Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

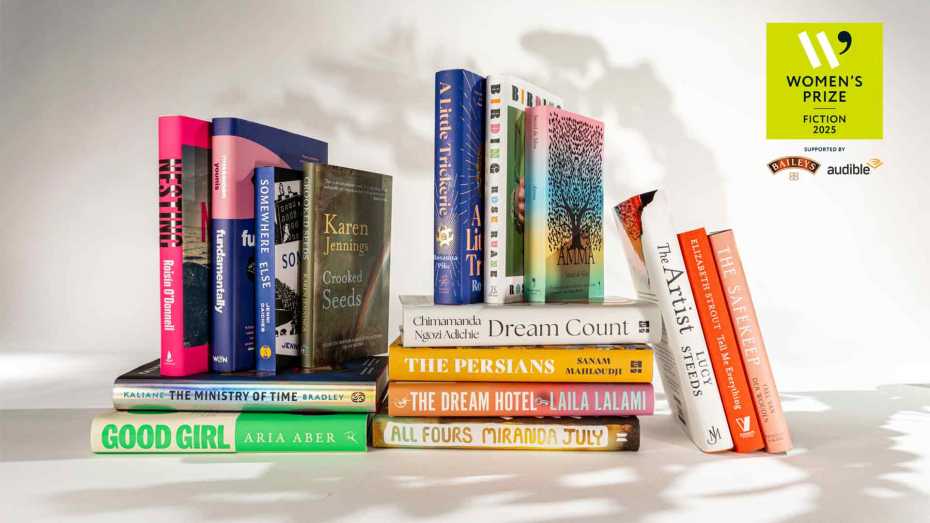

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Literary Wives Club: His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

(My fourth read with the Literary Wives online book club; see also Kay’s review and Naomi’s review.)

{SPOILERS IN THIS ONE}

Peace Adzo Medie’s 2020 debut novel was the first disappointment I’ve had from Reese Witherspoon’s book club. The Kirkus review excerpt inside the paperback’s front cover should have given me an idea of what to expect: “A Cinderella story set in Ghana … A Crazy Rich Asians for West Africa.” While both slightly reductive, those comparisons do give some sense of the book’s tone and superficiality.

Afi Tekple is a seamstress whose family arranges for her to marry Elikem Ganyo, a rich international businessman who has properties all over Ghana. In a neat bit of symmetry, I read a novel earlier this year that opened with a traditional Ghanaian divorce ceremony where the husband was in absentia (What Napoleon Could Not Do); this opens with a traditional wedding ceremony where, again, the groom isn’t there. The giving of schnapps as part of a dowry is a customary element of both.

The first half of the novel was agonizingly slow. Afi and her mother do little but sit in an opulent Accra flat, waiting for Eli to grace them with his presence. When he does appear, what luck! (eye roll) he and Afi have a magical sexual connection, described in romance novel language. But he’s only there part time, dividing his attentions between households. Afi enrols in fashion school, cooks and keeps house for Eli, and falls pregnant with his son, Selorm. (In another instance of poor pacing, we then jump to a year after the birth.) It should be a perfect life, yet she’s not happy because there is a rival for her husband’s affections.

You see, Eli’s family chose Afi in the hope that she’d get him to give up the Liberian woman who gave birth to his sickly daughter. They despise Muna for her independent spirit and transgressive behaviour. Although Afi knew about Muna, she doesn’t realize the extent to which she was the Ganyos’ pawn until late on. Meanwhile, Afi has gone from a timid country girl to a confident, high-class boutique owner accustomed to modern conveniences. She won’t ignore her longing to move into Eli’s house and get their marriage legally recognized. She issues an ultimatum: either she’s the only, official wife or she’s out of there.

I kept expecting a showdown between Afi and Muna; then, the further I got, the more I feared Muna wouldn’t appear at all. She does have a scene, 20 pages from the end, and instantly takes on more contours than the evil stereotype the Ganyos have spread, yet it doesn’t change Afi’s jealousy and determination to live independently. I hoped for more of a message of understanding and sisterhood. Initially, the arranged marriage plot reminded me of a particular Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie short story, but Afi’s narration was only so-so and there were more grammar and vocabulary errors than I’m used to encountering in conventionally published work. This might appeal to readers of Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me. (Public library)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

My main takeaway from His Only Wife is that a marriage doesn’t work if there’s someone interfering – and that refers to Afi’s mother-in-law probably more so than it does to Muna.

Eli just wants to have his cake and eat it. He thinks he should be free to accumulate as many cars and houses and women as he wants. He never intended to leave that woman and you all knew it … I want him to be mine only. Is that too much to ask? I’m sorry that I’m not like other wives who are able to happily share their husbands with co-wives and mistresses and girlfriends. That’s just not me. I’m not built like that.

I was a little uncomfortable that Medie presents legal marriage and monogamy as the only viable option, with Afi coming to disparage the village ceremony she had and wanting the fairy tale proposal in Paris and church wedding instead. Polygamy has a long tradition in countries including Ghana and Nigeria; it might have been interesting for Medie to explore contrasting attitudes toward it. Instead, this feels like pandering to Western tastes.

Next book: The Harpy by Megan Hunter in June

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research?

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research? The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project.

The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project. The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund. New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

The best of the lot, though, has been Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana, which I’ll be reviewing for BookBrowse over the weekend. It’s a character- and voice-driven set of eight stories about the residents of a Harlem apartment complex, many of them lovable rogues who have to hustle to try to make rent in this gentrifying area.

The best of the lot, though, has been Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana, which I’ll be reviewing for BookBrowse over the weekend. It’s a character- and voice-driven set of eight stories about the residents of a Harlem apartment complex, many of them lovable rogues who have to hustle to try to make rent in this gentrifying area.

A September release I’ll quickly plug: The Best Short Stories 2022: The O. Henry Prize Winners, selected by Valeria Luiselli. I read this for Shelf Awareness and my review will be appearing in a couple of weeks. Half of the 20 stories are in translation – Luiselli insists this was coincidental – so it’s a nice taster of international short fiction. Contributing authors you will have heard of: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lorrie Moore, Samanta Schweblin and Olga Tokarczuk. The style runs the gamut from metafiction to sci-fi/horror. Covid-19, loss and parenting are frequent elements. My two favourites: Joseph O’Neill’s “Rainbows,” about sexual misconduct allegations, then and now; and the absolutely bonkers novella-length “Horse Soup” by Vladimir Sorokin, about a woman and a released prisoner who meet on a train and bond over food. (13 September, Anchor Books)

A September release I’ll quickly plug: The Best Short Stories 2022: The O. Henry Prize Winners, selected by Valeria Luiselli. I read this for Shelf Awareness and my review will be appearing in a couple of weeks. Half of the 20 stories are in translation – Luiselli insists this was coincidental – so it’s a nice taster of international short fiction. Contributing authors you will have heard of: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lorrie Moore, Samanta Schweblin and Olga Tokarczuk. The style runs the gamut from metafiction to sci-fi/horror. Covid-19, loss and parenting are frequent elements. My two favourites: Joseph O’Neill’s “Rainbows,” about sexual misconduct allegations, then and now; and the absolutely bonkers novella-length “Horse Soup” by Vladimir Sorokin, about a woman and a released prisoner who meet on a train and bond over food. (13 September, Anchor Books)  Here’s a short story collection I received for review but, alas, couldn’t finish: Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. This was longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize and won the NB Magazine Blogger’s Book Prize. The link, I have gathered, is adolescent girls in Florida. I enjoyed the title story, which opens the collection and takes peer pressure and imitation to an extreme, but couldn’t get through more than another 1.5 after that; they left zero impression.

Here’s a short story collection I received for review but, alas, couldn’t finish: Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. This was longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize and won the NB Magazine Blogger’s Book Prize. The link, I have gathered, is adolescent girls in Florida. I enjoyed the title story, which opens the collection and takes peer pressure and imitation to an extreme, but couldn’t get through more than another 1.5 after that; they left zero impression. Resuming soon: The Predatory Animal Ball by Jennifer Fliss (e-book), Hearts & Bones by Niamh Mulvey, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw – all were review copies.

Resuming soon: The Predatory Animal Ball by Jennifer Fliss (e-book), Hearts & Bones by Niamh Mulvey, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw – all were review copies. This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed

This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on

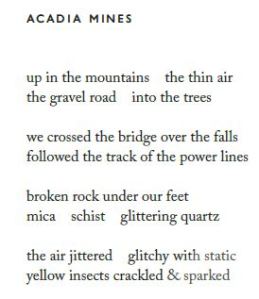

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on  Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after