20 Books of Summer, 9–10: Leave the World Behind & Leaving Atlanta

Halfway there! And I’m doing better than it might appear in that I’m in the middle of another 7 books and just have to decide what the final 3 will be. This was a sobering but satisfying pair of novels in which race and class play a part but the characters are ultimately helpless in the face of disasters and violence. Both: ![]()

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam (2020)

The title heralds a perfect holiday read, right? A New York City couple, Amanda and Clay, have rented a secluded vacation home in Long Island with their teenagers, Archie and Rose, and plan on a week of great beach weather and mild hedonism: food, drink, secret cigarettes, a hot tub, maybe some sex. But late on the first night there’s a knock on the door from the owners, sixtysomething Black couple Ruth and G. H. Something is going on; although the house still has power, all phone and Internet services have gone down. Rather than return to a potentially chaotic city, the older couple set course for their country retreat to hunker down. George is in finance and believes money solves everything, so he offers Amanda and Clay $1000 cash for the inconvenience of having their holiday interrupted.

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

This was a book club read and one of the most divisive I can remember. I was among the few who thought it gripping, intriguing, and even genuinely frightening. Others found the characters unlikable, the plot implausible or silly, and the writing heavy-handed. Alam is definitely poking fun at privileged bougie families. He draws attention to the author as puppet-master, inserting shrewd hints of what is occurring elsewhere or will soon befall certain characters. Some passages skirt pomposity with their anaphora and rhetorical questioning. Alliteration, repetition, and stark pronouncements make the prose almost baroque in places. Alam’s style is theatrical, even arch, but it suits the premonitory tone. I admired how he constantly upends genre expectations, moving from literary fiction to domestic drama to dystopia to magic realism to horror. The stuff of nightmares – being naked in front of strangers, one’s teeth falling out – becomes real, or at least real in the world of the book. The reminder is that we are never as in control as we think we are; always, disasters are unfolding. What will we do, and who will we be, as the inevitable unfolds?

You demanded answers, but the universe refused. Comfort and safety were just an illusion. Money meant nothing. All that meant anything was this—people, in the same place, together. This was what was left to them.

Absorbing, timely, controversial: read it! (Free from a neighbour)

Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones (2002)

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Even as their school is making news headlines, the children’s concerns are perennial adolescent ones: how to avoid bullying, who to sit with at lunch, how to be friendly yet not falsely encourage members of the opposite sex. And at home, all three struggle with an absent or overbearing father. At age 11, these kids are just starting to realize that their parents aren’t perfect and might not be able to keep them safe. I especially warmed to Octavia’s voice, even as her story made my heart ache: “cussing at myself for being too stupid to see that nothing lasts. That people get away from you like a handful of sweet smoke.” I preferred this offbeat, tender coming-of-age novel to Silver Sparrow and would place it on a par with An American Marriage. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

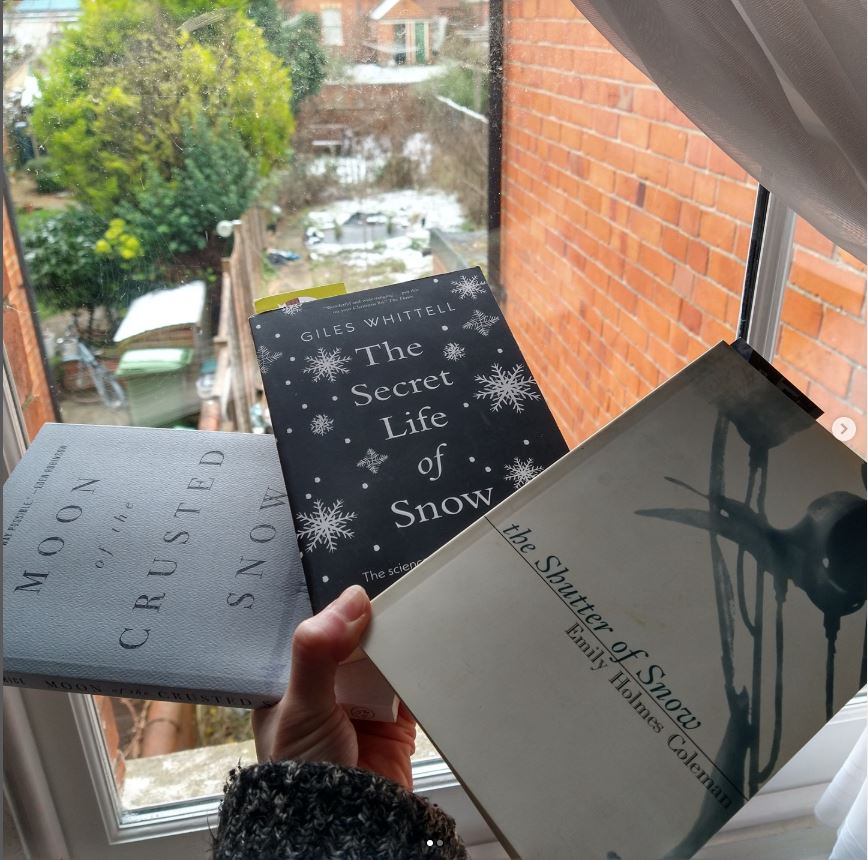

Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

#SciFiMonth: A Simple Intervention (#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth) & Station Eleven Reread

It’s rare for me to pick up a work of science fiction but occasionally I’ll find a book that hits the sweet spot between literary fiction and sci-fi. Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell are a few prime examples. It was the comparisons to Margaret Atwood and Kazuo Ishiguro, masters of the speculative, that drew me to my first selection, a Peirene Press novella. My second was a reread, 10 years on, for book club, whose postapocalyptic content felt strangely appropriate for a week that delivered cataclysmic election results.

A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai (2022; 2024)

[Translated from the German by Marielle Sutherland]

Meret is a nurse on a surgical ward, content in the knowledge that she’s making a difference. Her hospital offers a pioneering procedure that cures people of mental illnesses. It’s painless and takes just an hour.

The doctor had to find the affected area and put it to sleep, like a sick animal. That was his job. Mine was to keep the patients occupied. I was to distract them from what was happening and keep them interacting with me. As long as they stayed awake, we knew the doctor and his instruments had found the right place.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

Inokai invites us to ponder whether what we perceive as defects are actually valuable personality traits. More examples of interventions and their aftermath would be a useful point of comparison, though, and the pace is uneven, with a lot of unnecessary-seeming backstory about Meret’s family life. In the letter that accompanied my review copy, Inokai explained her three aims: to portray a nurse (her mother’s career) because they’re underrepresented in fiction, “to explore our yearning to cut out our ‘demons’,” and to offer “a queer love story that was hopeful.” She certainly succeeds with those first and third goals, but with the central subject I felt she faltered through vagueness.

Born in Switzerland, Inokai now lives in Berlin. This also counts as my first contribution to German Literature Month; another is on the way!

[187 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

For synopsis and analysis I can’t do better than when I reviewed this for BookBrowse a few months after its release, so I’d direct you to the full text here. (It’s slightly depressing for me to go back to old reviews and see that I haven’t improved; if anything, I’ve gotten lazier.) A couple book club members weren’t as keen, I think because they’d read a lot of dystopian fiction or seen many postapocalyptic films and found this vision mild and with a somewhat implausible setup and tidy conclusion. But for me this and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road have persisted as THE literary depictions of post-apocalypse life because they perfectly blend the literary and the speculative in an accessible and believable way (this was a National Book Award finalist and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award), contrasting a harrowing future with nostalgia for an everyday life that we can already see retreating into the past.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

The two themes that most struck me this time were the enduring power of art and how societal breakdown would instantly eliminate the international – but compensate for it with the return of the extremely local. At a time when it feels difficult to trust central governments to have people’s best interests at heart, this is a rather comforting prospect. Just in my neighbourhood, I see how we implement this care on a small scale. In settlements of up to a few hundred, the remnants of Station Eleven create something like normal life by Year 20.

Book club members sniped that the characters could have better pooled skills, but we agreed that Mandel was wise to limit what could have been tedious details about survival. “Survival is insufficient,” as the Traveling Symphony’s motto goes (borrowed from Star Trek). Instead, she focuses on love, memory, and hunger for the arts. In some ways, this feels prescient of Covid-19, but even more so of the climate-related collapse I expect in my lifetime. I’ve rated this a little bit higher the second time for its lasting relevance. (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

Some favourite passages:

the whole of Chapter 6, a bittersweet litany that opens “An incomplete list: No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below” and includes “No more pharmaceuticals,” “No more flight,” and “No more countries”

“what made it bearable were the friendships, of course, the camaraderie and the music and the Shakespeare, the moments of transcendent beauty and joy”

“The beauty of this world where almost everyone was gone. If hell is other people, what is a world with almost no people in it?”

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

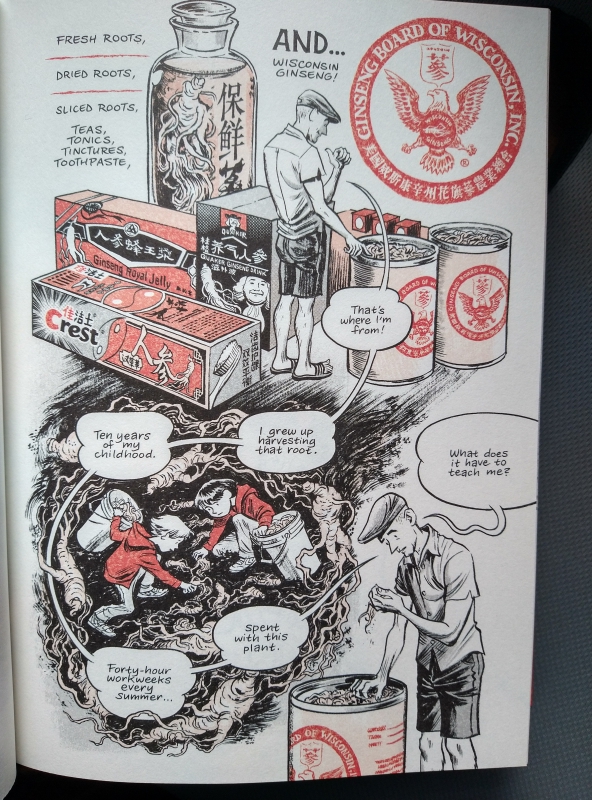

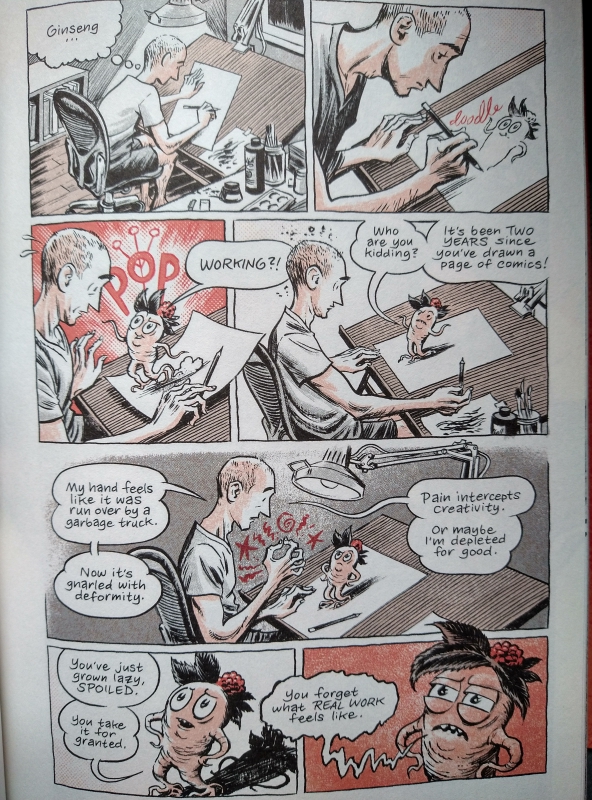

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot. A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

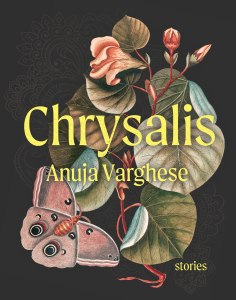

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age. In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).