Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence and Find Him! (links to my Shelf Awareness reviews) are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

#NovNov25 Catch-Up: Dodge, Garner, O’Collins, Sagan and A. White

As promised, I’m catching up on five novella-length works I finished in November. In fiction, I have an odd duck of a family story, a piece of autofiction about caring for a friend with cancer, a record of an affair, and a tale of settling two new cats into home life in the 1950s. And in nonfiction, a short book about the religious approach to midlife crisis.

Fup by Jim Dodge (1983)

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages]

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages] ![]()

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (2008)

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages]

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages] ![]()

Second Journey: Spiritual Awareness and the Mid-Life Crisis by Gerald O’Collins SJ (1978; 1995)

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages]

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages] ![]()

A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan (1956)

[Translated from French by Irene Ash]

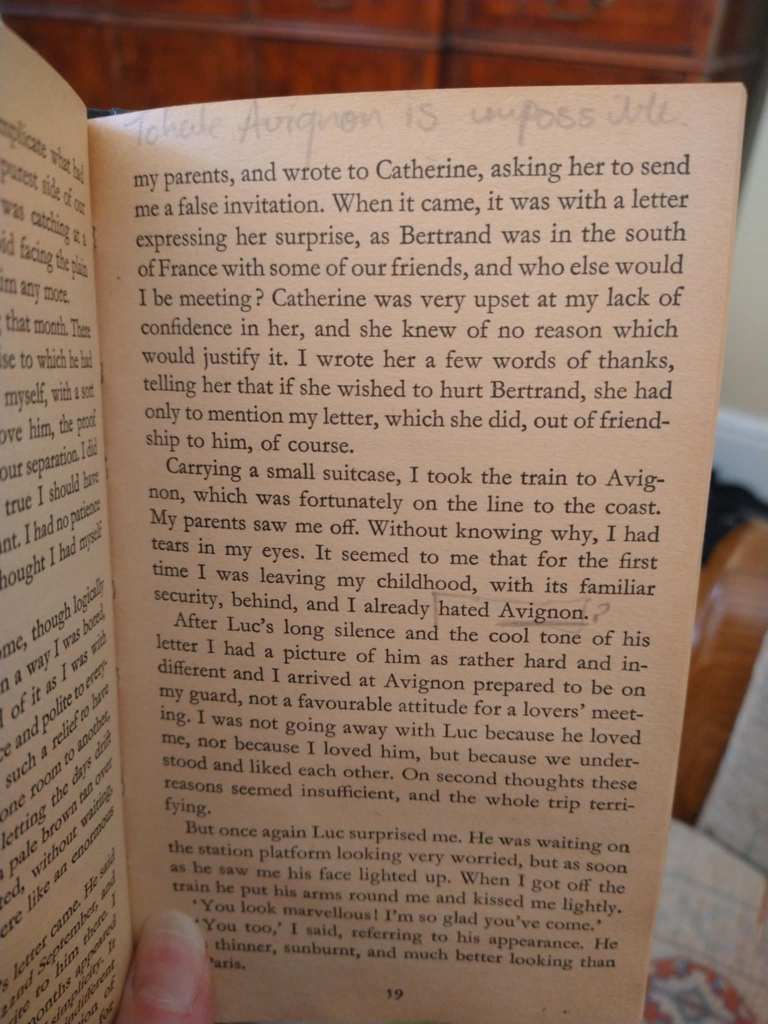

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages] ![]()

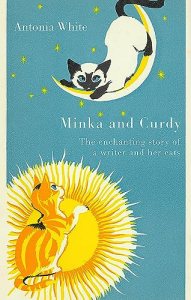

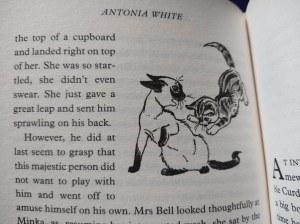

Minka and Curdy by Antonia White; illus. Janet and Anne Johnstone (1957)

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages]

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages] ![]()

I also had a few DNFs last month:

- The Book of Colour by Julia Blackburn (1995) seemed a good bet because I’ve enjoyed some of Blackburn’s nonfiction and it was on the Orange Prize shortlist. But after 60 pages I still had no idea what was going on amid the Mauritius-set welter of family history and magic realism. (Secondhand – Bas Books charity shop, 2022)

- A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood (1964) lured me because I’d so loved Goodbye to Berlin and I remember liking the Colin Firth film. But this story of an Englishman secretly mourning his dead partner while trying to carry on as normal as a professor in Los Angeles was so dreary I couldn’t persist. (Public library)

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel (2025) – JLS could write one of these mini nature volumes in his sleep. (Maybe he did with this one, actually?) I’d rather one full-length book from him every few years than bitty, redundant ones annually. (Public library)

- Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse (1974) – I’ve read one Jeeves & Wooster book before and enjoyed it well enough. This felt inconsequential, so as I already had way too many novellas on the go I sent it back whence it came. (Little Free Library)

Final statistics for #NovNov25 coming up tomorrow!

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler,” as Joe Hill said. Hard to believe, but it’s now the FIFTH year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogger/social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella is a book of 20,000 to 40,000 words, but because that’s hard for a reader to gauge, we tend to say anything under 200 pages (even nonfiction). I’m going to make it a personal challenge to limit myself to books of ~150 pages or less.

We’re keeping it simple this year with just the one buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey. (Though we chose it weeks ago, its shortlisting for the Booker Prize is all the more reason to read it!) The UK hardback has 144 pages. Here’s part of the blurb to entice you:

“Six astronauts rotate in their spacecraft above the earth. … Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. … They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?”

Please join us in reading it at any time between now and the end of November!

We won’t have any official themes or prompts, but you might want to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last NovNov, and finish it with a New to My TBR list based on what novellas others have tempted you to try in the future.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

“The Future of the Novella”

On the 11th, at Foyles in London, I attended a perfect event to get me geared up for Novellas in November. Indie publisher Weatherglass Books and judge Ali Smith introduced us to the two winners she chose for the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize: Kate Kruimink’s Astraea (set on a 19th-century Australian convict ship), out now, and Deborah Tomkins’ Aerth (a sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative earths), coming out in January.

Ali Smith

We heard readings from both novellas, and Neil Griffiths and Damian Lanigan of Weatherglass told us some more about what they publish and the process of reading the prize submissions (blind!). Lanigan called the novella “a form for our times” and put this down not just to modern attention spans but to focus – the glimpse of something essential. He and Smith mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald, Claire Keegan, Françoise Sagan and Muriel Spark as some of the masters of the novella form.

The effortlessly cool Smith spoke about the delight of spending weekend mornings – she writes during the week but gives herself the weekends off to read – in bed with a pot of coffee and a Weatherglass novella. She particularly enjoyed going into each book from the shortlist without any context and lamented that blurbs mean the story has to be, to some extent, given away to the reader. She said the ending of a novella has to land “like a cat, on its feet” (Griffiths then appended that it must also be ambiguous).

Kate Kruimink

Kruimink, who edits short stories for a magazine, explained that she thinks of Astraea as a long short story. She wrote it especially for this prize, within two months and for Ali Smith, as it were (she mentioned how formative How to Be Both was for her as a writer). Due to time and word limit constraints, she deliberately crafted a small character arc and didn’t do loads of research, though she had been looking into ships’ surgeons’ journals at the time. She has Irish convict ancestry but noted that this is not uncommon in Tasmania. Astraea is a “sneaky prequel” to her first novel, which has been published in Australia.

Deborah Tomkins

Aerth was originally titled First, Do No Harm, which had the potential to confuse those looking for a medical read. Aerth and Urth are different planets with parallels to our own. The novella tells the story of Magnus, an Everyman on a deeply forested planet heading into an Ice Age. Tomkins first wrote it for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted, then added to it. She initially sent the book to sci-fi publishers but was told it was not ‘sci-fi enough’.

Griffiths remarked that the shortlist was all-female and that the two winners show how a novella can do many different things: Astraea is at the low end of the word count at 22,000 words and takes place over just 36 hours; Aerth is towards the upper limit at 36,000 words and spans about 40 years.

Neil Griffiths

All the panellists dismissed the idea of a hierarchy with the full-length novel at the top. Griffiths said that the constraints of the novella, to need to discard and discard, make it stand out.

A further title from the 2024 shortlist, We Hexed the Moon by Mollyhall Seeley, will also be published by Weatherglass next year, and submissions are now open for the Weatherglass Novella Prize 2025.

Many thanks for my free ticket to a great event. Weatherglass has also kindly offered to send Cathy and me copies of the two novellas to review over the course of #NovNov. I’m looking forward to reading both winners!

Summery Reading, Part I: Heatwave, Summer Fridays

Here we are between short, bearable heat waves. As the climate changes, I’m more grateful than ever to live somewhere with reasonably mild and predictable weather; I don’t miss the swampy humidity of the Maryland summers I grew up with one bit. Today I have some brief thoughts on a first pair of summer-themed reads I picked up last month: a queasy coming-of-age novella about French teenagers’ self-destructive actions on a camping holiday; and a fun, nostalgic romance novel set in New York City at the turn of the millennium.

Heatwave by Victor Jestin (2019; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Sam Taylor]

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

The rest of the book takes place over about 24 hours, the final day of a two-week vacation. Leo stumbles about as if in a trance, outwardly relating to his family, a male friend who seems to have a crush on him, and girls he’d like to sleep with, but all the while inwardly wondering what to do next. “I hadn’t made many stupid mistakes in my seventeen years of life. This one was difficult to understand. It all happened too fast; I felt powerless.” This is interesting enough if you like unreliable teenage narrators or are drawn by the critics’ comparisons to Françoise Sagan – accurate for the sense of sleepwalking toward disaster. One could easily breeze through the 104 pages during one hot afternoon. It didn’t stand out to me particularly, though. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell (2024)

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

It’s overlong and reasonably predictable, but I enjoyed the languid unfolding of the romance over the weeks of summer 1999. It was truly a simpler time when you had to dial up and wait for an inbox to load instead of having it in your pocket 24/7. Every Friday afternoon, Sawyer and Nick do touristy things like taste-test hotdogs and slushees, ride the Staten Island ferry back and forth all day, and visit little-known bars and restaurants Nick knows through his amateur rock band. They try to convince themselves that these are not dates. It’s like time outside of time for them, and a chance to sightsee in one’s own town. Eventually, though, Sawyer has to face reality. The 2001 framing story reflects the fact that, after the events of 9/11, many asked themselves what they really wanted out of life. This was cute but doesn’t quite live up to, e.g., Romantic Comedy. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Any “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again. At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.  Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.

Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.  February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,