Love Your Library, June 2025

Thank you, as always, to Eleanor, who has put up multiple posts about her recent library reading. My thanks also go to Skai for participating again. Marcie has been taking part in the Toronto Public Library reading challenge Bingo card. I enjoyed seeing in Molly Wizenberg’s latest Substack that she and her child are both doing the Seattle Public Library Summer Book Bingo. I’ve never joined my library system’s adult summer reading challenge because surely it’s meant for non-regular readers. You can sign up to win a prize if you read five or more books – awwww! – and it just wouldn’t seem fair for me to participate.

It’s Pride Month and my library has displays up for it, of course. I got to attend the first annual Queer Folk Festival in London as an ally earlier this month and it was great fun!

Two current initiatives in my library system are pop-up libraries in outlying villages, and a quiet first hour of opening each weekday, meant to benefit those with sensory needs. I volunteer in the first two hours on Tuesdays but haven’t yet noticed lower lighting or it being any quieter than usual.

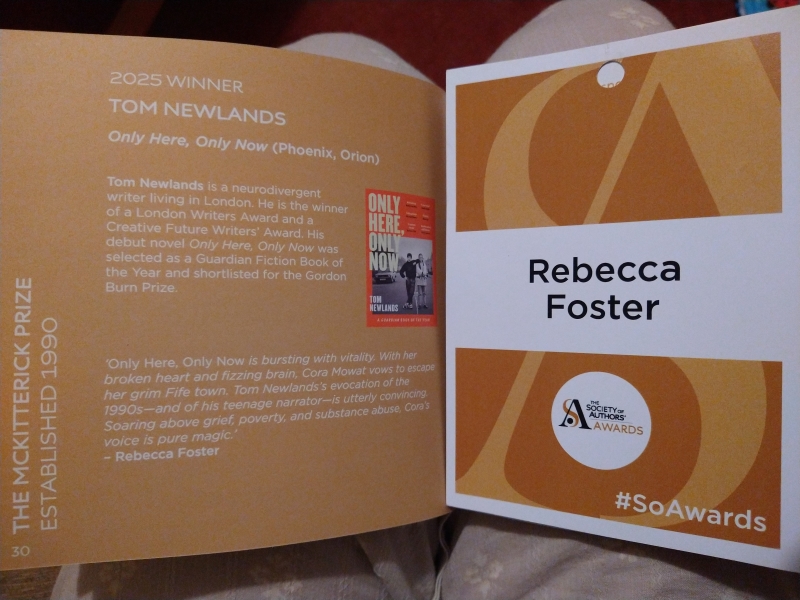

At the Society of Authors Awards ceremony, Joseph Coelho mentioned that during his time as Waterstones Children’s Laureate, he joined 217 libraries around the country to support their work! (He also built a bicycle out of bamboo and rode it around the south coast.)

I enjoyed this satirical article on The Rumpus about ridding libraries of diversity and inclusion practices. My favourite line: “The ‘Diverse Discussions’ book club will be renamed ‘Not Woke Folk (Tales).’”

And finally, I discovered evidence of my first bout of library volunteering (in Bowie, Maryland, for a middle school requirement) in my mother’s journal entry from 20 April 1996: “Rebecca started her Community Service this a.m., 10 – 12 noon, at the Library. She learned to put children’s books on the cart by sorting them.”

My library use over the last month:

(links are to books not already reviewed on the blog)

READ

- Good Girl by Aria Aber

- Moving the Millers’ Minnie Moore Mine Mansion by Dave Eggers

- Self-Portrait with Family by Amaan Hyder

- May Day by Jackie Kay

- Spring: The Story of a Season by Michael Morpurgo

- The Age of Diagnosis: Sickness, Health and Why Medicine Has Gone Too Far by Suzanne O’Sullivan

SKIMMED

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working for You by Maisie Hill

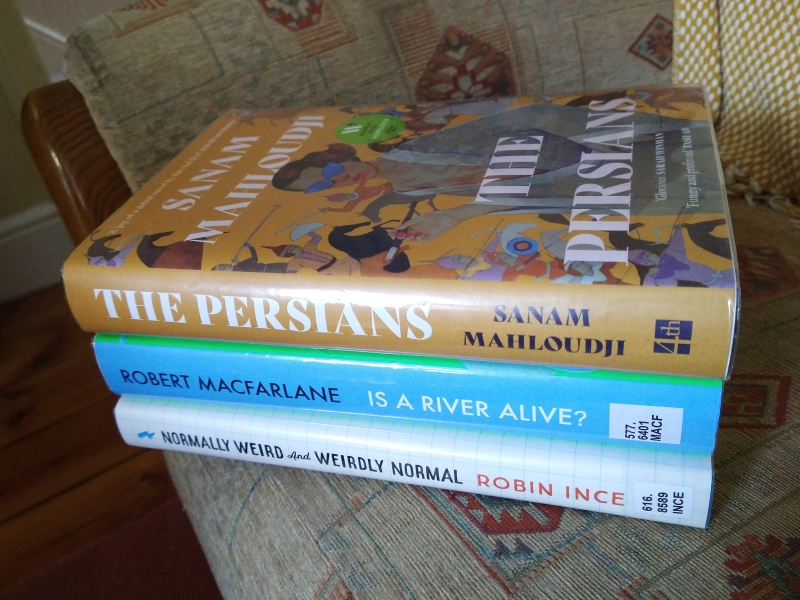

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane

CURRENTLY READING

- Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion by Lamorna Ash

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Bellies by Nicola Dinan

- To the Edge of the Sea: Schooldays of a Crofter’s Child by Christina Hall

- The Secret Lives of Booksellers and Librarians: True Stories of the Magic of Reading by James Patterson & Matt Eversmann

- Ripeness by Sarah Moss

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Fulfillment by Lee Cole

- Adam by Gboyega Odubanjo

- The Forgotten Sense: The Nose and the Perception of Smell by Jonas Olofsson

- Enchanted Ground: Growing Roots in a Broken World by Steven Lovatt

- Boiled Owls by Azad Ashim Sharma

- The Artist by Lucy Steeds

+ various Berlin and Germany guides to plan a September trip

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Most by Jessica Anthony

- Atmosphere by Taylor Jenkins Reid

- Three Weeks in July by Adam Wishart & James Nally

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Terrible Horses by Raymond Antrobus

- The Interpretation of Cats: And Their Owners by Claude Béata; translated by David Watson

- The Boy, the Troll and the Chalk by Anne Booth (whom I met at the SoA Awards ceremony)

- The Husbands by Holly Gramazio

- Albion by Anna Hope

- Fragile Minds by Bella Jackson

- The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce

- The Names by Florence Knapp

- Shattered by Hanif Kureishi

- Wife by Charlotte Mendelson

- The Eights by Joanna Miller

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal: My Adventures in Neurodiversity by Robin Ince – His rambling stories work better in person (I really enjoyed seeing him in Hungerford on the tour promoting this book) than in print. I read about 66 pages.

- The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji – I only read the first few pages of this Women’s Prize shortlistee and it seemed flippant and unnecessary.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Day by Michael Cunningham – I’ll get it back out another time.

- Looking After: A Portrait of My Autistic Brother by Caroline Elton – This was requested off of me; I might get it back out another time.

- Rebel Bodies: A Guide to the Gender Health Gap Revolution by Sarah Graham – I lost interest and needed to make space on my card.

- The Kingdoms by Natasha Pulley – I thought I’d try this because it has an Outer Hebrides setting, but I couldn’t get into the first few pages and didn’t want to pack a chunky paperback that might not work out for me.

- Horse by Rushika Wick – I needed to make space on my card plus this didn’t really look like my sort of poetry.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

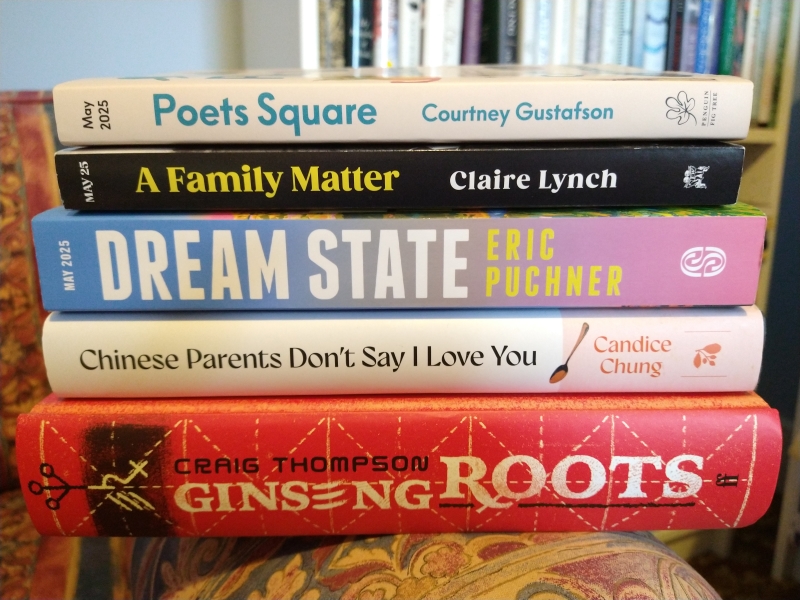

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Three on a Theme for Father’s Day: Holt Poetry, Filgate & Virago Anthologies

A rare second post in a day for me; I got behind with my planned cat book reviews. I happen to have had a couple of fatherhood-themed books come my way earlier this year, an essay anthology and a debut poetry collection. To make it a trio, I finished an anthology of autobiographical essays about father–daughter relationships that I’d started last year.

What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, ed. Michele Filgate (2025)

This follow-up to Michele Filgate’s What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About is an anthology of 16 compassionate, nuanced essays probing the intricacies of family relationships.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Some take the title brief literally: Heather Sellers dares to ask her father about his cross-dressing when she visits him in a nursing home; Nayomi Munaweera is pleased her 82-year-old father can escape his arranged marriage, but the domestic violence that went on in it remains unspoken. Tomás Q. Morín’s “Operation” has the most original structure, with the board game’s body parts serving as headings. All the essays display psychological insight, but Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s—contrasting their father’s once-controlling nature with his elderly vulnerability—is the pinnacle.

Despite the heavy topics—estrangement, illness, emotional detachment—these candid pieces thrill with their variety and their resonant themes. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness. (The above is my unedited version.)

Father’s Father’s Father by Dane Holt (2025)

Holt’s debut collection interrogates masculinity through poems about bodybuilders and professional wrestlers, teenage risk-taking and family misdemeanours.

Your father’s father’s father

poisoned a beautiful horse,

that’s the story. Now you know this

you’ve opened the door marked

‘Family History’.

(from “‘The Granaries are Bursting with Meal’”)

The only records found in my grandmother’s attic

were by scorned women for scorned women

written by men.

(from “Tammy Wynette”)

He writes in the wake of the deaths of his parents, which, as W.S. Merwin observed, makes one feel, “I could do anything,” – though here the poet concludes, “The answer can be nothing.” Stylistically, the collection is more various than cohesive, with some of the late poetry as absurdist as you find in Caroline Bird’s. My favourite poem is “Humphrey Bogart,” with its vision of male toughness reinforced by previous generations’ emotional repression:

My grandfather

never told his son that he loved him.

I said this to a group of strangers

and then said, Consider this:

his son never asked to be told.

They both loved

the men Humphrey Bogart played.

…

There was

one thing my grandfather could

not forgive his son for.

Eventually it was his son’s dying, yes.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen (1983; 1994)

“I doubt if my father will ever lose his power to wound me, and yet…”

~Eileen Fairweather

I read the introduction and first seven pieces (one of them a retelling of a fairy tale) last year and reviewed that first batch here. Some common elements I noted in those were service in a world war, Freudian interpretation, and the alignment of the father with God. The writers often depicted their fathers as unknown, aloof, or as disciplinarians. In the remainder of the book, I particularly noted differences in generations and class. Father and daughter are often separated by 40–55 years. The men work in industry; their daughters turn to academia. Her embrace of radicalism or feminism can alienate a man of conservative mores.

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

I mostly skipped over the quotes from novels and academic works printed between the essays. There are solid pieces by Adrienne Rich, Michèle Roberts, Sheila Rowbotham, and Alice Walker, but Alice Munro knocks all the other contributors into a cocked hat with “Working for a Living,” which is as detailed and psychologically incisive as one of her stories (cf. The Beggar Maid with its urban/rural class divide). Her parents owned a fox farm but, as it failed, her father took a job as night watchman at a factory. She didn’t realize, until one day when she went in person to deliver a message, that he was a janitor there as well.

This was a rewarding collection to read and I will keep it around for models of autobiographical writing, but it now feels like a period piece: the fact that so many of the fathers had lived through the world wars, I think, might account for their cold and withdrawn nature – they were damaged, times were tough, and they believed they had to be an authority figure. Things have changed, somewhat, as the Filgate anthology reflects, though father issues will no doubt always be with us. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop)

#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Literary Wives Club: The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham (1927)

As far as I know, this is the first play we’ve chosen for the club. While I’m a Maugham fan, I haven’t read him in a while and I’ve never explored his work for the theatre. The Constant Wife is a straightforward three-act play with one setting: a large parlour in the Middletons’ home in Harley Street, London. A true drawing room comedy, then, with very simple staging.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER}

Rumours are circulating that surgeon John Middleton has been having an affair with his wife Constance’s best friend, Marie-Louise. It’s news to Mrs. Culver and Martha, Constance’s mother and sister – but not to Constance herself. Mrs. Culver, the traditional voice of a previous generation, opines that men are wont to stray and so long as the wife doesn’t find out, what harm can it do? Women, on the other hand, are “naturally faithful creatures and we’re faithful because we have no particular inclination to be anything else,” she says.

Other characters enter in twos and threes for gossip and repartee and the occasional confrontation. Marie-Louise’s husband, Mortimer Durham, shows up fuming because he’s found John’s cigarette-case under her pillow and assumes it can only mean one thing. Constance is in the odd position of defending her husband’s and best friend’s honour, even though she knows full well that they’re guilty. With her white lies, she does them the kindness of keeping their indiscretion quiet – and gives herself the moral upper hand.

Constance is matter of fact about the fading of romance. She is grateful to have had a blissful first five years of marriage; how convenient that both she and John then fell out of love with each other at the same time. The decade since has been about practicalities. Thanks to John, she has a home, respectability, and fine belongings (also a child, only mentioned in passing); why give all that up? She’s still fond of John, anyway, and his infidelity has only bruised her vanity. However, she wants more from life, and a sheepish John is inclined to give her whatever she asks. So she agrees to join an acquaintance’s interior decorating business.

The early reappearance of her old flame Bernard Kersal, who is clearly still smitten with her, seeds her even more daring decision in the final act, set one year after the main events. Having earned £1400 of her own money, she has more than enough to cover a six-week holiday in Italy. She announces to John that she’s deposited the remainder in his account “for my year’s keep,” and slyly adds that she’ll be travelling with Bernard. This part turns out to be a bluff, but it’s her way of testing their new balance of power. “I’m not dependent on John. I’m economically independent, and therefore I claim my sexual independence,” she declares in her mother’s company.

There are some very funny moments in the play, such as when Constance tells her mother she’ll place a handkerchief on the piano as a secret sign during a conversation. Her mother then forgets what it signifies and Constance ends up pulling three hankies in a row from her handbag. I had to laugh at Mrs. Culver’s test for knowing whether you’re in love with someone: “Could you use his toothbrush?” It’s also amusing that Constance ends up being the one to break up with John for Marie-Louise, and with Marie-Louise for John.

However, there are also hidden depths of feeling meant to be brought out by the actors. At least three times in scenes between John and Constance, I noted the stage direction “Breaking down” in parentheses. The audience, therefore, is sometimes privy to the emotion that these characters can’t express to each other because of their sardonic wit and stiff upper lips.

I hardly ever experience plays, so this was interesting for a change. At only 70-some pages, it’s a quick read even if a bit old-fashioned or tedious in places. It does seem ahead of its time in questioning just what being true to a spouse might mean. A clever and iconoclastic comedy of manners, it’s a pleasant waystation between Oscar Wilde and Alan Ayckbourn.

(Free download from Internet Archive – is this legit or a copyright scam??) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Answered by means of quotes from Constance.

- Partnership is important, yes, but so is independence. (Money matters often crop up in the books we read for the club.)

“there is only one freedom that is really important, and that is economic freedom”

- Marriage often outlasts the initial spark of lust, and can survive one or both partners’ sexual peccadilloes. (Maugham, of course, was a closeted homosexual married to a woman.)

“I am tired of being the modern wife.” When her mother asks for clarification, she adds rather bluntly, “A prostitute who doesn’t deliver the goods.”

“I may be unfaithful, but I am constant. I always think that’s my most endearing quality.”

We have a new member joining us this month: Becky, from Australia, who blogs at Aidanvale. Welcome! Here’s the group’s page on Kay’s website.

See Becky’s, Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Novel about My Wife by Emily Perkins

May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

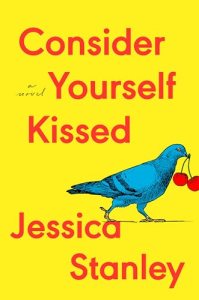

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

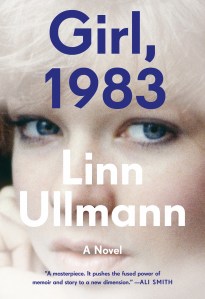

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

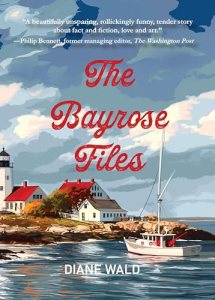

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research?

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research? The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project.

The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project. The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

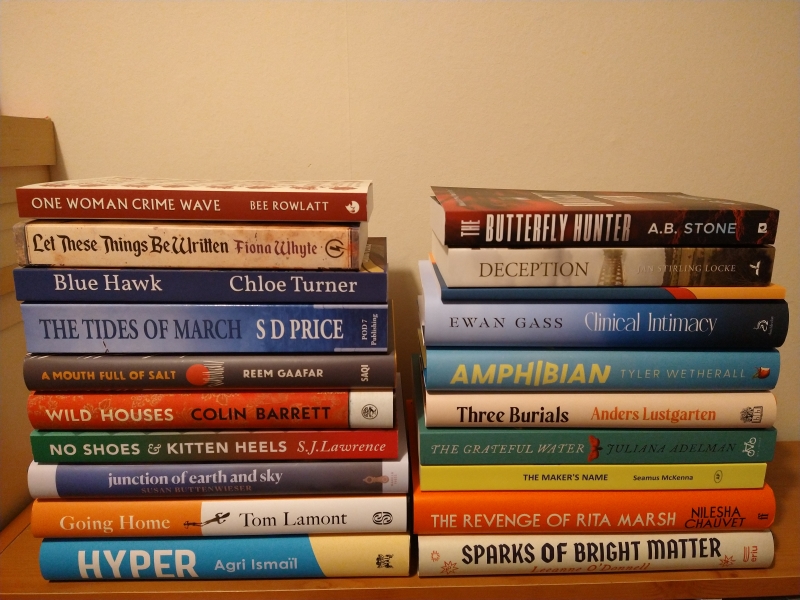

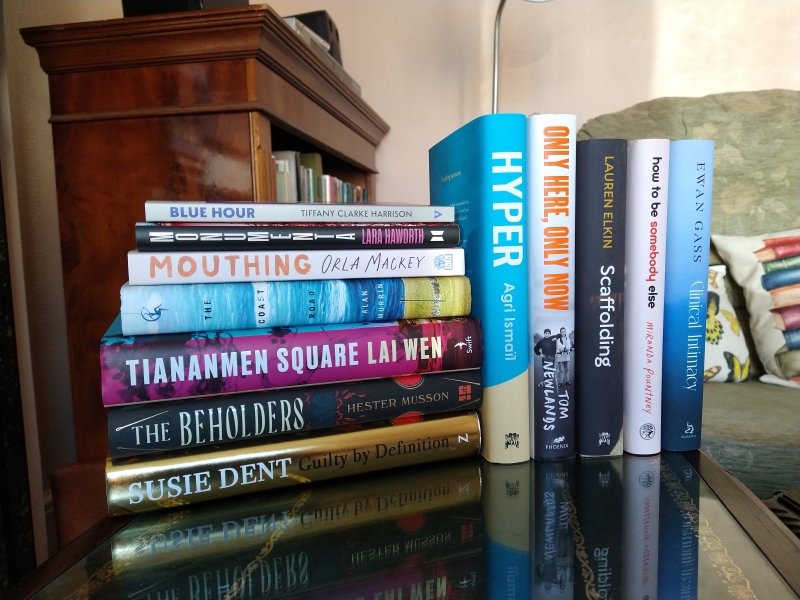

The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”. Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

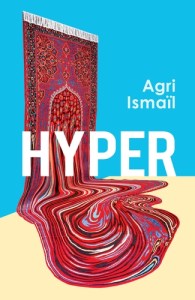

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

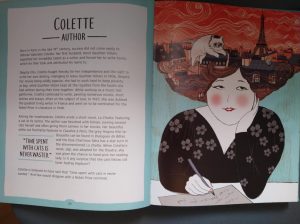

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

Last year I read the previous book,

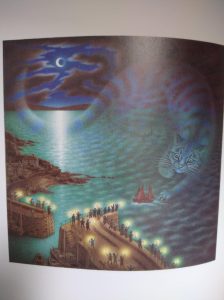

Last year I read the previous book,  The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)