Nine Days in Germany and What I Read, Part I: Berlin

We’ve actually been back for more than a week, but soon after our return I was felled by a nasty cold (not Covid, surprisingly), which has left me with a lingering cough and ongoing fatigue. Finally, I’m recovered just about enough to report back.

This Interrail adventure was more low-key than the one we took in 2016. The first day saw us traveling as far as Aachen, just over the border from France. It’s a nice small city with Christian and culinary history: Charlemagne is buried in the cathedral; and it’s famous for a chewy, spicy gingerbread called printen. Before our night in a chain hotel, we stumbled upon the mayor’s Green Party rally in the square – there was to be an election the following day – and drank and dined well. The Gin Library, spotted at random on the map, is an excellent and affordable Asian-fusion cocktail bar. My “Big Ben,” for instance, featured Tanqueray gin, lemon juice, honey, fresh coriander, and cinnamon syrup. Then at Hanswurst – Das Wurstrestaurant (cue jokes about finding the “worst” restaurant in Aachen!), a superior fast-food joint, I had the vegetarian “Hans Berlin,” a scrumptious currywurst with potato wedges.

The next day it was off to Berlin with a big bag of bakery provisions. For the first time, we experienced the rail cancellations and delays that would plague us for much of the next week. We then had to brave the only supermarket open in Berlin on a Sunday – the Rewe in the Hauptbahnhof – before taking the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz, the nearest station to our Airbnb flat.

It was all worth it to befriend Lemmy (the ginger one) and Roxanne. It’s a sweet deal the host has here: whenever she goes away, people pay her to look after her cats. At the same time as we were paying for a cat-sitter back home. We must be chumps!

I’ll narrate the rest of the trip through the books I read. I relished choosing relevant reads from my shelves and the library’s holdings – I was truly spoiled for choice for Berlin settings! – and I appreciated encountering them all on location.

As soon as we walked into the large airy living room of the fifth-floor Airbnb flat, I nearly laughed out loud, for there in the corner was a monstera plant. The trendy, minimalist décor, too, was just like that of the main characters’ place in…

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes]

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss)

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

- Reichstag (Photos 1, 2 and 4 by Chris Foster)

- Reichstag tower designed by Norman Foster

- The Philharmonic

- Brandenburg Gate (Photos 1-3 by Chris Foster)

- Postdam’s Park Sanssouci

- Wen Cheng noodles

- Brammibal’s vegan doughnuts

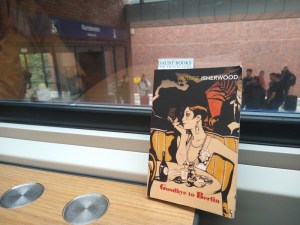

I brought along another novella that proved an apt companion for our explorations of the city. Even just spotting familiar street and stop names in it felt like reassurance.

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri (2022)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library) ![]()

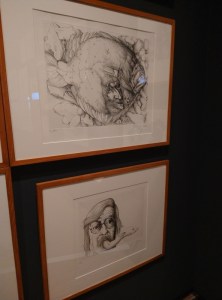

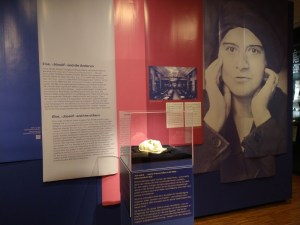

We spent a drizzly and slightly melancholy first day and final morning making pilgrimages to Jewish graveyards and monuments to atrocities, some of them nearly forgotten. I got the sense of a city that has been forced into a painful reckoning with its past – not once but multiple times, perhaps after decades of repression. One morning we visited the claustrophobic monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and, in the Tiergarten, the small memorials to the Roma and homosexual victims of the Holocaust. The Nazis came for political dissidents and the disabled, too, as I was reminded at the Topography of Terrors, a free museum where brutal facts are laid bare. We didn’t find the courage to go in as the timeline outside was confronting enough. I spotted links to the two historical works I was reading during my stay (Stella the red-haired Jew-catcher in the former and Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute in the latter). As I read both, I couldn’t help but think about the current return of fascism worldwide and the gradual erosion of rights that should concern us all.

Aimée and Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fischer (1994; 1995)

[Translated from German by Edna McCown]

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Milena and Margarete: A Love Story in Ravensbrück by Gwen Strauss]

The Lilac People by Milo Todd (2025)

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss)

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Under the Pink Triangle by Katie Moore (set in Dachau)]

We might have been at the Eldorado in the early 1930s on the evening when we ventured out to the bar Zosch for a “New Orleans jazz” evening. The music was superb, the German wine tasty, the whole experience unforgettable … but it sure did feel like being in a bygone era. We’re so used to the indoor smoking ban (in force in the UK since 2007) that we didn’t expect to find young people chain-smoking rollies in an enclosed brick basement, and got back to the flat with our clothes reeking and our lungs burning.

It was good to see visible signs of LGTBQ support in Berlin, though they weren’t as prevalent as I perhaps expected.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

Other Berlin highlights: a delicious vegetarian lunch at the canteen of an architecture firm, the Ritter chocolate shop, and the pigeons nesting on the flat balcony – the chicks hatched on our final morning!

And a belated contribution to Short Story September:

Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue (2006)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Trip write-up to be continued (tomorrow, with any luck)…

Scottish Travels & Book Haul: Wigtown, Arran, Islay and Glasgow

When I was a kid, one-week vacations were rare and precious – Orlando or Raleigh for my dad’s church conferences, summer camp in Amish-country Pennsylvania, spring break with my sister in California – and I mourned them when they were over. As an adult, I find that after a week I’m ready to be home … and yet just days after we got back from Scotland, I’m already wondering why I thought everyday life was so great. Oh well. I like to write up my holidays because otherwise it’s all too easy to forget them. This one had fixed start and end points – several days of beetle recording in Galloway for my husband; meeting up with my sister and nephew in Glasgow one evening the next week – and we filled in the intervening time with excursions to two new-to-us Scottish islands; we’re slowly collecting them all.

First Stop, Wigtown

Hard to believe it had been over five years since our first trip to Wigtown. The sleepy little town had barely changed; a couple of bookshops had closed, but there were a few new ones I didn’t remember from last time. The weather was improbably good, sunny and warm enough that I bought a pair of cutoffs at the Community Shop. Each morning my husband set off for bog or beach or wood for his fieldwork and I divided the time until he got back between bits of paid reviewing, reading and book shopping. Our (rather spartan) Airbnb apartment was literally a minute’s walk into town and so was a perfect base.

I paced myself and parcelled out the eight bookshops and several other stores that happen to sell books across the three and a bit days that I had. It felt almost like living there – except I would have to ration my Reading Lasses visits, as a thrice-weekly coffee-and-cake habit would soon get expensive as well as unhealthy. (I spent more on books than on drinks and cakes over the week, though only ~25% more: £44 vs. £32.)

I also had the novelty of seeing my husband interact with his students when we were invited to a barbecue at one’s family home on the Mull of Galloway – and realizing that we’re almost certainly closer in age to the mum than to the student. Getting there required two rural bus journeys to the middle of nowhere, an experience all in itself.

‘Pro’ tips: New Chapter Books was best for bargains, with sections for 50p and £1 paperbacks and free National Geographics. Well-Read Books was good for harder-to-find fiction: among my haul were two Jane Urquhart novels, and the owner was knowledgeable and pleasant. Byre Books carries niche subjects and has scant opening hours, but I procured two poetry collections and a volume of Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals. The Old Bank Bookshop and The Bookshop are the two biggest shops; wander for an hour or more if you can. The Open Book tends to get castoffs from other shops and withdrawn library stock, but I still made two purchases and ended up being the first customer for the week’s hosts: Debbie and Jenny, children’s book authors and long-distance friends from opposite coasts of the USA. Overall, I was pleased with my novella, short story and childhood memoir acquisitions. A better haul than last time.

‘Celebrity’ sightings: On our walk down to the bird hide on the first evening, we passed Jessica Fox, an American expat who’s been influential in setting up the literary festival and The Open Book. She gave us a cheery “hello.” I also spotted Ben of The Bookshop Band twice, once in Reading Lasses and another time on his way to the afternoon school run. Both times he had the baby in tow and I decided not to bother him, not even to introduce myself as one of their Patreon supporters.

On our last morning in town, we lucked out and found Shaun Bythell behind the counter at The Bookshop. He’d just taken delivery of a book-print kilt his staff surprised him by ordering with his credit card, and Nicky (not as eccentric as she’s portrayed in Diary of a Bookseller; she’s downright genteel, in fact) had him model it. He posted a video to Facebook that includes The Open Book hosts on the 23rd, if you wish to see it, and his new cover photo shows him and his staff members wearing the jackets that match the kilt. I bought a few works of paperback fiction and then got him to sign my own copies of two of his books.

As last time, he was chatty and polite, taking an interest in our travels and exhorting us to come back sooner than five years next time. I congratulated him on his success and asked if we could expect more books. He said that depends on his publisher, who worry the market is saturated at the moment, though he has another SIX YEARS of diaries in draft form and the Remainders of the Day epilogue would be quite different if he wrote it now. Tantalizing!

Note to self: Next time, plan to be in town through a Friday evening – we left at noon, so I was sad to miss out on a Beth Porter (the other half of The Bookshop Band) children’s songs concert at Foggie Toddle Books at 3:00, followed by a low-key cocktail party at The Open Book at 5:30 – but not until a Monday, as pretty much everything shuts that day. How I hope someone buys Reading Lasses (the owner is retiring) and maintains the café’s high standard!

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Arran

Our short jaunt to Arran started off poorly with a cancelled ferry sailing, leaving us stranded in Ardrossan (which Bythell had almost prophetically dubbed a “sh*thole” that morning!) for several hours until the next one, and we struggled with a leaky rear tyre and showery weather for much of the time, but we were still enamoured with this island that calls itself “Scotland in miniature.” That was particularly delightful for me because I come from the state nicknamed “America in miniature,” Maryland. This Airbnb was plush by comparison, we obtained excellent food from the Blackwater Bakehouse and a posh French takeaway, and we enjoyed walks at the Machrie stone circles and Brodick Castle as well as at the various bays (one with a fossilized dinosaur footprint) that we stopped off at on our driving tour.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Islay

Islay is a tourist mecca largely because of its nine distilleries – what a pity we don’t care for whiskey! – but we sought it out for its wildlife and scenery, which were reminiscent of what we saw in the Outer Hebrides last year. Our B&B was a bit fusty (there was a rotary phone in the hall!), but we had an unbeatable view from our window and enjoyed visiting two RSPB reserves. The highlight for me was the walk to the Mull of Oa peninsula and the cow-guarded American Monument, which pays tribute to the troops who died in two 1918 naval disasters – a torpedoed boat and a shipwreck – and the heroism of locals who rescued survivors.

We spent a very rainy Tuesday mooching from one distillery shop to another. There are two gin-makers whose products we were eager to taste, but we also relished our mission to buy presents for two landmark birthdays, one of an American friend who’s a whiskey aficionado. Even having to get the tyre replaced didn’t ruin the day. There’s drink aplenty on Islay, but quality food was harder to acquire, so if we went back we’d plump for self-catering.

Incidental additional hauls: I found this 50th anniversary Virago tote bag under a bench at Bowmore harbour after our meal at Peatzeria. I waited a while to see if anyone would come back for it, but it was so sodden and sandy that it must have been there overnight. I cleaned it up and brought home additional purchases in it: two secondhand finds at a thrift store in Tarbert, the first town back on the mainland, and a Knausgaard book I got free with my card points from a Waterstones in Glasgow.

Glasgow

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

With our one day in Glasgow, we decided to prioritize the Burrell Collection, due to the enthusiastic recommendations from Susan, our Arran hosts, and Bill Bryson in Notes on a Small Island (“Among the city’s many treasures, none shines brighter, in my view”). It’s a museum with a difference, housed in a custom-built edifice that showcases the wooded surroundings as much as the stunning objects. We were especially partial to the stained glass.

Our whistle-stop city tour also included a walk past the cathedral, a ramble through the Necropolis (where, pleasingly, I saw a grave for one Elizabeth Pringle), and the Tenement Museum, a very different sort of National Trust house that showed how one woman, a spinster and hoarder, lived in the first half of the 20th century. Then on to an exceptional seafood-heavy meal at Kelp, also recommended by Susan, and an all-too-brief couple of hours with my family at their hotel and a lively pub.

We keep returning to Scotland. Where next in a few years? Possibly the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides, which we didn’t have time for last year, or the more obscure of the Inner Hebrides, before planning return visits to some favourites. All the short ferry rides were smooth this time around, so I can cope with the thought of more.

We got home to find our mullein plants attempting to take over the world.

Adventuring (and Reading) in the Outer Hebrides

Islands are irresistible for the unique identities they develop through isolation, and the extra effort that it often takes to reach them. Over the years, my husband and I have developed a special fondness for Britain’s islands – the smaller and more remote the better. After exploring the Inner Hebrides in 2005 and Orkney and Shetland in 2006, we always intended to see more of Scotland’s islands; why ever did we leave it this long?

Rail strikes and cancelled trains threatened our itinerary more than once, so it was a relief that we were able to go, even at extra cost. Our back-up plan left us with a spare day in Inverness, which we filled with coffee and pastries outside the cathedral, browsing at Leakey’s bookshop, walking along the River Ness and in the botanical gardens, and a meal overlooking the 19th-century castle.

Then it was on to the Outer Hebrides at last, via a bus ride and then a ferry to Stornoway in Lewis, the largest settlement in the Western Isles. Here we rented a car for a week to allow us to explore the islands at will. We were surprised at how major a town Stornoway is, with a big supermarket and slight suburban sprawl – yet it was dead on the Saturday morning we went in to walk around; not until 11:30 was there anything like the bustle we expected.

We’d booked three nights in a tiny Airbnb house 15 minutes from the capital. First up on our tourist agenda was Callanish stone circle, which we had to ourselves (once the German coach party left). Unlike at Stonehenge, you can walk in among the standing stones. The rest of our time on Lewis went to futile whale watching, the castle grounds, and beach walks.

This post threatens to become a boring rundown, so I’ll organize the rest thematically, introduced by songs by Scottish artists.

“I’ll Always Leave the Light On” by Kris Drever

Long days: The daylight lasts longer so far north, so each day we could plan activities not just for the morning and afternoon but late into the evening. At our second stop – three nights in another Airbnb on North Uist – we took walks after dinner, often not coming back until 10 p.m., at which point there was still another half-hour until sunset.

“Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” by Travis

Weather: We got a mixture of sun and clouds. It rained at least a bit on most days, and we got drenched twice, walking out to an eagle observatory on Harris (where we saw no eagles, as they are too sensible to fly in the rain) and dashing back to the car from a coastal excursion. I was doomed to wearing plastic bags around my feet inside my disintegrating hiking boots for the rest of the trip. There was also a strong wind much of the time, which made it feel colder than the temperature suggested – I often wore my fleece and winter hat.

A witty approach to weather forecasting. (Outside the shop/bistro on Berneray.)

“St Kilda Wren” by Julie Fowlis

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Wildlife: The Outer Hebrides is a bastion for some rare birds: the corncrake, the red-necked phalarope, and both golden and white-tailed eagles. Thanks to intel gleaned from Twitter, my husband easily found a phalarope swimming in a small roadside loch. Corncrakes hide so well they are virtually impossible to see, but you will surely hear their rasping calls from the long grass. Balranald is the westernmost RSPB reserve and a wonderful place to hear corncrakes and see seabirds flying above the machair (wildflower-rich coastal grassland). No golden eagles, but we did see a white-tailed eagle flying over our accommodation on our last day, and short-eared owls were seemingly a dime a dozen. We were worried we might see lots of dead birds on our trip due to the avian flu raging, but there were only five – four gannets and an eider – and a couple looked long dead. Still, it’s a distressing situation.

We also attended an RSPB guided walk to look for otters and did indeed spot one on a sea loch. It happened to be the Outer Hebrides Wildlife Festival week. Our guide was knowledgeable about the geography and history of the islands as well.

Badges make great, cheap souvenirs!

St. Kilda: This uninhabited island really takes hold of the imagination. It can still be visited, but only via a small boat through famously rough seas. We didn’t chance it this time. I might never get there, but I enjoy reading about it. There’s a viewing point on North Uist where one can see out to St. Kilda, but it was only the vaguest of outlines on the hazy day we stopped.

“Traiveller’s Joy” by Emily Smith

Additional highlights:

- An extended late afternoon tea at Mollans rainbow takeaway shed on Lewis. Many of the other eateries we’d eyed up in the guidebook were closed, either temporarily or for good – perhaps an effect of Covid, which hit just after the latest edition was published.

- A long reading session with a view by the Butt of Lewis, which has a Stevenson lighthouse.

- Watching mum and baby seals playing by the spit outside our B&B window on Berneray.

- Peat smoked salmon. As much of it as I could get.

- A G&T with Harris gin (made with kelp).

“Dear Prudence” (Beatles cover) by Lau

Surprises:

- Gorgeous, deserted beaches. This is Luskentyre on Harris.

- No midges to speak of. The Highlands are notorious for these biting insects, but the wind kept them away most of the time we were on the islands. We only noticed them in the air on one still evening, but they weren’t even bad enough to deploy the Avon Skin So Soft we borrowed from a neighbour.

- People still cut and burn peats for fuel. Indeed, when we stepped into the Harris gin distillery for a look around, I was so cold and wet that I warmed my hands by a peat fire! Even into the 1960s, people lived in primitive blackhouses, some of which have now been restored as holiday rentals. The one below is run as a museum.

- Not far outside Stornoway is the tiny town of Tong. We passed through it each day. Here Mary Anne MacLeod was born in 1912. If only she’d stayed on Lewis instead of emigrating to New York City, where she met Fred Trump and had, among other children, a son named Donald…

- Lord Leverhulme, founder of Unilever, bought Lewis in 1918 and part of Harris the next year. He tried to get crofters to work in his businesses, but all his plans met with resistance and his time there was a failure, as symbolized by this “bridge to nowhere” (Garry Bridge). His legacy is portrayed very differently here compared to in Port Sunlight, the factory workers’ town he set up in Merseyside.

- The most far-flung Little Free Library I’ve ever visited (on Lewis).

- Visits from Lulu the cat at our North Uist Airbnb.

“Wrapped Up in Books” by Belle and Sebastian

What I read: I aimed for lots of relevant on-location reads. I can’t claim Book Serendipity: reading multiple novels set on Scottish islands, it’s no surprise if isolation, the history of the Clearances, boat rides, selkies and seabirds recur. However, the coincidences were notable for one pair, Secrets of the Sea House by Elisabeth Gifford and Night Waking by Sarah Moss, a reread for me. I’ll review these two together, as well as The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen (inspired by a real incident that occurred on North Uist in 1980), in full later this week.

I also read about half of Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie, a reread for me; its essays on gannets and St. Kilda chimed with the rest of my reading. Marram, Leonie Charlton’s memoir of pony trekking through the Outer Hebrides, will form part of a later 20 Books of Summer post thanks to the flora connection, as will Jon Dunn’s Orchid Summer, one chapter of which involves a jaunt to North Uist to find a rare species.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

I also acquired four books on the trip: one from the Little Free Library and three from Inverness charity shops.

I started reading all three in the bottom pile, and read a few more books on my Kindle, two of them for upcoming paid reviews. The third was:

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

On my recommendation, my husband read Love of Country by Madeleine Bunting and The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, two excellent nonfiction books about Britain’s islands and coastline.

“Other Side of the World” by KT Tunstall

General impressions: We weren’t so taken with Lewis on the whole, but absolutely loved what we saw of Harris on our drive to the ferry to Berneray and wished we’d allotted it more time. While we only had one night on Berneray and mostly saw it in the rain, we thought it a lovely little place. It only has the one shop, which doubles as the bistro in the evenings – warned by the guidebook that this is the only place to eat on the island, we made our dinner reservation many weeks in advance. The following morning, as we ate our full Scottish cooked breakfast, I asked the B&B owner what led him to move from England to “the ends of the earth.” He took mild objection to my tossed-off remark and replied that the islands are more like “the heart of it all.” Thanks to fast Internet service, remote working is no issue.

We are more than half serious when we talk about moving to Scotland one day. We love Edinburgh, though the tourists might drive us mad, and enjoyed our time in Wigtown four years ago. I’d like to think we could even cope with island life in Orkney or the Hebrides. We imagine them having warm, tight-knit communities, but would newcomers feel welcome? With only one major supermarket in the whole Western Isles, would we find enough fresh fruit and veg? And however would one survive the bleakness of the winters?

North Uist captivated us right away, though. Within 15 minutes of driving onto the island via a causeway, we’d seen three short-eared owls and three red deer stags, and we got great views of hen harriers and other raptors. One evening we found ourselves under what seemed to be a raven highway. It felt unlike anywhere else we’d been: pleasingly empty of humans, and thus a wildlife haven.

The long journey home: The public transport nightmares of our return trip put something of a damper on the end of the holiday. We left the islands via a ferry to Skye, where we caught a bus. So far, so good. Our second bus, however, broke down in the middle of nowhere in the Highlands and the driver plus we five passengers were stuck for 3.5 hours awaiting a taxi we thought would never come. When it did, it drove the winding road at terrifying speed through the pitch black.

Grateful to be alive, we spent the following half-day in Edinburgh, bravely finding brunch, the botanic gardens and ice cream with our heavy luggage in tow. The final leg home, alas, was also disrupted when our overcrowded train to Reading was delayed and we missed the final connection to Newbury, necessitating another taxi – luckily, both were covered by the transport operators, and we’ll also reclaim for our tickets. Much as we believe in public transport and want to support it, this experience gave us pause. Getting to and around Spain by car was so much easier, and that trip ended up a lot cheaper, too. Ironic!

Guarding the bags in Edinburgh

“Take Me Back to the Islands” by Idlewild

Next time: On this occasion we only got as far south as Benbecula (which, pleasingly, is pronounced Ben-BECK-you-luh). In the future we’d think about starting at the southern tip and seeing Barra, Eriskay and South Uist before travelling up to Harris. We’ve heard that these all have their own personalities. Now, will we get back before many more years pass?

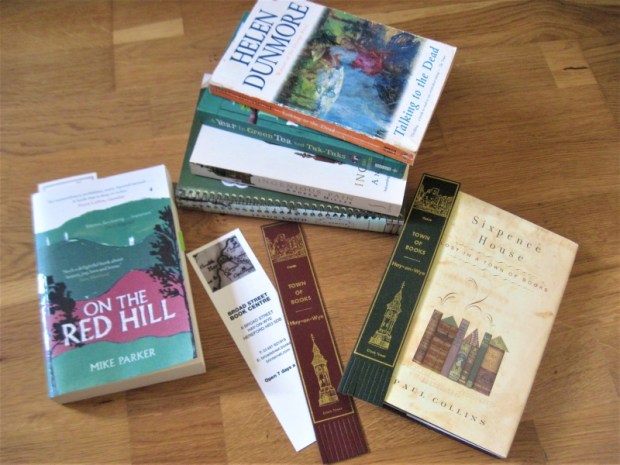

Making Plans for a Return to Hay-on-Wye & A Book “Overhaul”

Somehow it’s been nearly 3.5 years since our last trip to Hay-on-Wye, the Book Town of Wales (I wrote about that April 2017 visit here). This coming weekend will be our seventh trip to Hay, one of our favorite places. We’ve booked an Airbnb in nearby English hamlet Cusop Dingle for two nights, so it’s a pretty short break, but longer than the weekend away we managed last month – reduced to only 36 hours by the cat’s poorly timed but ultimately minor one-day illness.

I’ve acquired many, many books from the free mall bookshop over the past year. (It’s now closed permanently, alas.) And I had no shortage of additional incomers during lockdown, via the unofficial Little Free Library I started and orders I placed with independent bookstores and publishers. So you could say I don’t need a book-buying trip to Hay. But 1) it’s never a question of need, is it? and 2) We want to continue to support the town, which will have been hit hard by temporary closures and by its annual literary festival being purely online this year.

I have no particular plans for what to buy this time, so will just see what takes my fancy. There are noticeably fewer bookshops than when we first started visiting Hay in 2004, but among the dozen or so remaining are some truly excellent shops like Addyman Books, the Hay Cinema Bookshop, and Booth’s Bookshop. Our best bargains last time were from the Oxfam charity shop and the honesty shelves around the castle, so those will likely be our first ports of call, and from there we’ll let whimsy be our guide. Saturday and Monday will be for wandering the town and book shopping, while Sunday will include countryside walks around Hay Bluff. We also hope to explore some eatery options we’ve not tried before.

An Overhaul of Last Trip’s Book Purchases

Simon of Stuck in a Book runs a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With his permission, I’m borrowing the title and format to look back at what I bought in Hay last time.

Date of haul: April 2017

Location: Hay-on-Wye

Number of books bought: 18

Had already read: (3/18)

- How to Age by Anne Karpf

- From Heaven Lake by Vikram Seth

- Tamara Drewe by Posy Simmonds – It’s on my shelf for rereading.

Have read since then: (5/18)

- Every Man for Himself by Beryl Bainbridge [resold]

- Fillets of Plaice by Gerald Durrell

- A Student of Weather by Elizabeth Hay (!)

- The Dead Beat by Marilyn Johnson

- Cats in May by Doreen Tovey

BUT also read from my hubby’s pile (not pictured):

- Sold for a Farthing by Clare Kipps

- All the Presidents’ Pastries by Roland Mesnier

- Second Nature by Michael Pollan

- A Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

DNFed: (3/18)

- Life & Times of Michael K by J.M. Coetzee [resold]

- We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates – Might try this one again another time.

- Ghostwalk by Rebecca Stott [given away]

Resold unread: (1/18)

- Family and Friends by Anita Brookner – I’d added it to the Oxfam pile to make up a 5 for £1 stack, but then didn’t enjoy Booker winner Hotel du Lac enough to try another by Brookner.

Total still unread: 6

Total no longer owned: 4

This is not too bad a showing overall, though it does reveal my habit of buying books and letting them sit around for years unread. (Surely I’m not alone in this?!)

The six purchases still to read are two cat-themed anthologies for reading piecemeal, plus these four – two fiction and two non-:

- Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore

- Ingenious Pain by Andrew Miller

- Jesus Land by Julia Scheeres

- A Year in Green Tea and Tuk-Tuks by Rory Spowers

To force myself to get to them, these are the four I’ve packed for reading in the car and while in Hay. I’m also bringing, to read on location: 1) On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, a Wainwright Prize-shortlisted memoir about life in the Welsh countryside (I’m about 40 pages into it already); and 2) Sixpence House, which I’ve read several times before and consider among my absolute favorite books; it’s Paul Collins’s memoir about finding a temporary home and work among the bookshops of Hay.

I’ll be back on Tuesday with this year’s book haul plus photos and notes on how we found the town this time around. (But first, Six Degrees of Separation will post on Saturday while I’m away.)

“Being the Expert” on Women’s Religious Memoirs Again: Unfollow & Leaving the Witness

I’ve fallen behind on the weekly prompts for Nonfiction November, but wanted to post a follow-up to my 2018 list of a baker’s dozen of memoirs I’ve read that explore women’s religious experiences. I’ve read a couple more this year that are worth adding to the list; in addition to their themes of doubt and making a new life outside the church, they also share an interesting detail: it’s an online friend that goads each author into questioning her beliefs. Even if you aren’t typically interested in this subgenre, you’ve likely heard of Unfollow because of the high-profile story behind it. (This week is hosted by Katie of Doing Dewey.)

I’ve fallen behind on the weekly prompts for Nonfiction November, but wanted to post a follow-up to my 2018 list of a baker’s dozen of memoirs I’ve read that explore women’s religious experiences. I’ve read a couple more this year that are worth adding to the list; in addition to their themes of doubt and making a new life outside the church, they also share an interesting detail: it’s an online friend that goads each author into questioning her beliefs. Even if you aren’t typically interested in this subgenre, you’ve likely heard of Unfollow because of the high-profile story behind it. (This week is hosted by Katie of Doing Dewey.)

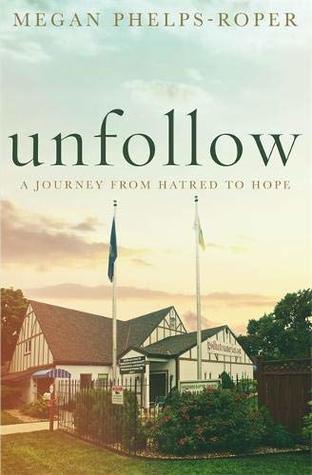

Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope, Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church by Megan Phelps-Roper

“God hates f*gs.” If you know one thing about Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas, it’s that this slogan plastered their signs and was part of their armory of in-your-face chants at nationwide protests.

Fred Phelps in 2002. (User Rudolf 1922 on sv.wikipedia.)

Megan Phelps-Roper grew up in the Church, which was founded by her grandfather, Fred Phelps, and made up mostly of her extended family: Phelps had 13 children, and Phelps-Roper is one of 11. In 1989 Phelps learned that nearby Gage Park was a gay cruising spot and wrote in disgust to the mayor and other city officials. In a sense, he never got over it. The anti-homosexuality message would become Westboro’s trademark, at least until the church started its picketing of military funerals after the Iraq War – which, like 9/11, was interpreted as being God’s just punishment of American immorality.

By portraying it from the inside and recreating her shifting perspective from early childhood onwards, Phelps-Roper initially makes her extreme upbringing seem normal. After all, it’s the only thing she knew, and it never would have occurred to her that her family could be wrong. The Phelpses were fiercely intelligent and also ran a law firm, so it’s impossible to just dismiss them as redneck idiots. Frequent passages from the King James Bible appear in italics to echo the justifications the Church cited for its beliefs and actions.

Only gradually did doubts start to creep in for the author as various uncles and brothers left the church. Phelps-Roper was even the voice of Westboro on Twitter, but defending funeral protests became increasingly difficult for her. Two things brought her to a breaking point. First, in something of a coup, the Church appointed a new body of elders – all male, of course – who instituted ever more draconian rules, such as a dress code for women, and effectively removed her mother from leadership. (Ultimately, they would kick the dying Fred Phelps himself out of the church.) Secondly, the Church started to spread fake news via doctored photos. For example, they claimed to be protesting a royal wedding in London, when in fact Westboro members never go anywhere the First Amendment can’t protect them.

Only gradually did doubts start to creep in for the author as various uncles and brothers left the church. Phelps-Roper was even the voice of Westboro on Twitter, but defending funeral protests became increasingly difficult for her. Two things brought her to a breaking point. First, in something of a coup, the Church appointed a new body of elders – all male, of course – who instituted ever more draconian rules, such as a dress code for women, and effectively removed her mother from leadership. (Ultimately, they would kick the dying Fred Phelps himself out of the church.) Secondly, the Church started to spread fake news via doctored photos. For example, they claimed to be protesting a royal wedding in London, when in fact Westboro members never go anywhere the First Amendment can’t protect them.

All along, Phelps-Roper had been corresponding with “C.G.,” an online acquaintance with whom she played Words with Friends. Chad gently encouraged her to ask why Westboro believed as it did, and to unpick rather than ignore any doctrines that didn’t make sense. “What if we’re wrong? What if this isn’t The Place led by God Himself? What if we’re just people?” she wondered. In November 2012, she and her sister Grace left the Church and the family home, where she’d lived until age 26, and retreated to a Deadwood, South Dakota Airbnb to hike, read and think about what they’d left behind and what came next. I’d had just about enough of Westboro and its infighting by that point in the book – the chapter about her leaving gets a little melodramatic – so, like the author, I was glad to move on to another setting, and this interlude ended up being my favorite section.

Westboro Baptist Church demonstration outside the Virginia Holocaust Museum, March 2010. (JCWilmore [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)%5D.)

Note: Westboro was the subject of a Louis Theroux documentary in 2006, and in a nice full-circle moment, he’s now interviewing Phelps-Roper on some of her UK book tour spots. And, in another lovely aside, she married C.G.

My rating:

With thanks to riverrun for the free copy for review.

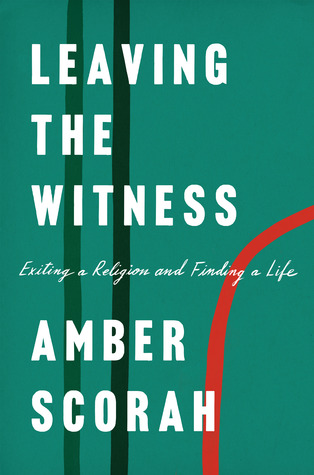

Leaving the Witness: Exiting a Religion and Finding a Life by Amber Scorah

Like In the Days of Rain by Rebecca Stott, this is the story of growing up in a cult and what happens when, as an adult, a woman has to build a new life free from the constraints – but also unmoored from the comforting framework – of a previously unquestioned belief system. Scorah grew up in Vancouver’s community of Jehovah’s Witnesses and, although she was temporarily disfellowshipped as a teenager for having premarital sex, the faith was her home and gave her a sense of purpose. Witnesses are discouraged from attending university or pursuing careers; without exception, they’re expected to preach and win converts – the only task worth engaging in given that the world is headed towards Armageddon.

Scorah and her husband went to China as clandestine JW missionaries. Her Mandarin skills were good enough that she could become friends with her English-language pupils and then start to talk to them about religion. In the meantime, she became an early podcast host with the program “Dear Amber,” which offered advice on the Chinese language and culture. She embarked on a flirtatious correspondence with one of her regular listeners, Jonathan from Los Angeles, who goaded her into rethinking everything she’d been taught to believe. “I was questioning with a mind that had been trained not to. It was highly uncomfortable.”

Scorah and her husband went to China as clandestine JW missionaries. Her Mandarin skills were good enough that she could become friends with her English-language pupils and then start to talk to them about religion. In the meantime, she became an early podcast host with the program “Dear Amber,” which offered advice on the Chinese language and culture. She embarked on a flirtatious correspondence with one of her regular listeners, Jonathan from Los Angeles, who goaded her into rethinking everything she’d been taught to believe. “I was questioning with a mind that had been trained not to. It was highly uncomfortable.”

As her marriage and faith simultaneously crumbled, Scorah had to decide what was left to form the foundation of a new life on her own in New York City. “My eye-glazing peace, unquestioning contentment, and eternal life were gone, and the time ahead of me was filled with people I didn’t yet know, uncertainty about the future, and, one day, death.” I was absorbed in the bittersweet outworkings of this before and after: a process of losing faith and deciding what’s next.

The final chapter is a whirlwind tour through her first years in NYC, including the tragic death of her infant son, Karl. This makes for something of an abrupt end to the book; I might have liked to get as much detail on all this as we got about the time in China. But it was clearly a deliberate decision to present such life and death matters from a hard-won secular perspective, without the false balm of a religion that promises she’ll see her son again. There’s a lot of secrecy about the Jehovah’s Witnesses, so this is a rare insider’s view as well as a wrenching account of loss and starting over.

My rating:

Full disclosure: Amber Scorah offered me a copy through a Facebook group we are both a part of.

Thanks to her and Viking for sending a free copy for review.

Can you see yourself reading either of these books?

Thomas Hardy Tourism in Dorset

We fancied a short break before term starts (my husband is a teaching associate in university-level biology), so booked a cheap Airbnb room in Bridport for a couple of nights and headed to Dorset on Wednesday, stopping at the Thomas Hardy birthplace cottage on the way down and returning on Friday via Max Gate, the home he designed on the outskirts of Dorchester.

I’d been to both before, but over 15 years ago. In the summer of 2004, at the end of my study abroad year, I used a travel grant from my college to spend a week in Dorset and Nottinghamshire, researching the sense of place in the works of Hardy and D.H. Lawrence. I marvel at my bravery now: barely out of my teens, there I was traveling alone by train and bus to places I’d never been before, finding my own B&B accommodation, and taking long countryside walks to arrive at many sites on foot.

Max Gate

I found that much had changed in 15 years. The main difference is that both properties have now been given the full National Trust treatment, with an offsite visitor centre and café down the lane from Hardy’s Cottage, and the upper floors of Max Gate now open to the public after the end of private tenancies in 2011.* This could be perceived as a good thing or a bad thing: Everything is more commercial and geared towards tourists, yes, but also better looked after and more inviting thanks to visitor income and knowledgeable volunteers. Fifteen years ago I remember the two sites being virtually deserted, with the cottage’s garden under black plastic and awaiting a complete replanting. Now it’s flourishing with flowers and vegetables.

*In 2004 only a few ground-floor rooms were open to the public. I happened to spot in the visitor’s book that novelist Vikram Seth had signed in just before me. When I made the caretakers aware of this, they expressed admiration for his work and offered him an exclusive look at the study where Hardy wrote Tess of the d’Urbervilles. I got to tag along! The story is less impressive since it’s been a standard part of the house tour for eight years now, but I still consider it a minor claim to fame.

The thatched cottage doesn’t possess anything that belonged to the Hardy family, but is decorated in a period style that’s true to its mid-1800s origin. Hardy was born here and remained until his early thirties, completing an architecture apprenticeship and writing his first few books, including Under the Greenwood Tree. Even if you’re not particularly familiar with or fond of Hardy’s work, I’d recommend an afternoon at the cottage for a glimpse of how simple folk lived in that time. With wood smoke spooling out of the chimney and live music emanating from the door – there are two old fiddles in the sitting room that guests are invited to play – it was a perfectly atmospheric visit.

Afterwards, we headed to Portland, an isthmus extending from the south coast near Weymouth and known for its stone. It’s the setting of The Well-Beloved, which Hardy issued in serial form in 1892 and revised in 1897 for its book publication. Jocelyn Pierston, a sculptor whose fame is growing in London, returns to “the Isle of Slingers” (Hardy gave all his English locales made-up names) for a visit and runs into Avice Caro, a childhood friend. On a whim, he asks her to marry him. Before long, though, following a steamy (for Victorian literature, anyway) scene under an upturned boat during a storm, he transfers his affections to Miss Bencomb, the daughter of his father’s rival stone merchant. The fickle young man soon issues a second marriage proposal. I read the first 30 pages, but that was enough for me.

Afterwards, we headed to Portland, an isthmus extending from the south coast near Weymouth and known for its stone. It’s the setting of The Well-Beloved, which Hardy issued in serial form in 1892 and revised in 1897 for its book publication. Jocelyn Pierston, a sculptor whose fame is growing in London, returns to “the Isle of Slingers” (Hardy gave all his English locales made-up names) for a visit and runs into Avice Caro, a childhood friend. On a whim, he asks her to marry him. Before long, though, following a steamy (for Victorian literature, anyway) scene under an upturned boat during a storm, he transfers his affections to Miss Bencomb, the daughter of his father’s rival stone merchant. The fickle young man soon issues a second marriage proposal. I read the first 30 pages, but that was enough for me.

St. George’s Church, Portland, in a Christopher Wren style.

[I failed on classics or doorstoppers this month, alas, so look out for these monthly features to return in October. I did start The Warden by Anthony Trollope, my first of his works since Phineas Finn in 2005, with the best of intentions, and initially enjoyed the style – partway between Dickens and Hardy, and much less verbose than Trollope usually is. However, I got bogged down in the financial details of Septimus Harding’s supposed ripping-off of the 12 old peasants who live in the local hospital (as in a rest center for the aged and infirm, like the Hospital of St Cross at Winchester). He never should have had his comfortable £800 a year, it seems. His son-in-law, the archdeacon Dr. Grantly, and his would-be son-in-law, gadfly John Bold, take opposing sides as Harding looks to the legal and religious authorities for advice. I read the first 125 pages but only briefly skimmed the rest. Given how much longer the other five volumes are, I doubt I’ll ever read the rest of the Barchester Chronicles.]

[I failed on classics or doorstoppers this month, alas, so look out for these monthly features to return in October. I did start The Warden by Anthony Trollope, my first of his works since Phineas Finn in 2005, with the best of intentions, and initially enjoyed the style – partway between Dickens and Hardy, and much less verbose than Trollope usually is. However, I got bogged down in the financial details of Septimus Harding’s supposed ripping-off of the 12 old peasants who live in the local hospital (as in a rest center for the aged and infirm, like the Hospital of St Cross at Winchester). He never should have had his comfortable £800 a year, it seems. His son-in-law, the archdeacon Dr. Grantly, and his would-be son-in-law, gadfly John Bold, take opposing sides as Harding looks to the legal and religious authorities for advice. I read the first 125 pages but only briefly skimmed the rest. Given how much longer the other five volumes are, I doubt I’ll ever read the rest of the Barchester Chronicles.]

My other appropriate reading of the trip was Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively, in which Claudia Hampton, a popular historian now on her deathbed, excavates the layers of her personal past and dwells on the subjectivity of history and memory. She grew up in Dorset and mentions ammonites and rock strata, which we encountered on our beach walks.

Bridport isn’t so well known, but we thought it a lovely place, full of pleasant cafés, pubs and charity shops. It also has an independent bookshop and two secondhand ones, and we had an excellent meal of dumplings and noodle bowls at the English/Asian fusion restaurant Dorshi. It’s tucked away down an alley, but well worth a special trip. Our other special experience of the trip was a tour of Dorset Nectar, a small, family-run organic cider farm just outside of Bridport, which included a tasting of their 10+ delicious ciders. We had splendid late-summer weather for our three days away, too – we really couldn’t have asked for better.

Three secondhand books purchased, for a total of £4.10.

Upcoming Reading Plans: Milan Trip and Summer Books

“Centre of fashion, business and finance,” “muggy and mosquito-ridden in summer” – from the guidebook descriptions it could hardly sound less like our kind of place, and yet Milan is where we’re off to tomorrow. While it wouldn’t be our first-choice destination, my husband is attending a landscape ecology conference there and presenting a paper; I’m going along for the week to have a holiday. It’s Italy. Why not?! I doubt the northern plain will be as much to our taste as Tuscany, which we explored on a wonderfully memorable trip in April 2014 (on which I first drank coffee), but there will still be history and culture around every corner, and we plan on eating very well and getting out of the city to see some of the Lakes region, too.

We’re traveling the slow way: a train to London; the Eurostar to Paris, where we’ll stay for one night; and a seven-hour train ride to Milan the following day. If the weather remains as hot as it has been in Continental Europe (e.g. 40°C / 105°F in Paris this week – ugh!), I’m not sure I’ll be up for a lot of solo sightseeing. I’ll put in a much-reduced work load for the week, but for much of the rest of the time when my husband is at the conference I may just lounge around our Airbnb, with a stack of print books, in front of the USB-powered fan I’ve ordered.

So of course I’ve been having great fun thinking about what reading material I might pack. I’ve assembled a main stack, and a subsidiary stack, of books that seem appropriate for one or more reasons.

Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell – To read on the Eurostar between London and Paris. Orwell’s first book and my first try with his nonfiction: an account of the living conditions of the poor in two world cities.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Classic of the month

Vintage 1954, Antoine Laurain – For a Nudge review; to read en route to and in Paris. Drinking a 1954 Beaujolais transports a Parisian and his neighbors – including an Airbnb guest – back to the 1950s. Sounds like good fun.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Lit in translation

The Great Railway Bazaar, Paul Theroux – To read on the long train ride to Milan. Theroux travels from London to Tokyo on trains, then returns via the Trans-Siberian Express. I’ve always meant to try his work.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Travel classics

Journey by Moonlight, Antal Szerb – A Hungarian novel set on an Italian honeymoon. Try to resist these first lines: “On the train everything seemed fine. The trouble began in Venice, with the back-alleys.”

Bonus goals it fulfills: Lit in translation; 20 Books of Summer substitute (horse on the cover)

The Awakening of Miss Prim, Natalia Sanmarin Fenollera – Promises to be a cozy, fluffy novel about what happens when librarian Prudencia Prim arrives in a small village. I had the feeling it was set in Italy, but maybe it’s actually Spain? I’ll find out.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Lit in translation

The Days of Abandonment, Elena Ferrante – I’ve tried two Ferrante novels and not been too impressed, yet still I keep trying. This one’s set during a heat wave. Maybe I’ll get on with it better than I did with My Brilliant Friend or The Lost Daughter?

Bonus goal it fulfills: Lit in translation

The extra stack:

Heat Wave, Penelope Lively – The title says it all.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Reading with the seasons

Barnacle Love, Anthony De Sa – An extra animal book for 20 Books of Summer.

Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell – A novel I’ve meant to read for years. I’ve earmarked it for our super-long day of travel back to the UK.

Bonus goal it fulfills: Doorstopper of the Month

Considering getting from the library:

The Last Supper, Rachel Cusk – I’ve only made it through one of the three Cusk books I’ve attempted, but perhaps a travel memoir is a more surefire selection?

On my Kindle:

The Fourth Shore, Virginia Baily – There’s an Italian flavor to this WWII novel, as there was to Baily’s previous one, Early One Morning. However, I’ve heard that this is mostly set in Tripoli, so I won’t make it a priority.

The Fourth Shore, Virginia Baily – There’s an Italian flavor to this WWII novel, as there was to Baily’s previous one, Early One Morning. However, I’ve heard that this is mostly set in Tripoli, so I won’t make it a priority.

From Scratch, Tembi Locke – An actress’s memoir of falling in love with an Italian chef and her trips to his family home in Sicily with their adopted daughter. (Foodie and bereavement themes!)

I’ll read the first few pages of lots of these to make sure they ‘take’ and will try to pack a sensible number. (Which probably means all but one or two!) We’ll be packing light in general, since there’s only so many clothes one can wear in such heat, so I don’t mind carrying a backpack full of books – I’m used to it from weekly treks to the library and flights to America, and I know that I don’t find reading on Kindle as satisfying, though it certainly is convenient for when you’re on the go.

If you’d like to put in a good word for any of the above options, or want to dissuade me from a book I might not find worthwhile, let me know.

Meanwhile, I’ve been slow out of the gate with my 20 Books of Summer, but I finally have a first set of mini-reviews coming up tomorrow.

Other summer-themed books that I have on hand or will get from the library soon include One Summer: America, 1927 by Bill Bryson, The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley, The Sun Does Shine by Anthony Ray Hinton, The Summer Book by Tove Jansson, and Sunburn by Laura Lippman.