20 Books of Summer, 17–20: Bennett, Davidson, Diffenbaugh, Kimmerer

As per usual, I’m squeezing in my final 20 Books of Summer reviews late on the very last day of the challenge. I’ll call it a throwback to the all-star procrastination of my high school and college years. This was a strong quartet to finish on: two novels, the one about (felling) trees and the other about communicating via flowers; and two nonfiction books about identifying trees and finding harmony with nature.

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees by Ros Bennett; illus. Nell Bennett (2022)

Botanist Ros Bennett has designed this as a user-friendly guide that can be taken into the field to identify 52 of Britain’s most common trees. Most of these are native species, plus a few naturalized ones. “Walks in the countryside … take on a new dimension when you find yourself on familiar, first-name terms with the trees around you,” she encourages. She introduces tree families, basics of plant anatomy and chemistry, and the history of the country’s forests before moving into identification. Summer leaves make ID relatively easy with a three-step set of keys, explained in words as well as with impressively detailed black-and-white illustrations of representative species’ leaves (by her daughter, Nell Bennett).

Seasonality makes things trickier: “Identifying plants is not rocket science, though occasionally it does require lots of patience and a good hand lens. Identifying trees in winter is one of those occasions.” This involves a close look at details of the twigs and buds – a challenge I’ll be excited to take up on canalside walks later this year. The third section of the book gives individual profiles of each featured species, with additional drawings. I learned things I never realized I didn’t know (like how to pronounce family names, e.g., Rosaceae is “Rose-A-C”), and formalized other knowledge. For instance, I can recognize an ash tree by sight, but now I know you identify an ash by its 9–13 compound, opposite, serrated leaflets.

Some of the information was more academic than I needed (as with one of my earlier summer reads, The Ash Tree by Oliver Rackham), but it’s easy to skip any sections that don’t feel vital and come back to them another time. I most valued the approachable keys and their accompanying text, and will enjoy taking this compact naked hardback on autumn excursions. Bennett never dumbs anything down, and invites readers to delight in discovery. “So – go out, introduce yourself to your neighbouring trees and wonder at their beauty, ingenuity and variety.”

With thanks to publicist Claire Morrison and Welbeck for the free copy for review.

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (2021)

When this would-be Great American Novel* arrived unsolicited through my letterbox last summer, I was surprised I’d not encountered the pre-publication buzz. The cover blurb is from Nickolas Butler, which gives you a pretty good sense of what you’re getting into: a gritty, working-class story set in what threatens to be an overwhelmingly male milieu. For generations, Rich Gundersen’s family has been involved in logging California’s redwoods. Davidson is from Arcata, California, and clearly did a lot of research to recreate an insider perspective and a late 1970s setting. There is some specialist vocabulary and slang (the loggers call the largest trees “big pumpkins”), but it’s easy enough to understand in context.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

A major element, then, is people gradually waking up to the damage chemicals are doing to their waterways and, thereby, their bodies. The problem, for me, was that I realized this much earlier than any of the characters, and it felt like Davidson laid it on too thick with the many examples of human and animal deaths and deformities. This made the book feel longer and less subtle than, e.g., The Overstory. I started it as a buddy read with Marcie (Buried in Print) 11 months ago and quickly bailed, trying several more times to get back into the book before finally resorting to skimming to the end. Still, especially for a debut author, Davidson’s writing chops are impressive; I’ll look out for what she does next.

*I just spotted that it’s been shortlisted for the $25,000 Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the proof copy for review.

The Language of Flowers by Vanessa Diffenbaugh (2011)

The cycle would continue. Promises and failures, mothers and daughters, indefinitely.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

In Diffenbaugh’s debut, Victoria Jones ages out of foster care at 18 and leaves her group home for an uncertain future. She spends time homeless in San Francisco but her love of flowers, and particularly the Victorian meanings assigned to them, lands her work in a florist’s shop and reconnects her with figures from her past. Chapters alternate between her present day and the time she came closest to being adopted – by Elizabeth, who owned a vineyard and loved flowers, when she was nine. We see how estrangements and worries over adequate mothering recur, with Victoria almost a proto-‘Disaster Woman’ who keeps sabotaging herself. Throughout, flowers broker reconciliations.

I won’t say more about a plot that would be easy to spoil, but this was a delight and reminded me of a mini flower dictionary with a lilac cover and elaborate cursive script that I owned when I was a child. I loved the thought that flowers might have secret messages, as they do for the characters here. Whatever happened to that book?! (Charity shop)

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013)

I’d heard Kimmerer recommended by just about every nature writer around, North American or British, and knew I needed this on my shelf. Before I ever managed to read it, I saw her interviewed over Zoom by Lucy Jones in July 2021 about her other popular science book, Gathering Moss, which was first published 18 years ago but only made it to the UK last year. So I knew what a kind and peaceful person she is: she just emanates warmth and wisdom, even over a computer screen.

And I did love Braiding Sweetgrass nearly as much as I expected to, with the caveat that the tiny-print 400 pages of my paperback edition make the essays feel very dense. I could only read a handful of pages in a sitting. Also, after about halfway, it started to feel a bit much, like maybe she had given enough examples from her life, Native American legend and botany. The same points about gratitude for the gifts of the Earth, kinship with other creatures, responsibility and reciprocity are made over and over.

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

I most enjoyed the shorter essays that draw on her fieldwork or her experience of motherhood. “The Gift of Strawberries” – “An Offering” – “Asters and Goldenrod” make a stellar three-in-a-row, and “Collateral Damage” is an excellent later one about rescuing salamanders from the road, i.e. doing the small thing that we can do rather than being overwhelmed by the big picture of nature in crisis. “The Sound of Silverbells” is one of the most well-crafted individual pieces, about taking a group of students camping when she lived in the South. At first their religiosity (creationism and so on) grated, but when she heard them sing “Amazing Grace” she knew that they sensed the holiness of the Great Smoky Mountains.

But the pair I’d recommend most highly, the essays that made me weep, are “A Mother’s Work,” about her time restoring an algae-choked pond at her home in upstate New York, and its follow-up, “The Consolation of Water Lilies,” about finding herself with an empty nest. Her loving attention to the time-consuming task of bringing the pond back to life is in parallel to the challenges of single parenting, with a vision of the passing of time being something good rather than something to resist.

Here are just a few of the many profound lines:

For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.

I’m a plant scientist and I want to be clear, but I am also a poet and the world speaks to me in metaphor.

Ponds grow old, and though I will too, I like the ecological idea of aging as progressive enrichment, rather than progressive loss.

This will be a book to return to time and again. (Gift from my wish list several years ago)

I also had one DNF from this summer’s list:

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson: This reminded me of a cross between The Crow Road by Iain Banks and The Heavens by Sandra Newman, what with the teenage narrator and a vague time travel plot with some Shakespearean references. I put it on the pile for this challenge because I’d read it had a forest setting. I haven’t had much luck with Atkinson in the past and this didn’t keep me reading past page 60. (Little Free Library)

A Look Back at My 20 Books of Summer 2022

Half of my reads are pictured here. The rest were e-books (represented by the Kindle) or have already had to go back to the library.

My fiction standout was The Language of Flowers, reviewed above. Nonfiction highlights included Forget Me Not and Braiding Sweetgrass, with Tree-Spotting the single most useful book overall. I also enjoyed reading a couple of my selections on location in the Outer Hebrides. The hands-down loser (my only 1-star rating of the year so far, I think?) was Bonsai. As always, there are many books I could have included and wished I’d found the time for, like (on my Kindle) A House among the Trees by Julia Glass, This Is Your Mind on Plants by Michael Pollan and Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard.

At the start, I was really excited about my flora theme and had lots of tempting options lined up, some of them literally about trees/flowers and others more tangentially related. As the summer went on, though, I wasn’t seeing enough progress so scrambled to substitute in other things I was reading from the library or for paid reviews. This isn’t a problem, per se, but my aim with this challenge has generally been to clear TBR reads from my own shelves. Maybe I didn’t come up with enough short and light options (just two novella-length works and a poetry collection; only the Diffenbaugh was what I’d call a page-turner); also, even with the variety I’d built in, having a few plant quest memoirs got a bit samey.

Next year…

I’m going to skip having a theme and set myself just one simple rule: any 20 print books from my shelves (NOT review copies). There will then be plenty of freedom to choose and substitute as I go along.

Three on a Theme: Novels of Female Friendship

Friendship is a fairly common theme in my reading and, like sisterhood, it’s an element I can rarely resist. When I picked up a secondhand copy of Female Friends (below) in a charity shop in Hexham over the summer, I spied a chance for another thematic roundup. I limited myself to novels I’d read recently and to groups of women friends.

Before Everything by Victoria Redel (2017)

I found out about this one from Susan’s review at A life in books (and she included it in her own thematic roundup of novels on friendship). “The Old Friends” have known each other for decades, since elementary school. Anna, Caroline, Helen, Ming and Molly. Their lives have gone in different directions – painter, psychiatrist, singer in a rock band and so on – but in March 2013 they’re huddling together because Anna is terminally ill. Over the years she’s had four remissions, but it’s clear the lymphoma won’t go away this time. Some of Anna’s friends and family want her to keep fighting, but the core group of pals is going to have to learn to let her die on her own terms. Before that, though, they aim for one more adventure.

I found out about this one from Susan’s review at A life in books (and she included it in her own thematic roundup of novels on friendship). “The Old Friends” have known each other for decades, since elementary school. Anna, Caroline, Helen, Ming and Molly. Their lives have gone in different directions – painter, psychiatrist, singer in a rock band and so on – but in March 2013 they’re huddling together because Anna is terminally ill. Over the years she’s had four remissions, but it’s clear the lymphoma won’t go away this time. Some of Anna’s friends and family want her to keep fighting, but the core group of pals is going to have to learn to let her die on her own terms. Before that, though, they aim for one more adventure.

Through the short, titled sections, some of them pages in length but others only a sentence or two, you piece together the friends’ history and separate struggles. Here’s an example of one such fragment, striking for the frankness and intimacy; how coyly those bald numbers conceal such joyful and wrenching moments:

Actually, for What It’s Worth

Between them there were twelve delivered babies. Three six- to eight-week abortions. Three miscarriages. One post-amniocentesis selective abortion. That’s just for the record.

While I didn’t like this quite as much as Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, which is similar in setup, it’s a must-read on the theme. It’s sweet and sombre by turns, and has bite. I also appreciated how Redel contrasts the love between old friends with marital love and the companionship of new neighbourly friends. I hadn’t heard of Redel before, but she’s published another four novels and three poetry collections. It’d be worth finding more by her. The cover image is inspired by a moment late in a book when they find a photograph of the five of them doing handstands in a sprinkler the summer before seventh grade. (Public library)

Female Friends by Fay Weldon (1974)

Like a cross between The Orchard on Fire by Shena Mackay and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer; this is the darkly funny story of Marjorie, Chloe and Grace: three Londoners who have stayed friends ever since their turbulent childhood during the Second World War, when Marjorie was sent to live with Grace and her mother. They have a nebulous brood of children between them, some fathered by a shared lover (a slovenly painter named Patrick). Chloe’s husband is trying to make her jealous with his sexual attentions to their French nanny. Marjorie, who works for the BBC, is the only one without children; she has a gynaecological condition and is engaged in a desultory search for her father.

Like a cross between The Orchard on Fire by Shena Mackay and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer; this is the darkly funny story of Marjorie, Chloe and Grace: three Londoners who have stayed friends ever since their turbulent childhood during the Second World War, when Marjorie was sent to live with Grace and her mother. They have a nebulous brood of children between them, some fathered by a shared lover (a slovenly painter named Patrick). Chloe’s husband is trying to make her jealous with his sexual attentions to their French nanny. Marjorie, who works for the BBC, is the only one without children; she has a gynaecological condition and is engaged in a desultory search for her father.

The book is mostly in the third person, but some chapters are voiced by Chloe and occasional dialogues are set out like a film script. I enjoyed the glimpses I got into women’s lives in the mid-20th century via the three protagonists and their mothers. All are more beholden to men than they’d like to be. But there’s an overall grimness to this short novel that left me wincing. I’d expected more nostalgia (“they are nostalgic, all the same, for those days of innocence and growth and noise. The post-war world is drab and grey and middle-aged. No excitement, only shortages and work”) and warmth, but this friendship trio is characterized by jealousy and resentment. (Secondhand copy)

The Weekend by Charlotte Wood (2019)

“It was exhausting, being friends. Had they ever been able to tell each other the truth?”

It’s the day before Christmas Eve as seventysomethings Jude, Wendy and Adele gather to clear out their late friend’s Sylvie’s house in a fictional coastal town in New South Wales. This being Australia, that means blazing hot weather and a beach barbecue rather than a cosy winter scene. Jude is a bristly former restaurateur who has been the mistress of a married man for many years. Wendy is a widowed academic who brings her decrepit dog, Finn, along with her. Adele is a washed-up actress who carefully maintains her appearance but still can’t find meaningful work.

It’s the day before Christmas Eve as seventysomethings Jude, Wendy and Adele gather to clear out their late friend’s Sylvie’s house in a fictional coastal town in New South Wales. This being Australia, that means blazing hot weather and a beach barbecue rather than a cosy winter scene. Jude is a bristly former restaurateur who has been the mistress of a married man for many years. Wendy is a widowed academic who brings her decrepit dog, Finn, along with her. Adele is a washed-up actress who carefully maintains her appearance but still can’t find meaningful work.

They know each other so well, faults and all. Things they think they’ve hidden are beyond obvious to the others. And for as much as they miss Sylvie, they are angry at her, too. But there is also a fierce affection in the mix that I didn’t sense in the Weldon: “[Adele] remembered them from long ago, two girls alive with purpose and beauty. Her love for them was inexplicable. It was almost bodily.” Yet Wendy compares their tenuous friendship to the Great Barrier Reef coral, at risk of being bleached.

It’s rare to see so concerted a look at women in later life, as the characters think back and wonder if they’ve made the right choices. There are plenty of secrets and self-esteem struggles, but it’s all encased in an acerbic wit that reminded me of Emma Straub and Elizabeth Strout. Terrific stuff. (Twitter giveaway win)

Some favourite lines:

“The past was striated through you, through your body, leaching into the present and the future.”

“Was this what getting old was made of? Routines and evasions, boring yourself to death with your own rigid judgements?”

On this theme, I have also read: The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames, Catch the Rabbit by Lana Bastašić, The Group by Lara Feigel (and Mary McCarthy), My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, Expectation by Anna Hope, Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney, and The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker.

If you read just one … The Weekend was the best of this bunch for me.

Have you read much on this topic?

Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

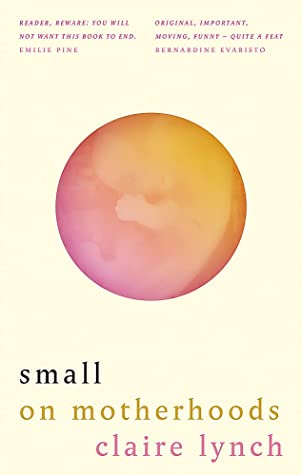

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch

A line from Berney’s memoir makes a good transition into this one: “I felt a sense of dread: if I turned out to be gay I believed my life would become unbearably small.” The word “small” is a sort of totem here, a reminder of the microscopic processes and everyday miracles that go into making babies, as well as of the vulnerability of newborns – and of hope.

Lynch and her partner Beth’s experience in England was reminiscent of Berney’s in many ways, but with a key difference: through IVF, Lynch’s eggs were added to donor sperm to make the embryos implanted in Beth’s uterus. Mummy would have the genetic link, Mama the physical tie of carrying and birthing. It took more than three years of infertility treatment before they conceived their twin girls, born premature; they were followed by another daughter, creating a crazy but delightful female quintet. The account of the time when their daughters were in incubators reminded me of Francesca Segal’s Mother Ship.

There are two intriguing structural choices that make small stand out. The first you’d notice from opening the book at random, or to page 1. It is written in a hybrid form, the phrases and sentences laid out more like poetry. Although there are some traditional expository paragraphs, more often the words are in stanzas or indented. Here’s an example of what this looks like on the page. It also happens to be from one of the most ironically funny parts of the book, when Lynch is grouped in with the dads at an antenatal class:

It’s a fast-flowing, artful style that may remind readers of Bernardine Evaristo’s work (and indeed, Evaristo gives one of the puffs). The second interesting decision was to make the book turn on a revelation: at the exact halfway mark we learn that, initially, the couple intended to have opposite roles: Lynch tried to get pregnant with Beth’s baby, but miscarried. Making this the pivot point of the memoir emphasizes the struggle and grief of this experience, even though we know that it had a happy ending.

With thanks to Brazen Books for the free copy for review.

How We Do Family by Trystan Reese

We mostly have Trystan Reese to thank for the existence of a pregnant man emoji. A community organizer who works on anti-racist and LGBTQ justice campaigns, Reese is a trans man married to a man named Biff. They expanded their family in two unexpected ways: first by adopting Biff’s niece and nephew when his sister’s situation of poverty and drug abuse meant she couldn’t take care of them, and then by getting pregnant in the natural (is that even the appropriate word?) way.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

I realized when reading this and Detransition, Baby that my view of trans people is mostly post-op because of the only trans person I know personally, but a lot of people choose never to get surgical confirmation of gender (or maybe surgery is more common among trans women?). We’ve got to get past the obsession with genitals. As Reese writes, “we are just loving humans, like every human throughout all of time, who have brought a new life into this world. Nothing more than that, and nothing less. Just humans.”

This is a very fluid, quick read that recreates scenes and conversations with aplomb, and there are self-help sections after most chapters about how to be flexible and have productive dialogue within a family and with strangers. If literary prose and academic-level engagement with the issues are what you’re after, you’d want to head to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts instead, but I also appreciated Reese’s unpretentious firsthand view.

And here’s further evidence of my own bias: the whole time I was reading, I felt sure that Reese must be the figure on the right with reddish hair, since that looked like a person who could once have been a woman. But when I finished reading I looked up photos; there are many online of Reese during pregnancy. And NOPE, he is the bearded, black-haired one! That’ll teach me to make assumptions. (Published by The Experiment. Read via NetGalley)

Plus a bonus essay from the Music.Football.Fatherhood anthology, DAD:

“A Journey to Gay Fatherhood: Surrogacy – The Unimaginable, Manageable” by Michael Johnson-Ellis

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

(I have a high school acquaintance who has gone down this route with his husband – they’re about to meet their daughter and already have a two-year-old son – so I was curious to know more about it, even though their process in the USA might be subtly different.)

On the subject of queer family-making, I have also read: The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson ( ) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (

) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg ( ).

).

If you read just one … Claire Lynch’s small was the one I enjoyed most as a literary product, but if you want to learn more about the options and process you might opt for Jennifer Berney’s The Other Mothers; if you’re particularly keen to explore trans issues and LGTBQ activism, head to Trystan Reese’s How We Do Family.

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

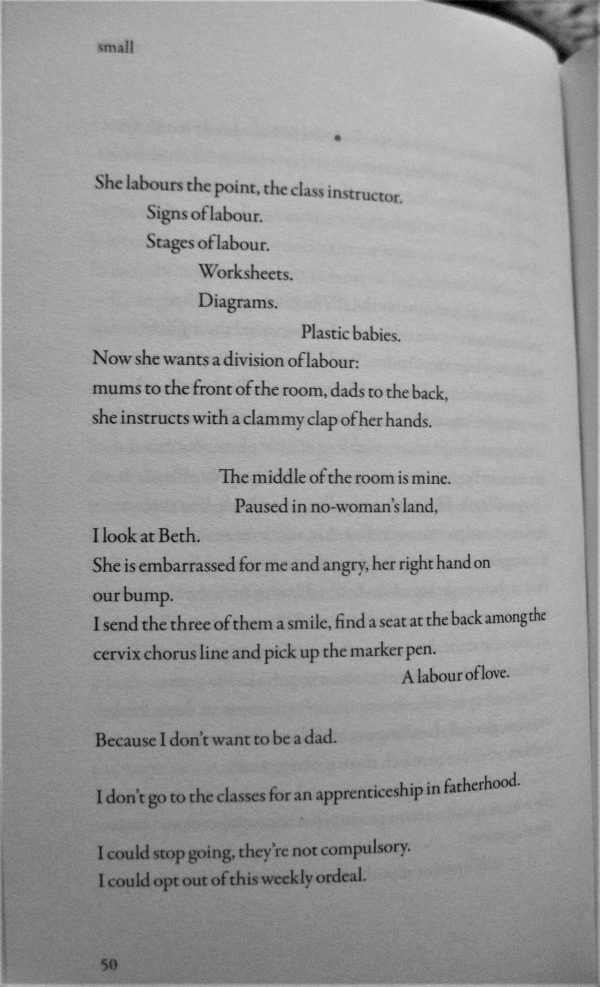

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.” The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head. Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in  There’s a character named Verena in What Concerns Us by Laura Vogt and Summer by Edith Wharton. Add on another called Verona from Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana.

There’s a character named Verena in What Concerns Us by Laura Vogt and Summer by Edith Wharton. Add on another called Verona from Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana.

In Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell, Polly Pullar is mentioned as one of the writers at that year’s Wigtown Book Festival; I was reading her The Horizontal Oak at the same time.

In Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell, Polly Pullar is mentioned as one of the writers at that year’s Wigtown Book Festival; I was reading her The Horizontal Oak at the same time.

It was

It was  I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close.

I’ve read a couple of Ferris’s novels but this collection had passed me by. “More Abandon (Or Whatever Happened to Joe Pope?)” is set in the same office building as Then We Came to the End. Most of the entries take place in New York City or Chicago, with “Life in the Heart of the Dead” standing out for its Prague setting. The title story, which opens the book, sets the tone: bristly, gloomy, urbane, a little bit absurd. A couple are expecting their friends to arrive for dinner any moment, but the evening wears away and they never turn up. The husband decides to go over there and give them a piece of his mind, only to find that they’re hosting their own party. The betrayal only draws attention to the underlying unrest in the original couple’s marriage. “Why do I have this life?” the wife asks towards the close. These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad.

These 40 flash fiction stories try on a dizzying array of genres and situations. They vary in length from a paragraph (e.g., “Pigeons”) to 5–8 pages, and range from historical to dystopian. A couple of stories are in the second person (“Dandelions” was a standout) and a few in the first-person plural. Some have unusual POV characters. “A Greater Folly Is Hard to Imagine,” whose name comes from a William Morris letter, seems like a riff on “The Yellow Wallpaper,” but with the very wall décor to blame. “Degrees” and “The Thick Green Ribbon” are terrifying/amazing for how quickly things go from fine to apocalyptically bad. Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives.

Having read these 10 stories over the course of a few months, I now struggle to remember what many of them were about. If there’s an overarching theme, it’s (young) women’s relationships. “My First Marina,” about a teenager discovering her sexual power and the potential danger of peer pressure in a friendship, is similar to the title story of Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz. In “Mother’s Day,” a woman hopes that a pregnancy will prompt a reconciliation between her and her estranged mother. In “Childcare,” a girl and her grandmother join forces against the mum/daughter, a would-be actress. “Currency” is in the second person, with the rest fairly equally split between first and third person. “The Doll” is an odd one about a ventriloquist’s dummy and repeats events from three perspectives.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction. In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible).

In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible). In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most.

In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most. Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir

The famous feminist text Our Bodies, Ourselves is mentioned in Birth Notes by Jessica Cornwell and I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins.

The famous feminist text Our Bodies, Ourselves is mentioned in Birth Notes by Jessica Cornwell and I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins.

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also  Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after