Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

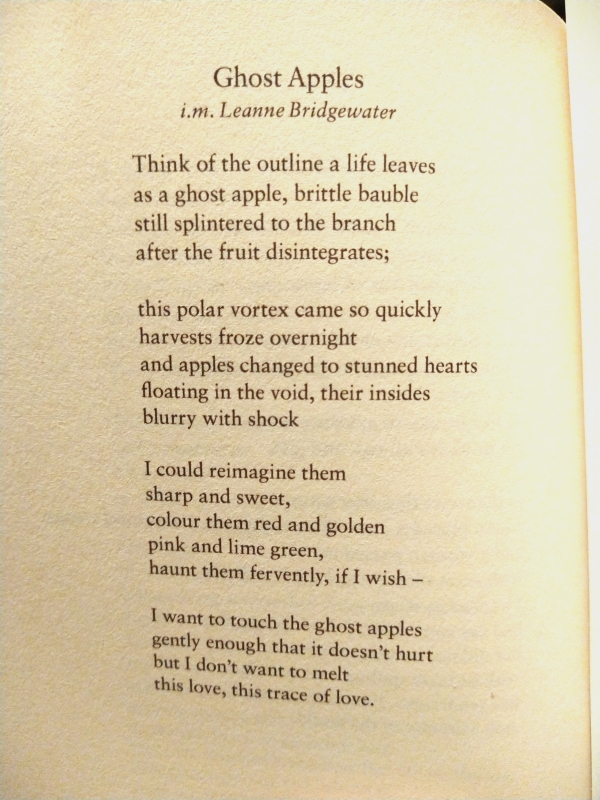

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Three in Translation for #NovNov23: Baek, de Beauvoir, Naspini

I’m kicking off Week 3 of Novellas in November, which we’ve dubbed “Broadening My Horizons.” You can interpret that however you like, but Cathy and I have suggested that you might like to review some works in translation and/or think about any new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas. Literature in translation is still at the edge of my comfort zone, so it’s good to have excuses such as this (and Women in Translation Month each August) to pick up books originally published in another language. Later in the week I’ll have a contribution or two for German Lit Month too.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee (2018; 2022)

[Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur]

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

There are bits of context and reflection, but I didn’t get a clear overall sense of the author as a person, just as a bundle of neuroses. Her psychiatrist tells her “writing can be a way of regarding yourself three-dimensionally,” which explains why I’ve started journaling – that, and I want believe that the everyday matters, and that it’s important to memorialize.

I think the book could have ended with Chapter 14, the note from her psychiatrist, instead of continuing with another 30+ pages of vague self-help chat. This is such an unlikely bestseller (to the extent that a sequel was published, by the same title, just with “Still” inserted!); I have to wonder if some of its charm simply did not translate. (Public library) [194 pages]

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir (2020; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Lauren Elkin]

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Whereas Sylvie loses her Catholic faith (“at one time, I had loved both Andrée and God with ferocity”), Andrée remains devout. She seems destined to follow her older sister, Malou, into a safe marriage, but before that has a couple of unsanctioned romances with her cousin, Bernard, and with Pascal (based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty). Sylvie observes these with a sort of detached jealousy. I expected her obsessive love for Andrée to turn sexual, as in Emma Donoghue’s Learned by Heart, but it appears that it did not, in life or in fiction. In fact, Elkin reveals in a translator’s note that the girls always said “vous” to each other, rather than the more familiar form of you, “tu.” How odd that such stiffness lingered between them.

This feels fragmentary, unfinished. De Beauvoir wrote about Zaza several times, including in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, but this was her fullest tribute. Its length, I suppose, is a fitting testament to a friendship cut short. (Passed on by Laura – thank you!) [137 pages]

(Introduction by Deborah Levy; afterword by Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, de Beavoir’s adopted daughter. North American title: Inseparable.)

Tell Me About It by Sacha Naspini (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford]

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The text is saturated with dialogue; quick wits and sharp tempers blaze. You could imagine this as a radio or stage play. The two characters discuss their children and the town’s scandals, including a lothario turned artist’s muse and a young woman who died by suicide. “The past is full of ghosts. For all of us. That’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be,” Loriano says. There’s a feeling of catharsis to getting all these secrets out into the open. But is there a third person on the line?

A couple of small translation issues hampered my enjoyment: the habit of alternating between calling him Loriano and Bottai (whereas Nives is always that), and the preponderance of sayings (“What’s true is that the business with the nightie has put a bee in my bonnet”), which is presumably to mimic the slang of the original but grates. Still, a good read. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!) [128 pages]

Recommended April Releases by Amy Bloom, Sarah Manguso & Sara Rauch

Just two weeks until moving day – we’ve got a long weekend ahead of us of sanding, painting, packing and gardening. As busy as I am with house stuff, I’m endeavouring to keep up with the new releases publishers have been so good as to send me. Today I review three short works: the story of accompanying a beloved husband to Switzerland for an assisted suicide, a coolly perceptive novella of American girlhood, and a vivid memoir of two momentous relationships. (April was a big month for new books: I have another 6–8 on the go that I’ll be catching up on in the future.) All:

In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Amy Bloom

“We’re not here for a long time, we’re here for a good time.”

(Ameche family saying)

Given the psychological astuteness of her fiction, it’s no surprise that Bloom is a practicing psychotherapist. She treats her own life with the same compassionate understanding, and even though the main events covered in this brilliantly understated memoir only occurred two and a bit years ago, she has remarkable perspective and avoids self-pity and mawkishness. Her husband, Brian Ameche, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in his mid-60s, having exhibited mild cognitive impairment for several years. Brian quickly resolved to make a dignified exit while he still, mostly, had his faculties. But he needed Bloom’s help.

“I worry, sometimes, that a better wife, certainly a different wife, would have said no, would have insisted on keeping her husband in this world until his body gave out. It seems to me that I’m doing the right thing, in supporting Brian in his decision, but it would feel better and easier if he could make all the arrangements himself and I could just be a dutiful duckling, following in his wake. Of course, if he could make all the arrangements himself, he wouldn’t have Alzheimer’s”

U.S. cover

She achieves the perfect tone, mixing black humour with teeth-gritted practicality. Research into acquiring sodium pentobarbital via doctor friends soon hit a dead end and they settled instead on flying to Switzerland for an assisted suicide through Dignitas – a proven but bureaucracy-ridden and expensive method. The first quarter of the book is a day-by-day diary of their January 2020 trip to Zurich as they perform the farce of a couple on vacation. A long central section surveys their relationship – a second chance for both of them in midlife – and how Brian, a strapping Yale sportsman and accomplished architect, gradually descended into confusion and dependence. The assisted suicide itself, and the aftermath as she returns to the USA and organizes a memorial service, fill a matter-of-fact 20 pages towards the close.

Hard as parts of this are to read, there are so many lovely moments of kindness (the letter her psychotherapist writes about Brian’s condition to clinch their place at Dignitas!) and laughter, despite it all (Brian’s endless fishing stories!). While Bloom doesn’t spare herself here, diligently documenting times when she was impatient and petty, she doesn’t come across as impossibly brave or stoic. She was just doing what she felt she had to, to show her love for Brian, and weeping all the way. An essential, compelling read.

With thanks to Granta for the free copy for review.

Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso

I’ve read Manguso’s four nonfiction works and especially love her Wellcome Book Prize-shortlisted medical memoir The Two Kinds of Decay. The aphoristic style she developed in her two previous books continues here as discrete paragraphs and brief vignettes build to a gloomy portrait of Ruthie’s archetypical affection-starved childhood in the fictional Massachusetts town of Waitsfield in the 1980s and 90s. She’s an only child whose parents no doubt were doing their best after emotionally stunted upbringings but never managed to make her feel unconditionally loved. Praise is always qualified and stingily administered. Ruthie feels like a burden and escapes into her imaginings of how local Brahmins – Cabots and Emersons and Lowells – lived. Her family is cash-poor compared to their neighbours and loves nothing more than a trip to the dump: “My parents weren’t after shiny things or even beautiful things; they simply liked getting things that stupid people threw away.”

The depiction of Ruthie’s narcissistic mother is especially acute. She has to make everything about her; any minor success of her daughter’s is a blow to her own ego. I marked out an excruciating passage that made me feel so sorry for this character. A European friend of the family visits and Ruthie’s mother serves corn muffins that he seems to appreciate.

My mother brought up her triumph for years. … She’d believed his praise was genuine. She hadn’t noticed that he’d pegged her as a person who would snatch up any compliment into the maw of her unloved, throbbing little heart.

U.S. cover

At school, as in her home life, Ruthie dissociates herself from every potentially traumatic situation. “My life felt unreal and I felt half-invested. I felt indistinct, like someone else’s dream.” Her friend circle is an abbreviated A–Z of girlhood: Amber, Bee, Charlie and Colleen. “Odd” men – meaning sexual predators – seem to be everywhere and these adolescent girls are horribly vulnerable. Molestation is such an open secret in the world of the novel that Ruthie assumes this is why her mother is the way she is.

While the #MeToo theme didn’t resonate with me personally, so much else did. Chemistry class, sleepovers, getting one’s first period, falling off a bike: this is the stuff of girlhood – if not universally, then certainly for the (largely pre-tech) American 1990s as I experienced them. I found myself inhabiting memories I hadn’t revisited for years, and a thought came that had perhaps never occurred to me before: for our time and area, my family was poor, too. I’m grateful for my ignorance: what scarred Ruthie passed me by; I was a purely happy child. But I think my sister, born seven years earlier, suffered more, in ways that she’d recognize here. This has something of the flavour of Eileen and My Name Is Lucy Barton and reads like autofiction even though it’s not presented as such. The style and contents may well be divisive. I’ll be curious to hear if other readers see themselves in its sketches of childhood.

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

XO by Sara Rauch

Sara Rauch won the Electric Book Award for her short story collection What Shines from It. This compact autobiographical parcel focuses on a point in her early thirties when she lived with a long-time female partner, “Piper”, and had an intense affair with “Liam”, a fellow writer she met at a residency.

“no one sets out in search of buried treasure when they’re content with life as it is”

“Longing isn’t cheating (of this I was certain), even when it brushes its whiskers against your cheek.”

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

This reminded me of a number of books I’ve read about short-lived affairs – Tides, The Instant – and about renegotiating relationships in a queer life – The Fixed Stars, In the Dream House – but felt most like reading a May Sarton journal for how intimately it recreates daily routines of writing, cooking, caring for cats, and weighing up past, present and future. Lovely stuff.

With thanks to publicist Lori Hettler and Autofocus Books for the e-copy for review.

Will you seek out one or more of these books?

What other April releases can you recommend?

Iris Murdoch Readalong: The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974)

A later Murdoch – her sixteenth novel – and not one I knew anything about beforehand. In terms of atmosphere, characters and themes, it struck me as a cross between A Severed Head and The Nice and the Good. Like the former, it feels like a play with a few recurring sets: Hood House, where the Gavenders (Blaise, Harriet and David) live; their next-door neighbor Montague Small’s house; and the apartment where Blaise keeps his mistress, Emily McHugh, and their eight-year-old son Luca. A sizeable dramatis personae radiates out from the central love triangle: lodgers, neighbors, other family members, mutual friends and quite a few dogs.

Blaise is a psychoanalyst but considers himself a charlatan because he has no medical degree; he’s considering returning to his studies to rectify that. Harriet reminded me of Kate from The Nice and the Good: a cheerful, only mildly unfulfilled matriarch who is determined to choreograph much of what happens around her. (“She wanted simply to feel the controls firmly in her hands. She wanted to be the recognizer, the authorizer, the welcomer-in, the one who made things respectable and made them real by her cognizance of them.”) Their son David, 16, looks like a Pre-Raphaelite god and is often disgusted by fleshly reality. Montague writes successful but formulaic detective novels and is mourning his wife’s recent death.

I loved how on first introduction to most characters we hear about the dreams from which they’ve just awoken, involving mermaids, cats, dogs and a monster with a severed head. “Dreams are rather marvellous, aren’t they,” David remarks to Monty. “They can be beautiful in a special way like nothing else. Even awful things in dreams have style.” Scenes often open with dreams that feel so real to the characters that they could fool readers into belief.

Blaise knows he can’t sustain his double life, especially after Luca stows away in his car on a couple of occasions to see Hood House. When he confesses to Harriet via a letter, she seems to handle things very well. In fact, she almost glows with self-righteous pride over how reasonably she’s been responding. But both she and Emily end up resentful. Why should Blaise ‘win’ by keeping his wife and his mistress? “You must feel like the Sultan of Turkey,” Emily taunts him. “You’ve got us both. You’ve got away with it.” Here starts a lot of back-and-forth, will-they-won’t-they that gets somewhat tedious. Throughout I noticed overlong sections of internal monologue and narrator commentary on relationships.

There’s a misperception, I think, that Murdoch wrote books in which not much happens, simply because her canvas can be small and domestically oriented. However, this is undoubtedly an eventful novel, including a Shocking Incident that Liz warned about. Foreshadowing had alerted me that someone was going to die, but it wasn’t who or how I thought. When it comes to it, Murdoch is utterly matter-of-fact: “[X] had perished”.

There’s a misperception, I think, that Murdoch wrote books in which not much happens, simply because her canvas can be small and domestically oriented. However, this is undoubtedly an eventful novel, including a Shocking Incident that Liz warned about. Foreshadowing had alerted me that someone was going to die, but it wasn’t who or how I thought. When it comes to it, Murdoch is utterly matter-of-fact: “[X] had perished”.

One of the pleasures of reading a Murdoch novel is seeing how she reworks the same sorts of situations and subjects. (Liz has written a terrific review set in the context of Murdoch’s whole body of work.) Here I enjoyed tracing the mother–son relationships – at least three of them, two of which are quite similar: smothering and almost erotic. Harriet later tries to subsume Luca into the family, too. I also looked out for the recurring Murdochian enchanter figure: first Blaise, for whom psychiatry is all about power, and then Harriet.

I hugely enjoyed the first 100 pages or more of the book, but engaged with it less and less as it went on. Ultimately, it falls somewhere in the middle for me among the Murdochs I’ve read. Here’s my ranking of the nine novels I’ve read so far, with links to my reviews:

Favorite: The Bell

The Sea, The Sea

The Sacred and Profane Love Machine

The Black Prince

Least favorite: An Accidental Rose

My rating:

A favorite passage (this is Monty on the perils of working from home!): “If I had an ordinary job to do I’d have to get on with it. Being self-employed I can brood all day. It’s undignified and bad.”

This is the last of the Murdoch paperbacks I bought as a bargain bundle from Oxfam Books some years ago. I’ll leave it a while – perhaps a year – and then try some earlier Murdochs I’ve been tempted by during Liz’s Iris Murdoch readalong project, such as The Unicorn.

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of

That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to

That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor.

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor. This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed  “My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,  I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,  Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on  Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

This was my first taste of Baldwin’s fiction, and it was very good indeed. David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée – Hella, who’s traveling in Spain. It seems that David had bisexual tendencies but went off women after Giovanni. “Much has been written of love turning to hatred, of the heart growing cold with the death of love.” We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but all through Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he is sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave. I’ll make Go Tell It on the Mountain my next one by Baldwin.

This was my first taste of Baldwin’s fiction, and it was very good indeed. David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée – Hella, who’s traveling in Spain. It seems that David had bisexual tendencies but went off women after Giovanni. “Much has been written of love turning to hatred, of the heart growing cold with the death of love.” We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but all through Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he is sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave. I’ll make Go Tell It on the Mountain my next one by Baldwin.  Garfield, Why Do You Hate Mondays? by Jim Davis (1982)

Garfield, Why Do You Hate Mondays? by Jim Davis (1982)

This is a collected comic strip that appeared on Instagram between 2016 and 2018 (you can view it in full

This is a collected comic strip that appeared on Instagram between 2016 and 2018 (you can view it in full

I was curious about this bestselling fable, but wish I’d left it to its 1970s oblivion. The title seagull stands out from the flock for his desire to fly higher and faster than seen before. He’s not content to be like all the rest; once he arrives in birdie heaven he starts teaching other gulls how to live out their perfect freedom. “We can lift ourselves out of ignorance, we can find ourselves as creatures of excellence and intelligence and skill.” Gradually comes the sinking realization that JLS is a Messiah figure. I repeat, the seagull is Jesus. (“They are saying in the Flock that if you are not the Son of the Great Gull Himself … then you are a thousand years ahead of your time.”) An obvious allegory, unlikely dialogue, dated metaphors (“like a streamlined feathered computer”), cringe-worthy New Age sentiments and loads of poor-quality soft-focus photographs: This was utterly atrocious.

I was curious about this bestselling fable, but wish I’d left it to its 1970s oblivion. The title seagull stands out from the flock for his desire to fly higher and faster than seen before. He’s not content to be like all the rest; once he arrives in birdie heaven he starts teaching other gulls how to live out their perfect freedom. “We can lift ourselves out of ignorance, we can find ourselves as creatures of excellence and intelligence and skill.” Gradually comes the sinking realization that JLS is a Messiah figure. I repeat, the seagull is Jesus. (“They are saying in the Flock that if you are not the Son of the Great Gull Himself … then you are a thousand years ahead of your time.”) An obvious allegory, unlikely dialogue, dated metaphors (“like a streamlined feathered computer”), cringe-worthy New Age sentiments and loads of poor-quality soft-focus photographs: This was utterly atrocious.

In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. He’s so jaded that he barely listens to his patients anymore. “Was I just lazy, or was I genuinely so arrogant that I’d become bored by other people’s misery?” he asks himself. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy: learning that his longtime secretary’s husband has terminal cancer and visiting the man for some straight talk about death; discovering that the neighbor he’s never met, but only known via piano playing through the wall, is deaf, and striking up a friendship with him; and meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm, and vowing to get to the bottom of her trauma. This debut novel by a psychologist (and table tennis champion) is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. He’s so jaded that he barely listens to his patients anymore. “Was I just lazy, or was I genuinely so arrogant that I’d become bored by other people’s misery?” he asks himself. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy: learning that his longtime secretary’s husband has terminal cancer and visiting the man for some straight talk about death; discovering that the neighbor he’s never met, but only known via piano playing through the wall, is deaf, and striking up a friendship with him; and meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm, and vowing to get to the bottom of her trauma. This debut novel by a psychologist (and table tennis champion) is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.  Daniel is a recently widowed farmer in rural Wales. On his own for the challenges of lambing, he hates who he’s become. “She would not have liked this anger in me. I was not an angry man.” In the meantime, a badger-baiter worries the police are getting wise to his nocturnal misdemeanors and looks for a new, remote locale to dig for badgers. I kept waiting for these two story lines to meet explosively, but instead they just fizzle out. I should have been prepared for the animal cruelty I’d encounter here, but it still bothered me. Even the descriptions of lambing, and of Daniel’s wife’s death, are brutal. Jones’s writing reminded me of Andrew Michael Hurley’s; while I did appreciate the observation that violence begets more violence in groups of men (“It was the gangness of it”), this was a tough read for me.

Daniel is a recently widowed farmer in rural Wales. On his own for the challenges of lambing, he hates who he’s become. “She would not have liked this anger in me. I was not an angry man.” In the meantime, a badger-baiter worries the police are getting wise to his nocturnal misdemeanors and looks for a new, remote locale to dig for badgers. I kept waiting for these two story lines to meet explosively, but instead they just fizzle out. I should have been prepared for the animal cruelty I’d encounter here, but it still bothered me. Even the descriptions of lambing, and of Daniel’s wife’s death, are brutal. Jones’s writing reminded me of Andrew Michael Hurley’s; while I did appreciate the observation that violence begets more violence in groups of men (“It was the gangness of it”), this was a tough read for me.  This seems destined to be in many a bibliophile’s Christmas stocking this year. It’s a collection of mini-essays, quotations and listicles on topics such as DNFing, merging your book collection with a new partner’s, famous bibliophiles and bookshelves from history, and how you choose to organize your library. It’s full of fun trivia. Two of my favorite factoids: Bill Clinton keeps track of his books via a computerized database, and the original title of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was “I Have Committed Fornication but that Was in Another Country” (really?!). It’s scattered and shallow, but fun in the same way that Book Riot articles generally are. (I almost always click through to 2–5 articles in my Book Riot e-newsletters, so that’s no problem in my book.) I couldn’t find a single piece of information on ‘Annie Austen’, not even a photo – I sincerely doubt she’s that Kansas City lifestyle blogger, for instance – so I suspect she’s actually a collective of interns.

This seems destined to be in many a bibliophile’s Christmas stocking this year. It’s a collection of mini-essays, quotations and listicles on topics such as DNFing, merging your book collection with a new partner’s, famous bibliophiles and bookshelves from history, and how you choose to organize your library. It’s full of fun trivia. Two of my favorite factoids: Bill Clinton keeps track of his books via a computerized database, and the original title of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was “I Have Committed Fornication but that Was in Another Country” (really?!). It’s scattered and shallow, but fun in the same way that Book Riot articles generally are. (I almost always click through to 2–5 articles in my Book Riot e-newsletters, so that’s no problem in my book.) I couldn’t find a single piece of information on ‘Annie Austen’, not even a photo – I sincerely doubt she’s that Kansas City lifestyle blogger, for instance – so I suspect she’s actually a collective of interns.

This posthumous collection brings together essays Broyard wrote for the New York Times after being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer in 1989, journal entries, a piece he’d written after his father’s death from bladder cancer in 1954, and essays from the early 1980s about “the literature of death.” He writes to impose a narrative on his illness, expatiating on what he expects of his doctor and how he plans to live with style even as he’s dying. “If you have to die, and I hope you don’t, I think you should try to die the most beautiful death you can,” he charmingly suggests. It’s ironic that he laments a dearth of literature (apart from Susan Sontag) about illness and dying – if only he could have seen the flourishing of cancer memoirs in the last two decades! [An interesting footnote: in 2007 Broyard’s daughter Bliss published a memoir, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets, about finding out that her father was in fact black but had passed as white his whole life. I’ll be keen to read that.]

This posthumous collection brings together essays Broyard wrote for the New York Times after being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer in 1989, journal entries, a piece he’d written after his father’s death from bladder cancer in 1954, and essays from the early 1980s about “the literature of death.” He writes to impose a narrative on his illness, expatiating on what he expects of his doctor and how he plans to live with style even as he’s dying. “If you have to die, and I hope you don’t, I think you should try to die the most beautiful death you can,” he charmingly suggests. It’s ironic that he laments a dearth of literature (apart from Susan Sontag) about illness and dying – if only he could have seen the flourishing of cancer memoirs in the last two decades! [An interesting footnote: in 2007 Broyard’s daughter Bliss published a memoir, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets, about finding out that her father was in fact black but had passed as white his whole life. I’ll be keen to read that.]  This was a random 50p find at the Hay-on-Wye market on our last trip. In July 1940 Kipps adopted a house sparrow that had fallen out of the nest – or, perhaps, been thrown out for having a deformed wing and foot. Clarence became her beloved pet, living for just over 12 years until dying of old age. A former professional musician, Kipps served as an air-raid warden during the war; she and Clarence had a couple of close shaves and had to evacuate London at one point. Clarence sang more beautifully than the average sparrow and could do a card trick and play dead. He loved to nestle inside Kipps’s blouse and join her for naps under the duvet. At age 11 he had a stroke, but vet attention (and champagne) kept him going for another year, though with less vitality. This is sweet but not saccharine, and holds interest for its window onto domesticated birds’ behavior. With photos, and a foreword by Julian Huxley.

This was a random 50p find at the Hay-on-Wye market on our last trip. In July 1940 Kipps adopted a house sparrow that had fallen out of the nest – or, perhaps, been thrown out for having a deformed wing and foot. Clarence became her beloved pet, living for just over 12 years until dying of old age. A former professional musician, Kipps served as an air-raid warden during the war; she and Clarence had a couple of close shaves and had to evacuate London at one point. Clarence sang more beautifully than the average sparrow and could do a card trick and play dead. He loved to nestle inside Kipps’s blouse and join her for naps under the duvet. At age 11 he had a stroke, but vet attention (and champagne) kept him going for another year, though with less vitality. This is sweet but not saccharine, and holds interest for its window onto domesticated birds’ behavior. With photos, and a foreword by Julian Huxley.

Mayne was vicar at the university church in Cambridge when he came down with a mysterious, debilitating illness, only later diagnosed as myalgic encephalomyelitis or post-viral fatigue syndrome. During his illness he was offered the job of Dean of Westminster, and accepted the post even though he worried about his ability to carry out his duties. He writes of his frustration at not getting better and receiving no answers from doctors, but much of this short memoir is – unsurprisingly, I suppose – given over to theological musings on the nature of suffering, with lots of quotations (too many) from theologians and poets. Curiously, he also uses Broyard’s word, speaking of the “intoxication of convalescence.”

Mayne was vicar at the university church in Cambridge when he came down with a mysterious, debilitating illness, only later diagnosed as myalgic encephalomyelitis or post-viral fatigue syndrome. During his illness he was offered the job of Dean of Westminster, and accepted the post even though he worried about his ability to carry out his duties. He writes of his frustration at not getting better and receiving no answers from doctors, but much of this short memoir is – unsurprisingly, I suppose – given over to theological musings on the nature of suffering, with lots of quotations (too many) from theologians and poets. Curiously, he also uses Broyard’s word, speaking of the “intoxication of convalescence.”  The author has a PhD in religion and art and produced sculptures for a Benedictine abbey in British Columbia and the Peace Museum in Hiroshima. I worried this would be too New Agey for me, but at 20p from a closing-down charity shop, it was worth taking a chance on. Nerburn feels we are often too “busy with our daily obligations … to surround our hearts with the quiet that is necessary to hear life’s softer songs.” He tells pleasant stories of moments when he stopped to appreciate meaning and connection, like watching a man in a wheelchair fly a kite, setting aside his to-do list to have coffee with an ailing friend, and attending the funeral of a Native American man he once taught.

The author has a PhD in religion and art and produced sculptures for a Benedictine abbey in British Columbia and the Peace Museum in Hiroshima. I worried this would be too New Agey for me, but at 20p from a closing-down charity shop, it was worth taking a chance on. Nerburn feels we are often too “busy with our daily obligations … to surround our hearts with the quiet that is necessary to hear life’s softer songs.” He tells pleasant stories of moments when he stopped to appreciate meaning and connection, like watching a man in a wheelchair fly a kite, setting aside his to-do list to have coffee with an ailing friend, and attending the funeral of a Native American man he once taught.