Two Final Wellcome Book Prize Longlist Reviews: Krasnostein & Moshfegh

I’ve now read eight of the 12 titles longlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize 2019 and skimmed another two, leaving just two unexplored.

My latest two reads are books that I hugely enjoyed yet would be surprised to see make the shortlist (both  ):

):

The Trauma Cleaner: One Woman’s Extraordinary Life in Death, Decay and Disaster by Sarah Krasnostein (2017)

I guarantee you’ve never read a biography quite like this one. For one thing, its subject is still alive and has never been much of a public figure, at least not outside Victoria, Australia. For another, your average biography is robustly supported by archival evidence; to the contrary, this is a largely oral history conveyed by an unreliable narrator. And lastly, whether a biography is critical or adulatory overall, the author usually at least feigns objectivity. Sarah Krasnostein doesn’t bother with that. Sandra Pankhurst’s life is an incredible blend of ordinary and bizarre circumstances and experiences, and it’s clear Krasnostein is smitten with her. “I fall in love … anew each time I listen to her speak,” she gushes towards the book’s end. At first I was irked by all the fawning adjectives she uses for Sandra, but eventually I stopped noticing them and allowed myself to sink into this astonishing story.

I guarantee you’ve never read a biography quite like this one. For one thing, its subject is still alive and has never been much of a public figure, at least not outside Victoria, Australia. For another, your average biography is robustly supported by archival evidence; to the contrary, this is a largely oral history conveyed by an unreliable narrator. And lastly, whether a biography is critical or adulatory overall, the author usually at least feigns objectivity. Sarah Krasnostein doesn’t bother with that. Sandra Pankhurst’s life is an incredible blend of ordinary and bizarre circumstances and experiences, and it’s clear Krasnostein is smitten with her. “I fall in love … anew each time I listen to her speak,” she gushes towards the book’s end. At first I was irked by all the fawning adjectives she uses for Sandra, but eventually I stopped noticing them and allowed myself to sink into this astonishing story.

Sandra was born male and adopted by a couple whose child had died. When they later conceived again, they basically disowned ‘Peter’, moving him to an outdoor shed and making him scrounge for food. His adoptive father was an abusive alcoholic and kicked him out permanently when he was 17. Peter married ‘Linda’ at age 19 and they had two sons in quick succession, but he was already going to gay bars and wearing makeup; when he heard about the possibility of a sex change, he started taking hormones right away. Even before surgery completed the gender reassignment, Sandra got involved in sex work, and was a prostitute for years until a brutal rape at the Dream Palace brothel drove her to seek other employment. Cleaning and funeral home jobs nicely predicted the specialty business she would start after the hardware store she ran with her late husband George went under: trauma cleaning.

Krasnostein parcels this chronology into tantalizing pieces, interspersed with chapters in which she accompanies Sandra and her team on assignments. They fumigate and clean up bodily fluids after suicides and overdoses, but also deal with clients who have lost control of their possessions – and, to some extent, their lives. They’re hoarders, cancer patients and ex-convicts; their homes are overtaken by stuff and often saturated with mold or feces. Sandra sympathizes with the mental health struggles that lead people into such extreme situations. Her line of work takes “Great compassion, great dignity and a good sense of humour,” she tells Krasnostein; even better if you can “not … take the smell in, ’cause they stink.”

Krasnostein parcels this chronology into tantalizing pieces, interspersed with chapters in which she accompanies Sandra and her team on assignments. They fumigate and clean up bodily fluids after suicides and overdoses, but also deal with clients who have lost control of their possessions – and, to some extent, their lives. They’re hoarders, cancer patients and ex-convicts; their homes are overtaken by stuff and often saturated with mold or feces. Sandra sympathizes with the mental health struggles that lead people into such extreme situations. Her line of work takes “Great compassion, great dignity and a good sense of humour,” she tells Krasnostein; even better if you can “not … take the smell in, ’cause they stink.”

The author does a nice job of staying out of the narrative: though she’s an observer and questioner, there’s only the occasional paragraph in which she mentions her own life. Her mother left when she was young, which helps to explain why she is so compassionate towards the addicts and hoarders she meets with Sandra. Some of the loveliest passages have her pondering how things got so bad for these people and affirming that their lives still have value. As for Sandra herself – now in her sixties and increasingly ill with lung disease and cirrhosis – Krasnostein believes she’s never been unconditionally loved and so has never formed true human connections.

The author does a nice job of staying out of the narrative: though she’s an observer and questioner, there’s only the occasional paragraph in which she mentions her own life. Her mother left when she was young, which helps to explain why she is so compassionate towards the addicts and hoarders she meets with Sandra. Some of the loveliest passages have her pondering how things got so bad for these people and affirming that their lives still have value. As for Sandra herself – now in her sixties and increasingly ill with lung disease and cirrhosis – Krasnostein believes she’s never been unconditionally loved and so has never formed true human connections.

This book does many different things in its 250 pages. It’s part journalistic exposé and part “love letter”; it’s part true crime and part ordinary life story. It considers gender, mental health, addiction, trauma and death. It’s also simply a terrific read that should draw in lots of people who wouldn’t normally pick up nonfiction. I don’t expect it to advance to the shortlist, but if it does I’ll be not-so-secretly delighted.

A favorite passage:

Sometimes, listening to Sandra try to remember the events of her life is like watching someone reel in rubbish on a fishing line: a weird mix of surprise, perplexity and unexpected recognition. No matter how many times we go over the first three decades of her life, the timeline of places and dates is never clear. Many of her memories have a quality beyond being merely faded; they are so rusted that they have crumbled back into the soil of her origins. Others have been fossilised, frozen in time, and don’t have a personal pull until they defrost slightly in the sunlit air between us as we speak. And when that happens there is a tremor in her voice as she integrates them back into herself, not seamlessly but fully.

See also:

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (2018)

If you’ve read her Booker-shortlisted debut, Eileen, you’ll be unsurprised to hear that Moshfegh has written another love-it-or-hate-it book with a narrator whose odd behavior is hard to stomach. This worked better for me than Eileen, I think because I approached it as a deadpan black comedy in the same vein as Elif Batuman’s The Idiot. Its inclusion on the Wellcome longlist is somewhat tenuous: in 2000 the unnamed narrator, in her mid-twenties, gets a negligent psychiatrist to prescribe her drugs for insomnia and depression and stockpiles them so she can take pill cocktails to knock herself out for days at a time. In a sense this is a way of extending the numbness that started with her parents’ deaths – her father from cancer and her mother by suicide. But there’s also a more fantastical scheme in her mind: “when I’d slept enough, I’d be okay, I’d be renewed, reborn. I would be a whole new person.”

Ever since she was let go from her job at a gallery that showcases ridiculous modern art, the only people in this character’s life are an on-again, off-again boyfriend, Trevor, and her best (only) friend from college, longsuffering Reva, who keeps checking up on her in her New York City apartment even though she consistently treats Reva with indifference or disdain. Soon her life is a bleary cycle of sleepwalking and sleep-shopping, interspersed with brief periods of wakefulness, during which she watches a nostalgia-inducing stream of late-1990s movies on video (the kind of stuff I watched at sleepovers with my best friend during high school) – she has a weird obsession with Whoopi Goldberg.

Ever since she was let go from her job at a gallery that showcases ridiculous modern art, the only people in this character’s life are an on-again, off-again boyfriend, Trevor, and her best (only) friend from college, longsuffering Reva, who keeps checking up on her in her New York City apartment even though she consistently treats Reva with indifference or disdain. Soon her life is a bleary cycle of sleepwalking and sleep-shopping, interspersed with brief periods of wakefulness, during which she watches a nostalgia-inducing stream of late-1990s movies on video (the kind of stuff I watched at sleepovers with my best friend during high school) – she has a weird obsession with Whoopi Goldberg.

It’s a wonder the plot doesn’t become more repetitive. I like reading about routines, so I was fascinated to see how the narrator methodically takes her project to extremes. Amazingly, towards the middle of the novel she gets herself from a blackout situation to Reva’s mother’s funeral – about the only time we see somewhere that isn’t her apartment, the corner shop, the pharmacy or Dr. Tuttle’s office – and this interlude is just enough to break things up. There are lots of outrageous lines and preposterous decisions that made me laugh. Consumerism and self-medication to deaden painful emotions are the targets of this biting satire. As 9/11 approaches, you wonder what it will take to wake this character up to her life. I’ve often wished I could hibernate through British winters, but I wouldn’t do what Moshfegh’s antiheroine does. Call this a timely cautionary tale about privilege and disengagement.

Favorite lines:

“Initially, I just wanted some downers to drown out my thoughts and judgments, since the constant barrage made it hard not to hate everyone and everything. I thought life would be more tolerable if my brain were slower to condemn the world around me.”

“Oh, sleep, nothing else could ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.”

Reva: “you’re not changing anything in your sleep. You’re just avoiding your problems. … Your problem is that you’re passive. You wait around for things to change, and they never will. That must be a painful way to live. Very disempowering.”

See also:

And one more that I got out from the library and skimmed:

Murmur by Will Eaves (2018)

The subject is Alec Pryor, or “the scientist.” It’s clear that he is a stand-in for Alan Turing, quotes from whom appear as epigraphs at the head of most chapters. Turing was arrested for homosexuality and subjected to chemical castration. I happily read the first-person “Part One: Journal,” which was originally a stand-alone story (shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award 2017), but “Part Two: Letters and Dreams” was a lot harder to get into, so I ended up just giving the rest of the book a quick skim. If this is shortlisted, I promise to return to it and give it fair consideration.

The subject is Alec Pryor, or “the scientist.” It’s clear that he is a stand-in for Alan Turing, quotes from whom appear as epigraphs at the head of most chapters. Turing was arrested for homosexuality and subjected to chemical castration. I happily read the first-person “Part One: Journal,” which was originally a stand-alone story (shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award 2017), but “Part Two: Letters and Dreams” was a lot harder to get into, so I ended up just giving the rest of the book a quick skim. If this is shortlisted, I promise to return to it and give it fair consideration.

See also:

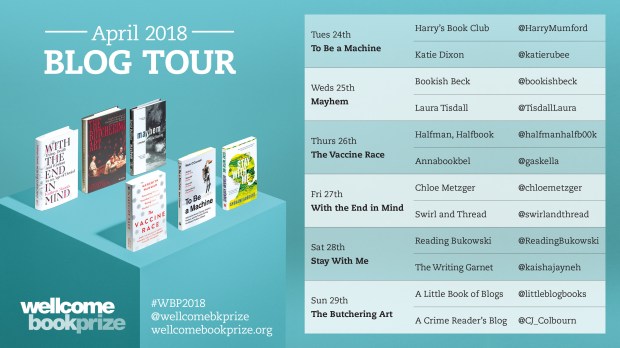

We will announce our shadow panel shortlist on Friday. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews, predictions and reactions.

Heartland by Sarah Smarsh

If you were a fan of Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance, then debut author Sarah Smarsh’s memoir, Heartland, deserves to be on your radar too. Smarsh comes from five generations of Kansas wheat farmers and worked hard to step outside of the vicious cycle that held back the women on her mother’s side of the family: poverty, teen pregnancy, domestic violence, broken marriages, a lack of job security, and moving all the time. Like Mamaw in Vance’s book, Grandma Betty is the star of the show here: a source of pure love, she played a major role in raising Smarsh. The rundown of Betty’s life is sobering: her father was abusive and her mother had schizophrenia; she got pregnant at 16; and she racked up six divorces and countless addresses. This passage about her paycheck and diet jumped out at me:

Each month, after she paid the rent and utilities, and the landlady for watching Jeannie, Betty had $27 left. She budgeted some of it for cigarettes and gas. The rest went to groceries from the little store around the corner. The store sold frozen pot pies, five for a dollar. She’d buy twenty-five of them, beef and chicken flavor, and that would be her dinner all month. Every day, a candy bar for lunch at work and a frozen pot pie for dinner at home.

It’s a sad state of affairs when fatty processed foods are cheaper than healthy ones, and this is still the case today: the underprivileged are more likely to subsist on McDonald’s than on vegetables. Heartland is full of these kinds of contradictions. For instance, in the Reagan years the country shifted rightwards and working-class Catholics like Smarsh’s mother started voting Republican – in contravention of the traditional understanding that the Democrats were for the poor and the Republicans were for the rich. Smarsh followed her mother’s lead by casting her first-ever vote for George W. Bush in 2000, but her views changed in college when she learned how conservative fiscal policies keep people poor.

This isn’t a straightforward, chronological family story; it jumps through time and between characters. You might think of reading it as like joining Smarsh for an amble around the farm or a flip through a photograph album. Its vignettes are vivid, if sometimes hard to join into a cohesive story line in the mind. Some of the scenes that stood out to me were being pulled by truck through the snow on a canoe, helping Grandma Betty move into a house in Wichita but high-tailing it out of there when they realized it was infested by cockroaches, and the irony of winning a speech contest about drug addiction when her stepmother was hooked on opioids.

This isn’t a straightforward, chronological family story; it jumps through time and between characters. You might think of reading it as like joining Smarsh for an amble around the farm or a flip through a photograph album. Its vignettes are vivid, if sometimes hard to join into a cohesive story line in the mind. Some of the scenes that stood out to me were being pulled by truck through the snow on a canoe, helping Grandma Betty move into a house in Wichita but high-tailing it out of there when they realized it was infested by cockroaches, and the irony of winning a speech contest about drug addiction when her stepmother was hooked on opioids.

Heartland serves as a personal tour through some of the persistent trials of working-class life in the American Midwest: urbanization and the death of the family farm, an inability to afford health insurance and the threat of toxins encountered in the workplace, and the elusive dream of home ownership. Like Vance, Smarsh has escaped most of the worst possibilities through determination and education, so is able to bring an outsider’s clarity to the issues. At times she has a tendency to harp on the same points, though, adding in generalizations about the effects of poverty rather than just letting her family’s stories speak for themselves.

The oddest thing about Smarsh’s memoir – and I am certainly not the first reviewer to mention this since the book’s U.S. release in September – is who it’s directed to: her never-to-be-born daughter, “August”. Teen pregnancy was the family curse Smarsh was most desperate to avoid, and even now that she’s in her late thirties, a journalist and academic returned to Kansas after years on the East Coast, she remains childless. August is who Smarsh had in mind while working two or more jobs all through high school, earning higher degrees and buying her dream home. All along she was saving August from the hardships of a poor upbringing. While the unborn child is a potent symbol, it can be disorienting after pages of “I” to come across a “you” and have to readjust to who is being addressed.

Heartland is a striking book, not without its challenges to the reader, but one that I ultimately found rewarding to read in short bursts of 10 to 20 pages at a time. It’s worthwhile for anyone interested in what it’s really like to be poor in America.

My rating:

A favorite passage:

“My life has been a bridge between two places: the working poor and ‘higher’ economic classes. The city and the country. College-educated coworkers and disenfranchised loved ones. A somewhat conservative upbringing and a liberal adulthood. Home in the middle of the country and work on the East Coast. The physical world where I talk to people and the formless dimension where I talk to you.”

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth was published by Scribe UK on November 8th. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

4 Reasons to Love Julie Buntin’s Debut Novel, Marlena

I managed to miss Marlena when it first came out last year; luckily, I had another chance at reading it when it was released in paperback a couple of months ago. It bears some thematic similarities to Emma Cline’s The Girls, Rosalie Knecht’s Relief Map, Andrée Michaud’s The Last Summer, Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones and especially Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves, but Marlena is a cut above. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Occasionally I weary of writing straightforward reviews – let’s be honest, you get tired of reading them, too – so I’m returning to a format I last used for my review of The Animators and pulling out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

I managed to miss Marlena when it first came out last year; luckily, I had another chance at reading it when it was released in paperback a couple of months ago. It bears some thematic similarities to Emma Cline’s The Girls, Rosalie Knecht’s Relief Map, Andrée Michaud’s The Last Summer, Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones and especially Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves, but Marlena is a cut above. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Occasionally I weary of writing straightforward reviews – let’s be honest, you get tired of reading them, too – so I’m returning to a format I last used for my review of The Animators and pulling out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

- Michigan. Have you ever read another book set in northern Michigan? After her parents’ divorce, Cat moves to Silver Lake with her mom and older brother, and almost immediately meets Marlena Joyner, their new next-door neighbor. Although Marlena drowns in suspicious circumstances less than a year later – this is not a spoiler; it is part of the back cover blurb and is also revealed on the fourth page – her impact on Cat will last for decades. The setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom.

Probably most teenagers think where they live is boring. But there aren’t words for the catastrophic dreariness of being fifteen in northern Michigan at the tail end of winter, when you haven’t seen the sun in weeks and the snow won’t stop coming and there’s nowhere to go and you’re always cold and everyone you know is broke…

- Emulation and Envy. Catherine wants to be just like 17-year-old Marlena: experienced, sensual and insouciant. She puts childish hobbies and studious habits behind her and remakes herself as “Cat” at her new school. Through Marlena she develops a taste for alcohol and cigarettes. She also turns truant and starts hanging out with drug dealers at all hours. All along she’s conveniently ignoring that Marlena is essentially parentless – her mother left and her father cooks meth – and that popping pills and sleeping around aren’t exactly a great strategy for getting out of Silver Lake. Living with a single mom who works as a cleaner, Cat also starts to envy the rich incomers whose summer houses she helps to clean. In the scene that may well linger with me the longest, Cat tastes whole almonds for the first time at the Hodsons’ mansion and steals a stash.

I looked up to Marlena—she was tough and beautiful and I never once thought she wasn’t in control. … Even at fifteen I wasn’t dumb enough to glamorize Marlena’s world, the poverty, the drugs that were the fabric of everything, but I was attracted to it all the same.

- Teenage Shenanigans. I was the squeakiest of squeaky clean kids in high school, but it’s always fun to experience very different lives through fiction. With Cat and Marlena you’ll get to skip school, throw unsupervised parties, and pull all manner of pranks. Their most impressive spectacle is affixing giant papier-mâché genitalia to a Big Boy restaurant statue as an act of revenge on a teacher who hit on Marlena.

Everything was happening in consequence-less free fall … the two of us made one perfect, unfuckwithable girl. Nothing could hurt us, as long as we weren’t alone.

- Hindsight Is Everything. Cat is writing this nearly 20 years later. In short interludes labeled “New York,” we learn about her adult life: a job in a library, a husband named Liam, and an ongoing struggle with a bad habit she formed under Marlena’s influence. When Marlena’s little brother Sal gets in touch and asks to visit Cat in New York City to hear about the sister he barely remembers, it sparks a trip back into memory. This narrative is like an exorcism or a system detox for Cat: not until she gets it out can she truly live her own life.

Those days were so big and electric that they swallowed the future and the past … a difficulty letting go of the past can run in families, like a problematic thyroid.

This is one of those books where the narration is so utterly convincing that you don’t so much read the plot as live it out. I felt no distance between Cat and me. When a first-person voice is this successful, you wonder why an author would ever choose anything else.

My rating:

Marlena was published in paperback in the UK by Picador on April 19th. My thanks to the publisher for sending a free copy for review.

Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist Event

Five of the six shortlisted authors (barring Dublin-based Mark O’Connell) were at the Wellcome Collection in London yesterday to share more about their books in mini-interviews with Lisa O’Kelly, the associate editor of the Observer. She called each author up onto the stage in turn for a five-minute chat about her work, and then brought them all up for a general conversation and audience questions. Clare and I found it a very interesting afternoon. Here’s some context that I gleaned about the five books and their writers.

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Sigrid Rausing started writing her book soon after her sister-in-law Eva’s body was found: just random paragraphs to make sense of what had happened. From there it became an investigation, a quest to find the nature of addiction. She thinks that as a society we still don’t quite understand what addiction is, and the medical research and public perception are very separate. In addition to nature and nurture, she thinks we should consider the influence of culture – as an anthropologist by training, she’s very interested in drug culture and how that drew in her brother, Hans. Although there have been many memoirs by ex-addicts, she can’t think of another one by a family member. Perhaps, she suggested, this is because the addict is seen as the ultimate victim. She referred to her book as a “collage,” a very apt description.

Kathryn Mannix spoke of how her grandmother, born in 1900, saw so much more death than we do nowadays: siblings, a child, and so on. Today, though, Mannix has encountered people in their sixties who are facing, with their parents, their very first deaths. Death is fairly “gentle” and “dull” if you’re not directly involved, she insists; she blames Hollywood and Eastenders for showing unusually dramatic deaths. She said once you understand what exactly people are afraid of about dying (e.g. hell, oblivion, pain, leaving their families behind) you can address their specific concerns and thereby “beat out the demon of terror and fear.” Mannix never intended to write a book, but someone heard her on the radio and invited her to do so. Luckily, from her medical school days onward, she’d been writing an A4 page about each of her most mind-boggling cases to get them out of her head and move on. That’s why, as O’Kelly put it, the characters in her 30 stories “leap off the page.”

Mannix, Adebayo, O’Kelly, Rausing, Wadman & Fitzharris

Lindsey Fitzharris called The Butchering Art “a love story between science and medicine” – it was the first time that the former (antisepsis) was applied to the latter. She initially thought Robert Liston was her man – he was so colorful, larger than life – but eventually found that the real story was with Joseph Lister, the quiet, persistent Quaker. (However, the book does open with Liston performing the first surgery under ether.) Fitzharris is also involved in the Order of the Good Death, author Caitlin Doughty’s initiative, and affirmed Mannix’s efforts to remove the taboo from talking about death. I think I heard correctly that she said there is a film of The Butchering Art in the works?! I’ll need to look into that some more.

Meredith Wadman started with a brief explanation of how immunization works and why the 1960s were ripe for vaccine research. This segment went really science-y, which I thought was a little unfortunate as it may have made listeners tune out and be less interested in her work than the others’. It was perhaps inevitable given her subject matter, but also a matter of the questions O’Kelly asked – with the others she focused more on stories and themes than on scientific facts. It was interesting to hear what Wadman has been working on recently: for the past 6–8 months, she’s been reporting for Science on sexual harassment in science. For her next book, though, she’s pondering the conflict between a congressman and a Centers for Disease Control scientist over funding into research that might lead to gun control.

The question time brought up the issues of medical misinformation online, the distrust people with chronic illnesses have of medical professionals, and euthanasia – Mannix rather dodged that one, stating that her book is about the natural dying process so that’s not really her area. (Though it does come up in a chapter of her book.) We also heard a bit about the projects up next for each author. Rausing’s next book will be a travel memoir about the Capetown drought, taking in apartheid and her husband’s family’s immigration. Adebayo is at work on a very nebulous novel “about people,” and possibly how privilege affects access to healthcare.

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel Decision

Addiction, death, infertility, surgery, transhumanism and vaccines: It’s been quite the varied reading list for the five of us this spring! Lots of science, lots of medicine, but also a lot of stories and imagination.

After some conferring and voting, we have arrived at our shadow panel winner for the Wellcome Book Prize 2018: To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell.

Rarely have I been so surprised to love a book. It’s a delight to read, and no matter what your background or beliefs are, it will give you plenty to think about. It goes deep down, beneath our health and ultimately our mortality, to ask what the essence of being human is.

Here’s what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about our pick:

Annabel: “O’Connell, as a journalist and outsider in the surprisingly diverse field of transhumanism, treats everyone with respect: asking the questions, but not judging, to get to the heart of the transhumanists’ beliefs. For a subject based in technology, To Be a Machine is a profoundly human story.”

Clare: “The concept of transhumanism may not be widely known or understood yet, but O’Connell’s engaging and fascinating book explains the significance of the movement and its possible implications both in the distant future and how we live now.”

Laura: “My brain feels like it’s been wired slightly differently since reading To Be a Machine. It’s not just about weird science and weird scientists, but how we come to terms with the fact that even the luckiest of us live lives that are so brief.”

Paul: “An interesting book that hopefully will provoke further discussion as we embrace technology and it envelops us.”

On Monday we’ll find out which book the official judges have chosen. I could see three or four of these as potential winners, so it’s very hard to say who will take home the £30,000.

Who are you rooting for?

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Sigrid Rausing’s Mayhem

“Now that it’s all over I find myself thinking about family history and family memories; the stories that hold a family together and the acts that can split it apart.”

Sigrid Rausing’s brother, Hans, and his wife, Eva, were wealthy philanthropists – and drug addicts who kept it together long enough to marry and have children before relapsing. Hans survived that decade-long dive back into addiction, but Eva did not: in July 2012 the 48-year-old’s decomposed body was found in a sealed-off area of the couple’s £70 million Chelsea mansion. The postmortem revealed that she had been using cocaine, which threw her already damaged heart into a chaotic rhythm. She’d been dead in their drug den for over two months.

Those are the bare facts. Scandalous enough for you? But Mayhem is no true crime tell-all. It does incorporate the straightforward information that is in the public record – headlines, statements and appearances – but blends them into a fragmentary, dreamlike family memoir that proceeds through free association and obsessively deliberates about the nature and nurture aspects of addictive personalities. “We didn’t understand that every addiction case is the same dismal story,” she writes, in a reversal of Tolstoy’s maxim about unhappy families.

Rausing’s memories of idyllic childhood summers in Sweden reminded me of Tove Jansson stories, and the incessant self-questioning of a family member wracked by remorse is similar to what I’ve encountered in memoirs and novels about suicide in the family, such as Jill Bialosky’s History of a Suicide and Miriam Toews’ All My Puny Sorrows. Despite all the pleading letters and e-mails she sent Hans and Eva, and all the interventions and rehab spells she helped arrange, Rausing has a nagging “sense that when I tried I didn’t try hard enough.”

The book moves sinuously between past and present, before and after, fact and supposition. There are a lot of peculiar details and connections in this story, starting with the family history of dementia and alcoholism. Rausing’s grandfather founded the Tetra Pak packaging company, later run by her father. Eva had a pet conspiracy theory that her father-in-law murdered Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986.

Rausing did anthropology fieldwork in Estonia and is now the publisher of Granta Books and Granta magazine. True to her career in editing, she’s treated this book project like a wild saga that had to be tamed, “all the sad and sordid details redacted,” but “I fear I have redacted too much,” she admits towards the end. She’s constantly pushing back against the more sensational aspects of this story, seeking instead to ground it in family experience. The book’s sketchy nature is in a sense necessary because information about her four nieces and nephews, of whom she took custody in 2007, cannot legally be revealed. But if she’d waited until they were all of age, might this have been a rather different memoir?

Mayhem effectively conveys the regret and guilt that plague families of addicts. It invites you to feel what it is really like to live through the “years of failed hope” that characterize this type of family tragedy. It doesn’t offer any easy lessons seen in hindsight. That makes it an uncomfortable read, but an honest one.

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

My gut feeling: This book’s style could put off more readers than it attracts. I can think of two other memoirs from the longlist that I would have preferred to see in this spot. I suppose I see why the judges rate Mayhem so highly – Edmund de Waal, the chair of this year’s judging panel, describes the Wellcome shortlist as “books that start debates or deepen them, that move us profoundly, surprise and delight and perplex us” – but it’s not in my top tier.

See what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about this book:

Annabel’s review: “Rausing is clearly a perceptive writer. She is very hard on herself; she is brutally honest, knowing that others will be hurt by the book.”

Clare’s review: “Rausing writes thoughtfully about the nature of addiction and its many contradictions.”

Laura’s review: “One of the saddest bits of Mayhem is when Rausing simply lists some of the press headlines that deal with her family story in reverse order, illustrating the seemingly inescapable spiral of addiction.”

Paul’s review: “It is not an easy read subject wise, thankfully Rausing’s sparse but beautiful writing helps makes this an essential read.”

Also, be sure to visit Laura’s blog today for an exclusive extract from Mayhem.

Shortlist strategy: Tomorrow I’ll post a quick response to Meredith Wadman’s The Vaccine Race.

If you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to one of the shortlist events being held this Saturday and Sunday.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and extracts have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.)

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale – Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of bipolar Cornwall artist Rachel Kelly and her interactions with her husband and four children, all of whom are desperate to earn her love. Quakerism, with its emphasis on silence and the inner light in everyone, sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows for family secrets to proliferate. There are two cameo appearances by an intimidating Dame Barbara Hepworth, and three wonderfully horrible scenes in which Rachel gives a child a birthday outing. The novel questions patterns of inheritance (e.g. of talent and mental illness) and whether happiness is possible in such a mixed-up family. (Our joint highest book club rating ever, with Red Dust Road. We all said we’d read more by Gale.) Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil – An extended essay whose overarching theme of hospitality stretches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to a culture of culinary abundance. Greed, especially for food, feels like her natural state, she acknowledges. However, living in Berlin has given her a greater awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU, often to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikhism she grew up in teaches unconditional kindness to strangers. She asks herself, and readers, how to cultivate the spirit of generosity. Clearly written and thought-provoking. (And typeset in Mrs Eaves, one of my favorite fonts.) See also  Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right.

Frost by Holly Webb – Part of a winter animals series by a prolific children’s author, this combines historical fiction and fantasy in an utterly charming way. Cassie is a middle child who always feels left out of her big brother’s games, but befriending a fox cub who lives on scrubby ground near her London flat gives her a chance for adventures of her own. One winter night, Frost the fox leads Cassie down the road – and back in time to the Frost Fair of 1683 on the frozen Thames. I rarely read middle-grade fiction, but this was worth making an exception for. It’s probably intended for ages eight to 12, yet I enjoyed it at 36. My library copy smelled like strawberry lip gloss, which was somehow just right. The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be.

The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame – This is the last and least enjoyable volume of Frame’s autobiography, but as a whole the trilogy is an impressive achievement. Never dwelling on unnecessary details, she conveys the essence of what it is to be (Book 1) a child, (2) a ‘mad’ person, and (3) a writer. After years in mental hospitals for presumed schizophrenia, Frame was awarded a travel fellowship to London and Ibiza. Her seven years away from New Zealand were a prolific period as, with the exception of breaks to go to films and galleries, and one obsessive relationship that nearly led to pregnancy out of wedlock, she did little else besides write. The title is her term for the imagination, which leads us to see Plato’s ideals of what might be. The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong.

The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins – Collins won the first novel category of the Costa Awards for this story of a black maid on trial in 1826 London for the murder of her employers, the Benhams. Margaret Atwood hit the nail on the head in a tweet describing the book as “Wide Sargasso Sea meets Beloved meets Alias Grace” (she’s such a legend she can get away with being self-referential). Back in Jamaica, Frances was a house slave and learned to read and write. This enabled her to assist Langton in recording his observations of Negro anatomy. Amateur medical experimentation and opium addiction were subplots that captivated me more than Frannie’s affair with Marguerite Benham and even the question of her guilt. However, time and place are conveyed convincingly, and the voice is strong. Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.”

Lost in Translation by Charlie Croker – This has had us in tears of laughter. It lists examples of English being misused abroad, e.g. on signs, instructions and product marketing. China and Japan are the worst repeat offenders, but there are hilarious examples from around the world. Croker has divided the book into thematic chapters, so the weird translated phrases and downright gobbledygook are grouped around topics like food, hotels and medical advice. A lot of times you can see why mistakes came about, through the choice of almost-but-not-quite-right synonyms or literal interpretation of a saying, but sometimes the mind boggles. Two favorites: (in an Austrian hotel) “Not to perambulate the corridors in the hours of repose in the boots of ascension” and (on a menu in Macao) “Utmost of chicken fried in bother.” All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning.

All the Water in the World by Karen Raney – Like The Fault in Our Stars (though not YA), this is about a teen with cancer. Sixteen-year-old Maddy is eager for everything life has to offer, so we see her having her first relationship – with Jack, her co-conspirator on an animation project to be used in an environmental protest – and contacting Antonio, the father she never met. Sections alternate narration between her and her mother, Eve. I loved the suburban D.C. setting and the e-mails between Maddy and Antonio. Maddy’s voice is sweet yet sharp, and, given that the main story is set in 2011, the environmentalism theme seems to anticipate last year’s flowering of youth participation. However, about halfway through there’s a ‘big reveal’ that fell flat for me because I’d guessed it from the beginning. Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle – I love these simple cartoons about aliens and the sense they manage to make of Earth and its rituals. The humor mostly rests in their clinical synonyms for everyday objects and activities (parenting, exercise, emotions, birthdays, office life, etc.). Pyle definitely had fun with a thesaurus while putting these together. It’s also about gentle mockery of the things we think of as normal: consider them from one remove, and they can be awfully strange. My favorites are still about the cat. You can also see his work on

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife.

Bedtime Stories for Worried Liberals by Stuart Heritage – I bought this for my husband purely for the title, which couldn’t be more apt for him. The stories, a mix of adapted fairy tales and new setups, are mostly up-to-the-minute takes on US and UK politics, along with some digs at contemporary hipster culture and social media obsession. Heritage quite cleverly imitates the manner of speaking of both Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. By its nature, though, the book will only work for those who know the context (so I can’t see it succeeding outside the UK) and will have a short shelf life as the situations it mocks will eventually fade into collective memory. So, amusing but not built to last. I particularly liked “The Night Before Brexmas” and its all-too-recognizable picture of intergenerational strife. My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”).

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite – The Booker Prize longlist and the Women’s Prize shortlist? You must be kidding me! The plot is enjoyable enough: a Nigerian nurse named Korede finds herself complicit in covering up her gorgeous little sister Ayoola’s crimes – her boyfriends just seem to end up dead somehow; what a shame! – but things get complicated when Ayoola starts dating the doctor Korede has a crush on and the comatose patient to whom Korede had been pouring out her troubles wakes up. My issue was mostly with the jejune writing, which falls somewhere between high school literary magazine and television soap (e.g. “My hands are cold, so I rub them on my jeans” & “I have found that the best way to take your mind off something is to binge-watch TV shows”). On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)

On Love and Barley – Haiku of Basho [trans. from the Japanese by Lucien Stryk] – These hardly work in translation. Almost every poem requires a contextual note on Japan’s geography, flora and fauna, or traditions; as these were collected at the end but there were no footnote symbols, I didn’t know to look for them, so by the time I read them it was too late. However, here are two that resonated, with messages about Zen Buddhism and depression, respectively: “Skylark on moor – / sweet song / of non-attachment.” (#83) and “Muddy sake, black rice – sick of the cherry / sick of the world.” (#221; reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s “tired of London, tired of life” maxim). My favorite, for personal relevance, was “Now cat’s done / mewing, bedroom’s / touched by moonlight.” (#24)

The resulting memoir is a somber, meditative book that doesn’t gloss over the difficulties of queer family-making, but also sees some potential advantages: to an extent, one has the privilege of choice – he and Andrew specified that they couldn’t raise a child with severe disabilities or trauma, but were fine with one of any race – whereas biological parents don’t really have any idea of what they’re going to get. However, same-sex couples are plagued by bureaucracy and, yes, prejudice still. Nothing comes easy. They have to fill out a 50-page questionnaire about their concerns and what they have to offer a child. A social worker humiliates them by forcing them to do a dance-off video game to prove that a pair of introverted, cultured academics can have fun, too.

The resulting memoir is a somber, meditative book that doesn’t gloss over the difficulties of queer family-making, but also sees some potential advantages: to an extent, one has the privilege of choice – he and Andrew specified that they couldn’t raise a child with severe disabilities or trauma, but were fine with one of any race – whereas biological parents don’t really have any idea of what they’re going to get. However, same-sex couples are plagued by bureaucracy and, yes, prejudice still. Nothing comes easy. They have to fill out a 50-page questionnaire about their concerns and what they have to offer a child. A social worker humiliates them by forcing them to do a dance-off video game to prove that a pair of introverted, cultured academics can have fun, too.

The book’s epistolary style deftly combines fragments of various document types: James’s biography-in-progress and an oral history he’s assembled from conversations with those who knew Maas, his narrative of his quest, transcripts of interviews and phone conversations, e-mails and more. All of this has been brought together into manuscript form by an anonymous editor whose presence is indicated through coy but increasingly tiresome long footnotes.

The book’s epistolary style deftly combines fragments of various document types: James’s biography-in-progress and an oral history he’s assembled from conversations with those who knew Maas, his narrative of his quest, transcripts of interviews and phone conversations, e-mails and more. All of this has been brought together into manuscript form by an anonymous editor whose presence is indicated through coy but increasingly tiresome long footnotes. In April 1953, Daniel Brodin translates an obscure Italian poem in his head to recite at a poetry reading but, improbably, someone recognizes it. Soon afterwards, he’s also caught stealing a book from a shop. Just a little plagiarism and shoplifting? It might have stayed that way until he met Gilles and Linda, fellow thieves, and their bodyguard, Jean-Michel, a big blond goon with Gérard Dépardieu’s nose and haircut. Now he’s known as “Klepto” and is part of a circle that drinks at the Café Sully and mixes with avant-garde and Existentialist figures. He’s content with being a nobody and writing his memoirs (the book within the book) – until Jean-Michel makes him a proposition.

In April 1953, Daniel Brodin translates an obscure Italian poem in his head to recite at a poetry reading but, improbably, someone recognizes it. Soon afterwards, he’s also caught stealing a book from a shop. Just a little plagiarism and shoplifting? It might have stayed that way until he met Gilles and Linda, fellow thieves, and their bodyguard, Jean-Michel, a big blond goon with Gérard Dépardieu’s nose and haircut. Now he’s known as “Klepto” and is part of a circle that drinks at the Café Sully and mixes with avant-garde and Existentialist figures. He’s content with being a nobody and writing his memoirs (the book within the book) – until Jean-Michel makes him a proposition.

Ken Kesey, who led a collaborative novel-writing workshop in which she participated in the late 1980s, once asked her what the best thing was that ever happened to her. Swimming, she answered, because it felt like the only thing she was good at. In the water she was at home and empowered. Kesey reassured her that swimming wasn’t her only talent: there is some truly dazzling writing here, veering between lyrical stream-of-consciousness and in-your-face informality.

Ken Kesey, who led a collaborative novel-writing workshop in which she participated in the late 1980s, once asked her what the best thing was that ever happened to her. Swimming, she answered, because it felt like the only thing she was good at. In the water she was at home and empowered. Kesey reassured her that swimming wasn’t her only talent: there is some truly dazzling writing here, veering between lyrical stream-of-consciousness and in-your-face informality. In January I had the tremendous opportunity to have a free personalized bibliotherapy appointment with Ella Berthoud at the School of Life in London. I’ve since read three of her prescriptions plus parts of a few others, but I still have several more awaiting me in the early days of 2019, and will plan to report back at some point on what I got out of all of them.

In January I had the tremendous opportunity to have a free personalized bibliotherapy appointment with Ella Berthoud at the School of Life in London. I’ve since read three of her prescriptions plus parts of a few others, but I still have several more awaiting me in the early days of 2019, and will plan to report back at some point on what I got out of all of them. Early April saw us visiting Wigtown, Scotland’s book town, for the first time. It was a terrific trip, but thus far I have not been all that successful at reading the 13 books that I bought! (Just two and a quarter so far.)

Early April saw us visiting Wigtown, Scotland’s book town, for the first time. It was a terrific trip, but thus far I have not been all that successful at reading the 13 books that I bought! (Just two and a quarter so far.) I did some “buddy reads” for the first time: Andrea Levy’s Small Island with Canadian blogger friends, including Marcie and Naomi; and West With the Night with Laila of

I did some “buddy reads” for the first time: Andrea Levy’s Small Island with Canadian blogger friends, including Marcie and Naomi; and West With the Night with Laila of

In October I won tickets to see a production of Angela Carter’s Wise Children at the Old Vic in London. Just a few weeks later I won tickets to see Barbara Kingsolver in conversation about Unsheltered at the Southbank Centre. I don’t often make it into London, so it was a treat to have bookish reasons to go and blogging friends to meet up with (Clare of

In October I won tickets to see a production of Angela Carter’s Wise Children at the Old Vic in London. Just a few weeks later I won tickets to see Barbara Kingsolver in conversation about Unsheltered at the Southbank Centre. I don’t often make it into London, so it was a treat to have bookish reasons to go and blogging friends to meet up with (Clare of

Two posts I planned but never got around to putting together would have commemorated the 50th anniversary of Thomas Merton’s death (I own several of his books but am most interested in reading The Seven-Storey Mountain, which celebrated its 70th birthday in October) and the 40th anniversary of the publication of The Snow Leopard by the late Peter Matthiessen. Perhaps I’ll try these authors for the first time next year instead.

Two posts I planned but never got around to putting together would have commemorated the 50th anniversary of Thomas Merton’s death (I own several of his books but am most interested in reading The Seven-Storey Mountain, which celebrated its 70th birthday in October) and the 40th anniversary of the publication of The Snow Leopard by the late Peter Matthiessen. Perhaps I’ll try these authors for the first time next year instead. Fathers (absent/difficult) + fatherhood in general: Educated by Tara Westover, And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison, The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman, In the Days of Rain by Rebecca Stott, Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott & March by Geraldine Brooks, The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan, Never Mind and Bad News by Edward St. Aubyn, The Reading Promise by Alice Ozma, How to Build a Boat by Jonathan Gornall, Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart, Normal People by Sally Rooney, Rosie by Rose Tremain, My Father and Myself by J.R. Ackerley, Everything Under by Daisy Johnson, Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss, Surfacing by Margaret Atwood, Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot, Blood Ties by Ben Crane, To Throw Away Unopened by Viv Albertine, Small Fry by Lisa Brennan-Jobs

Fathers (absent/difficult) + fatherhood in general: Educated by Tara Westover, And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison, The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman, In the Days of Rain by Rebecca Stott, Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott & March by Geraldine Brooks, The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan, Never Mind and Bad News by Edward St. Aubyn, The Reading Promise by Alice Ozma, How to Build a Boat by Jonathan Gornall, Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart, Normal People by Sally Rooney, Rosie by Rose Tremain, My Father and Myself by J.R. Ackerley, Everything Under by Daisy Johnson, Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss, Surfacing by Margaret Atwood, Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot, Blood Ties by Ben Crane, To Throw Away Unopened by Viv Albertine, Small Fry by Lisa Brennan-Jobs Greenland: A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley, This Cold Heaven by Gretel Ehrlich, Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg, On Balance by Sinéad Morrissey (the poem “Whitelessness”), Cold Earth by Sarah Moss, Crimson by Niviaq Korneliussen, The Library of Ice by Nancy Campbell

Greenland: A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley, This Cold Heaven by Gretel Ehrlich, Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg, On Balance by Sinéad Morrissey (the poem “Whitelessness”), Cold Earth by Sarah Moss, Crimson by Niviaq Korneliussen, The Library of Ice by Nancy Campbell Flying: Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine, West With the Night by Beryl Markham, Going Solo by Roald Dahl, Skyfaring by Mark Vanhoenacker

Flying: Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine, West With the Night by Beryl Markham, Going Solo by Roald Dahl, Skyfaring by Mark Vanhoenacker New Zealand: The Garden Party and Other Stories by Katherine Mansfield, To the Is-Land by Janet Frame, Dunedin by Shena Mackay

New Zealand: The Garden Party and Other Stories by Katherine Mansfield, To the Is-Land by Janet Frame, Dunedin by Shena Mackay

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them.

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them. Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:  A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her.

A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her.

Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Dear Fahrenheit 451

Dear Fahrenheit 451