Three on a Theme for Father’s Day: Holt Poetry, Filgate & Virago Anthologies

A rare second post in a day for me; I got behind with my planned cat book reviews. I happen to have had a couple of fatherhood-themed books come my way earlier this year, an essay anthology and a debut poetry collection. To make it a trio, I finished an anthology of autobiographical essays about father–daughter relationships that I’d started last year.

What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, ed. Michele Filgate (2025)

This follow-up to Michele Filgate’s What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About is an anthology of 16 compassionate, nuanced essays probing the intricacies of family relationships.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Some take the title brief literally: Heather Sellers dares to ask her father about his cross-dressing when she visits him in a nursing home; Nayomi Munaweera is pleased her 82-year-old father can escape his arranged marriage, but the domestic violence that went on in it remains unspoken. Tomás Q. Morín’s “Operation” has the most original structure, with the board game’s body parts serving as headings. All the essays display psychological insight, but Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s—contrasting their father’s once-controlling nature with his elderly vulnerability—is the pinnacle.

Despite the heavy topics—estrangement, illness, emotional detachment—these candid pieces thrill with their variety and their resonant themes. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness. (The above is my unedited version.)

Father’s Father’s Father by Dane Holt (2025)

Holt’s debut collection interrogates masculinity through poems about bodybuilders and professional wrestlers, teenage risk-taking and family misdemeanours.

Your father’s father’s father

poisoned a beautiful horse,

that’s the story. Now you know this

you’ve opened the door marked

‘Family History’.

(from “‘The Granaries are Bursting with Meal’”)

The only records found in my grandmother’s attic

were by scorned women for scorned women

written by men.

(from “Tammy Wynette”)

He writes in the wake of the deaths of his parents, which, as W.S. Merwin observed, makes one feel, “I could do anything,” – though here the poet concludes, “The answer can be nothing.” Stylistically, the collection is more various than cohesive, with some of the late poetry as absurdist as you find in Caroline Bird’s. My favourite poem is “Humphrey Bogart,” with its vision of male toughness reinforced by previous generations’ emotional repression:

My grandfather

never told his son that he loved him.

I said this to a group of strangers

and then said, Consider this:

his son never asked to be told.

They both loved

the men Humphrey Bogart played.

…

There was

one thing my grandfather could

not forgive his son for.

Eventually it was his son’s dying, yes.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen (1983; 1994)

“I doubt if my father will ever lose his power to wound me, and yet…”

~Eileen Fairweather

I read the introduction and first seven pieces (one of them a retelling of a fairy tale) last year and reviewed that first batch here. Some common elements I noted in those were service in a world war, Freudian interpretation, and the alignment of the father with God. The writers often depicted their fathers as unknown, aloof, or as disciplinarians. In the remainder of the book, I particularly noted differences in generations and class. Father and daughter are often separated by 40–55 years. The men work in industry; their daughters turn to academia. Her embrace of radicalism or feminism can alienate a man of conservative mores.

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

I mostly skipped over the quotes from novels and academic works printed between the essays. There are solid pieces by Adrienne Rich, Michèle Roberts, Sheila Rowbotham, and Alice Walker, but Alice Munro knocks all the other contributors into a cocked hat with “Working for a Living,” which is as detailed and psychologically incisive as one of her stories (cf. The Beggar Maid with its urban/rural class divide). Her parents owned a fox farm but, as it failed, her father took a job as night watchman at a factory. She didn’t realize, until one day when she went in person to deliver a message, that he was a janitor there as well.

This was a rewarding collection to read and I will keep it around for models of autobiographical writing, but it now feels like a period piece: the fact that so many of the fathers had lived through the world wars, I think, might account for their cold and withdrawn nature – they were damaged, times were tough, and they believed they had to be an authority figure. Things have changed, somewhat, as the Filgate anthology reflects, though father issues will no doubt always be with us. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop)

#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Literary Wives Club: The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham (1927)

As far as I know, this is the first play we’ve chosen for the club. While I’m a Maugham fan, I haven’t read him in a while and I’ve never explored his work for the theatre. The Constant Wife is a straightforward three-act play with one setting: a large parlour in the Middletons’ home in Harley Street, London. A true drawing room comedy, then, with very simple staging.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER}

Rumours are circulating that surgeon John Middleton has been having an affair with his wife Constance’s best friend, Marie-Louise. It’s news to Mrs. Culver and Martha, Constance’s mother and sister – but not to Constance herself. Mrs. Culver, the traditional voice of a previous generation, opines that men are wont to stray and so long as the wife doesn’t find out, what harm can it do? Women, on the other hand, are “naturally faithful creatures and we’re faithful because we have no particular inclination to be anything else,” she says.

Other characters enter in twos and threes for gossip and repartee and the occasional confrontation. Marie-Louise’s husband, Mortimer Durham, shows up fuming because he’s found John’s cigarette-case under her pillow and assumes it can only mean one thing. Constance is in the odd position of defending her husband’s and best friend’s honour, even though she knows full well that they’re guilty. With her white lies, she does them the kindness of keeping their indiscretion quiet – and gives herself the moral upper hand.

Constance is matter of fact about the fading of romance. She is grateful to have had a blissful first five years of marriage; how convenient that both she and John then fell out of love with each other at the same time. The decade since has been about practicalities. Thanks to John, she has a home, respectability, and fine belongings (also a child, only mentioned in passing); why give all that up? She’s still fond of John, anyway, and his infidelity has only bruised her vanity. However, she wants more from life, and a sheepish John is inclined to give her whatever she asks. So she agrees to join an acquaintance’s interior decorating business.

The early reappearance of her old flame Bernard Kersal, who is clearly still smitten with her, seeds her even more daring decision in the final act, set one year after the main events. Having earned £1400 of her own money, she has more than enough to cover a six-week holiday in Italy. She announces to John that she’s deposited the remainder in his account “for my year’s keep,” and slyly adds that she’ll be travelling with Bernard. This part turns out to be a bluff, but it’s her way of testing their new balance of power. “I’m not dependent on John. I’m economically independent, and therefore I claim my sexual independence,” she declares in her mother’s company.

There are some very funny moments in the play, such as when Constance tells her mother she’ll place a handkerchief on the piano as a secret sign during a conversation. Her mother then forgets what it signifies and Constance ends up pulling three hankies in a row from her handbag. I had to laugh at Mrs. Culver’s test for knowing whether you’re in love with someone: “Could you use his toothbrush?” It’s also amusing that Constance ends up being the one to break up with John for Marie-Louise, and with Marie-Louise for John.

However, there are also hidden depths of feeling meant to be brought out by the actors. At least three times in scenes between John and Constance, I noted the stage direction “Breaking down” in parentheses. The audience, therefore, is sometimes privy to the emotion that these characters can’t express to each other because of their sardonic wit and stiff upper lips.

I hardly ever experience plays, so this was interesting for a change. At only 70-some pages, it’s a quick read even if a bit old-fashioned or tedious in places. It does seem ahead of its time in questioning just what being true to a spouse might mean. A clever and iconoclastic comedy of manners, it’s a pleasant waystation between Oscar Wilde and Alan Ayckbourn.

(Free download from Internet Archive – is this legit or a copyright scam??) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Answered by means of quotes from Constance.

- Partnership is important, yes, but so is independence. (Money matters often crop up in the books we read for the club.)

“there is only one freedom that is really important, and that is economic freedom”

- Marriage often outlasts the initial spark of lust, and can survive one or both partners’ sexual peccadilloes. (Maugham, of course, was a closeted homosexual married to a woman.)

“I am tired of being the modern wife.” When her mother asks for clarification, she adds rather bluntly, “A prostitute who doesn’t deliver the goods.”

“I may be unfaithful, but I am constant. I always think that’s my most endearing quality.”

We have a new member joining us this month: Becky, from Australia, who blogs at Aidanvale. Welcome! Here’s the group’s page on Kay’s website.

See Becky’s, Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Novel about My Wife by Emily Perkins

May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

#1952Club: Patricia Highsmith, Paul Tillich & E.B. White

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I assembled an unlikely trio of lesbian romance, niche theology, and an animal-lover’s children’s classic.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this is widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (it’s more open-ended, really, but certainly not tragic; suicide was a common consequence in earlier fiction). Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer in New York City, takes a job selling dolls in a department store one Christmas season. Her boyfriend, Richard, is a painter and has promised to take her to Europe, but she’s lukewarm about him and the physical side of their relationship has never interested her. One day, a beautiful blonde woman in a fur coat – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – comes to her counter to order a doll and have it sent to her out in New Jersey. Therese sends a Christmas card to the same address, and the women start meeting up for drinks and meals.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

The second half of the book has Carol and Therese setting out on a road trip out West. It should be an idyllic consummation, but they realize they’re being trailed by a private detective collecting evidence for Carol’s husband Harge to use against her in a custody battle. I was reminded of the hunt for Humbert Humbert and his charge in Lolita; “the whole world was ready to be their enemy,” Therese realizes, and to consider their relationship “sordid and pathological,” as Richard describes it in a letter.

The novel is a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds against it. I’d read five of Highsmith’s mysteries and thought them serviceable but nothing special (I don’t read crime in general). This does, however, share their psychological intensity and the suspense about how things will play out. Highsmith gives details about Therese’s early life and Carol’s previous intimate friendship that help to explain some things but never reduce either character to a diagnosis or a tendency. Neither of them wanted just anyone, some woman; it was this specific combination of souls that sparked at first sight. (Secondhand from a charity shop that closed long ago, so I know I’d had it on my shelf unread since 2016!) ![]()

The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

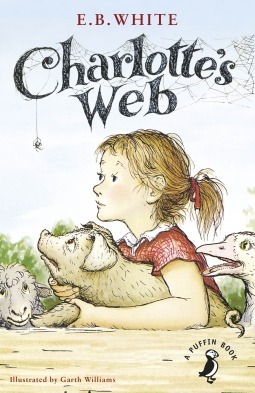

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

Charlotte is a fine specimen of a barn spider, well spoken and witty. She puts her mind to saving Wilbur’s bacon by weaving messages into her web, starting with “Some Pig.” He’s soon a county-wide spectacle, certain to survive the chop. But a farm is always, inevitably, a place of death. White fashions such memorable characters, including Templeton the gluttonous rat, and captures the hope of new life returning as the seasons turn over. Talking animals aren’t difficult to believe in when Fern can hear every word they say. The black-and-white line drawings are adorable. And making readers care about invertebrates? That’s a lasting achievement. I’m sure I read this several times as a child, but I appreciated it all the more as an adult. (Little Free Library) ![]()

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, and 1970 Club.

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

Last year I read the previous book,

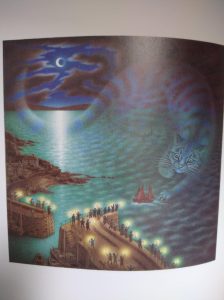

Last year I read the previous book,  The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

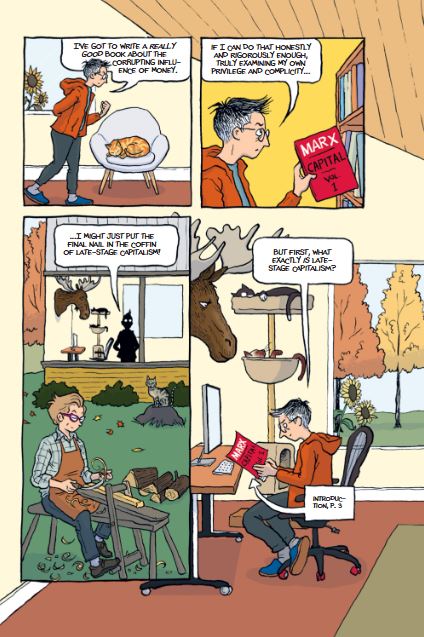

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

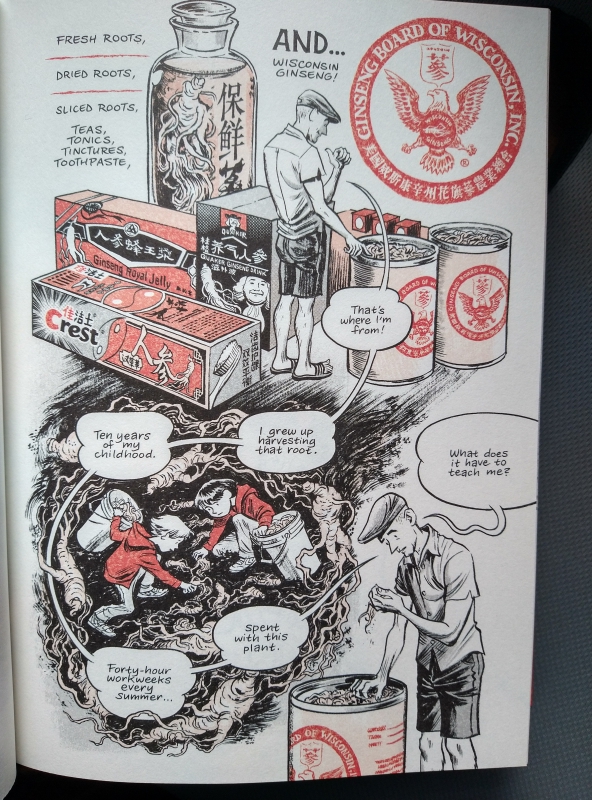

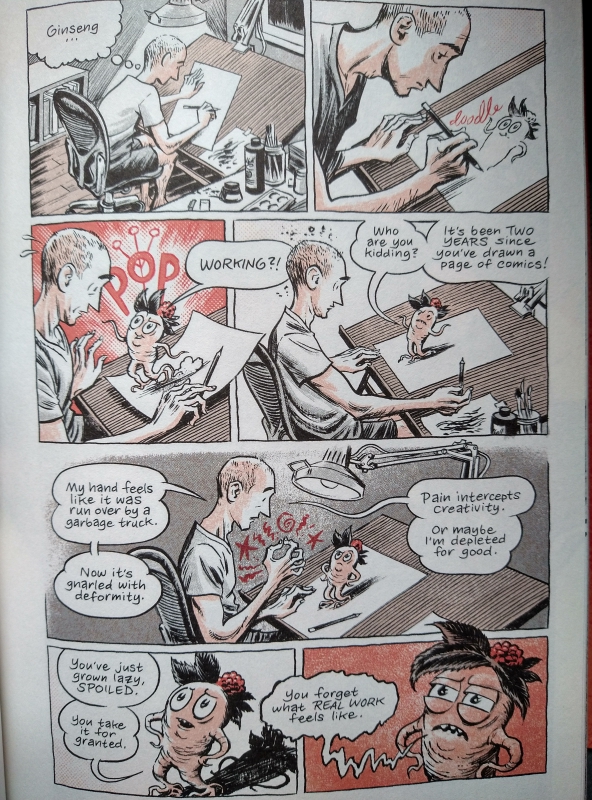

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,