Literary Wives Club: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

This is one of those classics I’ve been hearing about for decades and somehow never read – until now. Right from the start, I could spot its influence on African American writers such as Toni Morrison. Hurston deftly reproduces the all-Black milieu of Eatonville, Florida, bringing characters to life through folksy speech and tying into a venerable tradition through her lyrical prose. As the novel opens, Janie Crawford, forty years old but still a looker, sets tongues wagging when she returns to town “from burying the dead.” Her friend Pheoby asks what happened and the narrative that unfolds is Janie’s account of her three marriages.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER!}

- To protect Janie’s reputation and prospects, her grandmother, who grew up in the time of slavery, marries Janie off to an old farmer, Logan Killicks, at age 16. He works her hard and treats her no better than one of his animals.

- She then runs off with handsome, ambitious Joe Starks. [A comprehension question here: was Janie technically a bigamist? I don’t recall there being any explanation of her getting an annulment or divorce.] He opens a general store and becomes the town mayor. Janie is, again, a worker, but also a trophy wife. While the townspeople gather on the porch steps to shoot the breeze, he expects her to stay behind the counter. The few times we hear her converse at length, it’s clear she’s wise and well-spoken, but in the 20 years they are together Joe never allows her to come into her own. He also hits her. “The years took all the fight out of Janie’s face.” When Joe dies of kidney failure, she is freer than before: a widow with plenty of money in the bank.

- Nine months after Joe’s death, Janie is courted by Vergible Woods, known to all as “Tea Cake.” He is about a decade younger than her (Joe was a decade older, but nobody made a big deal out of that), but there is genuine affection and attraction between them. Tea Cake is a lovable scoundrel, not to be trusted around money or other women. They move down to the Everglades and she joins him as an agricultural labourer. The difference between this and being Killicks’ wife is that Janie takes on the work voluntarily, and they are equals there in the field and at home.

In my favourite chapter, a hurricane hits. The title comes from this scene and gives a name to Fate. Things get really melodramatic from this point, though: during their escape from the floodwaters, Tea Cake has to fend off a rabid dog to save Janie. He is bitten and contracts rabies which, untreated, leads to madness. When he comes at Janie with a pistol, she has to shoot him with a rifle. A jury rules it an accidental death and finds Janie not guilty.

I must admit that I quailed at pages full of dialogue – dialect is just hard to read in large chunks. Maybe an audiobook or film would be a better way to experience the story? But in between, Hurston’s exposition really impressed me. It has scriptural, aphoristic weight to it. Get a load of her opening and closing paragraphs:

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Here was peace. [Janie] pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

There are also beautiful descriptions of Janie’s state of mind and what she desires versus what she feels she has to settle for. “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.” She envisions happiness as sitting under a pear tree; bees buzzing in the blossom above and all the time in the world for contemplation. (It was so pleasing when I realized this is depicted on the Virago Modern Classics cover.)

I was delighted that the question of having babies simply never arises. No one around Janie brings up motherhood, though it must have been expected of her in that time and community. Her first marriage was short and, we can assume, unconsummated; her second gradually became sexless; her third was joyously carnal. However, given that both she and her mother were born of rape, she may have had traumatic associations with pregnancy and taken pains to prevent it. Hurston doesn’t make this explicit, yet grants Janie freedom to take less common paths.

What with the symbolism, the contrasts, the high stakes and the theatrical tragedy, I felt this would be a good book to assign to high school students instead of or in parallel with something by John Steinbeck. I didn’t fall in love with it in the way Zadie Smith relates in her introduction, but I did admire it and was glad to finally experience this classic of African American literature. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- A marriage without love is miserable. Marriage is not a cure for loneliness.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the unmated? Did marriage compel love like the sun the day?

(These are rhetorical questions, but the answer is NO.)

- Every marriage is different. But it works best when there is equality of labour, status and finances. Marriage can change people.

Pheoby says to Janie when she confesses that she’s thinking about marrying Tea Cake, “you’se takin’ uh awful chance.” Janie replies, “No mo’ than Ah took befo’ and no mo’ than anybody else takes when dey gits married. It always changes folks, and sometimes it brings out dirt and meanness dat even de person didn’t know they had in ’em theyselves.”

Later Janie says, “love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch. Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

This was a perfect book to illustrate the sorts of themes we usually discuss!

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in December: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (about Sylvia Plath)

August Releases: Sarah Manguso (Fiction), Sarah Moss (Memoir), and Carl Phillips (Poetry)

Today I feature a new-to-me poet and two women writers whose careers I’ve followed devotedly but whose latest books – forthright yet slippery; their genre categories could easily be reversed – I found very emotionally difficult to read. Gruelling, almost, but admirable. Many rambling thoughts ensue. Then enjoy a nice poem.

Liars by Sarah Manguso

As part of a profile of Manguso and her oeuvre for Bookmarks magazine, I wrote a synopsis and surveyed critical opinion; what follow are additional subjective musings. I’ve read six of her nine books (all but the poetry and an obscure flash fiction collection) and I esteem her fragmentary, aphoristic prose, but on balance I’m fonder of her nonfiction. Had Liars been marketed as a diary of her marriage and divorce, Manguso might have been eviscerated for the indulgence and one-sided presentation. With the thinnest of autofiction layers, is it art?

Jane recounts her doomed marriage, from the early days of her relationship with John Bridges to the aftermath of his affair and their split. She is a writer and academic who sacrifices her career for his financially risky artistic pursuits. Especially once she has a baby, every domestic duty falls to her, while he keeps living like a selfish stag and gaslights her if she tries to complain, bringing up her history of mental illness. The concise vignettes condense 14+ years into 250 pages, which is a relief because beneath the sluggish progression is such repetition of type of experiences that it could feel endless. John’s last name might as well be Doe: The novel presents him – and thus all men – as despicable and useless, while women are effortlessly capable and, by exhausting themselves, achieve superhuman feats. This is what heterosexual marriage does to anyone, Manguso is arguing. Indeed, in a Guardian interview she characterized this as a “domestic abuse novel,” and elsewhere she has said that motherhood can be unlinked from patriarchy, but not marriage.

Let’s say I were to list my every grievance against my husband from the last 17+ years: every time he left dirty clothes on the bedroom floor (which is every day); every time he loaded the dishwasher inefficiently (which is every time, so he leaves it to me); every time he failed to seal a packet or jar or Tupperware properly (which – yeah, you get the picture) – and he’s one of the good guys, bumbling rather than egotistical! And he’d have his own list for me, too. This is just what we put up with to live with other people, right? John is definitely worse (“The difference between John and a fascist despot is one of degree, not type”). But it’s not edifying, for author or reader. There may be catharsis to airing every single complaint, but how does it help to stew in bitterness? Look at everything I went through and validate my anger.

There are bright spots: Jane’s unexpected transformation into a doting mother (but why must their son only ever be called “the child”?), her dedication to her cat, and the occasional dark humour:

So at his worst, my husband was an arrogant, insecure, workaholic, narcissistic bully with middlebrow taste, who maintained power over me by making major decisions without my input or consent. It could still be worse, I thought.

Manguso’s aphoristic style makes for many quotably mordant sentences. My feelings vacillated wildly, from repulsion to gung-ho support; my rating likewise swung between extremes and settled in the middle. I felt that, as a feminist, I should wholeheartedly support a project of exposing wrongs. It’s easy to understand how helplessness leads to rage, and how, considering sunk costs, a partner would irrationally hope for a situation to improve. So I wasn’t as frustrated with Jane as some readers have been. But I didn’t like the crass sexual language, and on the whole I agreed with Parul Sehgal’s brilliant New Yorker review that the novel is so partial and the tone so astringent that it is impossible to love. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

And a quote from the Moss memoir (below) to link the two books: “Homes are places where vulnerable people are subject to bullying, violence and humiliation behind closed doors. Homes are places where a woman’s work is never done and she is always guilty.”

20 Books of Summer, #19:

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I’ve reviewed this memoir for Shelf Awareness (it’s coming out in the USA from Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 22nd) so will only give impressions, in rough chronological order:

Sarah Moss returns to nonfiction – YES!!!

Oh no, it’s in the second person. I’ve read too much of that recently. Fine for one story in a collection. A whole book? Not so sure. (Kirsty Logan got away with it, but only because The Unfamiliar is so short and meant to emphasize how matrescence makes you other.)

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

Once she starts discussing her childhood reading – what it did for her then and how she views it now – the book really came to life for me. And she very effectively contrasts the would-be happily ever after of generally getting better after eight years of disordered eating with her anorexia returning with a vengeance at age 46 – landing her in A&E in Dublin. (Oh! when she reads War and Peace over and over on a hospital bed and defiantly uses the clean toilets on another floor.) This crisis is narrated in the third person before a return to second person.

The tone shifts throughout the book, so that what threatens to be slightly cloying in the childhood section turns academically curious and then, somehow, despite the distancing pronouns, intimate. So much so that I found myself weeping through the last chapters over this lovely, intelligent woman’s ongoing struggles. As an overly cerebral person who often thinks it’s pesky to have to live in a body, I appreciated her probing of the body/mind divide; and as she tracks where her food issues came from, I couldn’t help but think about my sister’s years of eating disorders and my mother’s fear that it was all her fault.

Beyond Moss’s usual readers, I’d also recommend this to fans of Laura Freeman’s The Reading Cure and Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place.

Overall: shape-shifting, devastating, staunchly pragmatic. I’m not convinced it all hangs together (and I probably would have ended it at p. 255), but it’s still a unique model for transmuting life into art. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Will I remember individual poems? Unlikely. But the sense of chilly, clear-eyed reflection, yes. (Sample poem below) ![]()

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

Record of Where a Wind Was

Wave-side, snow-side,

little stutter-skein of plovers

lifting, like a mind

of winter—

We’d been walking

the beach, its unevenness

made our bodies touch,

now and then, at

the shoulders mostly,

with that familiarity

that, because it sometimes

includes love, can

become confused with it,

though they remain

different animals. In my

head I played a game with

the waves called Weapon

of Choice, they kept choosing

forgiveness, like the only

answer, as to them

it was, maybe. It’s a violent

world. These, I said, I choose

these, putting my bare hands

through the air in front of me.

Any other August releases you’d recommend?

20 Books of Summer, 11–13: Campbell, Julavits, Lu

Two solid servings of women’s life writing plus a novel about a Chinese woman stuck in roles she’s not sure she wants anymore.

Thunderstone: A true story of losing one home and discovering another by Nancy Campbell (2022)

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

The title refers to a fossil that has been considered a talisman in various cultures, and she needed the good luck during a period that involved accidental carbon monoxide poisoning and surgery for an ovarian abnormality (but it didn’t protect her books, which were all destroyed in a leaking shipping container – the horror!). I most enjoyed the longer entries where she muses on “All the potential lives I moved on from” during 20 years in Oxford and elsewhere, which makes me think that I would have preferred a more traditional memoir by her. Covid narratives feel really dated now, unfortunately. (New (bargain) purchase from Hungerford Bookshop with birthday voucher)

Directions to Myself: A Memoir by Heidi Julavits (2023)

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Mostly the memoir takes readers through everyday conversations the author has with friends and family about situations of inequality or harassment. Through her words she tries to gently steer her son towards more open-minded ideas about gender roles. She also entrances him and his sleepover friends with a real-life horror story about being chased through the French countryside by a man in a car. The tenor of her musings appealed to me, but already the details are fading. I suspect this will mean much more to a parent.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

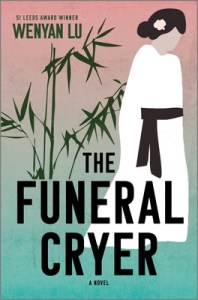

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu (2023)

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy.

#ReadingtheMeow2024 and 20 Books of Summer, 2: Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy

Reviews of books about cats have been a standard element on my blog over the years, and the second annual Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri, was a good excuse to pick up some more. Tomorrow I’ll review two cat-themed novels; today I have a 2002 memoir that I have been meaning to read for ages.

I discovered Piercy through her poetry, then read Woman on the Edge of Time, a feminist classic that contrasts utopian and dystopian views of the future. Like May Sarton (whom Piercy knew), she devotes equal energy to both fiction and poetry and is an inveterate cat lady. Piercy is still publishing and blogging at 88; I have much to catch up on from her back catalogue. A précis of her life is almost stranger than fiction: she grew up in poverty in Detroit, joining a teen gang and discovering her sexuality first with other girls (“The first time I had an orgasm—I was eleven—I was astonished and also I had a feeling of recognition. Of course, that’s it. As if that was what I had been expecting or looking for”) then with men; had a couple abortions, including one self-administered, then got sterilized; honed her writing craft at college; married three times – briefly to a Frenchman, an unhappy open arrangement, and now for 40+ years to fellow writer Ira Wood; and wrote like a dervish yet has remained on the periphery of the literary establishment and thus struggled financially.

Political activism has been a constant for Piercy, whether protesting the Vietnam War or supporting women’s reproductive rights. She and Wood also nurtured a progressive Jewish community around their Cape Cod home. Again like Sarton, she has always embraced the term feminist but been more resistant to queerness. A generational thing, perhaps; nowadays we would surely call Piercy bisexual or at least sexually fluid, but she’s more apt to dismiss her teen girlfriends and her later affairs with women as a phase. The personal life and career mesh here, though there is more of a focus on the former, such that I haven’t really gotten a clear idea of which of her novels I might want to try. Each chapter ends with one of her poems (wordy, autobiographical free verse), giving a flavour of her work in other genres. She portrays herself as a nomad who wandered various cities before settling into an unexpectedly homely and seasonal existence: “I am a stray cat who has finally found a good home.”

I admired Piercy’s self-knowledge here: her determination to write (including to keep her late mother alive in her) and to preserve the solitude necessary to her work –

I know I am an intense, rather angular passionate woman, not easy to like, not easy to live with, even for myself. Convictions, causes jostle in me. My appetites are large. I have learned to protect my work time and my privacy fiercely. I have been a better writer than a person, and again and again I made that choice. Writing is my core. I do not regret the security I have sacrificed to serve it.

and her conviction that motherhood was not for her –

I did not want children. I never felt I would be less of a woman, but I feared I would be less of a writer if I reproduced. I didn’t feel anything special about my genetic composition warranted replicating it. … I liked many of my friends’ children as they grew older: I was a good aunt. But I never desired to possess them or have one of my own. … I have never regretted staying childless. My privacy, my time for work … are precious. I feel my life is full enough.

“There were no role models for a woman like me,” she felt at the end of college, but she can in her turn be a role model of the female artist’s life, socially engaged and willing to take risks.

As to the title: There is, of course, special delight here for cat lovers. Piercy has had cats since she was a child, and in the Cape Cod era has usually kept a band of five or so. In the interludes we meet some true characters: Arofa the Siamese, Cho-Cho who lived to 21, mother and son Dinah and Oboe, alpha male Jim Beam, and many more. Of course, they age and fall ill and there are some goodbye scenes. She mostly describes these unsentimentally – if you’ve read Doris Lessing on cats, I’d say the attitude is similar. There are extremes of both love and despair: she licks a kitten to bond with her; she euthanizes one beloved cat herself. She wrote this memoir at 65 and felt that her cats were teaching her how to age.

There is a sadness to living with old cats; also a comfort and pleasure, for you know each other thoroughly and the trust is almost absolute. … The knowledge of how much I will miss them is always with me, but so is the sense of my own time flowing out, my life passing and the necessity to value it as I value them. Old cats are precious.

Even those unfamiliar with Piercy’s work might enjoy reading a perspective on the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s. This was right up my street because of her love of cats, her defence of the childfree life, and her interest in identity and memory. Because she doesn’t talk in depth about her oeuvre, you needn’t have read anything else of hers to appreciate reading this. I hope you have a cat who will nap on your lap as you do so. (Secondhand, a gift from my wish list) ![]()

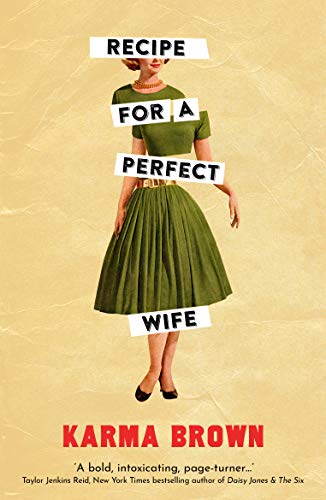

Literary Wives Club: Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown (2019)

{SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!}

Canadian author Karma Brown’s fifth novel features two female protagonists who lived in the same house in different decades. The dual timeline, which plays out in alternating chapters, contrasts the mid-1950s and late 2010s to ask 1) whether the situation of women has really improved and 2) if marriage is always and inevitably an oppressive force.

Nellie Murdoch loves cooking and gardening – great skills for a mid-twentieth-century housewife – but can’t stay pregnant, which provokes the anger of her abusive husband, Richard. To start with, Alice Hale can’t cook or garden for toffee and isn’t sure she wants a baby at all, but as she reads through Nellie’s unsent letters and recipes, interspersed with Ladies’ Home Journal issues in the boxes in the basement, she starts to not just admire Nellie but emulate her. She’s keeping several things from her husband Nate: she was fired from her publicist job after a pre-#MeToo scandal involving a handsy male author, she’s had an IUD fitted, and she’s made zero progress on the novel she’s supposed to be writing. But Nellie’s correspondence reveals secrets that inspire Alice to compose Recipe for a Perfect Wife.

The chapter epigraphs, mostly from period etiquette and relationship guides for young wives, provide ironic commentary on this pair of not-so-perfect marriages. Brown has us wondering how closely Alice will mirror Nellie’s trajectory (aborting her pregnancy? poisoning her husband?). There were clichéd elements, such as Richard’s adultery, glitzy New York City publishing events, Alice’s quirky-funny friend, and each woman having a kindly elderly (maternal) neighbour who looks out for her and gives her valuable advice. I felt uncomfortable with how Nellie’s mother’s suicide makes it seem like Nellie’s radical acts are borne out of inherited mental illness rather than a determination to make her own path.

Often, I felt Brown was “phoning it in,” if that phrase means anything to you. In other words, playing it safe and taking an easy and previously well-trodden path. Parallel stories like this can be clever, or can seem too simple and coincidental. However, I can affirm that the novel is highly readable and has vintage charm. I always enjoy epistolary inclusions like letters and recipes, and it was intriguing to see how Nellie uses her garden herbs and flowers for pharmaceutical uses. Our first foxglove just came into flower – eek! (Kindle purchase) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- Being a wife does not have to mean being a housewife. (It also doesn’t have to mean being a mother, if you don’t want to be one.)

- Secrets can be lethal to a marriage. Even if they aren’t literally so, they’re a really bad idea.

This was, overall, a very bleak picture of marriage. In the 1950s strand there is a scene of marital rape – one of two I’ve read recently, and I find these particularly difficult to take. Alice’s marriage might not have blown up as dramatically, but still doesn’t appear healthy. She forced Nate to choose between her and the baby, and his job promotion in California. The fallout from that ultimatum is not going to make for a happy relationship. I almost thought that Nellie wields more power. However, both women get ahead through deception and manipulation. I think we are meant to cheer for what they achieve, and I did for Nellie’s revenge at Richard’s vileness, but Alice I found brattish and calculating.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

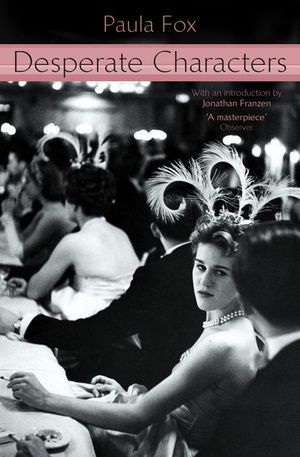

Other covers feature a cat, which is probably why this was on my radar. Don’t expect a cat lover’s book, though. The cat simply provides the opening incident. Sophie Bentwood is a forty-year-old underemployed translator; she doesn’t really need to work because her lawyer husband Otto keeps them in comfort. Feeding a feral cat, she is bitten savagely on the hand and over the next several days puts off seeking medical attention, wanting to stay in uncertainty rather than condemn herself to rounds of shots – and the cat to possible euthanasia. Both she and Otto live in this state of inertia. They were never able to have children but couldn’t take the step of adopting; Sophie had an affair but couldn’t leave Otto to commit elsewhere.

Other covers feature a cat, which is probably why this was on my radar. Don’t expect a cat lover’s book, though. The cat simply provides the opening incident. Sophie Bentwood is a forty-year-old underemployed translator; she doesn’t really need to work because her lawyer husband Otto keeps them in comfort. Feeding a feral cat, she is bitten savagely on the hand and over the next several days puts off seeking medical attention, wanting to stay in uncertainty rather than condemn herself to rounds of shots – and the cat to possible euthanasia. Both she and Otto live in this state of inertia. They were never able to have children but couldn’t take the step of adopting; Sophie had an affair but couldn’t leave Otto to commit elsewhere. I’m almost tempted to mark this as an R.I.P. read, because it’s very dark indeed. Like

I’m almost tempted to mark this as an R.I.P. read, because it’s very dark indeed. Like

Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.

Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.

“Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times.

“Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times. And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

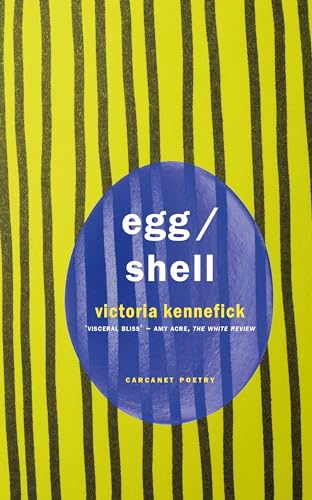

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,  This is Mann’s second collection, after

This is Mann’s second collection, after