Tag Archives: parenthood

December Releases by Anita Felicelli, Lise Goett, Brooke Randel & Weike Wang

December isn’t a big month for new releases, but here are excerpts from a few I happened to review early for U.S. publications BookBrowse, Foreword Reviews, and Shelf Awareness: Speculative short stories, loss-tinged poetry, a family memoir based on Holocaust history, and a satirical short novel about racial microaggressions and class divides in contemporary America.

How We Know Our Time Travelers by Anita Felicelli

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full Foreword review.)

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full Foreword review.)

The Radiant by Lise Goett

In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness)

In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness)

Also Here: Love, Literacy, and the Legacy of the Holocaust by Brooke Randel

Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full Shelf Awareness review.)

Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full Shelf Awareness review.)

Rental House by Weike Wang

Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full BookBrowse review.)

Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full BookBrowse review.)

Three on a Theme: Matrescence Memoirs (and a Bonus Novel)

I think of pregnancy and childbirth like any extreme adventure (skydiving, polar exploration): wholly extraordinary experiences with much to recommend them – though better appreciated retrospectively than in the moment – to which my response is a hearty “no, thanks.” But just as books have taken me to deserts and the frozen north, miles above or below the earth, into many eras and cultures, they’ve long been my window onto motherhood.

Matrescence, a word coined by anthropologist Dana Raphael in the 1970s, is the process of becoming a mother. It’s a transition period, like adolescence, that involves radical physical and mental changes and has lasting effects. And as Lucy Jones reports, up to 45% of women describe childbirth as traumatic. That’s not a niche experience; it’s an epidemic. If it was men going through this, you can bet it would be at the top of international research agendas.

These three memoirs (and a bonus novel) are bold, often harrowing accounts of the metamorphosis involved in motherhood. They’re personal yet political in how they expose the lack of social support for creating and raising the next generation. All four of these 2023 releases are eye-opening, lyrical and vital; they deserve to be better known.

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones

Like Jones’s previous book, Losing Eden, about climate breakdown and the human need for nature, Matrescence is a potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. She has synthesized a huge amount of information into a tight 260-some pages that are structured thematically but also proceed roughly chronologically through her own matrescence. Not long into her pregnancy with her first child, a daughter, she realised the extent to which outdated and sexist expectations still govern motherhood: concepts like “natural childbirth” and “maternal instinct,” the judgemental requirement for exclusive breastfeeding, the idea that a parent should “enjoy every minute” of their offspring’s babyhood rather than admitting depression or overwhelm. After the cataclysm of birth, loneliness set in. “Matrescence was another country, another planet. I didn’t know how to talk about the existential crisis I was facing, or the confronting, encompassing relationship I was now in.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. A purely scientific approach might have been dry; a social history well-trod and worthy; a memoir too inward-looking to make wider points. Instead it’s equally committed to all three purposes. I appreciated the laser focus on her own physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. The literary touches – lists and word clouds, verse-like meditations and flash vignettes about natural phenomena – are not always successful, but there is a thrill to seeing Jones experimenting. Like Leah Hazard’s Womb, this is by no means a book that’s just for mothers; it’s for anyone who’s ever had a mother.

With thanks to Allen Lane (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

Milk: On Motherhood and Madness by Alice Kinsella

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

I liked this most when the author stuck close to her own sensory and emotional life; overall, the book felt too long and I thought a late segue into an argument against the dairy industry was unnecessary. Had I been the editor, I would have cut the titled essays and just stuck to the time-stamped pieces. At its best, though, this is a poetic engagement with the tropes and reality of motherhood, sometimes delivered in paragraphs that more closely resemble verse:

+1 I have become the common myth. Mother. The sleepy hum of early memories. The smell of shampoo, of Olay, of lavender. The feeling of safety. The absence of fear.

+2 There’s a possibility,

that we are among the happiest

people in the world:

mothers.[Record freeze preserve.] Fighting death by reproducing our days. Fighting death by reproducing. Here: your life on paper. Here: their life to come.

We’re expected to be mothers the instant we lock eyes with our baby. To shed everything we were and be reborn: Madonnas.

The baby’s favourite thing to do is sit on my lap and interact with other people. This is what mothers are for, I think. Comfort, security, a place to get to know the world from.

The language is gorgeous, and while Kinsella complains of disorientation to the point of worrying about losing herself (although she had struggled with mental health earlier in life, the subtitle’s reference to ‘madness’ seemed to me like overkill compared to other memoirs I’ve read of postpartum depression, trauma or psychosis, such as Inferno by Catherine Cho and Birth Notes by Jessica Cornwell), she comes across as entirely lucid. Her goal here is to find and add to the missing literature of motherhood, in much the same way that Jazmina Barrera, another young mother and writer, attempted with Linea Nigra. This would also make a good companion read to A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa.

Kinsella is among my predictions for the Sunday Times Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist, along with Eliza Clark (Penance) and Tom Crewe (The New Life). (Public library)

The Unfamiliar: A Queer Motherhood Memoir by Kirsty Logan

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

To start with, Logan’s wife Annie tried getting pregnant. They had a known sperm donor and did home insemination, then advanced to IVF. But after three miscarriages and a failed cycle, they took a doctor’s advice and switched to the younger womb – Logan’s, by four years. As “The Planning” makes way for “The Growing,” it helps that Annie knows exactly what she’s going through. The pregnancy sticks, though the fear of something going wrong never abates, and after the alternating magic and discomfort of those nine months (“You’ve reached the ‘shoplifting a honeydew’ stage”) it’s time for “The Birth,” as horrific an account as I’ve read. The baby had shifted to be back-to-back, which required an emergency C-section, but before that there was a sense of total helplessness, abandonment to unmanaged pain.

Finally the doctor comes. She asks what you would like, and you, shaking shitting pissing bleeding, unable to see when the pain reaches its peak, not screaming, not swearing, not being rude to anyone, not begging for an epidural, … say: I’d like to try some gas and air, if that’s okay, please.

What is remarkable is how Logan recreates this time so intensely – she took notes all through the pregnancy, plus on her phone in hospital and in the early days after bringing the baby home – but can also see how, even in the first hours, she was shaping it into a narrative. “You like that it’s a story. You like that it’s Gothic and gory … and funny.” Except it wasn’t. “You thought you were going to die.” And yet. “How can the lucid, everyday world explain this? The wonder, the curiosity, the recognition. The baby has lived inside your body, and you’ve only just met. The baby is your familiar, and deeply unfamiliar.”

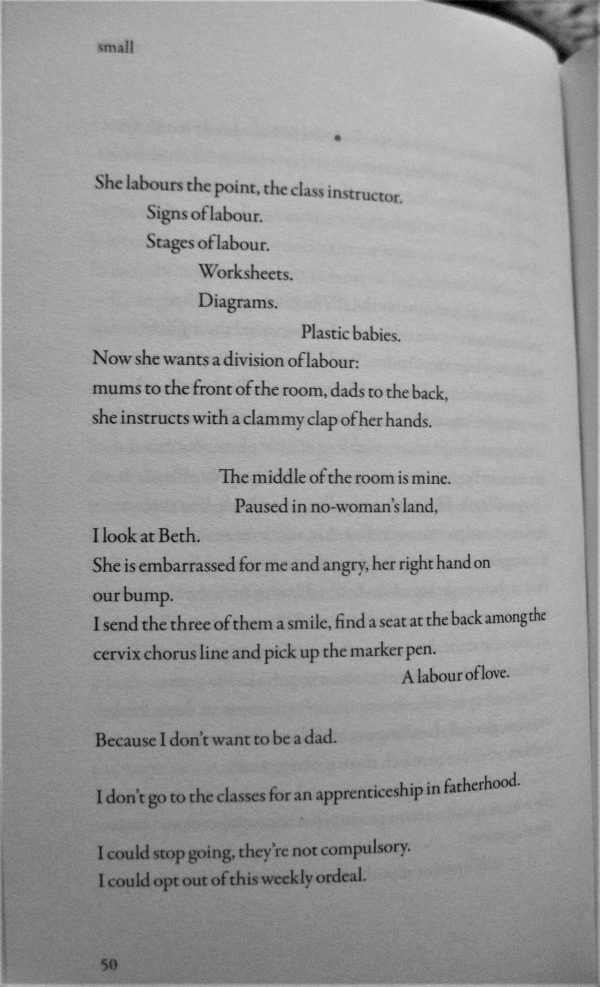

This reminded me of other memoirs I’ve read about queer family-making, especially small by Claire Lynch, which similarly turns on the decision about which female partner will carry the pregnancy and is written in an experimental style. The Unfamiliar is utterly absorbing and conveys so much about the author and her family, even weaving in her father’s death seven years before. I’ve signed up for Logan’s online memoir-writing course (“Where to Start and Where to End”) organised by Writers & Artists (part of Bloomsbury) for next month.

With thanks to Virago Press for the free copy for review.

And, as a bonus, a short novel that deals with many of these same themes:

Reproduction by Louisa Hall

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout, which I read last year. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, moving with Hall from Texas to New York to Montana to Iowa as she marries, takes on various university teaching roles and goes through two miscarriages and then, in the “Birth” section, the traumatic birth of her daughter, after which she required surgery and blood transfusions.

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout, which I read last year. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, moving with Hall from Texas to New York to Montana to Iowa as she marries, takes on various university teaching roles and goes through two miscarriages and then, in the “Birth” section, the traumatic birth of her daughter, after which she required surgery and blood transfusions.

These first two sections are exceptional. There’s a sublime clarity to them, like life has been transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. The change of gears to the third section, “Science Fiction,” put me off, and it took me a long time to get back into the flow. In this final part, the narrator reconnects with a friend and colleague, Anna, who is determined to get pregnant on her own and genetically engineer her embryos to minimise all risk. Here she is more like a Rachel Cusk protagonist, eclipsed by another’s story and serving primarily as a recorder. I found this tedious. It all takes place during Trump’s presidency [Laura F. told me I accidentally published with that saying pregnancy – my brain was definitely saturated with the topic after these reads!] and the Covid pandemic, heightening the strangeness of matrescence and of the lengths Anna goes to. “What, after all, in these end times we lived in, was still really ‘natural’ at all?” the narrator ponders. She casts herself as the narrating Walton, and Anna as Dr. Frankenstein (or sometimes his monster), in this tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. It’s brilliantly envisioned, and – almost – flawlessly executed. (Public library)

Additional related reading:

Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth

After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth

And coming out in 2025: Mother, Animal by Helen Jukes (Elliott & Thompson)

September Releases by Chloe Lane, Ben Lerner, Navied Mahdavian & More

September and October are bounteous months in the publishing world. I’ll have a bunch of books to plug in both, mostly because I’ve upped my reviewing quota for Shelf Awareness. There’s real variety here, from contemporary novellas and heavily autobiographical poetry to nature essays and a graphic memoir.

Arms & Legs by Chloe Lane

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel, The Swimmers, a black comedy about a family preparing for an assisted suicide, this time last year. It seems there’s an autobiographical setup to the author’s follow-up, which focuses on a couple from New Zealand now living in Florida with their young son. Narrator Georgie teaches writing at a local college and is having an affair with Jason, an Alabama-accented librarian she met through taking Finn to the Music & Movement class. She joins in a volunteer-led controlled burn in the forest, and curiosity quickly turns to horror when she discovers the decaying body of a missing student.

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel, The Swimmers, a black comedy about a family preparing for an assisted suicide, this time last year. It seems there’s an autobiographical setup to the author’s follow-up, which focuses on a couple from New Zealand now living in Florida with their young son. Narrator Georgie teaches writing at a local college and is having an affair with Jason, an Alabama-accented librarian she met through taking Finn to the Music & Movement class. She joins in a volunteer-led controlled burn in the forest, and curiosity quickly turns to horror when she discovers the decaying body of a missing student.

There’s a strong physicality to this short novel: fire, bodies and Florida’s dangerous fauna (“To choose to live in a place surrounded by these creatures, these threats, it made me feel like I was living a bold life”). Georgie has to decide whether setting fire to her marriage with Dan is what she really wants. A Barry Hannah short story she reads describes adultery as just a matter of arms and legs, a phrase that’s repeated several times.

Georgie is cynical and detached from her self-destructive choices, coming out with incisive one-liners (“My life isn’t a Muriel Spark novel, there’s no way to flash forward and find out if I make it out of the housefire alive” and “He rested the spade on his shoulder as if he were a Viking taking a drinks break in the middle of a battle”). Lane burrows into instinct and motivation, also giving a glimpse of the challenges of new motherhood. Apart from a wicked dinner party scene, though, the book as a whole was underwhelming: the body holds no mystery, and adultery is an old, old story.

With thanks to Gallic Books for the proof copy for review.

The Lights by Ben Lerner

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

The vocabulary and pronouncements can be a little pretentious. The conversational nature and randomness of the subjects contribute to the same autofiction feel you get from his novels. For instance, he probes parenting styles: his parents’ dilemma between understanding his fears and encouraging him in drama and sport; then his daughters’ playful adoption of his childhood nickname of Benner for him.

A few highlights: the enjambment in “Index of Themes”; the commentary on pandemic strictures and contrast between ancient poetry and modern technology in “The Stone.” I wouldn’t seek out more poetry by Lerner, but this was interesting to try. (Read via Edelweiss)

Sample lines:

“When you die in the patent office / there’s a pun on expiration”

“the goal is to be on both sides of the poem, / shuttling between the you and I. … Form / is always the answer to the riddle it poses”

“It’s raining now / it isn’t, or it’s raining in the near / future perfect when the poem is finished / or continuous, will have been completed”

This Country: Searching for Home in (Very) Rural America by Navied Mahdavian

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

I appreciated the self-deprecating depictions of learning DIY from YouTube videos and feeling like a wimp in comparison to his new friends who hunt and have gun collections – one funny spread has him imagining himself as a baby in a onesie sitting across from a manly neighbor. “I am shedding my city madness,” Mahdavian boasts as they plant an abundant garden and start learning about trees and birds. The references to Persian myth and melodrama are intriguing, though sometimes seem à propos of nothing, as do the asides on science and nature. I preferred when the focus was on the couple’s struggles with infertility and reopening the town movie theater – a flop because people only want John Wayne flicks.

This was enjoyable reading, but the simple black-and-white style is unlikely to draw in readers new to graphic storytelling, and I wondered if the overall premise – ‘we expected to find closed-minded racists and we did’ – was enough to hang a memoir on. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

(Links to full text)

The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A here.)

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A here.)

When My Ghost Sings by Tara Sidhoo Fraser

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff

(Already featured in my Best of 2023 so far post.) Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel.

(Already featured in my Best of 2023 so far post.) Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel.

Zoo World: Essays by Mary Quade

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

The Goodbye World Poem by Brian Turner

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to The Wild Delight of Wild Things) dwell in the aftermath of the loss of his wife and others, and cultivate compensatory appreciation for the natural world. Turner’s poetry is gilded with alliteration and maritime metaphors The long title piece, which closes the collection, repeats many phrases from earlier poems—a pleasing way of drawing the book’s themes together. (My review of the third volume in this loose trilogy is forthcoming.)

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to The Wild Delight of Wild Things) dwell in the aftermath of the loss of his wife and others, and cultivate compensatory appreciation for the natural world. Turner’s poetry is gilded with alliteration and maritime metaphors The long title piece, which closes the collection, repeats many phrases from earlier poems—a pleasing way of drawing the book’s themes together. (My review of the third volume in this loose trilogy is forthcoming.)

And a bonus review book, relevant for its title:

September and the Night by Maica Rafecas

[Translated from the Catalan by Megan Berkobien and María Cristina Hall]

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

Certain chapters alternate Jan’s and Anaïs’s perspectives, recreate her confusion in a psychiatric hospital, or have every sentence beginning with “There” or “And” – effective anaphora. Although I didn’t think Jan’s several romantic options added to the plot, this debut novella from a Spanish author was a pleasant surprise. It’s based on a true story, though takes place in fictional locations, and bears a gentle message of cultural preservation.

With thanks to Fum d’Estampa Press for the free copy for review.

May Poetry Releases: Blood & Cord Anthology; Connolly, Goss, Harrison

Apart from Monsters, my focus for May releases has been on poetry, with three Carcanet collections plus a poetry-heavy anthology of writing on early parenthood. Love, history, nature and parental bonds are a few underlying subjects that connect some or all of these.

The Recycling by Joey Connolly

Joey Connolly’s second collection reminded me most of Caroline Bird’s work (especially the mise en abyme ending to “For Such a Widely Used Material, Glass Sure Does Have Some Downsides”): effusive and sometimes absurdist, with unexpected imagery and wordplay.

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

It’s such a versatile book. I loved the philosophical self-questioning of “Why Try and Be Good When This World” (“the / mental carapace required to weather the hardness / of indifference insulates you from what it means to be alive”) and the utterly original love poetry (“I will take out the bins, and I will try not to leave the keys / in the door, and I will continue / to love you / to the fullest extent to which I find myself able. Oh love. Checkmate”). Eminently quotable stuff. Here are two of my favourite passages:

like an

amateur kintsugi enthusiast in the ruined chinashop

of my childhood idealism

What sweet sorrow

to persist within this disappeared world

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Blood & Cord: Writers on Early Parenthood, edited by Abi Curtis

“The introduction of a new baby rearranges a life, and this requires a new language and a new kind of engagement with the world,” Abi Curtis writes in her introduction. These poems and pieces of flash autofiction or memoir are often visceral, as the title and cover image by Elīna Brasliņa indicate. Elizabeth Hogarth’s “Animal Body” tracks how primal instinct takes over. Second- and third-person narratives distance the speaker from the experience, as in Ruth Charnock’s hybrid “three tarot cards for the new mother.” As I’ve come to expect from The Emma Press, there’s a wide variety of formats, styles and even page layout, with some poems printed in landscape.

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

There are certain words that you dread hearing her say. The first is money. … You dread the way it will become as concrete to her as sky and cat and gate. Mu-nee. Mu-nee.

Not all of these are jubilant birth stories. There are children who are longed for but never arrive. There are also babies who never breathe, or soon die. Alex McRae Dimsdale’s “Bath” is a heartbreaking poem about bidding goodbye to a stillborn son:

It wasn’t the first time that a couple had to leave

the hospital without their newborn.

What could they give us instead?

Here, a small white wooden box –

inside, a packet of wildflower seeds,

your wristband, little

stripy hat. A curlicued certificate

inked with your footprints.

…

what maternal sin did I commit,

deciding who you were

for a whole life that was

already stopped before it started?

“Other Mothers,” a prose essay by poet Rebecca Goss (from whom more below), is about her infant daughter’s death in hospital.

There are a few male contributors, outnumbered five to one by women writers. Poets Liz Berry and Gail McConnell illuminate same-sex motherhood. The two short stories – i.e., those that are clearly fiction rather than memoir by different pronouns – were among the weakest pieces for me: the one piles cruel irony on misery (no real surprise as it’s by an author I’ve had a strong reaction against in the past; the only saving grace was a clever reference to Hemingway’s six-word story about baby shoes); the other is silly and contrived.

I think this was my seventh Emma Press book, and my fourth of their anthologies, of which I’d recommend The Emma Press Anthology of Love. This one was a bit more uneven for me, but I can see it holding appeal for new parents who are of a literary bent.

Published in association with the York Centre for Writing, York St John University. With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Latch by Rebecca Goss

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Even the individual poem titles tell tales: “The Retired Agronomist Drives a Tractor in the Summer Because He Likes the Oily Smell of the Machine” and three with the enticing pattern “Woman Returns to Childhood Home…” Trees and animals provide much of the imagery. A few of my personal favourites were “Rooks,” “Weir,” and “In Song Flight.”

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Kitchen Music by Lesley Harrison

Lesley Harrison is a Scottish poet with a number of pamphlets and collections to her name. Orkney and other remote islands are settings for these atmospheric poems filled with whale song and weather (“the vast dark hung with / ropes of song”), birds and wordplay. Language and folktales inspire the poet, and she engages in word association and creates rebuses built around middle letters rather than first. There are also black-and-white photographs, and whale images by Marina Rees punctuating “C-E-T-A-C-E-A.” My attention threatened to drift away from the sometimes wispy lines and paragraphs, but this would be well worth taking on holiday to read on location.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Nature Book Catch-Up: Sally Huband, Richard Smyth & Anna Vaught

I’m catching up with a few nature- and travel-based 2023 releases that were sent to me for review. I’ve grouped them together because these British authors share some of the same interests and concerns. They celebrate beloved places that become ours through the time we spend in them and the attention we grant; they mourn the loss of biodiversity from rockpools and gardens and seabird cliffs. What kind of diminished world they’re raising their children into is a major worry for all three, and for Huband and Vaught the unease is exacerbated by chronic illness. Wild creatures, and the fellow authors who have hymned them, ease the hurt.

Sea Bean: A beachcomber’s search for a magical charm by Sally Huband

After more than a decade in her adopted home of Shetland, Sally Huband is still a newcomer. A tricky path to motherhood and ensuing chronic illness (the autoimmune disease palindromic rheumatism) limited her mobility and career. Beachcombing is at once her way of belonging to a specific place and feeling part of the wider world – what washes up on a Shetland beach might come from as far away as Atlantic Canada or the Caribbean. Sea glass, lobster pot tags, messages in bottles, driftwood … and a whole lot of plastic, of course. Early on, Huband sets her sights on a sea bean – also known as a drift-seed, from the tropics – which in centuries past was a talisman for ensuring safe childbirth. Possession of one was enough to condemn a 17th-century local woman to death for witchcraft, she learned.

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn, one of my all-time favourite nonfiction books, there is delight at the randomness of what the ocean delivers.

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn, one of my all-time favourite nonfiction books, there is delight at the randomness of what the ocean delivers.

I requested this book because Huband’s was my favourite essay in the Antlers of Water anthology. In it, she deplored the fact that women were still not allowed to participate in the Up Helly Aa fire festival in Lerwick. Good news: that is no longer the case, thanks to campaigning by Huband and others. In a late chapter, she also reports that blackface was recently banned from the festivals, and a Black Lives Matter demonstration drew 2000 people. Change does come, but slowly to a traditional island community. And sometimes it is not the right sort of change, as with an enormous wind farm, resisted vigorously by residents, that will primarily enrich a multinational company instead of serving the local people.

In many ways, this is a book about coming to terms with loss, and Huband presents the facts with sombre determination. Passages about the threats to birds and marine life had me near tears. But she writes with such poetic tenderness that the evocative specifics of island life point towards what’s true for all of us making the best of our constraints. I was lucky enough to visit several islands of Shetland in 2006; whether you have or not, this is a radiant memoir I would recommend to readers of Kathleen Jamie, Jean Sprackland and Malachy Tallack.

Some favourite lines:

No island can ever live up to the heightened expectations that we always seem to place on them; life catches up with us, sooner or later.

With each loss, emotional pain accretes for those who have paid attention.

If hope is a hierarchy of wishes then I am happy enough, each time that I beachcomb, to find fragments of the bark of paper birch

I’ve come to think of the ocean as an archive of sorts.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell: Finding Wild Things with My Kids by Richard Smyth

all around us

the stuff of spells. Our parents

let us go to scamper deeper,

leap from stumps lush with moss.

Everything aloof about me

fell into the soil once charged

with younger siblings

and freedoms of a wood.

…

I give you a damp valley floor,

this feather for your pocket.

~an extract from “Arger Fen,” from Latch by Rebecca Goss

I know Richard Smyth for his writing on birds (I’ve reviewed both A Sweet, Wild Note and An Indifference of Birds) and his somewhat controversial commentary on modern nature writing. This represents a change in direction for him toward more personal reflection, and with its focus on the phenomena of childhood and parenthood it recalls Wild Child by Patrick Barkham and The Nature Seed by Lucy Jones and Kenneth Greenway. But, as I knew to expect from previous works, he has such talent for reeling in the tangential and extrapolating from the concrete to the abstract that this lively read ends up being about everything: what it is to be human on this fading planet.

And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?

And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?

It’s still, unfortunately, rare for men to write about parenthood (and especially pregnancy loss – I only think of Native by Patrick Laurie and William Henry Searle’s books), so it’s great to see that represented, and it’s a charming idea that we create “downfamily” because the “upfamily” doesn’t last forever. Although there’s nostalgia for his childhood here, and anxiety about his kids’ chances of seeing wildlife in abundance, Smyth doesn’t get mired in the past or in existential dread. He has a humanist belief that people are essentially good and can do positive things like build offshore wind farms, and in the meantime he will take Genevieve and Daniel into the woods to play so they will develop a sense of wonder at all that lives on. Even for someone like me who doesn’t have children, this was a captivating, thought-provoking read: We’re all invested in the future of life on this planet.

With thanks to Icon Press for the free copy for review.

These Envoys of Beauty: A Memoir by Anna Vaught

Anna Vaught is a versatile author: I have a copy of her mental health-themed novel Saving Lucia, longlisted for the inaugural Barbellion Prize, on the shelf; she’s written a spooky set of stories, Famished (see Susan’s review); and I gave some early reader feedback on the opening pages of her forthcoming work of quirky historical fiction, The Zebra and Lord Jones. She’s also publishing a book on writing, and editing a collection of pieces submitted for the first Curae Prize for writers who are also carers. I was drawn to her first nonfiction release by reviews by fellow bloggers – it’s always good when a blog tour achieves its aim!

These dozen short essays are about how nature doesn’t necessarily heal, but is a most valued companion in a life marked by chronic illness and depression. The evocative title and epigraphs are from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature” (1836). The pieces loop through Vaught’s past and present, focussing on favourite places in Wiltshire, where she lives, and at the Pembrokeshire coast. It’s the second memoir about complex PTSD that I’ve read this year (see also What My Bones Know). Both at the time and now, when flashbacks of her parents’ verbal and physical abuse haunt her, lying down in a grassy field, exploring a sea cave or sucking on a gorse flower could be a salve. “Nature offered stability and satisfying detail; pattern, form and things that made sense.”

Vaught has a particular love for trees, flowers and moss – even just reciting their Latin names gives her a thrill, and she adds additional information about some species in footnotes. Although her childhood was painful, she retains gratitude for its wide-eyed wonder, and in the exuberance of her prose you can sense a willed childlike perspective (“But back to the list of clouds and writing about clouds!”). I found the frequent self-referential nature of the essays and direct reader address a little precious, but appreciated the thoughts about how nature holds us: “I have always felt a generosity around me, and that I was less lonely outside; at the very least, I could find something to comfort me”. She’s a bookish kindred spirit as well. I’ll be sure to try her work in other genres.

With thanks to Reflex Press for the free copy for review.

R.I.P. Reads, Part I: Ahlberg, Gaskell, Hinchcliffe and Watson

I don’t generally read horror or suspense, but the R.I.P. challenge is my annual excuse to pick up some slightly scarier material. For this first installment of super-short responses, I have a children’s book about a seriously problematic cat, a Victorian ghost story, and two recent Scotland-set novels about exiles haunted by the unexplained. (All: Public library)

The Improbable Cat by Allan Ahlberg (2003)

I picked this up expecting a cute cat tale for children, only realizing afterwards that it’s considered horror. When a grey kitten wanders into their garden, Davy is less enamoured than the rest of the Burrell family. His suspicion mounts as the creature starts holding court in the lounge, expecting lavish meals and attention at all times. His parents and sister seem to be under the cat’s spell in some way, and it’s growing much faster than any young animal should. Davy and his pal George decide to do something about it. Since I’m a cat owner, I’m not big into evil cat stories (e.g., Cat out of Hell by Lynne Truss), and this one was so short as to feel underdeveloped.

I picked this up expecting a cute cat tale for children, only realizing afterwards that it’s considered horror. When a grey kitten wanders into their garden, Davy is less enamoured than the rest of the Burrell family. His suspicion mounts as the creature starts holding court in the lounge, expecting lavish meals and attention at all times. His parents and sister seem to be under the cat’s spell in some way, and it’s growing much faster than any young animal should. Davy and his pal George decide to do something about it. Since I’m a cat owner, I’m not big into evil cat stories (e.g., Cat out of Hell by Lynne Truss), and this one was so short as to feel underdeveloped.

“The Old Nurse’s Story” by Elizabeth Gaskell (1852)

“The Old Nurse’s Story” by Elizabeth Gaskell (1852)

(collected in Gothic Tales (2000), ed. Laura Kranzler)

I had no idea that Gaskell had published short fiction, let alone ghost stories. Based on the Goodreads and blogger reviews, I chose one story to read. The title character tells her young charges about when their mother was a child and the ghost of a little girl tried to lure her out onto the Northumberland Fells one freezing winter. It’s predictable for anyone who reads ghost stories, but had a bit of an untamed Wuthering Heights feel to it.

Hare House by Sally Hinchcliffe (2022)

The unnamed narrator is a disgraced teacher who leaves London for a rental cottage on the Hare House estate in Galloway. Her landlord, Grant Henderson, and his rebellious teenage sister, Cass, are still reeling from the untimely death of their brother. The narrator gets caught up in their lives even though her shrewish neighbour warns her not to. There was a lot that I loved about the atmosphere of this one: the southwest Scotland setting; the slow turn of the seasons as the narrator cycles around the narrow lanes and finds it getting dark earlier, and cold; the inclusion of shape-shifting and enchantment myths; the creepy taxidermy up at the manor house; and the peculiar fainting girls/mass hysteria episode that precipitated the narrator’s banishment and complicates her relationship with Cass. The further you get, the more unreliable you realize this narrator is, yet you keep rooting for her. There are a few too many set pieces involving dead animals, and, overall, perhaps more supernatural influences than are fully explored, but I liked Hinchcliffe’s writing enough to look out for what else she will write. (Readalikes: The Haunting of Hill House and Wakenhyrst)

The unnamed narrator is a disgraced teacher who leaves London for a rental cottage on the Hare House estate in Galloway. Her landlord, Grant Henderson, and his rebellious teenage sister, Cass, are still reeling from the untimely death of their brother. The narrator gets caught up in their lives even though her shrewish neighbour warns her not to. There was a lot that I loved about the atmosphere of this one: the southwest Scotland setting; the slow turn of the seasons as the narrator cycles around the narrow lanes and finds it getting dark earlier, and cold; the inclusion of shape-shifting and enchantment myths; the creepy taxidermy up at the manor house; and the peculiar fainting girls/mass hysteria episode that precipitated the narrator’s banishment and complicates her relationship with Cass. The further you get, the more unreliable you realize this narrator is, yet you keep rooting for her. There are a few too many set pieces involving dead animals, and, overall, perhaps more supernatural influences than are fully explored, but I liked Hinchcliffe’s writing enough to look out for what else she will write. (Readalikes: The Haunting of Hill House and Wakenhyrst)

Metronome by Tom Watson (2022)

Ever since I read Blurb Your Enthusiasm, I’ve been paying more attention to jacket copy. This is an example of a great synopsis that really gives a sense of the plot: mysterious events, suspicion within a marriage, and curiosity about what else might be out there. Aina and Whitney believe they are the only people on their island. They live simply on a croft and hope that, 12 years after their exile, they’ll soon be up for parole. Whitney stubbornly insists they wait for the warden to rescue them, while Aina has given up thinking anyone will ever come. There’s a slight Beckettian air, then, to the first two-thirds of this dystopian novel. When someone does turn up, it’s not who they expect. The eventual focus on parenthood meant this reminded me a lot of The Road; there are also shades of The Water Cure and Doggerland (though, thankfully, the dual protagonists ensure a less overly male atmosphere than in the latter). This was an easy and reasonably intriguing read, but ultimately a bit vague and bleak for me, and not distinguished enough at the level of the prose (e.g., way too many uses of “onside”).

Ever since I read Blurb Your Enthusiasm, I’ve been paying more attention to jacket copy. This is an example of a great synopsis that really gives a sense of the plot: mysterious events, suspicion within a marriage, and curiosity about what else might be out there. Aina and Whitney believe they are the only people on their island. They live simply on a croft and hope that, 12 years after their exile, they’ll soon be up for parole. Whitney stubbornly insists they wait for the warden to rescue them, while Aina has given up thinking anyone will ever come. There’s a slight Beckettian air, then, to the first two-thirds of this dystopian novel. When someone does turn up, it’s not who they expect. The eventual focus on parenthood meant this reminded me a lot of The Road; there are also shades of The Water Cure and Doggerland (though, thankfully, the dual protagonists ensure a less overly male atmosphere than in the latter). This was an easy and reasonably intriguing read, but ultimately a bit vague and bleak for me, and not distinguished enough at the level of the prose (e.g., way too many uses of “onside”).

#NonFicNov Catch-Up 2: Abbs, Hattrick, Powles, DAD Anthology, Santhouse

I’m sneaking in with five more review books on the final day of Nonfiction November, after a first catch-up earlier on in the month. Today I have a sprightly travel book based on the journeys of female writers and artists, a probing account of repeated chronic illness in the family, an anthology of essays showcasing the breadth of fatherhood experiences, a lyrical memoir-in-essays exploring racial identity, and a psychiatrist’s case studies of how the mind influences what the body feels. My apologies to the publishers for the brief responses.

Windswept: Walking in the footsteps of remarkable women by Annabel Abbs

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed Abbs’s novel about Frieda Lawrence and knew she was the subject of the first chapter here. During research for Frieda, Abbs omitted the Lawrences’ six-week honeymoon in the German mountains, so now she makes it a family cycling holiday, imitating Frieda’s experience by walking in a skirt and sunbathing nude. Other chapters follow Welsh painter Gwen John in Bordeaux, Nan Shepherd in Scotland, Georgia O’Keeffe in the American Southwest, and so on. Questions of risk and compulsion recur as Abbs asks how these women sought to achieve liberation. The interplay between biographical information and travel narrative is carefully controlled, but somehow this never quite came together for me in the way that, for instance, Sara Wheeler’s O My America! did.

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed Abbs’s novel about Frieda Lawrence and knew she was the subject of the first chapter here. During research for Frieda, Abbs omitted the Lawrences’ six-week honeymoon in the German mountains, so now she makes it a family cycling holiday, imitating Frieda’s experience by walking in a skirt and sunbathing nude. Other chapters follow Welsh painter Gwen John in Bordeaux, Nan Shepherd in Scotland, Georgia O’Keeffe in the American Southwest, and so on. Questions of risk and compulsion recur as Abbs asks how these women sought to achieve liberation. The interplay between biographical information and travel narrative is carefully controlled, but somehow this never quite came together for me in the way that, for instance, Sara Wheeler’s O My America! did.

(Two Roads, June 2021.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Ill Feelings by Alice Hattrick

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography, Two-Way Mirror), Alice James and Virginia Woolf. All these figures knew that what Hattrick calls “crip time” is different: more elastic; about survival rather than achievement.

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography, Two-Way Mirror), Alice James and Virginia Woolf. All these figures knew that what Hattrick calls “crip time” is different: more elastic; about survival rather than achievement.

The book searches desultorily for answers – could this have something to do with Giardiasis at age two? – but ultimately rests in mystery. ME/CFS patients rarely experience magical recovery, instead exhibiting repeated cycles of illness and being ‘well enough’. Hattrick also briefly considers long Covid as another form of postviral syndrome. My mother had fibromyalgia for years, so I’m always interested to read more about related illnesses. Earlier in the year I read Tracie White’s Waiting for Superman, and this also reminded me of Suzanne O’Sullivan’s books, though it’s literary and discursive rather than scientific.

(Fitzcarraldo Editions, August 2021.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Small Bodies of Water by Nina Mingya Powles

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir, Tiny Moons. She won the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for underrepresented voices in nature writing for this work in progress, and I was eager to read more of her autobiographical essays. Watery metaphors are appropriate for a poet’s fluid narrative about moving between countries and identities. Powles grew up in a mixed-race household in New Zealand with a Malaysian Chinese mother and a white father, and now lives in London after time spent in Shanghai. Water has been her element ever since she learned to swim in a pool in Borneo, where her grandfather was a scholar of freshwater fish.

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir, Tiny Moons. She won the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for underrepresented voices in nature writing for this work in progress, and I was eager to read more of her autobiographical essays. Watery metaphors are appropriate for a poet’s fluid narrative about moving between countries and identities. Powles grew up in a mixed-race household in New Zealand with a Malaysian Chinese mother and a white father, and now lives in London after time spent in Shanghai. Water has been her element ever since she learned to swim in a pool in Borneo, where her grandfather was a scholar of freshwater fish.

The book travels between hemispheres, seasons and languages, and once again food is a major point of reference. “I am the best at being alone when cooking and eating a soft-boiled egg,” she writes. Many of the essays are in short fragments – dated, numbered or titled. A foodstuff or water body (like the ponds at Hampstead Heath) might serve as a link: A kōwhai tree, on which the unofficial national flower of New Zealand grows, when encountered in London, collapses the miles between one home and another. Looking back months later (given I failed to take notes), this evades my grasp; it’s subtle, slippery but admirable.

(Canongate, August 2021.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

DAD: Untold Stories of Fatherhood, Love, Mental Health and Masculinity, edited by Elliott Rae

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on Michael Johnson-Ellis’s essay on surrogacy; I also found particularly insightful R.P. Falconer’s piece on trying to be the best father he can be despite not having a particularly good role model in his own absent father, and Sam Draper’s on breaking the mould as a stay-at-home dad (“the bar for expectations regarding fathers is low, very low”) – I never understood how parental leave works in the UK before reading this. The book is full of genial and relatable stories and half or more of its authors are non-white. It could do with more rigorous editing to get the grammar and writing style up to the standard of traditionally published work, but even for someone like me who is not in the target audience it was an enjoyable set of everyday voices.

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on Michael Johnson-Ellis’s essay on surrogacy; I also found particularly insightful R.P. Falconer’s piece on trying to be the best father he can be despite not having a particularly good role model in his own absent father, and Sam Draper’s on breaking the mould as a stay-at-home dad (“the bar for expectations regarding fathers is low, very low”) – I never understood how parental leave works in the UK before reading this. The book is full of genial and relatable stories and half or more of its authors are non-white. It could do with more rigorous editing to get the grammar and writing style up to the standard of traditionally published work, but even for someone like me who is not in the target audience it was an enjoyable set of everyday voices.

(Music.Football.Fatherhood, June 2021.) With thanks for the free copy for review.

Head First: A Psychiatrist’s Stories of Mind and Body by Alastair Santhouse

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in Pain, Santhouse adopts a biopsychosocial approach: “to focus solely on the scientific and neglect he social aspects of illness is a mistake that we continue to make,” he says. Using a patchwork of anonymous case studies, he delves into topics like depression, altruism, obesity, self-diagnosis, medical mysteries, evidence-based medicine, and preparation for death. A discussion of CFS again echoes the Hattrick. He brings the picture up to date with a final chapter on Covid-19. I’ve read so many doctors’ memoirs that this one didn’t stand out for me at all, but those less familiar with the subject matter could find it a good introduction to some ins and outs of mind–body medicine.

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in Pain, Santhouse adopts a biopsychosocial approach: “to focus solely on the scientific and neglect he social aspects of illness is a mistake that we continue to make,” he says. Using a patchwork of anonymous case studies, he delves into topics like depression, altruism, obesity, self-diagnosis, medical mysteries, evidence-based medicine, and preparation for death. A discussion of CFS again echoes the Hattrick. He brings the picture up to date with a final chapter on Covid-19. I’ve read so many doctors’ memoirs that this one didn’t stand out for me at all, but those less familiar with the subject matter could find it a good introduction to some ins and outs of mind–body medicine.

(Atlantic Books, July 2021.) With thanks to the publicist for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch