Be(com)ing an ‘Expert’ on Postpartum Depression for #NonficNov

This Being/Becoming/Asking the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Rennie of What’s Nonfiction.

I’m also counting this as the first entry in my new “Three on a Theme” series, where I’ll review three books that have something significant in common and tell you which one to pick up if you want to read into the topic for yourself. I have another medical-themed one lined up for this Friday as a second ‘Being the Expert’ entry.

I never set out to read several memoirs of women’s experience of postpartum depression this year; it sort of happened by accident. I started with the graphic memoir and then chanced upon a recent pair of traditional memoirs published in the UK – in fact, I initially pitched them as a dual review to the TLS, but they’d already secured a reviewer for one of the books.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

Cho alternates between her time on the New Bridge ward – writing in a notebook, trying to act normal whenever James visited, expressing milk from painfully swollen breasts, and interacting with her fellow patients with all their quirks – and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown. Her Kentucky childhood was marked by her mathematician father’s detachment and the sense that she and her brother were together “in the trenches,” pitted against the world. In her twenties she worked in a New York City corporate law firm and got caught up in an abusive relationship with a man she moved to Hong Kong to be with. All along she weaves in her family’s history and Korean sayings and legends that explain their values.

Twelve days. That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory – a terrifying time when she questioned her sanity and whether she was cut out for motherhood. “Koreans believe that happiness can only tempt the fates and that any happiness must be bought with sorrow,” she writes. She captures both extremes, of suffering and joy, in this vivid account.

My rating:

What Have I Done? An honest memoir about surviving postnatal mental illness by Laura Dockrill

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

My rating:

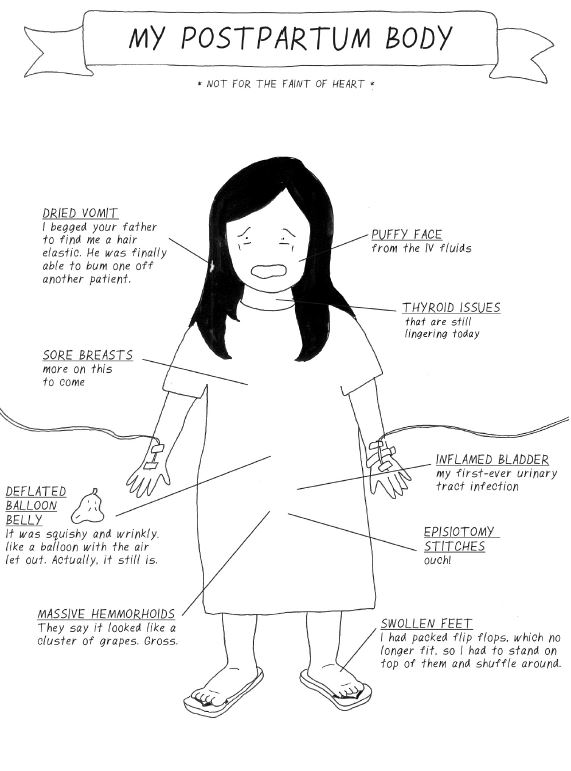

Dear Scarlet: The Story of My Postpartum Depression by Teresa Wong (2019)

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

For Wong, a combination of antidepressants, therapy, a postnatal doula, an exercise class, her mother’s help, and her husband’s constant support got her through, and she knows she’s lucky to have had a fairly mild case and to have gotten assistance early on. I loved the “Not for the Faint of Heart” anatomical spreads and the reflections on her mother’s tough early years after arriving in Canada from China.

The drawing and storytelling style is similar to that of Sarah Laing and Debbie Tung. The writing is more striking than the art, though, so I hope that with future work the author will challenge herself to use more color and more advanced designs (from her Instagram page it looks like she is heading that way).

My rating:

My thanks to publicist Beth Parker for the free e-copy for review.

What I learned:

All three authors emphasize that motherhood does not always come naturally; “You might not instantly love your baby,” as Dockrill puts it. There might be a feeling of detachment – from the baby and/or from one’s new body. They all note that postpartum depression is common and that new mothers should not be ashamed of seeking help from medical professionals, baby nurses, family members and any other sources of support.

These two passages were representative for me:

Cho: “I don’t feel a rush of love or an overwhelming weight of responsibility, emotions that I’d been expecting. Instead, I felt curious, like I’d just been introduced to a stranger. He was a creature, an idea, not even human yet, just a being, a life. … I’d thought I would reclaim my body after birth, but instead, it was now a tool, something to sustain life.”

Dockrill: “If childbirth and motherhood are the most natural, universal, common things in the world, the things that women have been doing since the beginning of time, then why does nobody tell us that there’s a good chance that you might not feel like yourself after you have a baby? That you might even lose your head? That you might not ever come back?”

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

Nobody Told Me by Hollie McNish, one of my current bedside books, also deals with complicated pregnancy emotions and the chaotic early months of motherhood.

If you read just one, though… Make it Inferno by Catherine Cho.

Can you see yourself reading any of these books?

Autumn Reading: The Pumpkin Eater and More

I’ve been gearing up for Novellas in November with a few short autumnal reads, as well as some picture books bedecked with fallen leaves, pumpkins and warm scarves.

An Event in Autumn by Henning Mankell (2004)

[Translated from the Swedish by Laurie Thompson, 2014]

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

My first and probably only Mankell novel; I have a bad habit of trying mystery series and giving up after one book – or not even making it through a whole one. This was written for a Dutch promotional deal and falls chronologically between The Pyramid and The Troubled Man, making it #9.5 in the Wallander series. It opens in late October 2002. After 30 years as a police officer, Kurt Wallander is interested in living in the countryside instead of the town-center flat he shares with his daughter Linda, also a police officer. A colleague tells him about a house in the country owned by his wife’s cousin and Wallander goes to have a look.

Of course things aren’t going to go smoothly with this venture. You have to suspend disbelief when reading about the adventures of investigators; it’s like they attract corpses. So it’s not much of a surprise that while he’s walking the grounds of this house he finds a human hand poking out of the soil, and eventually the remains of a middle-aged couple are unearthed. The rest of the book is about finding out what happened on the property at the time of the Second World War. Wallander says he doesn’t believe in ghosts, but victims of wrongful death are as persistent as ghosts: they won’t be ignored until answers are found.

This was a quick and easy read, but nothing about it (setting, topics, characterization, prose) made me inclined to read further in the author’s work.

My rating:

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer (1962)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

(Classic of the Month, #1)

Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, they’re building a glass tower as their countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood.

An excellent 2011 introduction by Daphne Merkin reveals how autobiographical this seventh novel was for Mortimer. But her backstory isn’t a necessary prerequisite for appreciating this razor-sharp period piece. You get a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility and chafing at the thought that she’s had no choice in what life has dealt her. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humor and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind. I was reminded of Janice Galloway’s The Trick Is to Keep Breathing and Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. If you’re still looking for ideas for Novellas in November, I recommend it highly.

My rating:

Snow in Autumn by Irène Némirovsky (1931)

[Translated from the French by Sandra Smith, 2007]

(Classic of the Month, #2)

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

I have a copy of Suite Française, Némirovsky’s renowned posthumous classic, in a box in America, but have never gotten around to reading it. This early tale of the Karine family, forced into exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution, draws on the author’s family history. The perspective is that of the family’s old nanny, Tatiana Ivanovna, who guards the house for five months after the Karines flee and then, joining them in Paris after a shocking loss, longs for the snows of home. “Autumn is very long here … In Karinova, it’s already all white, of course, and the river will be frozen over.” Nostalgia is not as innocuous as it might seem, though. This gloomy short piece brought to mind Gustave Flaubert’s story “A Simple Heart.” I wouldn’t say I’m taken by Némirovsky’s style thus far; in fact, the frequent ellipses drove me mad! The other novella in my paperback is Le Bal, which I’ll read next month.

My rating:

Plus a quartet of children’s picture books from the library:

Pumpkin Soup by Helen Cooper: A cat, a squirrel and a duck live together in a teapot-shaped cabin in the woods. They cook pumpkin soup and make music in perfect harmony, each cheerfully playing their assigned role, until the day Duck decides he wants to be the one to stir the soup. A vicious quarrel ensues, and Duck leaves. Nothing is the same without the whole trio there. After some misadventures, when the gang is finally back together, they’ve learned their lesson about flexibility … or have they? Adorably mischievous.

Moomin and the Golden Leaf by Richard Dungworth: Beware: this is not actually a Tove Jansson plot, although her name is, misleadingly, printed on the cover (under tiny letters “Based on the original stories by…”). Autumn has come to Moominvalley. Moomin and Sniff find a golden leaf while they’re out foraging. He sets out to find the golden tree it must have come from, but the source is not what he expected. Meanwhile, the rest are rehearsing a play to perform at the Autumn Ball before a seasonal feast. This was rather twee and didn’t capture Jansson’s playful, slightly melancholy charm.

Little Owl’s Orange Scarf by Tatyana Feeney: Ungrateful Little Owl thinks the orange scarf his mother knit for him is too scratchy. He tries “very hard to lose his new scarf” and finally manages it on a trip to the zoo. His mother lets him choose his replacement wool, a soft green. I liked the color blocks and the simple design, and the final reveal of what happened to the orange scarf is cute, but I’m not sure the message is one to support (pickiness vs. making do with what you have).

Christopher Pumpkin by Sue Hendra and Paul Linnet: The witch of Spooksville needs help preparing for a big party, so brings a set of pumpkins to life. Something goes a bit wrong with the last one, though: instead of all things ghoulish, Christopher Pumpkin loves all things fun. He bakes cupcakes instead of stirring gross potions and strums a blue ukulele instead of inducing screams. The witch threatens to turn Chris into soup if he can’t be scary. The plan he comes up with is the icing on the cake of a sweet, funny book delivered in rhyming couplets. Good for helping kids think about stereotypes and how we treat those who don’t fit in.

Have you read any autumn-appropriate books lately?

20 Books of Summer, #9–11: Asimov, St. Aubyn, Weiss

My summer reading has been picking up and I have a firm plan – I think – for the rest of the foodie books that will make up my final 20. I’m reading two more at the moment: a classic with an incidental food-themed title and a work of American history via foodstuffs. Today I have a defense of drinking wine for pleasure; a novel about inheritance and selfhood, especially for mothers; and a terrific foodoir set in Berlin, New York City and rural Italy.

How to Love Wine: A Memoir and Manifesto by Eric Asimov (2012)

(20 Books of Summer, #9) Asimov may be the chief wine critic for the New York Times, but he’s keen to emphasize that he’s no wine snob. After decades of drinking it, he knows what he appreciates and prefers small-batch to mass market wine, but he’d rather that people find what they enjoy rather than chase after the expensive bottles they feel they should like. He finds tasting notes and scores meaningless and is more interested in getting people into wine simply for the love of it – not as a status symbol or a way of showing off arcane knowledge.

(20 Books of Summer, #9) Asimov may be the chief wine critic for the New York Times, but he’s keen to emphasize that he’s no wine snob. After decades of drinking it, he knows what he appreciates and prefers small-batch to mass market wine, but he’d rather that people find what they enjoy rather than chase after the expensive bottles they feel they should like. He finds tasting notes and scores meaningless and is more interested in getting people into wine simply for the love of it – not as a status symbol or a way of showing off arcane knowledge.

Like Anthony Bourdain (see my review of Kitchen Confidential), Asimov was drawn into foodie culture by one memorable meal in France. He’d had a childhood sweet tooth and was a teen beer drinker, but when he got to grad school in Austin, Texas an $8 bottle of wine from a local Whole Foods was an additional awakening. Following in his father’s footsteps in journalism and moving from Texas to Chicago back home to New York City for newspaper editing jobs, he had occasional epiphanies when he bought a nice bottle of wine for his parents’ anniversary and took a single wine appreciation course. But his route into writing about wine was sideways, through a long-running NYT column about local restaurants.

I might have liked a bit more of the ‘memoir’ than the ‘manifesto’ of the subtitle: Asimov makes the same argument about accessibility over and over, yet even his approachable wine attitude was a little over my head. I can’t see myself going to a tasting of 20–25 wines at a time, or ordering a case of 12 wines to sample at home. Not only can I not tell Burgundy from Bordeaux (his favorites), I can’t remember if I’ve ever tried them. I’m more of a Sauvignon Blanc or Chianti gal. Maybe the Wine for Dummies volume I recently picked up from a Little Free Library is more my speed.

Source: Free from a neighbor

My rating:

Mother’s Milk by Edward St Aubyn (2006)

(20 Books of Summer, #10; A buddy read with Annabel, who has also reviewed the first three books here and here as part of her 20 Books of Summer.) I’ve had mixed luck with the Patrick Melrose books thus far: Book 1, Never Mind, about Patrick’s upbringing among the badly-behaving rich in France and his sexual abuse by his father, was too acerbic for me, and I didn’t make it through Book 3, Some Hope. But Book 2, Bad News, in which Patrick has become a drug addict and learns of his father’s death, hit the sweet spot for black comedy.

(20 Books of Summer, #10; A buddy read with Annabel, who has also reviewed the first three books here and here as part of her 20 Books of Summer.) I’ve had mixed luck with the Patrick Melrose books thus far: Book 1, Never Mind, about Patrick’s upbringing among the badly-behaving rich in France and his sexual abuse by his father, was too acerbic for me, and I didn’t make it through Book 3, Some Hope. But Book 2, Bad News, in which Patrick has become a drug addict and learns of his father’s death, hit the sweet spot for black comedy.

Mother’s Milk showcases two of St. Aubyn’s great skills: switching effortlessly between third-person perspectives, and revealing the psychology of his characters. It opens with a section from the POV of Patrick’s five-year-old son, Robert, a perfect link back to the child’s-eye view of Book 1 and a very funny introduction to this next generation of precocious mimics. The perspective is shared between Robert, Patrick, his wife Mary, and their younger son Thomas across four long chapters set in the Augusts of 2000–2003.

Patrick isn’t addicted to heroin anymore, but he still relies on alcohol and prescription drugs, struggles with insomnia and is having an affair. Even if he isn’t abusive or neglectful like his own parents, he worries he’ll still be a destructive influence on his sons. Family inheritance – literal and figurative – is a major theme, with Patrick disgruntled with his very ill mother, Eleanor, for being conned into leaving the home in France to a New Age organization as a retreat center. “What I really loathe is the poison dripping from generation to generation,” Patrick says – “the family’s tropical atmosphere of unresolved dependency.” He mentally contrasts Eleanor and Mary, the former so poor a mother and the latter so devoted to her maternal role that he feels there’s no love left for himself from either.

I felt a bit trapped during unpleasant sections about Patrick’s lust, but admired the later focus on the two mothers and their loss of sense of self, Eleanor because of her dementia and Mary because she has been subsumed in caring for Thomas. I didn’t quite see how all the elements were meant to fit together, particularly the disillusioning trip to New York City, but the sharp writing and observations were enough to keep me going through this Booker-shortlisted novella. I’ll have to get Book 5 out from the library to see how St. Aubyn tied everything up.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

My Berlin Kitchen: Adventures in Love and Life by Luisa Weiss (2012)

(20 Books of Summer, #11) Blog-to-book adaptations can be hit or miss; luckily, this one joins Julie Powell’s Julie and Julia and Molly Wizenberg’s A Homemade Life in the winners column. Raised in Berlin and Boston by her American father and Italian mother, Weiss felt split between her several cultures and languages. While she was working as a cookbook editor in New York City, she started a blog, The Wednesday Chef, as a way of working through the zillions of recipes she’d clipped from here and there, and of reconnecting with her European heritage: “when I came down with a rare and chronic illness known as perpetual homesickness, I knew the kitchen would be my remedy.”

(20 Books of Summer, #11) Blog-to-book adaptations can be hit or miss; luckily, this one joins Julie Powell’s Julie and Julia and Molly Wizenberg’s A Homemade Life in the winners column. Raised in Berlin and Boston by her American father and Italian mother, Weiss felt split between her several cultures and languages. While she was working as a cookbook editor in New York City, she started a blog, The Wednesday Chef, as a way of working through the zillions of recipes she’d clipped from here and there, and of reconnecting with her European heritage: “when I came down with a rare and chronic illness known as perpetual homesickness, I knew the kitchen would be my remedy.”

After a bad breakup (for which she prescribes fresh Greek salad, ideally eaten outside), she returned to Berlin and unexpectedly found herself back in a relationship with Max, whom she’d met in Paris nearly a decade ago but drifted away from. She realized they were meant to be together when he agreed that potato salad should be dressed with oil and vinegar rather than mayonnaise. After a tough year for Weiss as she readjusts to Berlin’s bitter winters and lack of bitter greens, the book ends with the lovely scene of their rustic Italian wedding.

Weiss writes with warmth and candor and gets the food–life balance just right. I found a lot to relate to here (“I couldn’t ever allow myself to think about how annoying airports were, how expensive it was to go back and forth between Europe and the United States … I had to get on an airplane to see the people I love”) and – a crucial criterion for a foodie book – could actually imagine making most of these recipes, everything from plum preserves and a Swiss chard and Gruyère bake to a towering gooseberry meringue cream cake.

Other readalikes: From Scratch: A Memoir of Love, Sicily, and Finding Home by Tembi Locke, My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, and Only in Naples: Lessons in Food and Famiglia from My Italian Mother-in-Law by Katherine Wilson

Source: A birthday gift from my wish list last year

My rating:

The Not the Wellcome Prize Blog Tour: Francesca Segal and Ian Williams

It’s my stop on the “Not the Wellcome Prize” blog tour. With two dozen reviews of health-themed 2019 books to choose from, I decided to nominate these two for the longlist because they’re under the radar compared to some other medical releases, plus they showcase the breadth of the books that the Prize recognizes: from a heartfelt memoir of a mother welcoming premature babies to a laugh-out-loud graphic novel about a doctor practicing in a small town in Wales. (The Prize website says “picture-led books are not eligible,” so in fact it is likely that graphic novels have never been considered, but we’ve been flexible with the rules for this unofficial blog tour.)

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal

This first work of nonfiction from the author of the exquisite The Innocents is a visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her twin daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU, “an extremely well-funded prison or perhaps more accurately a high-tech zoo.” In Mother Ship, she strives to come to terms with this unnatural start to motherhood. “Taking my unready daughters from within me felt not like a birth but an evisceration,” she writes. “My children do not appear to require mothering. Instead they need sophisticated medical intervention.”

This first work of nonfiction from the author of the exquisite The Innocents is a visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her twin daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU, “an extremely well-funded prison or perhaps more accurately a high-tech zoo.” In Mother Ship, she strives to come to terms with this unnatural start to motherhood. “Taking my unready daughters from within me felt not like a birth but an evisceration,” she writes. “My children do not appear to require mothering. Instead they need sophisticated medical intervention.”

Segal describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn: between the second novel she’d been in the middle of writing and the all-consuming nature of early parenthood; and between her two girls (known for much of the book as “A-lette” and “B-lette”), who are at one point separated in different hospitals. Her attitude towards the NHS is pure gratitude.

As well as portraying her own state of mind, she crafts twinkly pen portraits of the others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums, who met in a “milking shed” where they pumped breast milk for the babies they were so afraid of losing that they resisted naming. (Though it was touch and go for a while, A-lette and B-lette finally earned the names Raffaella and Celeste and came home safely.) Female friendship is thus a subsidiary theme in this exploration of desperate love and helplessness.

The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams

This sequel to 2014’s The Bad Doctor returns to a medical practice in small-town Wales. This time, though, the focus is on Iwan James’s colleague, Dr. Lois Pritchard, who also puts in two days a week treating embarrassing ailments at the local hospital’s genitourinary medicine clinic. At nearly 40, Lois is a divorcee with no children; just a dog. She enjoys her nights out drinking with her best friend, Geeta, but her carefree life is soon beset by various complications: she has to decide whether she wants to join the health centre as a full partner, a tryst with her new fella goes horribly wrong, and her estranged mother suddenly reappears in her life, hoping that Lois will give her a liver transplant. And that’s not to mention all the drug addicts and VD-ridden lotharios hanging about.

This sequel to 2014’s The Bad Doctor returns to a medical practice in small-town Wales. This time, though, the focus is on Iwan James’s colleague, Dr. Lois Pritchard, who also puts in two days a week treating embarrassing ailments at the local hospital’s genitourinary medicine clinic. At nearly 40, Lois is a divorcee with no children; just a dog. She enjoys her nights out drinking with her best friend, Geeta, but her carefree life is soon beset by various complications: she has to decide whether she wants to join the health centre as a full partner, a tryst with her new fella goes horribly wrong, and her estranged mother suddenly reappears in her life, hoping that Lois will give her a liver transplant. And that’s not to mention all the drug addicts and VD-ridden lotharios hanging about.

Williams was a GP in North Wales for 20 years, and no doubt his experiences have inspired his comics. His tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also touching moments where Lois learns that a doctor is never completely off duty and has no idea what medical or personal challenge will crop up next. The drawing style reminded me most of Alison Bechdel’s or Posy Simmonds’, with single shades from rose to olive alternating as the background. I especially loved the pages where each panel depicts a different patient to show the range of people and complaints a doctor might see in a day. Myriad Editions have a whole “Graphic Medicine” series that I’m keen to explore.

Williams was a GP in North Wales for 20 years, and no doubt his experiences have inspired his comics. His tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also touching moments where Lois learns that a doctor is never completely off duty and has no idea what medical or personal challenge will crop up next. The drawing style reminded me most of Alison Bechdel’s or Posy Simmonds’, with single shades from rose to olive alternating as the background. I especially loved the pages where each panel depicts a different patient to show the range of people and complaints a doctor might see in a day. Myriad Editions have a whole “Graphic Medicine” series that I’m keen to explore.

See below for details of the blogs where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

The shadow panel will choose a shortlist of six titles to be announced on 4 May. We will then vote to choose a winner, with the results of a Twitter poll serving as one additional vote. The Not the Wellcome Prize winner will be announced on 11 May.

Three Review Books: Brian Kimberling, Jessica Pan & Francesca Segal

Three May–June releases: A fish-out-of-water comic novel about teaching English in Prague; and memoirs about acting like an extrovert and giving birth to premature twins.

Goulash by Brian Kimberling

“Look where we are. East meets West. Communism meets capitalism.” In 1998 Elliott Black leaves Indiana behind for a couple of years to teach English in Prague. The opening sequence, in which he discovers that his stolen shoes have been incorporated into an art installation, is an appropriate introduction to a country where bizarre things happen. Elliott doesn’t work for a traditional language school; his students are more likely to be people he meets in the pub or tobacco company executives. Their quirky, deadpan conversations are the highlight of the book.

“Look where we are. East meets West. Communism meets capitalism.” In 1998 Elliott Black leaves Indiana behind for a couple of years to teach English in Prague. The opening sequence, in which he discovers that his stolen shoes have been incorporated into an art installation, is an appropriate introduction to a country where bizarre things happen. Elliott doesn’t work for a traditional language school; his students are more likely to be people he meets in the pub or tobacco company executives. Their quirky, deadpan conversations are the highlight of the book.

Elliott starts dating a fellow teacher from England, Amanda (she “looked like azaleas in May and she spoke like the BBC World Service”), who also works as a translator. They live together in an apartment they call Graceland. Much of this short novel is about their low-key, slightly odd adventures, together and separately, while the epilogue sees Elliott looking back at their relationship from many years later.

I was tickled by a number of the turns of phrase, but didn’t feel particularly engaged with the plot, which was inspired by Kimberling’s own experiences living in Prague.

With thanks to Tinder Press for a proof copy to review.

Favorite passages:

“Sorrowful stories like airborne diseases made their way through the windows and under the doorframe, bubbled up like the bathtub drain. It was possible to fill Graceland with light and color and music and the smell of good food, and yet the flat was like a patient with some untreatable condition, and we got tired of palliative care.”

“‘It’s good to be out of Prague,’ he said. ‘Every inch drenched in blood and steeped in alchemy, with a whiff of Soviet body odor.’ ‘You should write for Lonely Planet,’ I said.”

Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come: An Introvert’s Year of Living Dangerously by Jessica Pan

Like Jessica Pan, I’m a shy introvert (a “shintrovert”) as well as an American in the UK, so I was intrigued to see the strategies she employed and the experiences she sought out during a year of behaving like an extrovert. She forced herself to talk to strangers on the tube, give a talk at London’s Union Chapel as part of the Moth, use friendship apps to make new girlfriends, do stand-up comedy and improv, go to networking events, take a holiday to an unknown destination, eat magic mushrooms, and host a big Thanksgiving shindig.

Like Jessica Pan, I’m a shy introvert (a “shintrovert”) as well as an American in the UK, so I was intrigued to see the strategies she employed and the experiences she sought out during a year of behaving like an extrovert. She forced herself to talk to strangers on the tube, give a talk at London’s Union Chapel as part of the Moth, use friendship apps to make new girlfriends, do stand-up comedy and improv, go to networking events, take a holiday to an unknown destination, eat magic mushrooms, and host a big Thanksgiving shindig.

Like Help Me!, which is a fairly similar year challenge book, it’s funny, conversational and compulsive reading that was perfect for me to be picking up and reading in chunks while I was traveling. Although I don’t think I’d copy any of Pan’s experiments – there’s definitely a cathartic element to reading this; if you’re also an introvert, you’ll feel nothing but relief that she’s done these things so you don’t have to – I can at least emulate her in initiating deeper conversations with friends and pushing myself to attend literary and networking events instead of just staying at home.

With thanks to Doubleday UK for a proof copy to review.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal

I’m a big fan of Segal’s novels, especially The Innocents, one of the loveliest debut novels of the last decade, so I was delighted to hear she was coming out with a health-themed memoir about giving birth to premature twins. Mother Ship is a visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU, “an extremely well-funded prison or perhaps more accurately a high-tech zoo.”

Segal strives to come to terms with this unnatural start to motherhood. “Taking my unready daughters from within me felt not like a birth but an evisceration,” she writes; “my children do not appear to require mothering. Instead they need sophisticated medical intervention.” She describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn: between the second novel she’d been in the middle of writing and the all-consuming nature of early parenthood; and between her two girls (known for much of the book as “A-lette” and “B-lette”), who are at one point separated in different hospitals.

Spotted at Philadelphia airport.

As well as portraying her own state of mind, Segal crafts twinkly pen portraits of the others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums, who met in a “milking shed” where they pumped breast milk for the babies they were so afraid of losing that they resisted naming. (Though it was touch and go for a while, A-lette and B-lette finally earned the names Raffaella and Celeste and came home safely.) Female friendship is a subsidiary theme in this exploration of desperate love and helplessness. The layman’s look at the inside workings of medicine would have made this one of my current few favorites for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize (which, alas, is on hiatus). After encountering some unpleasant negativity about the NHS in a recent read, I was relieved to find that Segal’s outlook is pure gratitude.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Margaret Atwood Reading Month: Surfacing and The Edible Woman

For the Margaret Atwood Reading Month hosted by Marcie and Naomi, I read her first two novels – though I didn’t realize they were so at the time, and read them in reverse order. These were my 18th and 19th Atwood books overall, and my 11th and 12th of her novels. It was particularly interesting to see the germ of her frequent themes in these early works.

Surfacing (1972)

(At 186 pages, this just about fit into Novellas for November too!) A young Canadian woman has returned to her French-speaking hometown, ostensibly to search for her missing father but really to search for herself. She’s an illustrator at work on a collection of Quebec folk tales, and in her past are a husband and child that she left behind. With her at her father’s lakeside cabin are her boyfriend Joe, whom she’s not sure she loves, and their friends David and Anna, a married couple whose dynamic is rather disturbing – David is always making demeaning sexualized jokes about Anna, who is afraid for him to see her without makeup on.

This is a drifting, dreamy sort of book whose gorgeous nature writing (“Above the trees streaky mackerel clouds are spreading in over the sky, paint on a wet page; no wind at lake level, soft feel of the air before rain”) inures you to various threats. You’re never sure just how serious they’ll turn out to be. Will the men’s attitude to women spill over into outright assault? Will there be some big blowup with the resented Americans who are monopolizing the lake? (“We used to think they were harmless and funny and inept and faintly lovable, like President Eisenhower.”)

This is a drifting, dreamy sort of book whose gorgeous nature writing (“Above the trees streaky mackerel clouds are spreading in over the sky, paint on a wet page; no wind at lake level, soft feel of the air before rain”) inures you to various threats. You’re never sure just how serious they’ll turn out to be. Will the men’s attitude to women spill over into outright assault? Will there be some big blowup with the resented Americans who are monopolizing the lake? (“We used to think they were harmless and funny and inept and faintly lovable, like President Eisenhower.”)

Meanwhile, the question of her father’s whereabouts becomes less and less important as the book goes on. The narrator seems to have closed herself off to emotion, but all that’s repressed returns dramatically in the final 20 pages (“From any rational point of view I am absurd; but there are no longer any rational points of view.”).

I suspect there may be a fair bit I missed; the book would probably benefit from future re-readings and even some exploration of secondary sources to think about all that’s going on. It’s maybe not as accessible and plot-heavy as much of Atwood’s later work, but I found it to be an intriguing and rewarding read, and it still feels timely more than four decades later.

The Edible Woman (1969)

Marian McAlpin works for Seymour Surveys, administering questionnaires about rice pudding and a new brand of beer. She shares an apartment with Ainsley, who tests electric toothbrushes, in the home of a harridan of a landlady who monitors their every move. Marian is happy enough with her boyfriend Peter and gradually drifts into an engagement – but she can’t stop thinking about Duncan, an apathetic graduate student whom she met during her survey rounds and ran into again at the laundromat. Duncan represents a sort of strings-free relationship that contrasts with the traditional marriage she’d have with Peter. Her challenge is to overcome the inertia of convention and decide what she really wants from her life.

Part Two’s shift from first person to third person is a signal that Marian is dissociating from her situation. She recoils from food and pregnancy – two facts of bodily life that the book’s characters embrace greedily or turn from in horror. Gradually Marian eliminates more and more foods from her diet, starting with meat. And while Ainsley concocts a devious plan to get pregnant by Marian’s friend Len, Marian keeps in mind the cautionary tale of her college friend Clara, whose three monstrous children are always peeing on people or going off to poop in corners. Marian perceives Clara as having given up her mind in favor of her womb.

Part Two’s shift from first person to third person is a signal that Marian is dissociating from her situation. She recoils from food and pregnancy – two facts of bodily life that the book’s characters embrace greedily or turn from in horror. Gradually Marian eliminates more and more foods from her diet, starting with meat. And while Ainsley concocts a devious plan to get pregnant by Marian’s friend Len, Marian keeps in mind the cautionary tale of her college friend Clara, whose three monstrous children are always peeing on people or going off to poop in corners. Marian perceives Clara as having given up her mind in favor of her womb.

It’s unclear whether we’re meant to see Marian’s experience as a temporary eating disorder or a physical manifestation of endangered femininity. Now that veganism is mainstream, it sounds dated to hear her lamenting, “I’m turning into a vegetarian, one of those cranks; I’ll have to start eating lunch at Health Bars.” In any case, you can spot themes that will recur in Atwood’s later work, like the threat of the male gaze (Surfacing), the perception of the female body (Lady Oracle), manipulation of pregnancy (The Handmaid’s Tale) and so on. I can’t say I particularly enjoyed this novel, but I liked the food metaphors and laughed at the over-the-top language about babies.

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.  An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

This short, intense novel is about two women locked into resentful competition. Tara and Antara also happen to be mother and daughter. When the long-divorced Tara shows signs of dementia, artist Antara and her American-born husband Dilip take her into their home in Pune, India. Her mother’s criticism and strange behavior stir up flashbacks to the 1980s and 1990s, when Antara felt abandoned by Tara during the four years they lived in an ashram and then her time at boarding school. Emotional turmoil led to medical manifestations like excretory issues and an eating disorder, and both women fell in love in turn with a homeless photographer named Reza Pine.

This short, intense novel is about two women locked into resentful competition. Tara and Antara also happen to be mother and daughter. When the long-divorced Tara shows signs of dementia, artist Antara and her American-born husband Dilip take her into their home in Pune, India. Her mother’s criticism and strange behavior stir up flashbacks to the 1980s and 1990s, when Antara felt abandoned by Tara during the four years they lived in an ashram and then her time at boarding school. Emotional turmoil led to medical manifestations like excretory issues and an eating disorder, and both women fell in love in turn with a homeless photographer named Reza Pine. Reminiscent of the work of David Grossman, this is the story of two fathers, one Israeli and one Palestinian, who lost their daughters to the ongoing conflict between their nations: Rami Elhanan’s 13-year-old daughter Smadar was killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber, while Bassam Aramin’s 10-year-old daughter Abir was shot by Israeli border police. The two men become unlikely friends through their work with a peacemaking organization, with Bassam also expanding his sense of compassion through his studies of the Holocaust.

Reminiscent of the work of David Grossman, this is the story of two fathers, one Israeli and one Palestinian, who lost their daughters to the ongoing conflict between their nations: Rami Elhanan’s 13-year-old daughter Smadar was killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber, while Bassam Aramin’s 10-year-old daughter Abir was shot by Israeli border police. The two men become unlikely friends through their work with a peacemaking organization, with Bassam also expanding his sense of compassion through his studies of the Holocaust. The New Wilderness by Diane Cook: The blurb promised an interesting mother–daughter relationship, but so far this is dystopia by numbers. A wilderness living experiment started with 20 volunteers, but illnesses and accidents have reduced their number. Bea was an interior decorator and her partner, Glen, a professor of anthropology – their packing list and habits echo primitive human culture. I loved the rituals around a porcelain teacup, but in general the plot and characters weren’t promising. I read Part I (47 pages) and would only resume if this makes the shortlist, which seems unlikely. (See this extraordinarily detailed 1-star

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook: The blurb promised an interesting mother–daughter relationship, but so far this is dystopia by numbers. A wilderness living experiment started with 20 volunteers, but illnesses and accidents have reduced their number. Bea was an interior decorator and her partner, Glen, a professor of anthropology – their packing list and habits echo primitive human culture. I loved the rituals around a porcelain teacup, but in general the plot and characters weren’t promising. I read Part I (47 pages) and would only resume if this makes the shortlist, which seems unlikely. (See this extraordinarily detailed 1-star  Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart: Dialect + depressing subject matter = a hard slog. Poverty and alcoholism make life in 1980s Glasgow a grim prospect for Agnes Bain and her three children. So far, the novel is sticking with the parents and the older children, with the title character barely getting a mention. I did love the scene where Catherine goes to Leek’s den in the pallet factory. This is a lot like the account Damian Barr gives of his childhood in

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart: Dialect + depressing subject matter = a hard slog. Poverty and alcoholism make life in 1980s Glasgow a grim prospect for Agnes Bain and her three children. So far, the novel is sticking with the parents and the older children, with the title character barely getting a mention. I did love the scene where Catherine goes to Leek’s den in the pallet factory. This is a lot like the account Damian Barr gives of his childhood in  Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s

Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s  These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of

These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of  Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder.

Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder. Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires.

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires. With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life.

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life. Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps.

Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps. The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity. The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype.

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype. An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters.

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters. The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market. The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word.

The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word. Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing.

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing. Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us.

Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us. Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones.

Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones. Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children. Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth.

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth. Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations.

Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations. The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits.

The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits.