

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols: Nichols’s ninth collection is split, like her identity, between the Guyana where she grew up and the England which she has made her home. Creole and the imagery of ghosts conjure up her coming of age in South America. She often draws on the natural world for her metaphors, and her style is characterized by alliteration and assonance. Nichols brings her adopted country to life with poems on everything from tea and the Thames to the London Underground and the Grenfell Tower fire. (My full review will appear in Issue 106 of Wasafiri literary magazine.)

Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols: Nichols’s ninth collection is split, like her identity, between the Guyana where she grew up and the England which she has made her home. Creole and the imagery of ghosts conjure up her coming of age in South America. She often draws on the natural world for her metaphors, and her style is characterized by alliteration and assonance. Nichols brings her adopted country to life with poems on everything from tea and the Thames to the London Underground and the Grenfell Tower fire. (My full review will appear in Issue 106 of Wasafiri literary magazine.)

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell.

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell.

Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This book of essays spans several decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états – including Nigeria, a nice tie-in to the Adichie. Living among the people rather than removed in some white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I’m only halfway through, but I fully expect this to stand out as one of the best travel books I’ve ever read.