20 Books of Summer, 13–16: Tony Chan, Jen Hadfield, Kenward Anthology, Catherine Taylor

Three from my initial list (all nonfiction) and one substitute picked up at random (poetry). These are strongly place-based selections, ranging from Sheffield to Shetland and drawing on travels while also commenting on how gender and dis/ability affect daily life as well as the experience of nature.

Four Points Fourteen Lines by Tony Chan (2016)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library) ![]()

Storm Pegs: A Life Made in Shetland by Jen Hadfield (2024)

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place.

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free paperback copy for review.

From Shetland authors, I have also reviewed:

Orchid Summer by Jon Dunn (Hadfield mentions him)

Sea Bean by Sally Huband (Hadfield meets her)

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, ed. Louise Kenward (2023)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list) ![]()

The Stirrings: Coming of Age in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor (2023)

“A typical family and an ordinary story, although neither the family nor the story seems commonplace when it is your family and your story.”

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token)

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token) ![]()

October Books: Ballard, Czarnecki, Moss, Oliver, Ostriker, Steed & More

Apparently October is THE biggest month of the year for new releases. A sterling set came my way this year, including two beautiful novella-length memoirs, a luxuriantly illustrated work dedicated to an everyday bird species, two very different but equally elegant poetry collections, and a book of offbeat comics. Time and concentration only allow for a paragraph or so on each, but I hope that gives a flavour of the contents and will pique interest in the ones that suit you best. Plus I excerpt and link to my BookBrowse review of a poignant story of sisters and mental illness, and my Shelf Awareness review of a fantastic graphic novel adaptation.

Bound: A Memoir of Making and Remaking by Maddie Ballard

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

I lower the needle and the world recedes. The process of sewing a garment – printing the pattern, tracing and cutting, sewing the first and the second and the fiftieth seam – is a lesson in taking your time.

Like gardening, sewing is an investment in the future – in what sort of person your future self will be, and how she will feel about her body, and what she will want to wear.

Similar to two other very short works of nonfiction I’ve read from The Emma Press, How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart by Florentyna Leow and Tiny Moons by Nina Mingya Powles (Ballard, too, is from New Zealand), this is a graceful, enriching book about a young woman making her way in the world and figuring out what is essential to her sense of home and identity. I commend it whether or not you have any particular interest in handicraft.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Encounters with Inscriptions: A Memoir Exploring Books Gifted by Parents by Kristin Czarnecki

When Kristin Czarnecki got in touch to offer a copy of her bibliomemoir about revisiting the books her late parents gifted her, I was instantly intrigued but couldn’t have known in advance how perfect it would be for me. Niche it might seem, but it combines several of my reading interests: bereavement, books about books, relationships with parents (especially a mother) and literary travels.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

It seems fitting to be reviewing this on the second anniversary of my mother’s death. The afterword, which follows on from the philosophical encouragement of a chapter on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, exhorts readers to cherish loved ones while we can – and be grateful for the tokens they leave behind. I had told Kristin about books my parents inscribed to me, as well as the journals I inherited from my mother. But I didn’t know there would be other specific connections between us, too, such as being childfree and hopeless in the kitchen. (Also, I have family in South Bend, Indiana, where she’s from, and our mothers were born in the first week of August.) All that to say, I felt that I found a kindred spirit in this lovely book, which is one of the nicest things that happens through reading.

With thanks to the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Starling: A Biography by Stephen Moss

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Overall, the style of the book is dry and slightly workmanlike. However, when he’s recounting murmurations he’s seen in Somerset or read about, Moss’s enthusiasm lifts it into something special. Autumn dusk is a great time to start watching out for starling gatherings. I love observing and listening to the starlings just in the treetops and aerials of my neighbourhood, but we do also have a small local murmuration that I try to catch at least a few times in the season. Here’s how he describes their magic: “At a time when, both as a society and as individuals, we are less and less in touch with the natural world, attending this fleeting but memorable event is a way we can reconnect, regain our primal sense of wonder – and still be home in time for tea.”

With thanks to Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage (Penguin Random House) for the free copy for review.

The Alcestis Machine by Carolyn Oliver

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

The Holy & Broken Bliss: Poems in Plague Time by Alicia Ostriker

“The words of an old woman shuffling the cards of her own decline the decline

of her husband the decline of her nation her plague-smitten world”

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

It is almost winter and still

as I walk to the clinic the gingkos

sing their seraphic air

as if there is no tomorrow

With thanks to Alice James Books for the advanced e-copy for review.

Forces of Nature by Edward Steed

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

With thanks to Drawn & Quarterly for the e-copy for review.

Reviewed for BookBrowse:

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

Book Serendipity, June to Mid-August 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A self-induced abortion scene in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

- A woman who cleans buildings after hours, and a character named Tova who lives in the Seattle area in A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Flirting with a surf shop employee in Sandwich by Catherine Newman and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Living in Paris and keeping ticket stubs from all films seen in Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer and The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick.

- A schefflera (umbrella tree) is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Company by Shannon Sanders.

- The Plague by Albert Camus is mentioned in Knife by Salman Rushdie and Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- Making egg salad sandwiches is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Sandwich by Catherine Newman.

- Pet rats in Stowaway by Joe Shute and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman. Rats are also mentioned in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Eels feature in Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma, Late Light by Michael Malay, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Atlantic City, New Jersey is a location in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Company by Shannon Sanders.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

- A New Zealand setting (but very different time periods) in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- A mention of Melanie Griffith’s role in Working Girl in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- A poet with a collection that was published on 6 August mentions a constant ringing in the ears: Joshua Jennifer Espinoza (I Don’t Want to Be Understood) and Keith Taylor (What Can the Matter Be?).

- A discussion of the original meaning of “slut” (a slovenly housekeeper) vs. its current sexualized meaning in Girlhood by Melissa Febos and Sandi Toksvig’s introduction to the story anthology Furies.

- An odalisque (a concubine in a harem, often depicted in art) is mentioned in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley.

- Reading my second historical novel of the year in which there’s a disintegrating beached whale in the background of the story: first was Whale Fall by Elizabeth O’Connor, then Come to the Window by Howard Norman.

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

- Her partner, a lawyer, is working long hours and often missing dinner, leading the protagonist to assume that he’s having an affair with a female colleague, in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- A fierce boss named Jo(h)anna in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- An OTT rendering of a Scottish accent in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A Padstow setting and a mention of Puffin Island (Cornwall) in The Cove by Beth Lynch and England as You Like It by Susan Allen Toth.

- A mention of the Big and Little Dipper (U.S. names for constellations) in Directions to Myself by Heidi Julavits and How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica.

- A mention of Binghamton, New York and its university in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- A character accidentally drinks a soapy liquid in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and one story of The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- The ex-husband’s name is Jonah in The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- The husband’s name is John in Dot in the Universe by Lucy Ellmann and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- An affair is discovered through restaurant receipts in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of eating fermented shark in The Museum of Whales You Will Never See by A. Kendra Greene and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of using one’s own urine as a remedy in Thunderstone by Nancy Campbell and Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa.

- The main character tries to get pregnant by a man even though one of the partners is gay in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Until the Real Thing Comes Along by Elizabeth Berg.

- Motherhood is for women what war is for men: this analogy is presented in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case, Parade by Rachel Cusk, and Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A woman bakes bread for the first time in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans.

- A gay couple adopts a Latino boy in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and one story of There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A man is haunted by things his father said to him years ago in Parade by Rachel Cusk and one story in There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- Two short story collections in a row in which a character is a puppet (thank you, magic realism!): The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer, followed by There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- A farm is described as having woodworm in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Parade by Rachel Cusk.

- Sebastian as a proposed or actual name for a baby in Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus and Birdeye by Judith Heneghan.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Winter Reads: Claire Tomalin, Daniel Woodrell & Picture Books

Mid-February approaches and we’re wondering if the snowdrops and primroses emerging here in the South of England mean that it will be farewell to winter soon, or if the cold weather will return as rumoured. (Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow, but that early-spring prediction is only valid for the USA, right?) I didn’t manage to read many seasonal books this year, but I did pick up several short works with “Winter” in the title: a little-known biographical play from a respected author, a gritty Southern Gothic novella made famous through a Jennifer Lawrence film, and two picture books I picked up at the library last week.

The Winter Wife by Claire Tomalin (1991)

A search of the university library catalogue turned up this Tomalin title I’d never heard of. It turns out to be a very short play (two acts of seven scenes each, but only running to 44 pages in total) about a trip abroad Katherine Mansfield took with her housekeeper?/companion, Ida Baker, in 1920. Ida clucks over Katherine like a nurse or mother hen, but there also seems to be latent, unrequited love there (Mansfield was bisexual, as I knew from fellow New Zealander Sarah Laing’s fab graphic memoir Mansfield and Me). Katherine, for her part, alternately speaks to Ida, whom she nicknames “Jones,” with exasperation and fondness. The title comes from a moment late on when Katherine tells Ida “you’re the perfect friend – more than a friend. You know what you are, you’re what every woman needs: you’re my true wife.” Maybe what we’d call a “work wife” today, but Ida blushes with pride.

Tomalin had already written a full-length biography of Mansfield, but insists she barely referred to it when composing this. The backdrops are minimal: a French sleeper train; Isola Bella, a villa on the French Riviera; and Dr. Bouchage’s office. Mansfield was ill with tuberculosis, and the continental climate was a balm: “The sun gets right into my bones and makes me feel better. All that English damp was killing me. I can’t think why I ever tried to live in England.” There are also financial worries. The Murrys keep just one servant, Marie, a middle-aged French woman who accompanies her on this trip, but Katherine fears they’ll have to let her go if she doesn’t keep earning by her pen.

Through Katherine’s conversations with the doctor, we catch up on her romantic history – a brief first marriage, a miscarriage, and other lovers. Dr. Bouchage believes her infertility is a result of untreated gonorrhea. He echoes Ida in warning Katherine that she’s working too hard – mostly reviewing books for her husband John Middleton Murry’s magazine, but also writing her own short stories – when she should be resting. Katherine retorts, “It is simply none of your business, Jones. Dr Bouchage: if I do not work, I might as well be dead, it’s as simple as that.”

She would die not three years later, a fact that audiences learn through a final flash-forward where Ida, in a monologue, contrasts her own long life (she lived to 90 and Tomalin interviewed her when she was 88) with Katherine’s short one. “I never married. For me, no one ever equalled Katie. There was something golden about her.” Whereas Katherine had mused, “I thought there was going to be so much life then … that it would all be experience I could use. I thought I could live all sorts of different lives, and be unscathed…”

The play is, by its nature, slight, but gives a lovely sense of the subject and her key relationships – I do mean to read more by and about Mansfield. I wonder if it has been performed much since. And how about this for unexpected literary serendipity?

Yes, it’s that Rachel Joyce. (University library)

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

Forced to undertake a frozen odyssey to find traces of Jessup, she’s unwelcome everywhere she goes, even among extended family. No one is above hitting a girl, it seems, and just for asking questions Ree gets beaten half to death. Her only comfort is in her best friend, Gail, who’s recently given birth and married the baby daddy. Gail and Ree have long “practiced” on each other romantically. Without labelling anything, Woodrell sensitively portrays the different value the two girls place on their attachment. His prose is sometimes gorgeous –

Pine trees with low limbs spread over fresh snow made a stronger vault for the spirit than pews and pulpits ever could.

– but can be overblown or off-puttingly folksy:

Ree felt bogged and forlorn, doomed to a spreading swamp of hateful obligations.

Merab followed the beam and led them on a slow wamble across a rankled field

This was my second from Woodrell, after the short stories of The Outlaw Album. I don’t think I’ll need to try any more by him, but this was a solid read. (Secondhand – New Chapter Books, Wigtown)

Children’s picture books:

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,  I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,  I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

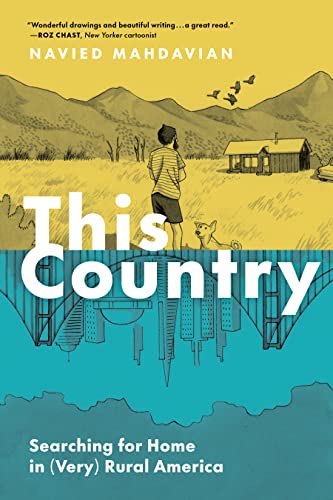

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on. Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs. Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A  This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is. (Already featured in my

(Already featured in my  A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home. The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to  A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations. This was my second Arachne Press collection after

This was my second Arachne Press collection after  A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,

A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,  I was a big fan of Katherine May’s

I was a big fan of Katherine May’s  The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this

The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this  Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my  Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.”

Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.” Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.”

Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.” The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community.

The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community. less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro.

less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro. This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

I approached this as a companion to

I approached this as a companion to  A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.

A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.