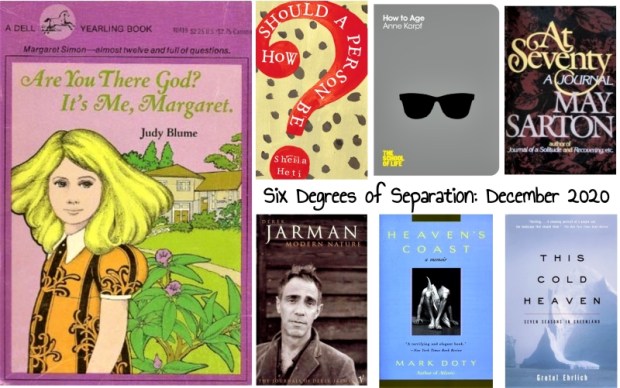

Six Degrees of Separation: From Margaret to This Cold Heaven

This month we’re starting with Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (which I have punctuated appropriately!). See Kate’s opening post. I know I read this as a child, but other Judy Blume novels were more meaningful for me since I was a tomboy and late bloomer. The only line that stays with me is the chant “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!”

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

A fitting final selection for this week’s properly chilly winter temperatures, too. I’ll be writing up my first snowy and/or holiday-themed reads of the year in a couple of weeks.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Adventures in Rereading: The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang

Last year I reviewed Tenth of December by George Saunders on its title date; this year I couldn’t resist rereading one of my favorites from 2014 for today’s date (which just so happens to be Bloomsday, made famous by James Joyce’s Ulysses), The Sixteenth of June.

I responded to the novel at length when it first came out. No point in reinventing the wheel, so here are mildly edited paragraphs of synopsis from my review for The Bookbag:

Maya Lang’s playful and exquisitely accomplished debut novel, set on the centenary of the original Bloomsday, transplants many characters and set pieces from Ulysses to near-contemporary Philadelphia. Don’t fret, though – even if, like me, you haven’t read Ulysses, you’ll have no trouble following the thread. In fact, Lang dedicates her book to “all the readers who never made it through Ulysses (or haven’t wanted to try).” (Though if you wish to spot parallels, pull up any online summary of Ulysses; there is also a page on Lang’s website listing her direct quotations from Joyce.)

Maya Lang’s playful and exquisitely accomplished debut novel, set on the centenary of the original Bloomsday, transplants many characters and set pieces from Ulysses to near-contemporary Philadelphia. Don’t fret, though – even if, like me, you haven’t read Ulysses, you’ll have no trouble following the thread. In fact, Lang dedicates her book to “all the readers who never made it through Ulysses (or haven’t wanted to try).” (Though if you wish to spot parallels, pull up any online summary of Ulysses; there is also a page on Lang’s website listing her direct quotations from Joyce.)

On June 16, 2004, brothers Leopold and Stephen Portman have two major commitments: their grandmother Hannah’s funeral is happening at the local synagogue in the morning; and their parents’ annual Bloomsday party will take place at their opulent Delancey Street home in the evening. Around those two thematic poles – the genuine emotions of grief and regret on the one hand, and the realm of superficial entertainment on the other – the novel expands outward to provide a nuanced picture of three ambivalent twenty-something lives.

The third side of this atypical love triangle is Nora, Stephen’s best friend from Yale – and Leo’s fiancée. Nora, a trained opera singer, is still reeling from her mother’s death from cancer one year ago. She’s been engaging in self-harming behavior, and Leo – a macho, literal-minded IT consultant – just wants to fix her. Nora and Stephen, by contrast, are sensitive, artistic souls who seem better suited to each other. Stephen, too, is struggling to find a meaning in death, but also to finish his languishing dissertation on Virginia Woolf.

Literature is almost as potent a marker of upper-class status as money here: some of the Portmans might not have even read Joyce’s masterpiece, but that doesn’t stop them name-dropping and maintaining the pretense of being well-read. While Lang might not mimic the extremes of Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness style, she prioritizes interiority over external action by using a close third-person voice that shifts between her main characters’ points of view. Their histories and thoughts are revealed mostly through interior monologues and conversations. Lang’s writing is full of mordant shards of humor; one of my favorite lines was “No one in a eulogy ever said, She watched TV with the volume on too loud.”

During my rereading, I was captivated more by the portraits of grief than by the subtle intellectual and class differences. I appreciated the characterization and the Joycean peekaboo, and the dialogue and shifts between perspectives still felt fresh and effortless. I could relate to Stephen and Nora’s feelings of being stuck and unsure how to move on in life. And the ending, which I’d completely forgotten, was perfect. I didn’t enjoy this quite as much the second time around, but it’s still a treasured signed copy on my shelf.

My original rating (June 2014):

My rating now:

Readalikes: Writers & Lovers by Lily King and The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud (my upcoming Doorstopper of the Month).

(See also my review of Lang’s recent memoir, What We Carry.)

Alas, I’ve also had a couple of failed rereading attempts recently…

Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer (2002)

I remembered this as a zany family history quest turned into fiction. A Jewish-American character named Jonathan Safran Foer travels to (fictional) Trachimbrod, Ukraine to find the traces of his ancestors and, specifically, the woman who hid his grandfather from the Nazis. I had totally forgotten about the comic narration via letters from Jonathan’s translator/tour guide, Alexander, who fancies himself a ladies’ man and whose English is full of comic thesaurus use (e.g. “Do not dub me that,” “Guilelessly yours”). This was amusing, but got to be a bit much. I’d also forgotten about the dense magic realism of the historical sections. As with A Visit from the Goon Squad, what felt dazzlingly clever on a first read (in January 2011) failed to capture me a second time. [35 pages]

I remembered this as a zany family history quest turned into fiction. A Jewish-American character named Jonathan Safran Foer travels to (fictional) Trachimbrod, Ukraine to find the traces of his ancestors and, specifically, the woman who hid his grandfather from the Nazis. I had totally forgotten about the comic narration via letters from Jonathan’s translator/tour guide, Alexander, who fancies himself a ladies’ man and whose English is full of comic thesaurus use (e.g. “Do not dub me that,” “Guilelessly yours”). This was amusing, but got to be a bit much. I’d also forgotten about the dense magic realism of the historical sections. As with A Visit from the Goon Squad, what felt dazzlingly clever on a first read (in January 2011) failed to capture me a second time. [35 pages]

Interestingly, Foer’s mother, Esther, released a memoir earlier this year, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here. It’s about the family history her son turned into quirky autofiction: a largely fruitless trip he took to Ukraine to research his maternal grandfather’s life for his Princeton thesis, and a more productive follow-up trip she took with her older son in 2009. Esther Safran Foer was born in Poland and lived in a German displaced persons camp until she and her parents emigrated to Washington, D.C. in 1949. Her father committed suicide in 1954, making him almost a belated victim of the Holocaust. The stories she hears in Ukraine – of the slaughter of entire communities; of moments of good luck that allowed her parents to, separately, survive and find each other – are remarkable, but the book’s prose, while capable, never sings. Plus, she references her son’s novel so often that I wondered why someone would read her book when they could read his instead.

Interestingly, Foer’s mother, Esther, released a memoir earlier this year, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here. It’s about the family history her son turned into quirky autofiction: a largely fruitless trip he took to Ukraine to research his maternal grandfather’s life for his Princeton thesis, and a more productive follow-up trip she took with her older son in 2009. Esther Safran Foer was born in Poland and lived in a German displaced persons camp until she and her parents emigrated to Washington, D.C. in 1949. Her father committed suicide in 1954, making him almost a belated victim of the Holocaust. The stories she hears in Ukraine – of the slaughter of entire communities; of moments of good luck that allowed her parents to, separately, survive and find each other – are remarkable, but the book’s prose, while capable, never sings. Plus, she references her son’s novel so often that I wondered why someone would read her book when they could read his instead.

On Beauty by Zadie Smith (2005)

This was an all-time favorite when it first came out. I remembered a sophisticated homage to E.M. Forster’s Howards End, featuring a biracial family in Cambridge, Mass. I remembered no specifics beyond a giant music store and (embarrassingly) an awkward sex scene. Howard Belsey’s long-distance rivalry with a fellow Rembrandt scholar gets personal when the Kipps family relocates from London to the Boston suburbs for Monty to be the new celebrity lecturer at the same college. Howard is in the doghouse with his African-American wife, Kiki, after having an affair. The Belsey boy and Kipps girl have an awkward romantic history. Zora Belsey is smitten with a lower-class spoken word poet she meets after a classical concert in the park when they pick up each other’s Discmans by accident (so dated!). All of the portraits felt like stereotypes to me, and there was so much telling, so much backstory, so many unnecessary secondary characters. Before I would have said this was my obvious Women’s Prize winner of winners, but now I have no idea what I’ll vote for. [107 pages]

This was an all-time favorite when it first came out. I remembered a sophisticated homage to E.M. Forster’s Howards End, featuring a biracial family in Cambridge, Mass. I remembered no specifics beyond a giant music store and (embarrassingly) an awkward sex scene. Howard Belsey’s long-distance rivalry with a fellow Rembrandt scholar gets personal when the Kipps family relocates from London to the Boston suburbs for Monty to be the new celebrity lecturer at the same college. Howard is in the doghouse with his African-American wife, Kiki, after having an affair. The Belsey boy and Kipps girl have an awkward romantic history. Zora Belsey is smitten with a lower-class spoken word poet she meets after a classical concert in the park when they pick up each other’s Discmans by accident (so dated!). All of the portraits felt like stereotypes to me, and there was so much telling, so much backstory, so many unnecessary secondary characters. Before I would have said this was my obvious Women’s Prize winner of winners, but now I have no idea what I’ll vote for. [107 pages]

Currently rereading: Watership Down by Richard Adams, Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn, Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama

To reread soon: Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty & Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara Kingsolver

Done any rereading lately?

Five Early March Releases: Jami Attenberg, Tayari Jones and More

Last week was one of the biggest weeks in the UK’s publishing year. Even though I’ve cut down drastically on the number of review books I’m receiving in 2020, I still had six on my shelf with release dates last week. Of course, THE biggest title out on the 5th was The Mirror and the Light, the final volume in Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell trilogy, which I’m eagerly awaiting from the library – I’m #3 in a holds queue of 34 people, but there are three copies, all showing as “Received at HQ,” so mine should come in any day now.

But for those who are immune to Mantel fever, or just seeking other material, there’s plenty to keep you busy. I give short reviews of five books today: a couple of dysfunctional family stories, two very different graphic novels and some feminist nonfiction.

All This Could Be Yours by Jami Attenberg

(Published by Serpent’s Tail on the 5th; came out in the USA from Houghton Mifflin in October)

Most of the action in Attenberg’s seventh book takes place on one day, as 73-year-old Victor Tuchman, struck down by a heart attack, lies on his deathbed in a New Orleans hospital. There’s more than a whiff of Trump about Victor, who has a shadowy mobster past and was recently hit with 11 sexual harassment charges. Forced to face the music for the first time, he fled Connecticut with his wife Barbra, citing the excuse of wanting to live closer to their son Gary in Louisiana. Victor had been abusive to Barbra throughout their marriage, and was just as violent in his speech: he could crush their daughter Alex with one remark on her weight.

So no one is particularly sad to see Victor dying. Alex goes through the motions of saying goodbye and telling her father she forgives him, knowing she doesn’t mean a word. Meanwhile, Gary is AWOL on a work trip to California, leaving his wife Twyla to take his place at Victor’s bedside. Twyla’s newfound piety is her penance for a dark secret that puts her at the heart of the family’s breakdown.

So no one is particularly sad to see Victor dying. Alex goes through the motions of saying goodbye and telling her father she forgives him, knowing she doesn’t mean a word. Meanwhile, Gary is AWOL on a work trip to California, leaving his wife Twyla to take his place at Victor’s bedside. Twyla’s newfound piety is her penance for a dark secret that puts her at the heart of the family’s breakdown.

Attenberg spends time with each family member on this long day supplemented by flashbacks, following Alex from bar to bar in downtown New Orleans as she tries to drown her sorrows and exploring other forms of addiction through Barbra (redecorating; not eating or ageing) and Twyla – in a particularly memorable scene, she heaps a shopping cart full of makeup at CVS and makes it all the way to the checkout before she snaps out of it. There’s also an interesting pattern of giving brief glimpses into the lives of the incidental characters whose paths cross with the family’s, including the EMT who took Victor to the hospital.

This is a timely tragicomedy, realistic and compassionate but also marked by a sardonic tone. Although readers only ever see Victor through other characters’ eyes, any smug sense of triumph they may feel about seeing the misbehaving, entitled male brought low is tempered by the extreme sadness of what happens to him after his death. I didn’t love this quite as much as The Middlesteins, but for me it’s a close second out of the four Attenberg novels I’ve read. She’s a real master of the dysfunctional family novel.

My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Silver Sparrow by Tayari Jones (2011)

(Published for the first time in the UK by Oneworld on the 5th)

Speaking of messed-up families … Growing up in 1980s Atlanta, Dana and Chaurisse both call James Witherspoon their father – but Chaurisse’s mother doesn’t even know that Dana exists. Dana’s mother, however, has always been aware of her husband’s other family. That didn’t stop her from agreeing to a quick marriage over the state line. Jones establishes James’s bigamy in the first line; the rest of the novel is mostly in two long sections, the first narrated by Dana and the second by Chaurisse. Both girls recount how their parents met, as well as giving a tour through their everyday life of high school and boyfriends.

Speaking of messed-up families … Growing up in 1980s Atlanta, Dana and Chaurisse both call James Witherspoon their father – but Chaurisse’s mother doesn’t even know that Dana exists. Dana’s mother, however, has always been aware of her husband’s other family. That didn’t stop her from agreeing to a quick marriage over the state line. Jones establishes James’s bigamy in the first line; the rest of the novel is mostly in two long sections, the first narrated by Dana and the second by Chaurisse. Both girls recount how their parents met, as well as giving a tour through their everyday life of high school and boyfriends.

I was eager to read this after enjoying Jones’s Women’s Prize winner, An American Marriage, so much. Initially I liked Dana’s narration as she elaborates on her hurt at being in a secret family. The scene where she unexpectedly runs into Chaurisse at a science fair and discovers their father bought them matching fur coats is a highlight. But by the midpoint the book starts to drag, and Chaurisse’s voice isn’t distinct enough for her narration to add much to the picture. A subtle, character-driven novel about jealousy and class differences, this failed to hold my interest. Alternating chapters from the two girls might have worked better?

My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

New graphic novels from SelfMadeHero:

The Mystic Lamb: Admired and Stolen by Harry De Paepe and Jan Van Der Veken

The Mystic Lamb: Admired and Stolen by Harry De Paepe and Jan Van Der Veken

[Translated by Albert Gomperts]

I’ve been to Ghent, Belgium twice. Any visitor will know that one of the city’s not-to-be-missed sights is the 15th-century altarpiece in St Bavo’s Cathedral, Jan van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. On our first trip we bought timed tickets to see this imposing and vibrantly colored multi-paneled artwork, which depicts various figures and events from the Bible as transplanted into a typically Dutch landscape. De Paepe gives a comprehensive account of the work’s nearly six-century history.

It’s been hidden during times of conflict or taken away as military spoils; it’s been split into parts and sold or stolen; it narrowly escaped a devastating fire. Overall, there was much more detail here than I needed, and far fewer illustrations than I expected. If you have a special interest in art history, you may well enjoy this. Just bear in mind that, although marketed as a graphic novel, it is mostly text.

Thoreau and Me by Cédric Taling

[Translated by Edward Gauvin]

I can’t seem to get away from Henry David Thoreau in my recent reading. Last year I reviewed for the TLS two memoirs that consciously appropriated the 19th-century environmentalist’s philosophy and language; the other night I found mentions of Thoreau in a Wallace Stegner novel, a new nature book by Lucy Jones, and travel books by Nancy Campbell and Charlie English. So I knew I had to read this debut graphic novel (but is it a memoir or autofiction?) about a Paris painter who is plagued by eco-anxiety and plans to build his own off-grid home in the woods.

I can’t seem to get away from Henry David Thoreau in my recent reading. Last year I reviewed for the TLS two memoirs that consciously appropriated the 19th-century environmentalist’s philosophy and language; the other night I found mentions of Thoreau in a Wallace Stegner novel, a new nature book by Lucy Jones, and travel books by Nancy Campbell and Charlie English. So I knew I had to read this debut graphic novel (but is it a memoir or autofiction?) about a Paris painter who is plagued by eco-anxiety and plans to build his own off-grid home in the woods.

Cédric and his middle-class friends are assailed by “white hipster guilt.” A brilliant sequence has a dinner party discussion descend into a cacophony of voices as they list the ethical minefields they face. Though Cédric wishes he were a prepared alpha male with advanced survival skills that could save his family, his main strategy seems to be panic buying cold-weather gear. Thoreau, depicted sometimes as a wolf or faun and always with a thin, tubular mosquito’s nose (like a Socratic gadfly?), comes to him as an invisible friend and guru, with quotes from Walden and his journal appearing in jagged speech bubbles. This was a good follow-up to Jenny Offill’s Weather with its themes of climate-related angst and perceived helplessness. I enjoyed the story even though I found the drawing style slightly grotesque.

My thanks to the publisher for the free copies for review.

And one extra:

The Home Stretch: Why It’s Time to Come Clean about Who Does the Dishes by Sally Howard

The Home Stretch: Why It’s Time to Come Clean about Who Does the Dishes by Sally Howard

(Published by Atlantic Books on the 5th)

I only gave this feminist book about the domestic labor gap a quick skim as, unfortunately, it repeats a lot of the examples and statistics that were familiar to me from works like Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Pérez (e.g. the Iceland women’s strike in the 1970s) and Fair Play by Eve Rodsky. The only chapter that stood out for me somewhat was about the “yummy mummy” stereotype perpetuated by the likes of Jools Oliver and Gwyneth Paltrow.

My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Review Books Roundup: Blackburn, Bryson, Pocock, Setterwall, Wilson

I’m attempting to get through all my 2019 review books before the end of the year, so expect another couple of these roundups. Today I’m featuring a work of poetry about one of Picasso’s mistresses, a thorough yet accessible introduction to how the human body works, a memoir of personal and environmental change in the American West, Scandinavian autofiction about the sudden loss of a partner, and a novel about kids who catch on fire. You can’t say I don’t read a variety! See if one or more of these tempts you.

The Woman Who Always Loved Picasso by Julia Blackburn

Something different from Blackburn: biographical snippets in verse about Marie-Thérèse Walter, one of Pablo Picasso’s many mistress-muses. When they met she was 17 and he was 46. She gave birth to a daughter, Maya – to his wife Olga’s fury. Marie-Thérèse’s existence was an open secret: he rented a Paris apartment for her to live in, and left his home in the South of France to her (where she committed suicide three years after his death), but unless their visits happened to overlap she was never introduced to his friends. “I lived in the time I was born into / and I kept silent, / acquiescing / to everything.”

Something different from Blackburn: biographical snippets in verse about Marie-Thérèse Walter, one of Pablo Picasso’s many mistress-muses. When they met she was 17 and he was 46. She gave birth to a daughter, Maya – to his wife Olga’s fury. Marie-Thérèse’s existence was an open secret: he rented a Paris apartment for her to live in, and left his home in the South of France to her (where she committed suicide three years after his death), but unless their visits happened to overlap she was never introduced to his friends. “I lived in the time I was born into / and I kept silent, / acquiescing / to everything.”

In Marie-Thérèse’s voice, Blackburn depicts Picasso as a fragile demagogue: in one of the poems that was a highlight for me, “Bird,” she describes how others would replace his caged birds when they died, hoping he wouldn’t notice – so great was his horror of death. I liked getting glimpses into a forgotten female’s life, and appreciated the whimsical illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher, but as poems these pieces don’t particularly stand out. (Plus, there are no page numbers! which doesn’t seem like it should make a big difference but ends up being annoying when you want to refer back to something. Instead, the poems are numbered.)

In Marie-Thérèse’s voice, Blackburn depicts Picasso as a fragile demagogue: in one of the poems that was a highlight for me, “Bird,” she describes how others would replace his caged birds when they died, hoping he wouldn’t notice – so great was his horror of death. I liked getting glimpses into a forgotten female’s life, and appreciated the whimsical illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher, but as poems these pieces don’t particularly stand out. (Plus, there are no page numbers! which doesn’t seem like it should make a big difference but ends up being annoying when you want to refer back to something. Instead, the poems are numbered.)

My rating:

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review. Published today.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson

Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction. Bryson is back on form here, indulging his layman’s curiosity. As you know, I read a LOT of medical memoirs and popular science. I’ve read entire books on organ transplantation, sleep, dementia, the blood, the heart, evolutionary defects, surgery and so on, but in many cases these go into more detail than I need and I can find my interest waning. That never happens here. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, the author gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system, moving briskly between engaging anecdotes from medical history and encapsulated research on everything from gut microbes to cancer treatment.

Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction. Bryson is back on form here, indulging his layman’s curiosity. As you know, I read a LOT of medical memoirs and popular science. I’ve read entire books on organ transplantation, sleep, dementia, the blood, the heart, evolutionary defects, surgery and so on, but in many cases these go into more detail than I need and I can find my interest waning. That never happens here. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, the author gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system, moving briskly between engaging anecdotes from medical history and encapsulated research on everything from gut microbes to cancer treatment.

Bryson delights in our physical oddities, and his sense of wonder is infectious. He loves a good statistic, and while this book is full of numbers and percentages, they are accessible rather than obfuscating, and will make you shake your head in amazement. It’s a persistently cheerful book, even when discussing illness, scientists whose work was overlooked, and the inevitability of death. Yet what I found most sobering was the observation that, having conquered many diseases and extended our life expectancy, we are now overwhelmingly killed by lifestyle, mostly a poor diet of processed and sugary foods and lack of exercise.

My rating:

With thanks to Doubleday for the free copy for review.

Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West by Joanna Pocock

Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. Then in her late forties, Pocock had started menopause and recently been through the final illnesses and deaths of her parents, but was also mother to a fairly young daughter. She explores personal endings and contradictions as a kind of microcosm of the paradoxes of the Western USA.

Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. Then in her late forties, Pocock had started menopause and recently been through the final illnesses and deaths of her parents, but was also mother to a fairly young daughter. She explores personal endings and contradictions as a kind of microcosm of the paradoxes of the Western USA.

It’s a place of fierce independence and conservatism, but also mystical back-to-the-land sentiment. For an outsider, so much of the lifestyle is bewildering. The author attends a wolf-trapping course, observes a Native American buffalo hunt, meets a transsexual rewilding activist, attends an ecosexuality conference, and goes foraging. All are attempts to reassess our connection with nature and ask what role humans can play in a diminished planet.

This is an elegantly introspective work that should engage anyone interested in women’s life writing and the environmental crisis. There are also dozens of black-and-white photographs interspersed in the text. In 2018 Pocock won the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize for this work-in-progress. It came to me as an unsolicited review copy and hung around on my shelves for six months before I picked it up; I’m glad I finally did.

My rating:

With thanks to Fitzcarraldo Editions for the free copy for review.

Let’s Hope for the Best by Carolina Setterwall

[Trans. from the Swedish by Elizabeth Clark Wessel]

Although this is fiction, it very closely resembles the author’s own life. She wrote this debut novel to reflect on the sudden loss of her partner and how she started to rebuild her life in the years that followed. It quickly splits into two parallel story lines: one begins in April 2009, when Carolina first met Aksel at a friend’s big summer bash; the other picks up in October 2014, after Aksel’s death from cardiac arrest. The latter proceeds slowly, painstakingly, to portray the aftermath of bereavement. In the alternating timeline, we see Carolina and Aksel making their life together, with her always being the one to push the relationship forward.

Although this is fiction, it very closely resembles the author’s own life. She wrote this debut novel to reflect on the sudden loss of her partner and how she started to rebuild her life in the years that followed. It quickly splits into two parallel story lines: one begins in April 2009, when Carolina first met Aksel at a friend’s big summer bash; the other picks up in October 2014, after Aksel’s death from cardiac arrest. The latter proceeds slowly, painstakingly, to portray the aftermath of bereavement. In the alternating timeline, we see Carolina and Aksel making their life together, with her always being the one to push the relationship forward.

Setterwall addresses the whole book in the second person to Aksel. When the two story lines meet at about the two-thirds point, it carries on into 2016 as she moves house, returns to work and resumes a tentative social life, even falling in love. This is a wrenching story reminiscent of In Every Moment We Are Still Alive by Tom Malmquist, and much of it resonated with my sister’s experience of widowhood. There are many painful moments that stick in the memory. Overall, though, I think it was too long by 100+ pages; in aiming for comprehensiveness, it lost some of its power. Page 273, for instance (the first anniversary of Aksel’s death, rather than the second, where the book actually ends), would have made a fine ending.

My rating:

With thanks to Bloomsbury UK for the proof copy for review.

Nothing to See Here by Kevin Wilson

I’d read a lot about this novel while writing a synopsis and summary of critical opinion for Bookmarks magazine – perhaps too much, as it felt familiar and offered no surprises. Lillian, a drifting twentysomething, is offered a job as a governess for her boarding school roommate Madison’s stepchildren. Madison’s husband is a Tennessee senator in the running for the Secretary of State position, so it’s imperative that they keep a lid on the situation with his 10-year-old twins, Bessie and Roland.

I’d read a lot about this novel while writing a synopsis and summary of critical opinion for Bookmarks magazine – perhaps too much, as it felt familiar and offered no surprises. Lillian, a drifting twentysomething, is offered a job as a governess for her boarding school roommate Madison’s stepchildren. Madison’s husband is a Tennessee senator in the running for the Secretary of State position, so it’s imperative that they keep a lid on the situation with his 10-year-old twins, Bessie and Roland.

You see, when they’re upset these children catch on fire; flames destroy their clothes and damage nearby soft furnishings, but leave the kids themselves unharmed. Temporary, generally innocuous spontaneous combustion? Okay. That’s the setup. Wilson writes so well that it’s easy to suspend your disbelief about this, but harder to see a larger point, except perhaps creating a general allegory for the challenges of parenting. This was entertaining enough, mostly thanks to Lillian’s no-nonsense narration, but for me it didn’t soar.

My rating:

With thanks to Text Publishing UK for the PDF for review. This came out in the States in October and will be released in the UK on January 30th.

The first section, “After,” responds to the events of 2020; six of its poems were part of a “Twelve Days of Lockdown” commission. Fox remembers how sinister a cougher at a public event felt on 13th March and remarks on how quickly social distancing came to feel like the norm, though hikes and wild swimming helped her to retain a sense of possibility. I especially liked “Pharmacopoeia,” which opens the collection and looks back to the Black Death that hit Amsterdam in 1635 – “suddenly the plagues / are the most interesting parts / of a city’s history.” “Returns” plots her next trip to a bookshop (“The plague books won’t be in yet, / but the dystopia section will be well stocked / … I spend fifty pounds I no longer had last time, will spend another fifty next. / Feeling I’m preserving an ecology, a sort of home”), while “The Funerals” wryly sings the glories of a spring the deceased didn’t get to see.

The first section, “After,” responds to the events of 2020; six of its poems were part of a “Twelve Days of Lockdown” commission. Fox remembers how sinister a cougher at a public event felt on 13th March and remarks on how quickly social distancing came to feel like the norm, though hikes and wild swimming helped her to retain a sense of possibility. I especially liked “Pharmacopoeia,” which opens the collection and looks back to the Black Death that hit Amsterdam in 1635 – “suddenly the plagues / are the most interesting parts / of a city’s history.” “Returns” plots her next trip to a bookshop (“The plague books won’t be in yet, / but the dystopia section will be well stocked / … I spend fifty pounds I no longer had last time, will spend another fifty next. / Feeling I’m preserving an ecology, a sort of home”), while “The Funerals” wryly sings the glories of a spring the deceased didn’t get to see. For instance, “The Grass Widower,” while his wife is away visiting her mother, indulges his love of seafood and learns how to wash up effectively. A convalescent plans the uncomplicated meals she’ll fix, including lots of egg dishes and some pleasingly dated fare like “junket” and cherries in brandy. A brother and sister, students left on their own for a day, try out all the different pancakes and quick breads in their repertoire. The bulk of the actual meal ideas come in a chapter called “The Happy Potterer,” whom Le Riche styles as a friend of hers named Flora who wrote out all her recipes on cards collected in an envelope. I enjoyed some of the little notes to self in this section: appended to a recipe for kidney and mushrooms, “Keep a few back for mushrooms-on-toast next day for a mid-morning snack”; “Forgive yourself if you have to use margarine instead of butter for frying.”

For instance, “The Grass Widower,” while his wife is away visiting her mother, indulges his love of seafood and learns how to wash up effectively. A convalescent plans the uncomplicated meals she’ll fix, including lots of egg dishes and some pleasingly dated fare like “junket” and cherries in brandy. A brother and sister, students left on their own for a day, try out all the different pancakes and quick breads in their repertoire. The bulk of the actual meal ideas come in a chapter called “The Happy Potterer,” whom Le Riche styles as a friend of hers named Flora who wrote out all her recipes on cards collected in an envelope. I enjoyed some of the little notes to self in this section: appended to a recipe for kidney and mushrooms, “Keep a few back for mushrooms-on-toast next day for a mid-morning snack”; “Forgive yourself if you have to use margarine instead of butter for frying.” Chang and Christa, the subjects of the book’s first two sections – accounting for about half the length – were opposites and had a volatile relationship. Their home in the New York City projects was an argumentative place the narrator was eager to escape. She felt she never knew her father, a humourless man who lost touch with Chinese culture. He worked on the kitchen staff of a hospital and never learned English properly. Christa, by contrast, was fastidious about English grammar but never lost her thick accent. An obstinate and contradictory woman, she resented her lot in life and never truly loved Chang, but was good with her hands and loved baking and sewing for her daughters.

Chang and Christa, the subjects of the book’s first two sections – accounting for about half the length – were opposites and had a volatile relationship. Their home in the New York City projects was an argumentative place the narrator was eager to escape. She felt she never knew her father, a humourless man who lost touch with Chinese culture. He worked on the kitchen staff of a hospital and never learned English properly. Christa, by contrast, was fastidious about English grammar but never lost her thick accent. An obstinate and contradictory woman, she resented her lot in life and never truly loved Chang, but was good with her hands and loved baking and sewing for her daughters. Thammavongsa pivoted from poetry to short stories and won Canada’s Giller Prize for this debut collection that mostly explores the lives of Laotian immigrants and refugees in a North American city. The 14 stories are split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, many of them narrated by young women remembering how they and their parents adjusted to an utterly foreign culture. The title story and “Chick-A-Chee!” are both built around a misunderstanding of the English language – the latter is a father’s approximation of what his children should say on doorsteps on Halloween. Television soaps and country music on the radio are ways to pick up more of the language. Farm and factory work are de rigueur, but characters nurture dreams of experiences beyond menial labour – at least for their children.

Thammavongsa pivoted from poetry to short stories and won Canada’s Giller Prize for this debut collection that mostly explores the lives of Laotian immigrants and refugees in a North American city. The 14 stories are split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, many of them narrated by young women remembering how they and their parents adjusted to an utterly foreign culture. The title story and “Chick-A-Chee!” are both built around a misunderstanding of the English language – the latter is a father’s approximation of what his children should say on doorsteps on Halloween. Television soaps and country music on the radio are ways to pick up more of the language. Farm and factory work are de rigueur, but characters nurture dreams of experiences beyond menial labour – at least for their children.

Kika & Me by Amit Patel – Patel was a trauma doctor and lost his sight within 36 hours due to a rare condition. He was paired with his guide dog, Kika, in 2015.

Kika & Me by Amit Patel – Patel was a trauma doctor and lost his sight within 36 hours due to a rare condition. He was paired with his guide dog, Kika, in 2015. Water is a source of comfort and delight for Abi, the narrator of Sanatorium (whose experiences may or may not be those of the author; always tricky to tell with autofiction). Floating is like dreaming for her – an intermediate state between the solid world where she’s in pain and the prospect of vanishing into the air. In 2017 she spends a few weeks at a sanatorium in Budapest for water therapy; when she returns to London she buys a big inflatable plastic bathtub to keep up the exercises as she tries to wean herself off of opiates.

Water is a source of comfort and delight for Abi, the narrator of Sanatorium (whose experiences may or may not be those of the author; always tricky to tell with autofiction). Floating is like dreaming for her – an intermediate state between the solid world where she’s in pain and the prospect of vanishing into the air. In 2017 she spends a few weeks at a sanatorium in Budapest for water therapy; when she returns to London she buys a big inflatable plastic bathtub to keep up the exercises as she tries to wean herself off of opiates. The book is in snippets, often of just a paragraph or even one sentence, and cycles through its several strands: Abi’s time in Budapest and how she captures it in an audio diary; ongoing therapy at her London flat, custom-designed for disabled tenants (except “I was the only cripple who could afford it”); the haunted house she grew up in in Surrey; and notes on plus prayers to St. Teresa of Ávila, accompanied by diagrams of a female figure in yoga poses.

The book is in snippets, often of just a paragraph or even one sentence, and cycles through its several strands: Abi’s time in Budapest and how she captures it in an audio diary; ongoing therapy at her London flat, custom-designed for disabled tenants (except “I was the only cripple who could afford it”); the haunted house she grew up in in Surrey; and notes on plus prayers to St. Teresa of Ávila, accompanied by diagrams of a female figure in yoga poses.

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after  I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read ( In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.  Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.

Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.  February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her. Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

As in

As in  Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with  The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.

The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen. Stella, Kay, Helena, Polly and Priss met at a picnic while studying at Oxbridge and decided to rent a house together. Now 40-ish, they live in London and remain close, though their lives have branched in slightly different directions. Kay is an English teacher but has always wanted to be a novelist like her American husband, Harald. Priss is a stay-at-home mother excited to be opening a café. Polly, a gynaecological consultant at St Thomas’s Hospital, is having an affair with a married colleague. Helena, a single documentary presenter, decides she wants to have a baby and pursues insemination via a gay friend.

Stella, Kay, Helena, Polly and Priss met at a picnic while studying at Oxbridge and decided to rent a house together. Now 40-ish, they live in London and remain close, though their lives have branched in slightly different directions. Kay is an English teacher but has always wanted to be a novelist like her American husband, Harald. Priss is a stay-at-home mother excited to be opening a café. Polly, a gynaecological consultant at St Thomas’s Hospital, is having an affair with a married colleague. Helena, a single documentary presenter, decides she wants to have a baby and pursues insemination via a gay friend.

McCarthy focuses on eight girls from the Vassar class of ’33. Kay, the first to marry, has an upper-crust New York City wedding one week after graduation. But after Harald loses his theatre job, his cocktail habit and their luxury apartment soon deplete Kay’s Macy’s salary. Meanwhile, Dottie loses her virginity to Harald’s former neighbour in a surprisingly explicit scene. Contraception is complicated, but not without comic potential – as when Dottie confuses a pessary and a peccary. Career, romance, and motherhood are all fraught matters.

McCarthy focuses on eight girls from the Vassar class of ’33. Kay, the first to marry, has an upper-crust New York City wedding one week after graduation. But after Harald loses his theatre job, his cocktail habit and their luxury apartment soon deplete Kay’s Macy’s salary. Meanwhile, Dottie loses her virginity to Harald’s former neighbour in a surprisingly explicit scene. Contraception is complicated, but not without comic potential – as when Dottie confuses a pessary and a peccary. Career, romance, and motherhood are all fraught matters. Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s

Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s  These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of

These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of  Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder.

Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder. Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires.

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires. With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.