Weatherglass Novella Prize 2026

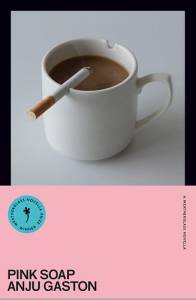

Following up on the shortlist news I shared in November: Ali Smith has chosen two winners for the second annual Weatherglass Novella Prize. Both of these have changed title since they were submitted as manuscripts (From the Smallest Things to The Hyena’s Daughter; Shougani to Pink Soap). I’m particularly interested in Jones’s novel about Mary Shelley and her sister and stepsister. And the Gaston has a brilliant cover!

Here’s what Ali Smith had to say about the winning books, courtesy of the Weatherglass Substack:

The Hyena’s Daughter by Jupiter Jones

(to be published in April 2026)

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – ‘how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?’ – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This novella, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.”

Pink Soap by Anju Gaston

(to be published in June 2026)

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“Pink Soap examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.”

Submissions have already opened for the 2027 Prize. More information is here.

#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

#NovNov25 Catch-Up: Dodge, Garner, O’Collins, Sagan and A. White

As promised, I’m catching up on five novella-length works I finished in November. In fiction, I have an odd duck of a family story, a piece of autofiction about caring for a friend with cancer, a record of an affair, and a tale of settling two new cats into home life in the 1950s. And in nonfiction, a short book about the religious approach to midlife crisis.

Fup by Jim Dodge (1983)

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages]

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages] ![]()

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (2008)

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages]

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages] ![]()

Second Journey: Spiritual Awareness and the Mid-Life Crisis by Gerald O’Collins SJ (1978; 1995)

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages]

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages] ![]()

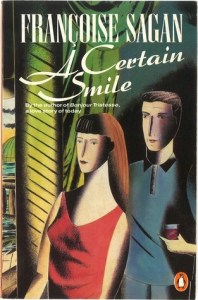

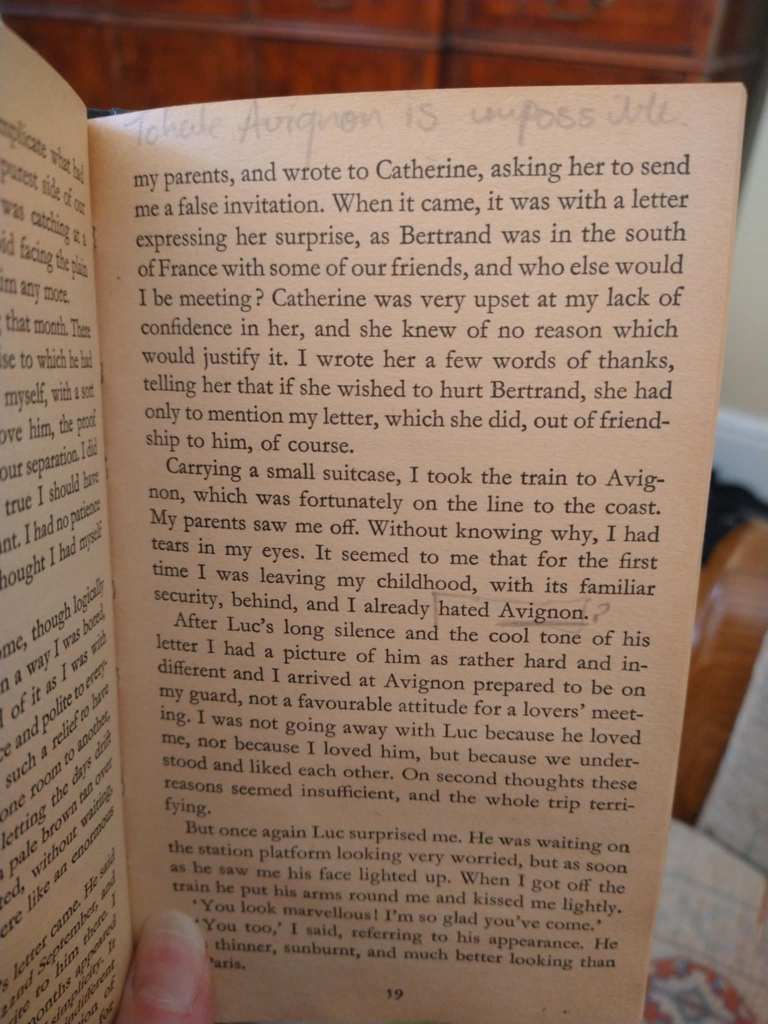

A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan (1956)

[Translated from French by Irene Ash]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages] ![]()

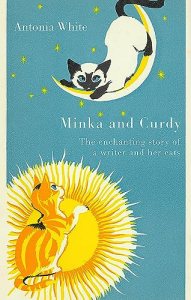

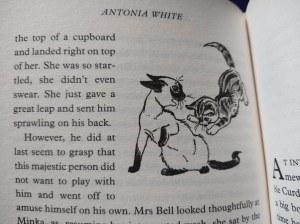

Minka and Curdy by Antonia White; illus. Janet and Anne Johnstone (1957)

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages]

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages] ![]()

I also had a few DNFs last month:

- The Book of Colour by Julia Blackburn (1995) seemed a good bet because I’ve enjoyed some of Blackburn’s nonfiction and it was on the Orange Prize shortlist. But after 60 pages I still had no idea what was going on amid the Mauritius-set welter of family history and magic realism. (Secondhand – Bas Books charity shop, 2022)

- A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood (1964) lured me because I’d so loved Goodbye to Berlin and I remember liking the Colin Firth film. But this story of an Englishman secretly mourning his dead partner while trying to carry on as normal as a professor in Los Angeles was so dreary I couldn’t persist. (Public library)

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel (2025) – JLS could write one of these mini nature volumes in his sleep. (Maybe he did with this one, actually?) I’d rather one full-length book from him every few years than bitty, redundant ones annually. (Public library)

- Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse (1974) – I’ve read one Jeeves & Wooster book before and enjoyed it well enough. This felt inconsequential, so as I already had way too many novellas on the go I sent it back whence it came. (Little Free Library)

Final statistics for #NovNov25 coming up tomorrow!

Novellas New to My TBR in #NovNov25

Somehow the rest of November flew away and all my best-laid plans for reviewing my preposterous stack of novellas fell by the wayside. As usual, I enthusiastically started a dozen when I should have just focused on three or four; it is ever thus. We spent the weekend visiting friends and it was also C’s birthday yesterday, so there wasn’t much time for reading. However, I managed to finish another five novellas by the 30th to review later in the week.

I will keep the link-up open through Saturday the 6th for belated reviews and catch-up posts and on Sunday the 7th I will post final statistics for the year’s challenge.

Here are the novellas I’ve added to my TBR this month:

Before the Leaves Fall by Clare O’Dea, reviewed by both Cathy and Susan – Set in Switzerland, it has an assisted dying theme, which always attracts me. It’s also published by the indie Fairlight Books.

Before the Leaves Fall by Clare O’Dea, reviewed by both Cathy and Susan – Set in Switzerland, it has an assisted dying theme, which always attracts me. It’s also published by the indie Fairlight Books.

This one is nonfiction:

Middlemarch and the Imperfect Life by Pamela Erens (from the Bookmarked series), spotted by chance on Liz’s wish list. I do love a memoir that responds to another work of literature.

Middlemarch and the Imperfect Life by Pamela Erens (from the Bookmarked series), spotted by chance on Liz’s wish list. I do love a memoir that responds to another work of literature.

And these two are 2026 releases that are on my radar as review books…

Who Killed Bambi? by Monika Fagerholm (for Foreword Reviews) is about the aftermath of a teen gang rape in Helsinki.

Who Killed Bambi? by Monika Fagerholm (for Foreword Reviews) is about the aftermath of a teen gang rape in Helsinki.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico (for Shelf Awareness) is a response to her spouse transitioning.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico (for Shelf Awareness) is a response to her spouse transitioning.

Whew, four isn’t so overwhelming!

Four for #NonfictionNovember and #NovNov25: Hanff, Humphrey, Kimmerer & Steinbeck

I’ll be doubling up posts most days for the rest of this month to cram everything in!

Today I have a cosy companion story to a beloved bibliophiles’ classic, a comprehensive account of my favourite beverage, a refreshing Indigenous approach to economics, and a journalistic exposé that feels nearly as relevant now as it did 90 years ago.

Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff (1985)

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages]

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages] ![]()

Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey (2020)

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages]

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages] ![]()

The Serviceberry: An Economy of Gifts and Abundance by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2024)

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages]

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages] ![]()

The Harvest Gypsies: On the Road to The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (1936; 1988)

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages]

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages] ![]()

Check out Kris Drever’s folk song “Harvest Gypsies” (written by Boo Hewerdine) here.

Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

Weatherglass Books’ Second Annual Novella Prize Shortlist (#NovNov25)

Last year I attended an event at Foyles in London introducing the two joint winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. I later reviewed both Astraea by Kate Kruimink and Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, and interviewed Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths. With his permission, I’m reproducing below the partial text of the Substack post in which he announced the shortlist for this second year of the award. Out of 170+ submissions, he and co-publisher Damian Lanigan chose a shortlist of four novellas, which have again been sent to Ali Smith for her to choose a winner in the new year. The winner will be published by Weatherglass Books. It’s clear that all four are publishable, though!

The shortlist is … in no particular order:

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR by Selma Carvalho is a piece of sensuous magnetic power and aliveness. It deals with questions of class, ethnicity and nationalism so close to the contemporary that this book almost shakes in your hands.

Two people sit by chance near each other on a bus in a world where the rise of political divisions is physical, palpable. They’re unalike in every way. Their attraction fizzes like a lit fuse. “What does it mean to be foreign, to think of another human being as foreign? Foreign from what?” It examines the closeness and distance between people, families, tribes, and the hair-trigger, hair-on-the-back-of-the-neck negotiations between people’s bodies.

Wise and contemporary, uncompromising and true, its edginess, and the fallout from desires, personal and social, is brilliantly conjured and conveyed.

FROM THE SMALLEST THINGS by Jupiter Jones tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step-sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of “a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.”

It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – “how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?” – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This book, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.

Ali Smith at the Weatherglass event in September 2024.

SHOUGANI by Anju Gaston – what does it mean? “I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.” This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgiveable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

Shougani examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.

THE MARVELLOUS DINNER by Polly Tuckett

“A massacre of things just to produce a single dish”: this novella charts the terrible coming-apart of a marriage. A wife prepares a dinner for her husband on an important anniversary, a meal so laboured and elaborate that something’s wrong, something’s definitely up – more, something’s got to give.

This novella is a story of the fictions we call true in our lives, even though we know they’re hollow ceremonials. There’s a Mike Leigh touch to this unsettling book. Every mouthful is dangerous, precarious. It anatomises fuss and ceremony, examines the ritual and the real bullying in a relationship. It deals with madness and the mundane truth of fantasy. Is it love itself that’s a delusion in this tale of the ties that bind?

“So there we have it. Our four shortlisted titles,” Neil writes. “They are all extraordinary, all deserve to win, to be well published. It’s now down to Ali. Thank you to everyone who submitted. We’ve enjoyed reading all the entries. But especial thanks to Ali Smith for agreeing to be our judge in year one and now on-goingly; it’s a real privilege to have one the world’s most original writers helping us select what we commission.”

Which of the synopses entice you? I especially like the sound of From the Smallest Things and The Marvellous Dinner.

#NovNov25 Begins! & My Year in Novellas

Welcome to Novellas in November! The link-up is open (see my pinned post). At the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about any novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a designated shelf of short books that I keep adding to throughout the year. Whenever I’m at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, the Little Free Library, or the public library volunteering, I’m always eyeing up thin volumes and thinking about my piles for November.

But I read novellas other times of year, too. Forty-five of them between December 2024 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year the figure was 44 and the year before it was 46, so that’s my natural average). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness, so that helps to account for the number. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My four favourites are ones I’ve already covered on the blog (links to my reviews): The Most by Jessica Anthony, Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler; and, in nonfiction, Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba. Two works of historical fiction, one contemporary story; and a memoir of life with a cat.

What are some of your recent favourite novellas?

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]