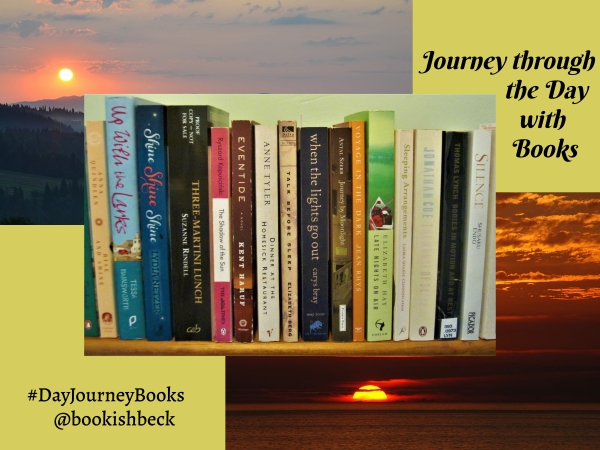

October Reading Plans

My plans for the rest of the month’s reading, in pictures.

A handful of October releases (not counting the ones I’ve reviewed in advance for Shelf Awareness et al., one for a blog tour, or what I’ll be reading for November deadlines).

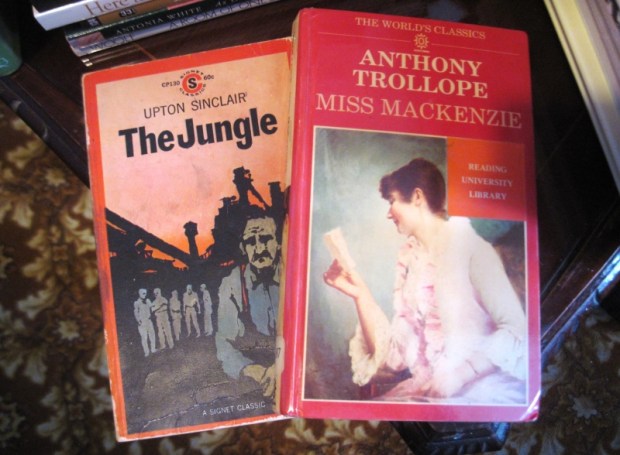

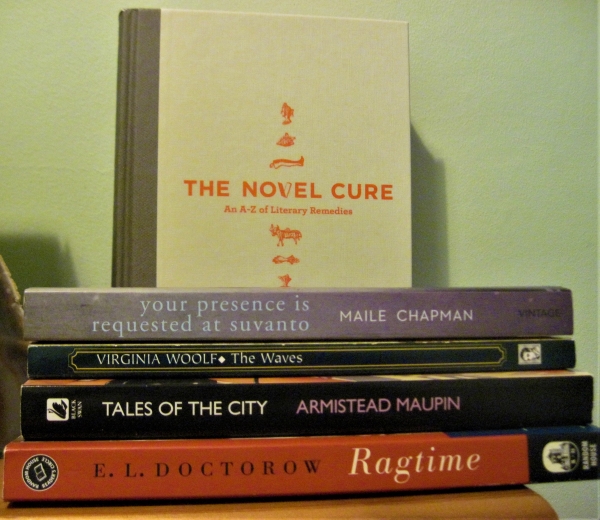

I turn 40 on the 14th, so have made a halfhearted attempt to gather my last four unread from The Novel Cure’s books to read in your thirties before that milestone passes. Whether I’ll actually read them, I’m less sure about. I’ve owned this copy of The Jungle for decades; I’ve not enjoyed Trollope since my student days. Time runs short, anyway, but I’ll see how I get on with the Sinclair at least, and perhaps skim the Trollope to get a sense of why Berthoud and Elderkin chose it for that list.

[The others are London Fields by Martin Amis, which is on loan just as I need it, and The Best of It All by Rona Jaffe, which I borrowed once and didn’t get far in; now it appears to have been withdrawn from the system. (My DNF review from 2018: “I read the first chapter and had a weird reverse case of déjà vu: this is awfully similar to Mad Men, Suzanne Rindell’s Three-Martini Lunch, and A.J. Pearce’s Dear Mrs Bird, though of course they would have been based on Jaffe’s novel rather than the other way round. Caroline Bender, fresh out of a broken engagement, arrives for her first day as a typist at a New York City publishing house and has to adjust to the catty office politics. I think I’ll truly enjoy this, but I need to find another time when I can give it my full attention. It’s nearly 450 pages of small print, so I need a chunk of time when I can really sink into it, like a flight or a long train ride.)]

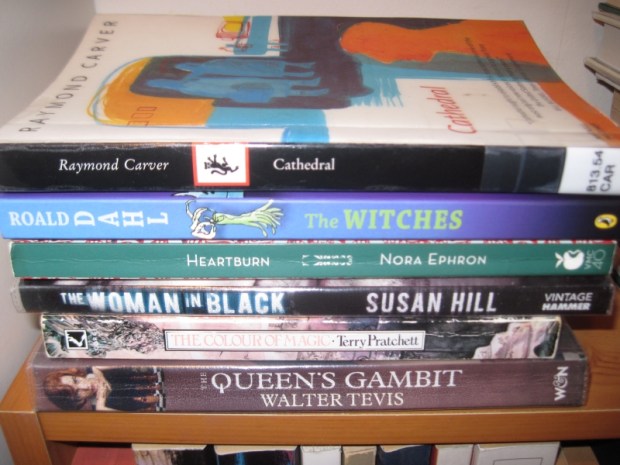

Also in conjunction with that big birthday, I’ve collected some notable 1983 releases, including 5 out of the 10 most popular on Goodreads’ list. (The Ephron and Hill would be rereads for me.) I’ll work on them in these last few months of the year.

A lesser-known Margaret Drabble novel for our women’s classics book club subgroup; Pale Fire for 1962 Club; two potential books for AusReading Month.

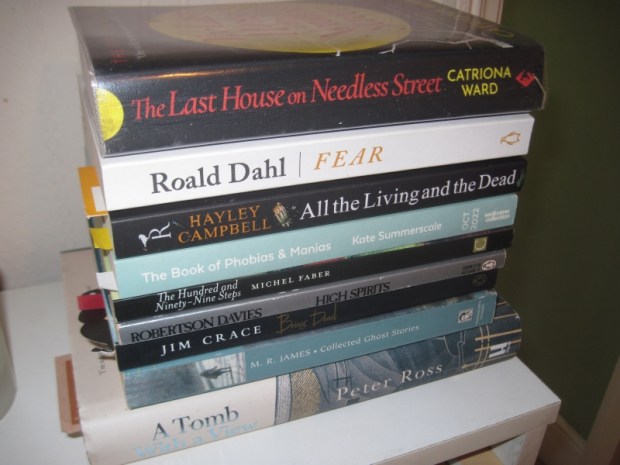

Some spooky or death-themed R.I.P. options (I know the challenge technically starts in September, but I only ever think to read such books as Halloween approaches).

I’ll be spending my birthday weekend in Hay-on-Wye, one of my special places. Here’s my Wales-themed and/or Hay-related pile. I’ll take all of these and probably many of the above as well; I like to have lots to choose from!

First Four in a Row: Márai, Maupin, McEwan, McKay

I announced a few new TBR reading projects back in May 2020, including a Four in a Row Challenge (see the ‘rules’, such as they are, in my opening post). It only took me, um, nearly 11 months to complete a first set! The problem was that I kept changing my mind on which four to include and acquiring more that technically should go into the sequence, e.g. McCracken, McGregor; also, I stalled on the Maupin for ages. But here we are at last. Debbie, meanwhile, took up the challenge and ran with it, completing a set of four novels – also by M authors, clearly a numerous and tempting bunch – back in October. Here’s hers.

I’m on my way to completing a few more sets: I’ve read one G, one and a bit H, and I selected a group of four L. I’ve not chosen a nonfiction quartet yet, but that could be an interesting exercise: I file by author surname even within categories like science/nature and travel, so this could throw up interesting combinations of topics. Do feel free to join in this challenge if, like me, you could use a push to get through more of the books on your shelves.

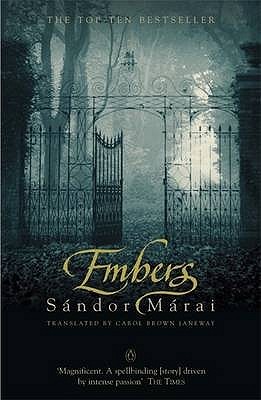

Embers by Sándor Márai (1942)

[Translated from the Hungarian by Carol Brown Janeway]

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

Henrik was 10 when he met Konrad at an academy school. They were soon the best of friends, but two things came between them: first was the difference in their backgrounds (“each forgave the other’s original sin: wealth on the one hand and poverty on the other”); second was their love for the same woman.

I appreciated the different setup to this one – a male friendship, just a few very old characters, the probing of the past through memory and dialogue – but it was so languid that I struggled to stay engaged with the plot.

*My next will be Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, another charity shop find.

Favourite lines:

“My homeland was a feeling, and that feeling was mortally wounded.”

“Life becomes bearable only when one has come to terms with who one is, both in one’s own eyes and in the eyes of the world.”

Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (1978)

I’d picked this up from the free bookshop we used to have in the local mall (the source of my next two as well) and started it during Lockdown #1 because in The Novel Cure it is given as a prescription for Loneliness. Berthoud and Elderkin suggest it can make you feel like part of a gang of old friends, and it’s “as close to watching television as literature gets” due to the episodic format – the first four Tales books were serialized in the San Francisco Chronicle.

How I love a perfect book and bookmark combination!

The titled chapters are each about three pages long, which made it an ideal bedside book – I would read a chapter per night before sleep. The issue with this piecemeal reading strategy, though, was that I never got to know any of the characters; because I’d often only pick up the book once a week or so, I forgot who people were and what was going on. That didn’t stop individual vignettes from being entertaining, but meant it didn’t all come together for me.

Maupin opens on Mary Ann Singleton, a 25-year-old secretary who goes to San Francisco on vacation and impulsively decides to stay. She rooms at Anna Madrigal’s place on Barbary Lane and meets a kooky assortment of folks, many of them gay – including her new best friend, Michael Tolliver, aka “Mouse.” There are parties and affairs, a pregnancy and a death, all told with a light touch and a clear love for the characters; dialogue predominates. While it’s very much of its time, it manages not to feel too dated overall. I can see why many have taken the series to heart, but don’t think I’ll go further with Maupin’s work.

Note: Long before I tried the book, I knew about it through one of my favourite Bookshop Band songs, “Cleveland,” which picks up on Mary Ann’s sense of displacement as she ponders whether she’d be better off back in Ohio after all. Selected lyrics:

Quaaludes and cocktails

A story book lane

A girl with three names

A place, post-Watergate

Freed from its bird cage

Where the unafraid parade

[…]

Perhaps, we should all

Go back to Cleveland

Where we know what’s around the bend

[…]

Citizens of Atlantis

The Madrigal Enchantress cries

And we decide, to stay and bide our time

On this far-out, far-flung peninsula.

The Children Act by Ian McEwan (2014)

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW]

She rules that the doctors should go ahead with the treatment. “He must be protected from his religion and from himself.” Adam, now better but adrift from the religion he was raised in, starts stalking Fiona and sending her letters and poems. Estranged from her husband, who wants her to condone his affair with a young colleague, and fond of Adam, Fiona spontaneously kisses the young man while traveling for work near Newcastle. But thereafter she ignores his communications, and when he doesn’t seek treatment for his recurring cancer and dies, she blames herself.

[END OF SPOILERS]

It’s worth noting that the AI in McEwan’s most recent full-length novel, Machines Like Me, is also named Adam, and in both books there’s uncertainty about whether the Adam character is supposed to be a child substitute.

The Birth House by Ami McKay (2006)

Dora is the only daughter to be born into the Rare family of Nova Scotia’s Scots Bay in five generations. At age 17, she becomes an apprentice to Marie Babineau, a Cajun midwife and healer who relies on ancient wisdom and appeals to the Virgin Mary to keep women safe and grant them what they want, whether that’s a baby or a miscarriage. As the 1910s advance and the men of the village start leaving for the war, the old ways represented by Miss B. and Dora come to be seen as a threat. Dr. Thomas wants women to take out motherhood insurance and commit to delivering their babies at the new Canning Maternity Home with the help of chloroform and forceps. “Why should you ladies continue to suffer, most notably the trials of childbirth, when there are safe, modern alternatives available to you?” he asks.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

There are a few places where the narrative is almost overwhelmed by all the (admittedly, fascinating) facts McKay, a debut author, turned up in her research, and where the science versus superstition dichotomy seems too simplistic, but for the most part this was just the sort of absorbing, atmospheric historical fiction that I like best. McKay took inspiration from her own home, an old birthing house in the Bay of Fundy.

Classic of the Month: The Rector’s Daughter by F.M. Mayor

I sought this out because Susan Hill hails it as a forgotten classic and it’s included on a list of books to read in your thirties in The Novel Cure.* It’s a gentle and rather melancholy little 1924 novel about Mary, the plain, unmarried 35-year-old daughter of elderly Canon Jocelyn, a clergyman in the undistinguished East Anglian village of Dedmayne. “On the whole she was happy. She did not question the destiny life brought her. People spoke pityingly of her, but she did not feel she required pity.” That is, until she unexpectedly falls in love. We follow Mary for the next four years and see how even a seemingly small life can have an impact.

I expect Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin chose this as a book for one’s thirties because it’s about a late bloomer who hasn’t acquired the expected spouse and children and harbors secret professional ambitions. The struggle to find common ground with an ageing parent is a strong theme, as is the danger of an unequal marriage. Best not to say too much more about the plot itself, but I’d recommend this to readers of Elizabeth Taylor. I was also reminded strongly at points of A Jest of God by Margaret Laurence and Tender Is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s a short and surprising classic, one well worth rediscovering.

I expect Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin chose this as a book for one’s thirties because it’s about a late bloomer who hasn’t acquired the expected spouse and children and harbors secret professional ambitions. The struggle to find common ground with an ageing parent is a strong theme, as is the danger of an unequal marriage. Best not to say too much more about the plot itself, but I’d recommend this to readers of Elizabeth Taylor. I was also reminded strongly at points of A Jest of God by Margaret Laurence and Tender Is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s a short and surprising classic, one well worth rediscovering.

Some favorite lines:

- “she had written almost as a silkworm weaves a cocoon, with no thought of admiration.”

- “after three years in one place, suburban people, whatever their layer in society, become restless and want to move on.”

- “She had found self-pity a quagmire in which it was difficult not to be submerged.”

My rating:

Note: Flora Macdonald Mayor (1872–1932) published four novels and a short story collection. Her life story is vaguely similar to Mary Jocelyn’s in that she was the daughter of a Cambridge clergyman.

*I’ve now read six of the 10 titles on their list. The remaining four, which I’ll probably try to read by the end of next year, are London Fields by Martin Amis, The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, The Jungle by Upton Sinclair, and Miss Mackenzie by Anthony Trollope. I own the Sinclair in paperback, the Jaffe is on shelf at my local public library, and I can get the Amis and Trollope from the university library any time.

National Poetry Day: William Sieghart’s The Poetry Pharmacy

Today is National Poetry Day in the UK, and there could be no better primer for reluctant poetry readers than William Sieghart’s The Poetry Pharmacy. Consider it the verse equivalent of Berthoud and Elderkin’s The Novel Cure: an accessible and inspirational guide that suggests the right piece at the right time to help heal a particular emotional condition.

Sieghart, a former chairman of the Arts Council Lottery Panel, founded the Forward Prizes for Poetry in 1992 and National Poetry Day itself in 1994. He’s active in supporting public libraries and charities, but he’s also dedicated to giving personal poetry prescriptions, and has taken his Poetry Pharmacy idea to literary festivals, newspapers and radio programs.

Under five broad headings, this short book covers everything from Anxiety and Convalescence to Heartbreak and Regret. I most appreciated the discussion of slightly more existential states, such as Feelings of Unreality, for which Sieghart prescribes a passage from John Burnside’s “Of Gravity and Light,” about the grounding Buddhist monks find in menial tasks. Pay attention to life’s everyday duties, the poem teaches, and higher insights will come.

I also particularly enjoyed Julia Darling’s “Chemotherapy”—

I never thought that life could get this small,

that I would care so much about a cup,

the taste of tea, the texture of a shawl,

and whether or not I should get up.

and “Although the wind” by Izumi Shikibu:

Although the wind

blows terribly here,

the moonlight also leaks

between the roof planks

of this ruined house.

Sieghart has chosen a great variety of poems in terms of time period and register. Rumi and Hafez share space with Wendy Cope and Maya Angelou. Of the 56 poems, I’d estimate that at least three-quarters are from the twentieth century or later. At times the selections are fairly obvious or clichéd (especially “Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep” for Bereavement), and the choice of short poems or excerpts seems to pander to short attention spans. So populist is the approach that Sieghart warns Keats is the hardest of all. I also thought there should have been a strict one poem per poet rule; several get two or even three entries.

If put in the right hands, though, this book will be an ideal introduction to the breadth of poetry out there. It would be a perfect Christmas present for the person in your life who always says they wish they could appreciate poetry but just don’t know where to start or how to understand it. Readers of a certain age may get the most out of the book, as a frequently recurring message is that it’s never too late to change one’s life and grow in positive ways.

“What people need more than comfort is to be given a different perspective on their inner turmoil. They need to reframe their narrative in a way that leaves room for happiness and gratitude,” Sieghart writes. Poetry is a perfect way to look slantwise at truth (to paraphrase Emily Dickinson) and change your perceptions about life. If you’re new to poetry, pick this up at once; if you’re an old hand, maybe buy it for someone else and have a quick glance through to discover a new poet or two.

My rating:

My thanks to Particular Books for the free copy for review.

Do you turn to poetry when you’re struggling with life? Does it help?

Related reading:

Books I’ve read and enjoyed:

- The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner

- 52 Ways of Looking at a Poem by Ruth Padel

- The Poem and the Journey and 60 Poems to Read Along the Way by Ruth Padel

Currently reading: Why Poetry by Matthew Zapruder

On the TBR:

- Poetry Will Save Your Life: A Memoir by Jill Bialosky

- How to Read a Poem by Molly Peacock

Classic of the Month: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Thank you to those who recommended Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) as my classic for March. I’m glad I read it, not least because, like Narcissism for Beginners, it’s an epistolary within an epistolary – bonus! I imagine most of my readers will already be familiar with the basic plot, but if you’re determined to avoid spoilers you’ll want to look away from my second through fourth paragraphs.

The chronology and structure of the novel struck me as very sophisticated: in 1847, gentleman farmer Gilbert Markham is writing a detailed letter to a friend, describing how he fell in love with the widow Helen Graham – the new tenant at Wildfell Hall, a painter who’s living there in secret – starting in the autumn of 1827. (I even wondered if this could have been one of the earliest instances of a female author writing from a male point-of-view.) Their interrupted and seemingly ill-fated courtship reminded me of Lizzy and Darcy’s in Pride and Prejudice: Gilbert initially thinks Helen stubborn and argumentative, especially in how she refuses to accept neighbors’ advice on how to raise her young son, Arthur. Gradually, though, he comes to be captivated by this intelligent and outspoken young woman on whose “lofty brow … thought and suffering seem equally to have stamped their impress.”

The chronology and structure of the novel struck me as very sophisticated: in 1847, gentleman farmer Gilbert Markham is writing a detailed letter to a friend, describing how he fell in love with the widow Helen Graham – the new tenant at Wildfell Hall, a painter who’s living there in secret – starting in the autumn of 1827. (I even wondered if this could have been one of the earliest instances of a female author writing from a male point-of-view.) Their interrupted and seemingly ill-fated courtship reminded me of Lizzy and Darcy’s in Pride and Prejudice: Gilbert initially thinks Helen stubborn and argumentative, especially in how she refuses to accept neighbors’ advice on how to raise her young son, Arthur. Gradually, though, he comes to be captivated by this intelligent and outspoken young woman on whose “lofty brow … thought and suffering seem equally to have stamped their impress.”

And indeed, at the heart of Gilbert’s narrative is a lengthy journal by Helen herself, starting in 1821, explaining the misfortune that drove her to take refuge in the isolation of Wildfell Hall. For, as in Anne’s sister Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, there’s an impediment to the marriage of true minds in the form of a living spouse. Helen is still tied to Arthur Huntingdon, a dissolute alcoholic she married against her family’s advice and has ever since longed to see reformed. In a phrase I was highly bemused to see in use in the middle of the nineteenth century, she defends him thusly: “if I hate the sins I love the sinner, and would do much for his salvation.” The novel’s religious language may feel outdated in places, but the imagined psyche of a woman who stays with an abusive or at least neglectful partner is spot on.

For the most part I enjoyed the story line, but I must confess that I wearied of Helen’s 260-page account, filled as it is with repetitive instances of her incorrigibly loutish husband’s carousing. I had a bit too much of her melodrama and goody-goody moralizing, such that it felt like a relief to finally get back to Gilbert’s voice. The last 100 pages, though, and particularly the last few chapters, are wonderful and race by. I loved this late metaphor for Helen’s chastened beauty:

This rose is not so fragrant as a summer flower, but it has stood through hardships none of them could bear. The cold rain of winter has sufficed to nourish it, and its faint sun to warm it; the bleak winds have not blanched it or broken its stem, and the keen frost has not blighted it. Look, … it is still fresh and blooming as a flower can be, with the cold snow even now on its petals.

Anne Brontë c. 1834, painted by Patrick Branwell Brontë [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons (restored version).

As always, I’m dumbfounded by the Brontës’ profound understanding of human motivation and romantic love given their sheltered upbringing. Theirs were wild hearts. I’ll always be a Charlotte fan first and foremost, but I was delighted with my first experience of Anne’s work and look forward to trying Agnes Grey in the near future.

Lest you think Victorian literature is all po-faced, righteous ruminating, I’ll end with my favorite funny quote from the book. This is from Gilbert’s snide, sporty brother Fergus (I wish he’d had a larger role!), seeming to mock Jane Austen with this joke about needing to know everything about Helen Graham as soon as she arrives in town:

“mind you bring me word how much sugar she puts in her tea, and what sort of caps and aprons she wears, and all about it, for I don’t know how I can live till I know,” said Fergus very gravely. But if he intended the speech to be hailed as a masterstroke of wit, he signally failed, for nobody laughed. However, he was not much disconcerted at that; for when he had taken a mouthful of bread and butter, and was about to swallow a gulp of tea, the humour of the thing burst upon him with such irresistible force that he was obliged to jump up from the table, and rush snorting and choking from the room.

My rating:

Next month: Eleanor of Elle Thinks recommends Our Mutual Friend as the book that will finally get me back into Dickens, so I plan to make it do double duty as my Classic and Doorstopper for April.

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue (2000): A slammerkin was, in eighteenth-century parlance, a loose gown or a loose woman. Donoghue was inspired by the bare facts about Mary Saunders, a historical figure. In her imagining, Mary is thrown out by her family at age 14 and falls into prostitution in London. Within a couple of years, she decides to reform her life by becoming a dressmaker’s assistant in her mother’s hometown of Monmouth, but her past won’t let her go. The close third person narration shifts to depict the constrained lives of the other women in the household: the mistress, Mrs Jones, who has lost multiple children and pregnancies; governess Mrs Ash, whose initial position as a wet nurse was her salvation after her husband left her; and Abi, an enslaved Black woman. This was gripping throughout, like a cross between Alias Grace and The Crimson Petal and the White. The only thing that had me on the back foot was that, it being Donoghue, I expected lesbianism. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)  Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as

Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer (1998): Only my second novel from Dyer, an annoyingly talented author who writes whatever he wants, in any genre, inimitably. This reminded me of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi for its hedonistic travels. Luke and Alex, twentysomething Englishmen, meet as factory workers in Paris and quickly become best mates. With their girlfriends, Nicole and Sahra, they form what seems an unbreakable quartet. The couples carouse, dance in nightclubs high on ecstasy, and have a lot of sex. A bit more memorable are their forays outside the city for Christmas and the summer. The first-person plural perspective resolves into a narrator who must have fantasized the other couple’s explicit sex scenes; occasional flash-forwards reveal that only one pair is destined to last. This is nostalgic for the heady days of youth in the same way as  Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

Sanctuary in the South: The Cats of Mas des Chats by Margaret Reinhold (1993): Reinhold (still alive at 96?!) is a South African psychotherapist who relocated from London to Provence, taking her two cats with her and eventually adopting another eight, many of whom had been neglected by owners in the vicinity. This sweet and meandering book of vignettes about her pets’ interactions and hierarchy is generally light in tone, but with the requisite sadness you get from reading about animals ageing, falling ill or meeting with accidents, and (in two cases) being buried on the property. “Les chats sont difficiles,” as a local shop owner observes to her. But would we cat lovers have it any other way? Reinhold often imagines what her cats would say to her. Like Doreen Tovey, whose books this closely resembles, she is as fascinated by human foibles as by feline antics. One extended sequence concerns her doomed attempts to hire a live-in caretaker for the cats. She never learned her lesson about putting a proper contract in place; several chancers tried the role and took advantage of her kindness. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

And the first two-thirds of Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts (1993): Thérèse and Léonie are cousins: the one French and the other English but making visits to her relatives in Normandy every summer. In the slightly forbidding family home, the adolescent girls learn about life, loss and sex. Each short chapter is named after a different object in the house. That Thérèse seems slightly otherworldly can be attributed to her inspiration, which Roberts reveals in a prefatory note: Saint Thérèse, aka The Little Flower. Roberts reminds me of A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay; her work is slightly austere and can be slow going, but her ideas always draw me in. (Secondhand – Newbury charity shop)

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?!

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?! My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them.

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them.

Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:  A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her.

A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her. Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Dear Fahrenheit 451

Dear Fahrenheit 451 I’ve been interested in

I’ve been interested in

For reading aloud with my husband, Ella prescribed one short story per evening sitting – a way for me to get through short story collections, which I sometimes struggle to finish, and a different way to engage with books. We also talked about the value of rereading childhood favorites such as Watership Down and Little Women, which I haven’t gone back to since I was nine and 12, respectively. In this anniversary year, Little Women would be the ideal book to reread (and the new television adaptation is pretty good too, Ella thinks).

For reading aloud with my husband, Ella prescribed one short story per evening sitting – a way for me to get through short story collections, which I sometimes struggle to finish, and a different way to engage with books. We also talked about the value of rereading childhood favorites such as Watership Down and Little Women, which I haven’t gone back to since I was nine and 12, respectively. In this anniversary year, Little Women would be the ideal book to reread (and the new television adaptation is pretty good too, Ella thinks). Various books came up over the course of our conversation: Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone [appearance in The Novel Cure: The Ten Best Novels to Cure the Xenophobic, but Ella brought it up because of the medical theme], Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume [cure: ageing, horror of], and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, a nonfiction guide to thinking creatively about your life, chiefly through 20-minute automatic writing exercises every morning. We agreed that it’s impossible to dismiss a whole genre, even if I do find myself weary of certain trends, like dystopian fiction (I introduced Ella to Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus, one of my favorite recent examples).

Various books came up over the course of our conversation: Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone [appearance in The Novel Cure: The Ten Best Novels to Cure the Xenophobic, but Ella brought it up because of the medical theme], Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume [cure: ageing, horror of], and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, a nonfiction guide to thinking creatively about your life, chiefly through 20-minute automatic writing exercises every morning. We agreed that it’s impossible to dismiss a whole genre, even if I do find myself weary of certain trends, like dystopian fiction (I introduced Ella to Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus, one of my favorite recent examples). I came away with two instant prescriptions: Heligoland by Shena Mackay [cure: moving house], about a shell-shaped island house that used to be the headquarters of a cult. It’s a perfect short book, Ella tells me, and will help dose my feelings of rootlessness after moving more than 10 times in the last 10 years. She also prescribed Family Matters by Rohinton Mistry [cure: ageing parents] and an eventual reread of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. As we discussed various other issues, such as my uncertainty about having children, Ella said she could think of 20 or more books to recommend me. “That’s a good thing, right?!” I asked.

I came away with two instant prescriptions: Heligoland by Shena Mackay [cure: moving house], about a shell-shaped island house that used to be the headquarters of a cult. It’s a perfect short book, Ella tells me, and will help dose my feelings of rootlessness after moving more than 10 times in the last 10 years. She also prescribed Family Matters by Rohinton Mistry [cure: ageing parents] and an eventual reread of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. As we discussed various other issues, such as my uncertainty about having children, Ella said she could think of 20 or more books to recommend me. “That’s a good thing, right?!” I asked.

As soon as I got back from London I ordered secondhand copies of Heligoland, Jitterbug Perfume and The Artist’s Way, and borrowed Family Matters from the public library the next day. Within a few days four further book prescriptions arrived for me by e-mail. Ella did say that her job is made harder when her clients read a lot, so kudos to her for prescribing books I’d not read – with the one exception of Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, which I love.

As soon as I got back from London I ordered secondhand copies of Heligoland, Jitterbug Perfume and The Artist’s Way, and borrowed Family Matters from the public library the next day. Within a few days four further book prescriptions arrived for me by e-mail. Ella did say that her job is made harder when her clients read a lot, so kudos to her for prescribing books I’d not read – with the one exception of Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, which I love.