The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

Nine Days in Germany and What I Read, Part I: Berlin

We’ve actually been back for more than a week, but soon after our return I was felled by a nasty cold (not Covid, surprisingly), which has left me with a lingering cough and ongoing fatigue. Finally, I’m recovered just about enough to report back.

This Interrail adventure was more low-key than the one we took in 2016. The first day saw us traveling as far as Aachen, just over the border from France. It’s a nice small city with Christian and culinary history: Charlemagne is buried in the cathedral; and it’s famous for a chewy, spicy gingerbread called printen. Before our night in a chain hotel, we stumbled upon the mayor’s Green Party rally in the square – there was to be an election the following day – and drank and dined well. The Gin Library, spotted at random on the map, is an excellent and affordable Asian-fusion cocktail bar. My “Big Ben,” for instance, featured Tanqueray gin, lemon juice, honey, fresh coriander, and cinnamon syrup. Then at Hanswurst – Das Wurstrestaurant (cue jokes about finding the “worst” restaurant in Aachen!), a superior fast-food joint, I had the vegetarian “Hans Berlin,” a scrumptious currywurst with potato wedges.

The next day it was off to Berlin with a big bag of bakery provisions. For the first time, we experienced the rail cancellations and delays that would plague us for much of the next week. We then had to brave the only supermarket open in Berlin on a Sunday – the Rewe in the Hauptbahnhof – before taking the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz, the nearest station to our Airbnb flat.

It was all worth it to befriend Lemmy (the ginger one) and Roxanne. It’s a sweet deal the host has here: whenever she goes away, people pay her to look after her cats. At the same time as we were paying for a cat-sitter back home. We must be chumps!

I’ll narrate the rest of the trip through the books I read. I relished choosing relevant reads from my shelves and the library’s holdings – I was truly spoiled for choice for Berlin settings! – and I appreciated encountering them all on location.

As soon as we walked into the large airy living room of the fifth-floor Airbnb flat, I nearly laughed out loud, for there in the corner was a monstera plant. The trendy, minimalist décor, too, was just like that of the main characters’ place in…

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes]

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss)

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

- Reichstag (Photos 1, 2 and 4 by Chris Foster)

- Reichstag tower designed by Norman Foster

- The Philharmonic

- Brandenburg Gate (Photos 1-3 by Chris Foster)

- Postdam’s Park Sanssouci

- Wen Cheng noodles

- Brammibal’s vegan doughnuts

I brought along another novella that proved an apt companion for our explorations of the city. Even just spotting familiar street and stop names in it felt like reassurance.

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri (2022)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library) ![]()

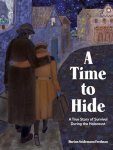

We spent a drizzly and slightly melancholy first day and final morning making pilgrimages to Jewish graveyards and monuments to atrocities, some of them nearly forgotten. I got the sense of a city that has been forced into a painful reckoning with its past – not once but multiple times, perhaps after decades of repression. One morning we visited the claustrophobic monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and, in the Tiergarten, the small memorials to the Roma and homosexual victims of the Holocaust. The Nazis came for political dissidents and the disabled, too, as I was reminded at the Topography of Terrors, a free museum where brutal facts are laid bare. We didn’t find the courage to go in as the timeline outside was confronting enough. I spotted links to the two historical works I was reading during my stay (Stella the red-haired Jew-catcher in the former and Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute in the latter). As I read both, I couldn’t help but think about the current return of fascism worldwide and the gradual erosion of rights that should concern us all.

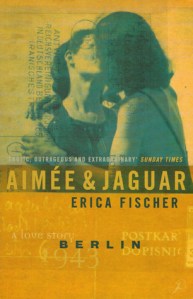

Aimée and Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fischer (1994; 1995)

[Translated from German by Edna McCown]

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Milena and Margarete: A Love Story in Ravensbrück by Gwen Strauss]

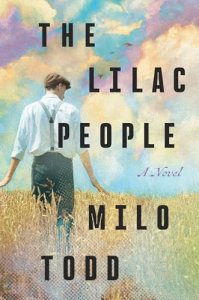

The Lilac People by Milo Todd (2025)

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss)

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Under the Pink Triangle by Katie Moore (set in Dachau)]

We might have been at the Eldorado in the early 1930s on the evening when we ventured out to the bar Zosch for a “New Orleans jazz” evening. The music was superb, the German wine tasty, the whole experience unforgettable … but it sure did feel like being in a bygone era. We’re so used to the indoor smoking ban (in force in the UK since 2007) that we didn’t expect to find young people chain-smoking rollies in an enclosed brick basement, and got back to the flat with our clothes reeking and our lungs burning.

It was good to see visible signs of LGTBQ support in Berlin, though they weren’t as prevalent as I perhaps expected.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

Other Berlin highlights: a delicious vegetarian lunch at the canteen of an architecture firm, the Ritter chocolate shop, and the pigeons nesting on the flat balcony – the chicks hatched on our final morning!

And a belated contribution to Short Story September:

Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue (2006)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Trip write-up to be continued (tomorrow, with any luck)…

20 Books of Summer, 19–20: Emily St. James and Abraham Verghese

Going out on a high! My last three books for the challenge (also including Beautiful Ruins) were particularly great, just the sort of absorbing and rewarding reading that I wish I could guarantee for all of my summer selections.

Woodworking by Emily St. James (2025)

Colloquially, “woodworking” is disappearing in plain sight; doing all you can to fade into the woodwork. Erica has only just admitted her identity to herself, and over the autumn of 2016 begins telling others she’s a woman – starting with her ex-wife Constance, who is now pregnant by her fiancé, John. To everyone else, Erica is still Mr. Skyberg, a 35-year-old English teacher at Mitchell High involved in local amateur dramatics. When Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, Abigail Hawkes, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed new mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. Abigail lives with her adult sister instead, and gains an unexpected surrogate family via her boyfriend Caleb, a Korean adoptee whose mother, Brooke Daniels, is directing Our Town. Brooke is surprisingly supportive given that she attends Isaiah Rose’s megachurch.

As Trump/Pence signs proliferate, a local election is heating up, too: Pastor Rose is running for State Congress on the Republican ticket, opposed by Helen Swee. Erica befriends Helen and becomes faculty advisor for the school’s Democrat club (which has all of two members: Abigail and her Leslie Knope-like friend Megan). The plot swings naturally between the personal and political, emphasizing how the personal business of 1% of the population has been made into a political football. Chapters alternate between Abigail in first person and Erica in third. The characters feel utterly real and the dialogue is as genuine as the narrative voices. The support group Erica and Abigail attend presents a range of trans experiences based on when one came of age. Some are still deep undercover. There’s a big reveal I couldn’t quite accept, though I can see its purpose. It’s particularly effective how St. James lets second- and third-person narration shade into first as characters accept their selves. Grey rectangles cover up deadnames all but once, making the point that even allies can get it wrong.

This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message to convey. It reminded me a lot of Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey but also had the flavour of classic Tom Perrotta (Election). In the Author’s Note, St. James writes, “They say the single greatest determinant of whether someone will support and affirm trans people is if they know a trans person.” I feel lucky to count three trans people among my friends. It’s impossible to make detached pronouncements about bathrooms and slippery slopes if you care about people whose rights and very existence are being undermined. We should all be reading books by and about trans women. (New purchase from Bookshop.org) ![]()

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (2023)

All too often, I shy away from doorstoppers because they seem like too much of a time commitment. Why read 715 pages in one novel when I could read 3.5 of 200 pages each? Yet there’s something special about being lost in the middle of a great big book and trusting that wherever the story goes will be worthwhile. I let this review copy languish on the shelf for over TWO YEARS when I should have known that the author of the amazing Cutting for Stone couldn’t possibly let me down. Verghese’s second novel is very much in the same vein: a family saga that spans decades and in every generation focuses on medical issues. Verghese is a practicing doctor as well as a Stanford professor and you can tell he glories in the details of hand and brain surgeries, disability and rare diseases – and luckily, so do I.

Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but the focus is always on one family in Kerala, starting in 1900 when a 12-year-old girl is brought to the Parambil estate for her arranged marriage to a 40-year-old widower. One day she will be Big Ammachi, the matriarch of a family with a mysterious Condition: In every generation, someone drowns. As a result, they all avoid water, even if it requires going hours out of their way. Her son Philipose longs to be a scholar, but is so hard of hearing that his formal education is cut short. He becomes a columnist in a local newspaper and marries Elsie, a spirited artist. Their daughter, Mariamma, trains as a doctor. In parallel, we follow the story of Digby Kilgour, a Glaswegian surgeon whose career takes him to India. Through Digby and Mariamma’s interactions with colleagues, we watch colonial incompetence and sexism play out. Addiction and suicide recur across the years. Destiny and choice lock horns. I enjoyed the window onto the small community of St. Thomas Christians and felt fond of all the characters, including Damodaran the elephant. It’s also really clever how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between a mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intellectual soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary. ![]()

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the proof copy for review.

I read 10 of the books I selected in my initial planning post. I’m pleased that I picked off a couple of long-neglected review copies and several recent purchases. The rest were substituted at whim. There were two duds, but the overall quality was high, with 10 books I rated 4 stars or higher! Along with the above and Beautiful Ruins, Pet Sematary and Storm Pegs were overall highlights. I also managed to complete a row on the Bingo card, a fun add-on. And, bonus: I cleared 7 books from my shelves by reselling or giving them away after I read them.

Three on a Theme: Trans Poetry for National Poetry Day

Today is National Poetry Day here in the UK. Alfie and I spent part of the chilly early morning reading from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s super Poetry Unbound, an anthology of 50 poems to which he’s devoted personal introductions and exploratory essays. He describes poetry as “like a flame: helping us find our way, keeping us warm.”

Poetry Unbound is also the name of his popular podcast; both were recommended to me by Sara Beth West, my fellow Shelf Awareness reviewer, in this interview we collaborated on back in April (National Poetry Month in the USA) about reading and reviewing poetry. I’ve been a keen reader of contemporary poetry for 15 years or so, but in the 3.5 years that I’ve been writing for Shelf I’ve really ramped up. Most months, I review a couple poetry collections for that site, and another one or more on here.

Two of my Shelf poetry reviews from the past 10 months highlight the trans experience; when I recently happened to read another collection by a trans woman, I decided to gather them together as a trio. All three pair the personal – a wrestling over identity – with the political, voicing protest at mistreatment.

Transitory by Subhaga Crystal Bacon (2023)

In her Isabella Gardner Award-winning fourth collection, queer poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon commemorates the 46 trans and gender-nonconforming people murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020—an “epidemic of violence” that coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The statistics Bacon conveys are heartbreaking: “The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years of age”; “Half of Black trans women spend time in jail”; “Trans people are anywhere/ between eleven and forty percent/ of the homeless population.” She also draws on her own experience of gender nonconformity: “A little butch./ A little femme.” She recalls of visiting drag bars in the 1980s: “We were all/ trying on gender.” And she vows: “No one can say a life is not right./ I have room for you in me.” Her poetic memorial is a valuable exercise in empathy.

Published by BOA Editions. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I was interested to note that the below poets initially published under both female and male, new and dead names, as shown on the book covers. However, a look at social media makes it clear that the trans women are now going exclusively by female names.

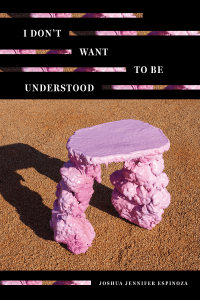

I Don’t Want to Be Understood by Jennifer Espinoza (2024)

In Espinoza’s undaunted fourth poetry collection, transgender identity allows for reinvention but also entails fear of physical and legislative violence.

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Words build into stanzas, prose paragraphs, a zigzag line, or cross-hatching. Espinoza likens the body to a vessel for traumatic memories: “time is a body full of damage// that is constantly trying to forget.” Alliteration and repetition construct litanies of rejection but, ultimately, of hope: “When I call myself a woman I am praying.”

Published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

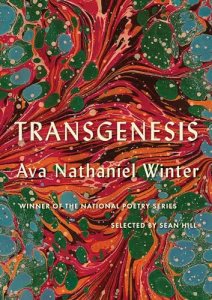

Transgenesis by Ava Winter (2024)

“The body is holy / and is made holy in its changing.”

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Let me greet now,

with warm embrace,

the small blue tablets

I place beneath my tongue each morning.

Oh estradiol,

daily reminder

of what our bodies

have always known:

the many forms of beauty that might be made

flesh by desire, by chance, by animal action.

(from “Transgenesis”)

The first time I wore a dress in public without a hint of irony—a Max Mara wrap adorned with Japanese lilies that framed my shoulders perfectly—I was still thin but also thickly bearded and men on the train whispered to me in a conspiratorial tone, as if they hoped the dress were a joke I might let them in on.

(from “WWII SS Wiking Division Badge, $55”)

– and faith grants affirmation that “there is beauty in such queer and fruitless bodies,” as the title poem insists, with reference to the saris (nonbinary person) acknowledged by the Talmudic rabbis. “Lament with Cello Accompaniment” provides an achingly gorgeous end to the collection:

I do not choose the sound of the song

In my mouth, the fading taste of what I still live through, but I choose this future, as I bury a name defined by grief, as I enter the silence where my voice will take shape.

Winter teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I’ll look out for more of her work.

Published by Milkweed Editions. (Read via Edelweiss)

More trans poetry I have read:

A Kingdom of Love & Eleanor Among the Saints by Rachel Mann

By nonbinary/gender-nonconforming poets, I have also read:

Surge by Jay Bernard

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest

Binded by H Warren

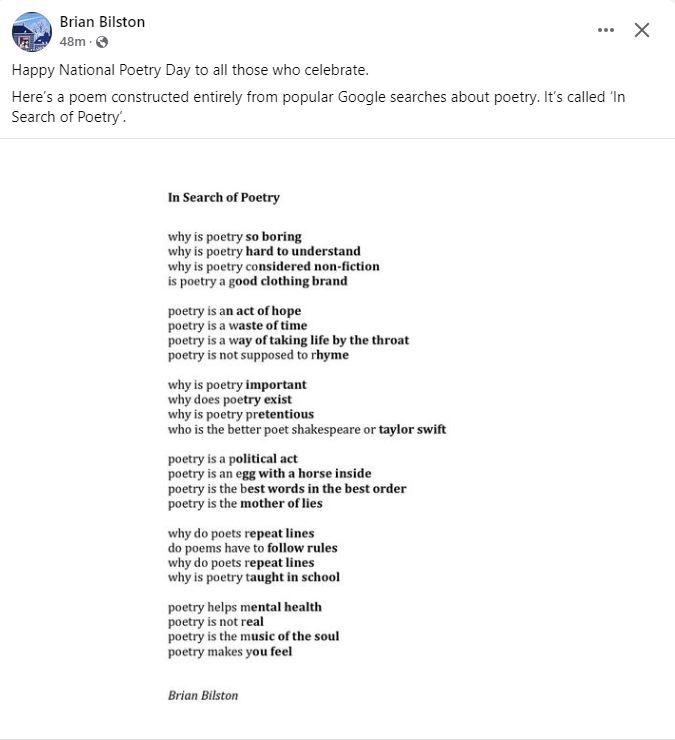

Extra goodies for National Poetry Day:

Follow Brian Bilston to add a bit of joy to your feed.

Editor Rosie Storey Hilton announces a poetry anthology Saraband are going to be releasing later this month, Green Verse: Poems for our Planet. I’ll hope to review it soon.

Two poems that have been taking the top of my head off recently (in Emily Dickinson’s phrasing), from Poetry Unbound (left) and Seamus Heaney’s Field Work:

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

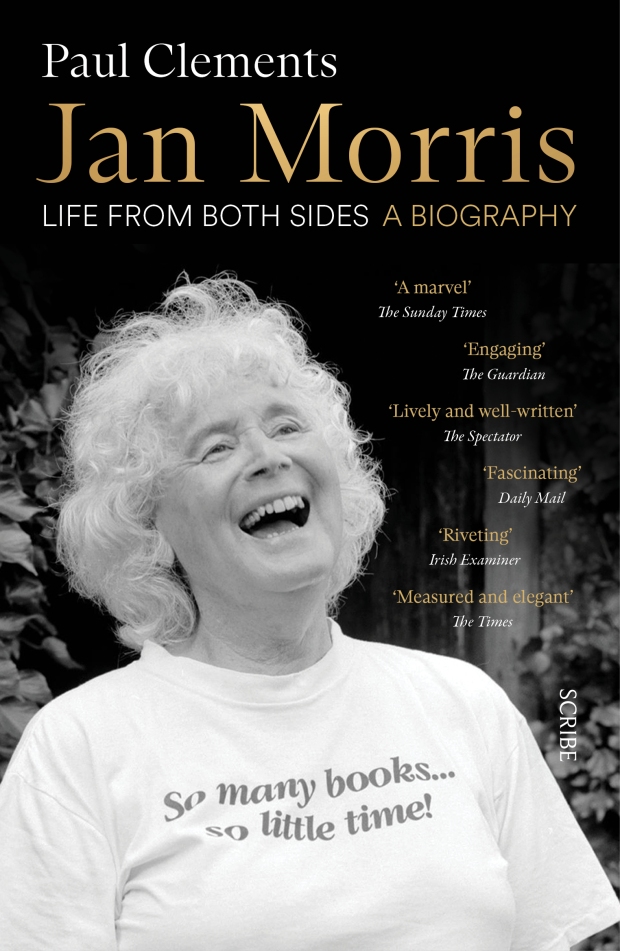

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

This was among my

This was among my  All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!) This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

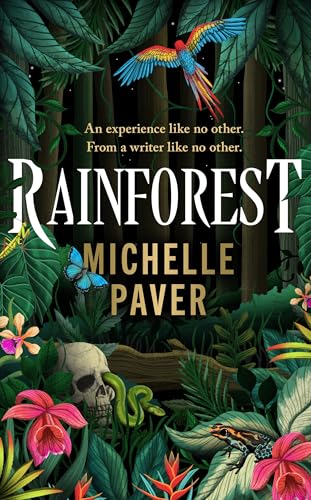

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues. I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (

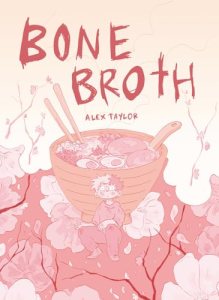

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults ( Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

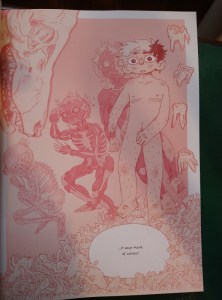

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it. This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

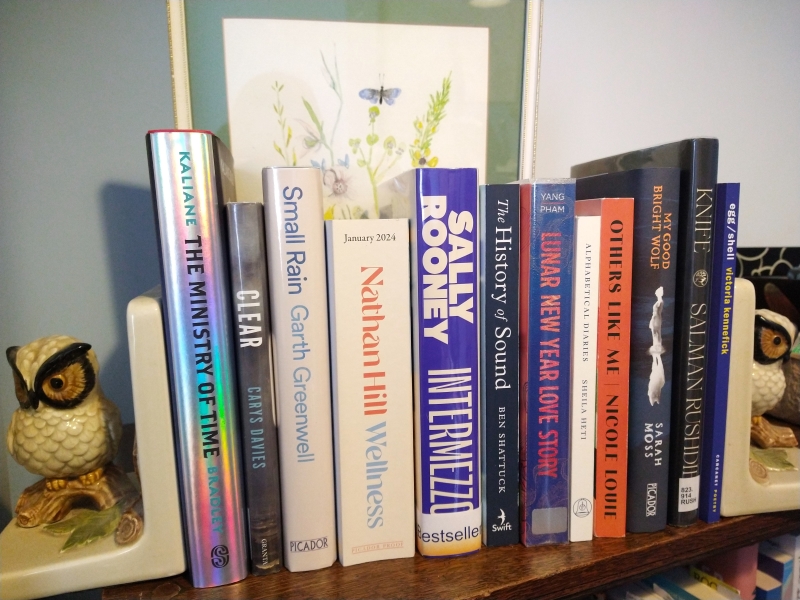

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages] After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,

I was blown away by Kennefick’s 2021 debut,  This is Mann’s second collection, after

This is Mann’s second collection, after

My second collection by Bloom this year, after

My second collection by Bloom this year, after  “After” has a school leaver partying and figuring out what comes next, “Ontario” revolves around a trip to Canada, and “Arianespace” has an investigator visiting an elderly woman who has reported a UFO sighting. The longest story (billed as a novella), “Mustang,” focuses on a French family that has relocated to Colorado in the 1990s. The mother, recently bereaved, learns to drive their rather impractical American car.

“After” has a school leaver partying and figuring out what comes next, “Ontario” revolves around a trip to Canada, and “Arianespace” has an investigator visiting an elderly woman who has reported a UFO sighting. The longest story (billed as a novella), “Mustang,” focuses on a French family that has relocated to Colorado in the 1990s. The mother, recently bereaved, learns to drive their rather impractical American car.