#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

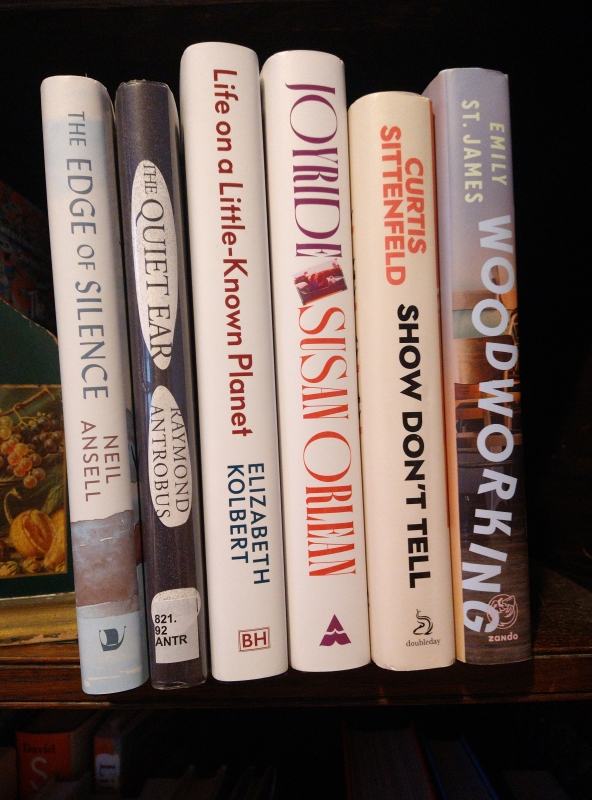

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

September Releases, Part II: Antrobus, Attenberg, Strout and More

As promised yesterday, I give excerpts of the six (U.S.) September releases I reviewed for Shelf Awareness. But first, my thoughts on a compassionate sequel about a beloved ensemble cast.

Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth Strout

“People always tell you who they are if you just listen”

Alternative title ideas: “Oh Bob!” or “Talk Therapy in Small-Town Maine.” I’ve had a mixed experience with the Amgash novels, of which I’ve now read four. Last year’s Lucy by the Sea was my favourite, a surprisingly successful Covid novel with much to say about isolation, political divisions and how life translates into art. Oh William!, though shortlisted for the Booker, seemed a low point. It’s presented as Lucy’s published memoir about her first husband, but irked me with its precious, scatter-brained writing. For me, Tell Me Everything was closer to the latter. It continues Strout’s newer habit of bringing her various characters together in the same narrative. That was a joy of the previous book, but here it’s overdone and, along with the knowing first-person plural narration (“As we mentioned earlier, housing prices in Crosby, Maine, had been going through the roof since the pandemic”; “Oh Jim Burgess! What are we to do with you?”), feels affected and hokey.

Strout makes it clear from the first line that this novel will mostly be devoted to Bob Burgess, who is not particularly interesting but perhaps a good choice of protagonist for that reason. A 65-year-old semi-retired lawyer, he’s a man of integrity who wins confidences because of his unassuming mien and willingness to listen and help where he can. One doesn’t read Strout for intrigue, but there is actually a mild murder mystery here. Bob ends up defending Matt Beach, a middle-aged man suspected of disposing of his mother’s body in a quarry. The Beaches are odd and damaged, with trauma threading through their history.

Sad stories are indeed the substance of the novel; Lucy trades in them. Literally: on her visits to Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home room, they swap bleak stories of the “unrecorded lives” they have observed or heard about. Lucy and Bob, who are clearly in love with each other, keep up a similar exchange of gloomy tales on their regular walks. Lucy asks Bob and Olive the point of these anecdotes, pondering the very meaning of life. Bob dismisses the question as immature; “as we have said, Bob was not a reflective fellow.” And because the book is filtered through Bob, we, too, feel this is just a piling up of depressing stories. Why should I care about Bob’s ex-wife’s alcoholism, his sister-in-law’s death from cancer, his nephew’s accident? Or any of the other unfortunate occurrences that make up a life. Bob and Lucy are appealingly ordinary characters, yet Strout suggests that they function as secular “sin-eaters,” accepting confessions. Forasmuch as they focus on others, they do each come to terms with childhood trauma and the reality of their marriages. Strout majors on emotional intelligence, but can be clichéd and soundbite-y. Such was my experience of this likable but diffuse novel.

With thanks to Viking (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

Poetry:

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus – The British-Jamaican poet’s intimate third collection contrasts the before and after of becoming a father—a transition that prompts him to reflect on his Deaf and biracial identity as well as the loss of his own father.

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus – The British-Jamaican poet’s intimate third collection contrasts the before and after of becoming a father—a transition that prompts him to reflect on his Deaf and biracial identity as well as the loss of his own father.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor – Factor’s long, intricate second poetry collection envisions womanhood as a tug of war between desire and constraint. “Elegy for a Younger Self” poems string together vivid reminiscences.

Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor – Factor’s long, intricate second poetry collection envisions womanhood as a tug of war between desire and constraint. “Elegy for a Younger Self” poems string together vivid reminiscences.

Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa – The Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate’s debut collection is a tender chronicle of the years leading to his mother’s death from cancer. Food and nature imagery chart the decline in Nkoli’s health and its effect on her family.

Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa – The Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate’s debut collection is a tender chronicle of the years leading to his mother’s death from cancer. Food and nature imagery chart the decline in Nkoli’s health and its effect on her family.

Fiction:

A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg – Her tenth book evinces her mastery of dysfunctional family stories. From the Chicago-area Cohens, the circle widens and retracts as partners and friends enter and exit. Through estrangement and reunion, as characters grapple with sexuality and addictions, the decision is between hiding and figuring out who they are.

A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg – Her tenth book evinces her mastery of dysfunctional family stories. From the Chicago-area Cohens, the circle widens and retracts as partners and friends enter and exit. Through estrangement and reunion, as characters grapple with sexuality and addictions, the decision is between hiding and figuring out who they are.

Nonfiction:

We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood by Jennifer Case – Case’s second book explores the evolution, politics, and culture of contemporary parenthood in 15 intrepid essays. Science and statistics weave through in illuminating ways. This forthright, lyrical study of maternity is an excellent companion read to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence.

We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood by Jennifer Case – Case’s second book explores the evolution, politics, and culture of contemporary parenthood in 15 intrepid essays. Science and statistics weave through in illuminating ways. This forthright, lyrical study of maternity is an excellent companion read to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence.

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan – Ten years after his Booker Prize win for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan revisits his father’s time as a POW—the starting point but ultimately just one thread in this astonishing and uncategorizable work that combines family memoir, biography, and history to examine how love and memory endure. (Published in the USA on 17 September.)

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan – Ten years after his Booker Prize win for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan revisits his father’s time as a POW—the starting point but ultimately just one thread in this astonishing and uncategorizable work that combines family memoir, biography, and history to examine how love and memory endure. (Published in the USA on 17 September.)

With thanks to Emma Finnigan PR and Vintage (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Any other September releases you’d recommend?

Recent Poetry Releases by Allison Blevins, Kit Fan, Lisa Kelly and Laura Scott

I’m catching up on four 2023 poetry collections from independent publishers, three of them from Carcanet Press, which so graciously keeps me stocked up with work by contemporary poets. Despite the wide range of subject matter, style and technique, nature imagery and erotic musings are links. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

Cataloguing Pain by Allison Blevins

Last year I reviewed Allison Blevins’ Handbook for the Newly Disabled. This shares its autobiographical consideration of chronic illness and queer parenting. Specifically, she looks back to her MS diagnosis and three IVF pregnancies, and her spouse’s transition. Both partners were undergoing bodily transformations and coming into new identities, the one as disabled and the other as a man. In later poems she calls herself “The shell”, while “Elegy for My Wife,” which closes Part I, makes way for references to “my husband” in Part II.

Last year I reviewed Allison Blevins’ Handbook for the Newly Disabled. This shares its autobiographical consideration of chronic illness and queer parenting. Specifically, she looks back to her MS diagnosis and three IVF pregnancies, and her spouse’s transition. Both partners were undergoing bodily transformations and coming into new identities, the one as disabled and the other as a man. In later poems she calls herself “The shell”, while “Elegy for My Wife,” which closes Part I, makes way for references to “my husband” in Part II.

“I won’t wail for your dead name. I don’t mean that violence. I wish for a word other than elegy to explain how some of this feels like goodbye.”

In unrhymed couplets or stanzas and bittersweet paragraphs, Blevins marshals metaphors from domestic life – colours, food, furniture, gardening – to chart the changes that pain and disability force onto their family’s everyday routines. “Fall Risk” and “Fly Season” are particular highlights. This is a potent and frankly sexual text for readers drawn to themes of health and queer family-making (see also my Three on a Theme post on that topic).

Published by YesYes Books on 19 April. With thanks to the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Ink Cloud Reader by Kit Fan

Kit Fan was raised in Hong Kong and moved to the UK as an adult. This is his third collection of poetry. “Suddenly” tells a version of his life story in paragraphs or single lines that all incorporate the title word (with an ironic nod, through the epigraph, to Elmore Leonard’s writing ‘rule’ that “suddenly” should never be used). The “IF” statements of “Delphi” then ponder possible future events; a trip to hospital sees him contemplating his mortality (“Glück,” written as a miniature three-act play) and appreciating tokens of beauty (“Geraniums in May”). “Yew,” unusually, is a modified sonnet where every line rhymes.

Kit Fan was raised in Hong Kong and moved to the UK as an adult. This is his third collection of poetry. “Suddenly” tells a version of his life story in paragraphs or single lines that all incorporate the title word (with an ironic nod, through the epigraph, to Elmore Leonard’s writing ‘rule’ that “suddenly” should never be used). The “IF” statements of “Delphi” then ponder possible future events; a trip to hospital sees him contemplating his mortality (“Glück,” written as a miniature three-act play) and appreciating tokens of beauty (“Geraniums in May”). “Yew,” unusually, is a modified sonnet where every line rhymes.

As the collection’s title suggests, it is equally interested in the natural and the human. There are poems describing the cycles of the moon (the lines of “Moon Salutation” curve into a half-moon parabola) and the wind. Ink pulls together calligraphy, the Chinese zodiac and literature. “The Art of Reading,” which commemorates important moments, real and imaginary, of the poet’s reading life, was a favourite of mine, as was “Derek Jarman’s Garden.” Fan also writes of memory and travels – including to the underworld. His relationship with his husband is a subtle background subject. (“Even though we’ve lived together for nearly twenty years and are always reading sometimes I can’t read you at all which I guess is a good thing”). It’s an opulent and allusive work that has made me eager to try more by Fan. Luckily, I have his debut novel (passed on to me by Laura T.) on the shelf.

Readalike: Moving House by Theophilus Kwek

Published on 27 April. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly

Lisa Kelly’s concern with deafness is sure to bring to mind Raymond Antrobus and Ilya Kaminsky, but I prefer her work. Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and in Part I of this second collection, entitled “Chamber,” her poems engage with questions of split identity:

Lisa Kelly’s concern with deafness is sure to bring to mind Raymond Antrobus and Ilya Kaminsky, but I prefer her work. Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and in Part I of this second collection, entitled “Chamber,” her poems engage with questions of split identity:

Is this what it is like for us all? Always having to relearn home

with a strange tongue and alien hands, prepared to open our mouths

as if to beg, to touch tongue-tip with fingertip to reveal ourselves?

The title poem relishes the absurdities of telephone communication, closing with:

In the House of the Interpreter,

Oralism and Manualism, like Passion and Patience,

are rewarded differently and at different times.

Hello, this is your Interpreter. What is your wishlist?

This section ends with “#WhereIsTheInterpreter,” about the Deaf community’s outrage that the Prime Minister’s Covid briefings were not simultaneously translated into BSL.

Bizarrely but delightfully, Kelly then moves onto “Oval Window,” a sequence of alliteration-rich poems about fungi. “Mycology Abecedarian” is a joyful list of species’ common names, while “Mycelium” notes how mushrooms show that different ways of evolution and reproduction are possible. “Darning Mushroom” even combines images of fungi and holey socks. Part III, “Canal,” is a miscellany of autobiographical poems and homages to Faith Ringgold, full of references to colour, language, nature and travel.

Readalike: In the Quaker Hotel by Helen Tookey

Published on 27 April. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Fourth Sister by Laura Scott

Back in 2019 I reviewed Laura Scott’s debut collection, So Many Rooms. Her second book reflects some of the same preoccupations: art, birds, colour and Russian literature. Chekhov is a recurring point of reference across the two; here, for instance, we have a found poem composed of excerpts from his letters. Scott also writes about the deaths of her parents, voicing resentment towards her father and remarking on life’s irony. As the title suggests, her family constellation includes sisters. Her godparents loom surprisingly large; her godmother was, apparently, a spy. My favourite of the poems, “Still Life,” imagines the whole of life being prized as a glass in an exhibit, appealingly pristine and praiseworthy in comparison to what we usually perceive: “the raggy sprawl of a life … the wrong turns and longing of it.” Elsewhere, metaphors are drawn from the theatre: performing lines, taking items from a wardrobe. I loved the way the pull of nostalgia is set up in opposition to the now.

Back in 2019 I reviewed Laura Scott’s debut collection, So Many Rooms. Her second book reflects some of the same preoccupations: art, birds, colour and Russian literature. Chekhov is a recurring point of reference across the two; here, for instance, we have a found poem composed of excerpts from his letters. Scott also writes about the deaths of her parents, voicing resentment towards her father and remarking on life’s irony. As the title suggests, her family constellation includes sisters. Her godparents loom surprisingly large; her godmother was, apparently, a spy. My favourite of the poems, “Still Life,” imagines the whole of life being prized as a glass in an exhibit, appealingly pristine and praiseworthy in comparison to what we usually perceive: “the raggy sprawl of a life … the wrong turns and longing of it.” Elsewhere, metaphors are drawn from the theatre: performing lines, taking items from a wardrobe. I loved the way the pull of nostalgia is set up in opposition to the now.

Published on 23 February. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (#NovNov Nonfiction Buddy Read)

For nonfiction week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (1903). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Keller’s story is culturally familiar to us, perhaps from the William Gibson play The Miracle Worker, but I’d never read her own words. She was born in Alabama in 1880; her father had been a captain in the Confederate Army. An illness (presumed to be scarlet fever) left her blind and deaf at the age of 19 months, and she describes herself in those early years as mischievous and hot-tempered, always frustrated at her inability to express herself. The arrival of her teacher, Anne Sullivan, when Helen was six years old transformed her “silent, aimless, dayless life.”

I was fascinated by the glimpses into child development and education. Especially after she learned Braille, Keller loved books, but she believed she learned just as much from nature: “everything that could hum or buzz, or sing, or bloom, had a part in my education.” She loved to sit in the family orchard and would hold insects or fossils and track plant and tadpole growth. Her first trip to the ocean (Chapter 10) was a revelation, and rowing and sailing became two of her chief hobbies, along with cycling and going to the theatre and museums.

At age 10 Keller relearned to speak – a more efficient way to communicate than her usual finger-spelling. She spent winters in Boston and eventually attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in preparation for starting college at Radcliffe. Her achievements are all the more remarkable when you consider that smell and touch – senses we tend to overlook – were her primary ones. While she used a typewriter to produce schoolwork, a teacher spelling into her hand was still her main way to intake knowledge. Specialist textbooks for mathematics and multiple languages were generally not available in Braille. Digesting a lesson and completing homework thus took her much longer than it did her classmates, but still she felt “impelled … to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear.”

It was surprising to find, at the center of the book, a detailed account of a case of unwitting plagiarism (Chapter 14). Eleven-year-old Keller wrote a story called “The Frost King” for a beloved teacher at the Perkins Institution for the Blind. He was so pleased that he printed it in one of their publications, but it soon came to his attention that the plot was very similar to “The Frost Fairies” in Birdie and His Friends by Margaret T. Canby. The tale must have been read to Keller long ago but become so deeply buried in the compost of a mind’s memories that she couldn’t recall its source. Some accused Keller and Sullivan of conspiring, and this mistrust more than the incident itself cast a shadow over her life for years to come. I was impressed by Keller discussing in depth something that it would surely have been more comfortable to bury. (I’ve sometimes had the passing thought that if I wrote a memoir I would structure it around my regrets or most embarrassing moments. Would that be penance or masochism?)

This short memoir was first serialized in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Keller was only 23 and partway through her college degree at the time of publication. An initial chronological structure later turns more thematic and the topics are perhaps a little scattershot. I would attribute this, at least in part, to the method of composition: it would be difficult to make large-scale edits on a manuscript because everything she typed had to be spelled back to her for approval. Minor line edits would be easy enough, but not big structural changes. (I wonder if it’s similar with work that’s been dictated, like May Sarton’s later journals.)

Helen Keller in graduation cap and gown. (PPOC, Library of Congress. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Keller went on to write 12 more books. It would be interesting to follow up with another one to learn about her travels and philanthropic work. For insight into a different aspect of her life – bearing in mind that it’s fiction – I recommend Helen Keller in Love by Rosie Sultan. In a couple of places Keller mentions Laura Bridgman, her less famous predecessor in the deaf–blind community; Kimberly Elkins’ 2014 What Is Visible is a stunning novel about Bridgman.

For such a concise book – running to just 75 pages in my Dover Thrift Editions paperback – this packs in so much. Indeed, I’ve found more to talk about in this review than I might have expected. The elements that most intrigued me were her early learning about abstractions like love and thought, and her enthusiastic rundown of her favorite books: “In a word, literature is my Utopia. Here I am not disenfranchised. No barrier of the senses shuts me out from the sweet, gracious discourse of my book-friends.”

It’s possible some readers will find her writing style old-fashioned. It would be hard to forget you’re reading a work from nearly 120 years ago, given the sentimentality and religious metaphors. But the book moves briskly between anecdotes, with no filler. I remained absorbed in Keller’s story throughout, and so admired her determination to obtain a quality education. I know we’re not supposed to refer to disabled authors’ work as “inspirational,” so instead I’ll call it both humbling and invigorating – a reminder of my privilege and of the force of the human will. (Secondhand purchase, Barter Books)

Also reviewed by:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,

Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,  There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”:

There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”: There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?)

There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?) In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer.

In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer. This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,

This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,  Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes.

Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes.

My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog.

My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog.

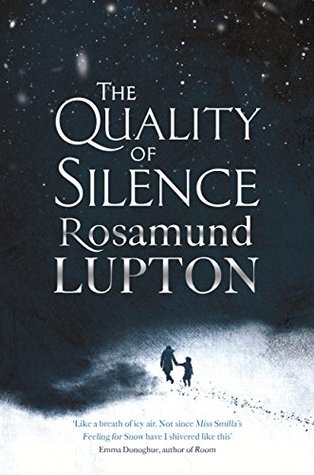

Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent.

Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent.

This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to

This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to