The Party by Tessa Hadley (Blog Tour and #NovNov24)

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

The novella’s three chapters each revolve around a party. First is the Bristol dockside pub party (published as a short story in the New Yorker); second is a cocktail party the girls’ parents are preparing for, giving us a window onto their troubled marriage; finally is a gathering Paul invites them to at the shabby inherited mansion he lives in with his cousin, invalid brother, and louche sister. “We camp in it like kids,” Paul says. “Just playing at being grown up, you know.” During their night spent at the mansion, the sisters become painfully aware of the class difference between them and Paul’s moneyed family. The divide between innocence and experience may be sharp, but the line between love and hatred is not always as clear as they expected. And from moments of decision all the rest of life flows.

In her novels and story collections, Hadley often writes about strained families, young women on the edge, and the way sex can force a change in direction. This was my eighth time reading her, and though The Party is as stylish as all her work, it didn’t particularly stand out for me, lacking the depth of her novels and the concentration of her stories. Still, it would be a good introduction to Hadley or, if you’re an established fan like me, you could read it in a sitting and be reminded of her sharp eye for manners and pretensions – and the emotions they mask.

[115 pages]

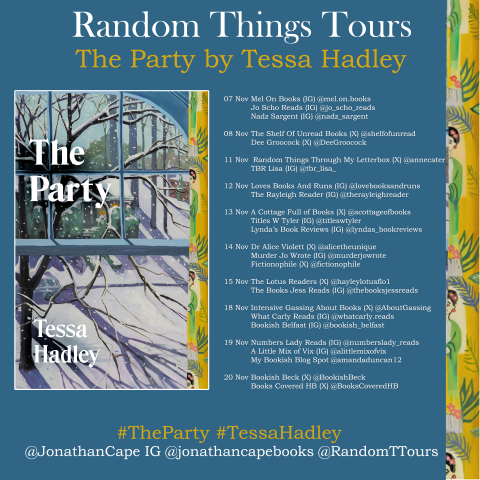

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Party from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Party. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

Astraea by Kate Kruimink (Weatherglass Novella Prize) #NovNov24

Astraea by Kate Kruimink is one of two winners* of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. Back in September, I was introduced to it through Weatherglass Books’ “The Future of the Novella” event in London (my write-up is here).

Taking place within about a day and a half on a 19th-century convict ship bound for Australia, it is the intense story of a group of women and children chafing against the constraints men have set for them. The protagonist is just 15 years old and postpartum. Within a hostile environment, the women have created an almost cosy community based on sisterhood. They look out for each other; an old midwife can still bestow her skills.

The ship was their shelter, the small chalice carrying them through that which was inhospitable to human life. But there was no shelter for her there, she thought. There was only a series of confines between which she might move but never escape.

The ship’s doctor and chaplain distrust what they call the “conspiracy of women” and are embarrassed by the bodily reality of one going into labour, another tending to an ill baby, and a third haemorrhaging. They have no doubt they know what is best for their charges yet can barely be bothered to learn their names.

Indeed, naming is key here. The main character is effectively erased from the historical record when a clerk incorrectly documents her as Maryanne Maginn. Maryanne’s only “maybe-friend,” red-haired Sarah, has the surname Ward. “Astraea” is the name not just of the ship they travel on but also of a star goddess and a new baby onboard.

The drama in this novella arises from the women’s attempts to assert their autonomy. Female rage and rebellion meet with punishment, including a memorable scene of solitary confinement. A carpenter then constructs a “nice little locking box that will hold you when you sin, until you’re sorry for it and your souls are much recovered,” as he tells the women. They are all convicts, and now their discipline will become a matter of religious theatrics.

Given the limitations of setting and time and the preponderance of dialogue, I could imagine this making a powerful play. The novella length is as useful a framework as the ship itself. Kruimink doesn’t waste time on backstory; what matters is not what these women have done to end up here, but how their treatment is an affront to their essential dignity. Even in such a low page count, though, there are intriguing traces of the past and future, as well as a fleeting hint of homoeroticism. I would recommend this to readers of The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, Devotion by Hannah Kent and Women Talking by Miriam Toews. And if you get a hankering to follow up on the story, you can: this functions as a prequel to Kruimink’s first novel, A Treacherous Country. (See also Cathy’s review.)

[115 pages]

With thanks to Weatherglass Books for the free copy for review.

*The other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths, will be published in January. I hope to have a proof copy in hand before the end of the month to review for this challenge plus SciFi Month.

My Year in Novellas (#NovNov24)

Here at the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about the novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a special shelf of short books that I add to throughout the year. When at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, a Little Free Library, or the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about my piles for November. But I do read novellas at other times of year, too. Forty-four of them between December 2023 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year it was 46, so it seems like that’s par for the course). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My favourites of the ones I’ve already covered on the blog would probably be (nonfiction) Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti and (fiction) Aimez-vous Brahms by Françoise Sagan. My proudest achievements are: reading the short graphic novel Broderies by Marjane Satrapi in the original French at our Parisian Airbnb in December; and managing two rereads: Heartburn by Nora Ephron and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Of the short books I haven’t already reviewed here, I’ve chosen two gems, one fiction and one nonfiction, to spotlight in this post:

Fiction

Clear by Carys Davies

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

In my book club, opinions differed slightly as to the central relationship and the conclusion, but we agreed that it was beautifully done, with so much conveyed in the concise length. This received our highest rating ever, in fact. I’d read Davies’ West and not appreciated it as much, although looking back I can see that it was very similar: one or a few character(s) embarked on unusual and intense journey(s); a plucky female character; a heavy sense of threat; and an improbably happy ending. It was the ending that seemed to come out of nowhere and wasn’t in keeping with the tone of the rest of the novella that made me mark West down. Here I found the writing cinematic and particularly enjoyed Mary as a strong character who escaped spinsterhood but even in marriage blazes her own trail and is clever and creative enough to imagine a new living situation. And although the ending is sudden and surprising, it nevertheless seems to arise naturally from what we know of the characters’ emotional development – but also sent me scurrying back to check whether there had been hints. One of my books of the year for sure. ![]()

Nonfiction

A Termination by Honor Moore

Poet and memoirist Honor Moore’s A Termination is a fascinatingly discursive memoir that circles her 1969 abortion and contrasts societal mores across her lifetime.

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

Family and social factors put Moore’s experiences into perspective. The first doctor she saw refused Moore’s contraception request because she was unmarried. Her mother, however, bore nine children and declined to abort a pregnancy when advised to do so for medical reasons. Moore observes that she made her own decision almost 10 years before “the word choice replaced pro abortion.”

This concise work is composed of crystalline fragments. The stream of consciousness moves back and forth in time, incorporating occasional second- and third-person narration as well as highbrow art and literature references. Moore writes one scene as if it’s in a play and imagines alternative scenarios in which she has a son; though she is curious, she is not remorseful. The granular attention to women’s lives recalls Annie Ernaux, while the kaleidoscopic yet fluid approach is reminiscent of Sigrid Nunez’s work. It’s a stunning rendering of steps on her childfree path. ![]()

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I currently have four novellas underway and plan to start some more this weekend. I have plenty to choose from!

Everyone’s getting in on the act: there’s an article on ‘short and sweet books’ in the November/December issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I’m an associate editor; Goodreads sent around their usual e-mail linking to a list of 100 books under 250 or 200 pages to help readers meet their 2024 goal. Or maybe you’d like to join in with Wafer Thin Books’ November buddy read, the Ugandan novella Waiting by Goretti Kyomuhendo (2007).

Why not share some recent favourite novellas with us in a post of your own?

R.I.P., Part II: Duy Đoàn, T. Kingfisher & Rachael Smith

A second installment for the Readers Imbibing Peril challenge (first was a creepy short story collection). Zombies link my first two selections, an experimental poetry collection and a historical novella that updates a classic, followed by a YA graphic novel about a medieval witch who appears in contemporary life to help a teen deal with her problems. I don’t really do proper horror; I’d characterize all three of these as more mischievous than scary.

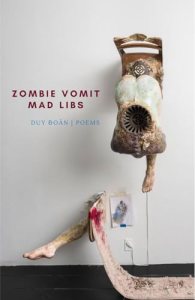

Zombie Vomit Mad Libs by Duy Đoàn

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

To be published in the USA by Alice James Books on November 12. With thanks to the publisher for the advanced e-copy for review.

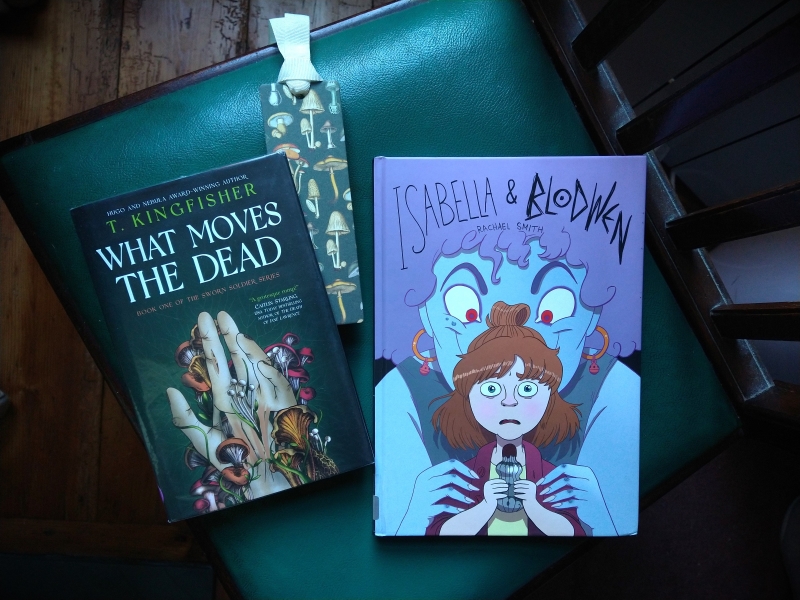

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher (2022)

{MILD SPOILERS AHEAD}

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

At first it seemed the author was awkwardly inserting a nonbinary character into history, but it’s more complicated than that. The sworn soldier tradition in countries such as Albania was a way for women, especially orphans or those who didn’t have brothers to advocate for them, to have autonomy in martial, patriarchal cultures. Kingfisher makes up European nations and their languages, as well as special sets of pronouns to refer to soldiers (ka/kan), children (va/van), etc. She doesn’t belabour the world-building, just sketches in the bits needed.

This was a quick and reasonably engaging read, though I wasn’t always amused by Kingfisher’s gleefully anachronistic tone (“Mozart? Beethoven? Why are you asking me? It was music, it went dun-dun-dun-DUN, what more do you want me to say?”). I wondered if the plot might have been inspired by a detail in Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, but it seems more likely it’s a half-conscious addition to a body of malevolent-mushroom stories (Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, various by Jeff VanderMeer, The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley). I was drawn in by Easton’s voice and backstory enough to borrow the sequel, about which more anon. (T. Kingfisher is the pen name of Ursula Vernon.) (Public library)

Isabella & Blodwen by Rachael Smith (2023)

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

It’s a sweet enough story, but a few issues detracted from my enjoyment. Issy is often depicted more like a ten-year-old. I don’t love the blocky and exaggerated features Smith gives her characters, or the Technicolor hues. And I found myself rolling my eyes at how the book unnaturally inserts a sexual harassment theme – which Blodwen responds to in modern English, having spoken in archaic fashion up to that point, and with full understanding of the issue of consent. I can imagine younger teens enjoying this, though. (Public library)

The mini playlist I had going through my mind as I wrote this:

- “Running with Zombies” by The Bookshop Band (inspired by The Making of Zombie Wars by Aleksandar Hemon)

- “Flesh and Blood Dance” by Duke Special

- “Dead Alive” by The Shins

And to counterbalance the evil fungi of the Kingfisher novella, here’s Anne-Marie Sanderson employing the line “A mycelium network is listening to you” in a totally non-threatening way. It’s one of the multiple expressions of reassurance in her lovely song “All Your Atoms,” my current earworm from her terrific new album Old Light.

Summer Reading, Part II: Beanland, Watters; O’Farrell, Oseman Rereads

Apparently the UK summer officially extends to the 22nd – though you’d never believe it from the autumnal cold snap we’re having just now – so that’s my excuse for not posting about the rest of my summery reading until today. I have a tender ancestry-inspired story of a Jewish family’s response to grief, a bizarre YA fantasy comic, and two rereads, one a family story from one of my favourite contemporary authors and the other the middle instalment in a super-cute graphic novel series.

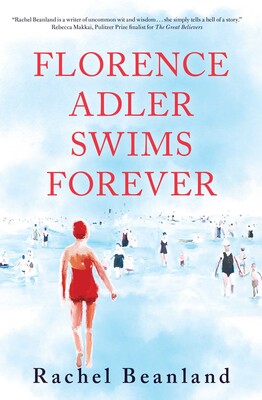

Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland (2020)

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

After reviewing Beanland’s second novel, The House Is on Fire, I wanted to catch up on her debut. Both are historical and give a broad but detailed view of a particular milieu and tragic event through the use of multiple POVs. It’s the summer of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Florence, a plucky college student who intends to swim the English Channel, drowns on one of her practice swims. This happens in the first chapter (and is announced in the blurb), so the rest is aftermath. The Adlers make the unusual decision to keep Florence’s death from her sister, Fannie, who is on hospital bedrest during her third pregnancy because she lost a premature baby last year. Fannie’s seven-year-old daughter, Gussie, is sworn to silence about her aunt – with Stuart, the lifeguard who loved Florence, and Anna, a German refugee the Adlers have sponsored, turning it into a game for her by creating the top-secret “Florence Adler Swims Forever Society” with its own language.

The particulars can be chalked up to family history: this really happened; the Gussie character was Beanland’s grandmother, and the author believes her great-great-aunt Florence died of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It’s intriguing to get glimpses of Jewish ritual, U.S. anti-Semitism and early concern over Nazism, but I was less engaged with other subplots such as Fannie’s husband Isaac’s land speculation in Florida. There’s a satisfying queer soupcon, and Beanland capably inhabits all of the perspectives and the bereaved mindset. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Lumberjanes: Campfire Songs by Shannon Watters et al. (2020)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library)

This comics series created by a Boom! Studios editor ran from 2014 to 2020 and stretched to 75 issues that have been collected in 20+ volumes. Watters wanted to create a girl-centric comic and roped in various writers who together decided on the summer scout camp setting. I didn’t really know what I was getting into with this set of six stand-alone stories, each illustrated by a different artist. The characters are recognizably the same across the stories, but the variation in style meant I didn’t know what they’re “supposed” to look like. All are female or nonbinary, including queer and trans characters. I guess I expected queer coming-of-age stuff, but this is more about friendship and fantastical adventures. Other worlds are just a few steps away. They watch the Northern Lights with a pair of yeti, attend a dinner party cooked by a ghost chef, and play with green kittens and giant animate pumpkins. My favourite individual story was “A Midsummer Night’s Scheme,” in which Puck the fairy interferes with preparations for a masquerade ball. I won’t bother reading other installments. (Public library) ![]()

And the rereads:

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell (2013)

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I read this when it first came out (original review here) and saw O’Farrell speak on it, in conversation with Julie Cohen, at a West Berkshire Libraries event – several years before I lived in the county. I expected it to be a little more atmospheric about the infamous UK drought of summer 1976. All I’d remembered otherwise was that one character is hiding illiteracy and another has an affair while leading a residential field trip. The novel opens, Harold Fry-like, with Robert Riordan disappearing from his suburban home. Gretta phones each of her adult children to express concern, but she’s so focussed on details like how she’ll get into the shed without Robert’s key that she fails to convey the gravity of the situation. Eventually the three descend on her from London, Gloucestershire and New York and travel to Ireland together to find him, but much of the novel is a patient filling-in of backstory: why Monica and Aoife are estranged, what went wrong in Michael Francis’s marriage, and so on.

I had forgotten the two major reveals, but this time they didn’t seem as important as the overall sense of decisions with unforeseen consequences. O’Farrell was using extreme weather as a metaphor for risk and cause-and-effect (“a heatwave will act upon people. It lays them bare, it wears down their guard. They start behaving not unusually but unguardedly”), and it mostly works. But this wasn’t a top-tier O’Farrell on a reread. (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Average: ![]()

Heartstopper: Volume 3 by Alice Oseman (2020)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library)

Heartstopper was my summer crush back in 2021, and I couldn’t resist rereading the series in the hardback reissue. That I started with the middle volume (original review here) is an accident of when my library holds arrived for me, but it turned out to be an apt read for the Olympics summer because it mostly takes place during a one-week school trip to Paris, full of tourism, ice cream, hijinks and romance. Nick and Charlie are dating but still not out to everyone in their circle. This is particularly true for Nick, who is a jock and passes as straight but is actually bisexual. Charlie experienced a lot of bullying at his boys’ school before his coming-out, so he’s nervous for Nick, and the psychological effects persist in his disordered eating. Oseman deals sensitively with mental health issues here, and has fun adding more queer stories into the background: Darcy and Tara, Tao and Elle (trans), and even the two male trip chaperones. It’s adorable how everything flirtation-related is so dramatic and the characters are always blushing and second-guessing. Lucky teens who get to read this at the right time. (Public library) ![]()

Any final “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in  Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters.

Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters. This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle.

This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle. This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.” Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s  Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 (

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 ( I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels (

I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels ( The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after

The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after  This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which

This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which  There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for

There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for  The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)  Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)

Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)  The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in

The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in  McCracken is terrific in short forms:

McCracken is terrific in short forms:  Compared to

Compared to  These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).

These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).  I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the

I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the  This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to  Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis.

Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis. I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to