#ReadIndies Review Catch-Up: Chevillard, Hopkins & Bateman, McGrath, Richardson

Quick thoughts on some more review catch-up books, most of them from 2025. It’s a miscellaneous selection today: absurdist flash fiction by a prolific French author, a self-help graphic novel about surviving heartbreak, a blend of bird photography and poetry, and a debut poetry collection about life and death as encountered by a parish priest.

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard (2024)

[Trans. from French by David Levin Becker]

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

With thanks to the University of Yale Press for the free copy for review.

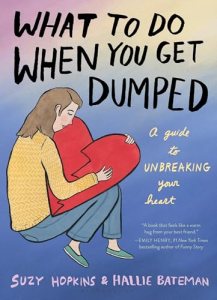

What to Do When You Get Dumped: A Guide to Unbreaking Your Heart by Suzy Hopkins; illus. Hallie Bateman (2025)

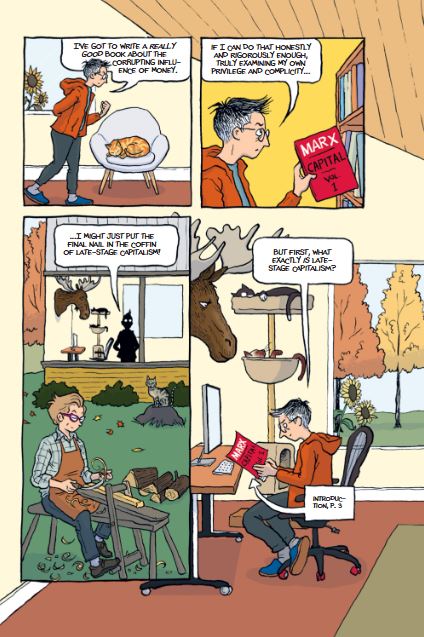

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free e-copy for review.

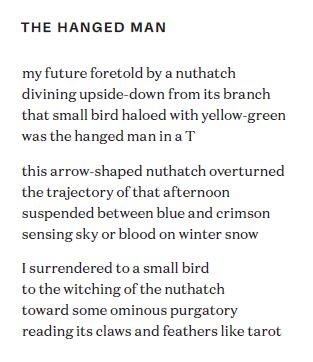

The Beauty of Vultures by Wendy McGrath; photos by Danny Miles (2025)

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

Other poems describe birds, address them directly, or take on their perspectives. Birds are a reassuring presence (cf. Ted Hughes on swifts): “I counted on our robins to return every spring” as a balm, the anxious speaker reports in “Air raid siren.” A nest of gape-mouthed baby swallows in an outhouse is the prize at the end of a long countryside walk. With its alliteration and repetition, “The Goldfinch Charm” feels like an incantation. Birds model grace (or at least the appearance of grace):

Assume a buoyancy, lightness, as though you were about to fly.

That yellow rubber duck is my surreal mythology.

Head above water. Stay calm. Paddle like crazy.

They link the natural world and the human in these gorgeous poems that interact with the images in ways that both lead and illuminate.

A female swan is a pen and eyes open

I try to write this dream:

a moment stolen or given.

Published by NeWest Press. With thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review.

Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson (2026)

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

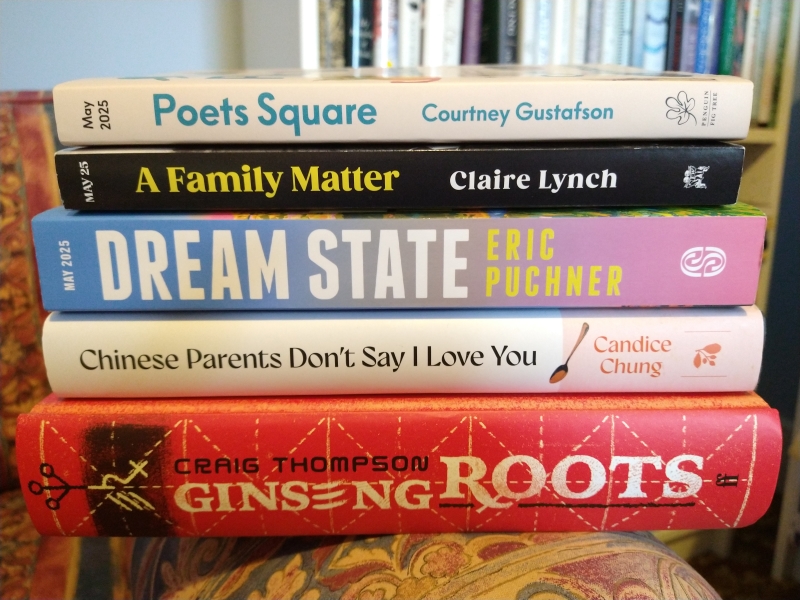

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

Last Love Your Library of 2025 & Another for #DoorstoppersInDecember

Thanks to Eleanor, Margaret and Skai for writing about their recent library reading! Marcie also joined in with a post about completing Toronto Public Library’s 2025 Reading Challenge with books by Indigenous authors.

I managed to fit in a few more 2025 releases before Christmas. My plan for January is to focus on reading from my own shelves (which includes McKitterick Prize submissions and perhaps also review copies to catch up on), so expect next month to be a lighter one.

My recent reading has featured many mentions of how much libraries mean, particularly to young women.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

My library use over the last month:

(links are to any reviews of books not already covered on the blog)

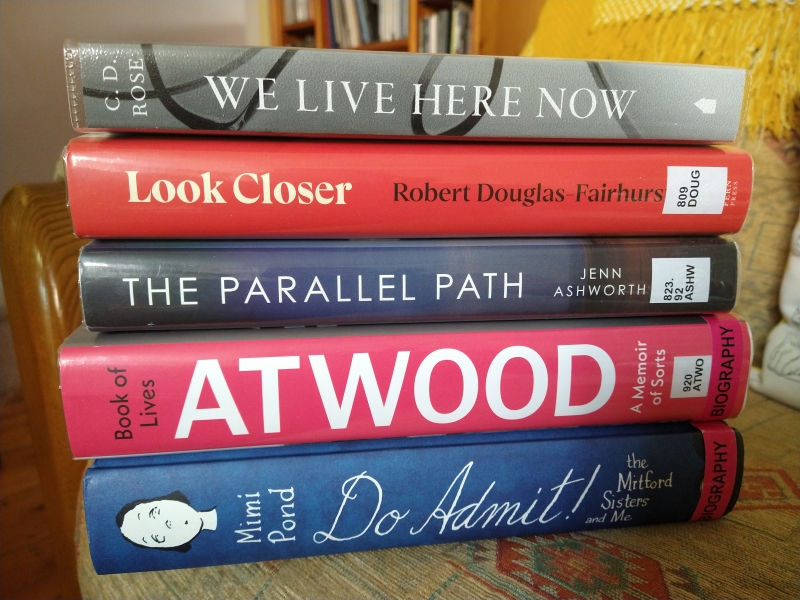

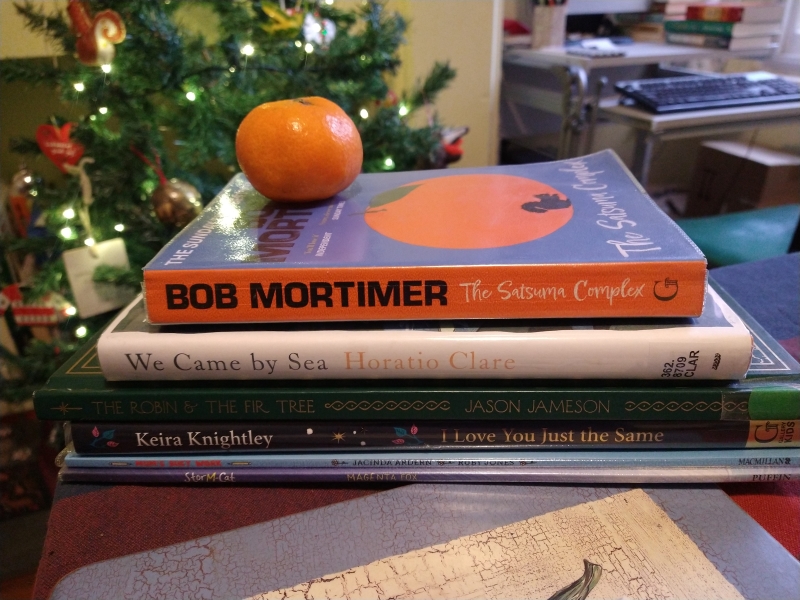

READ

- Mum’s Busy Work by Jacinda Ardern; illus. Ruby Jones

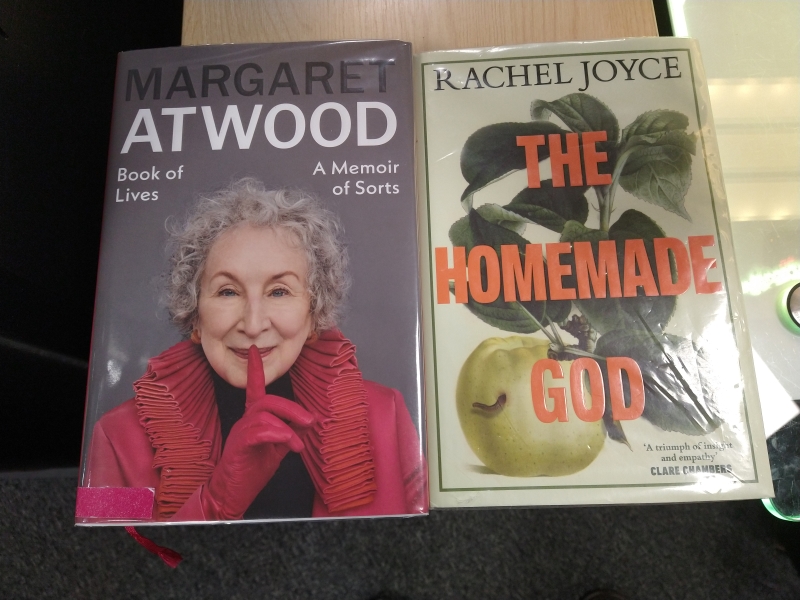

- Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

- Storm-Cat by Magenta Fox

- The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson

- I Love You Just the Same by Keira Knightley – Proof that celebrities should not be writing children’s books. I would say the story and drawings were pretty good … if she were a college student.

- Winter by Val McDermid

- The Search for the Giant Arctic Jellyfish, The Search for Carmella, & The Search for Our Cosmic Neighbours by Chloe Savage

- Weirdo Goes Wild by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird; illustrated by Magenta Fox

- Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

+ A final contribution to #DoorstoppersInDecember

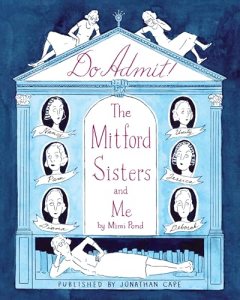

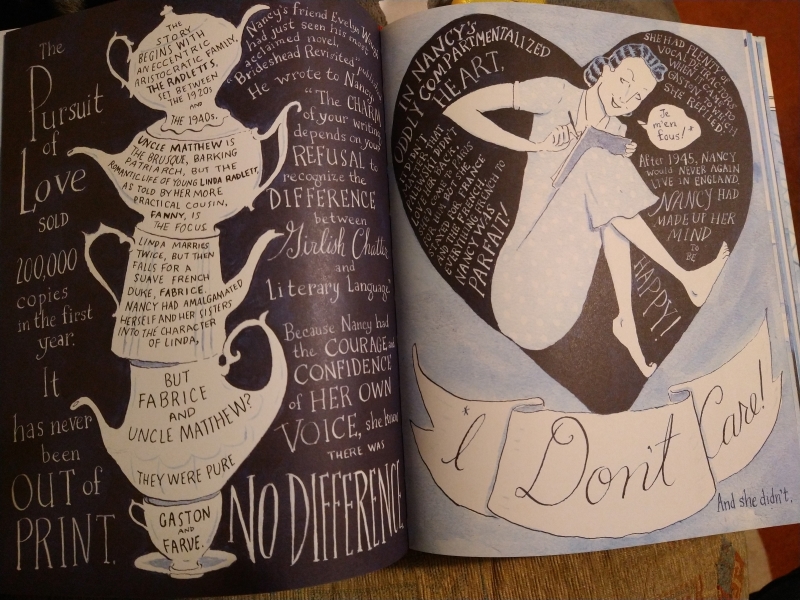

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me by Mimi Pond

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages]

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages] ![]()

CURRENTLY READING

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- The Satsuma Complex by Bob Mortimer (for book club in January; I’m grumpy about it because I didn’t vote for this one, had no idea who the author [a TV comedian in the UK] was, and the writing is shaky at best)

- We Live Here Now by C.D. Rose

SKIMMED

- Look Closer: How to Get More out of Reading by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

- We Came by Sea by Horatio Clare

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith

- Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- Ultra-Processed People by Dr. Chris van Tulleken (for book club in February)

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

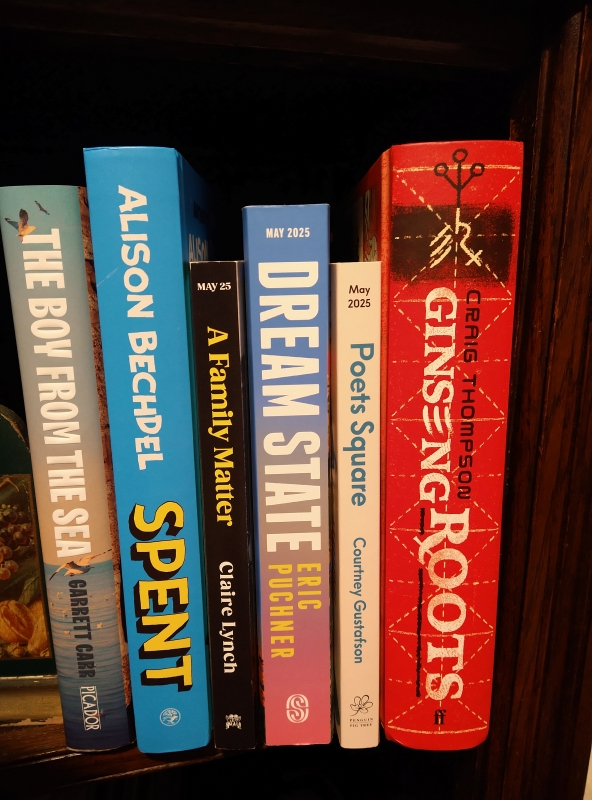

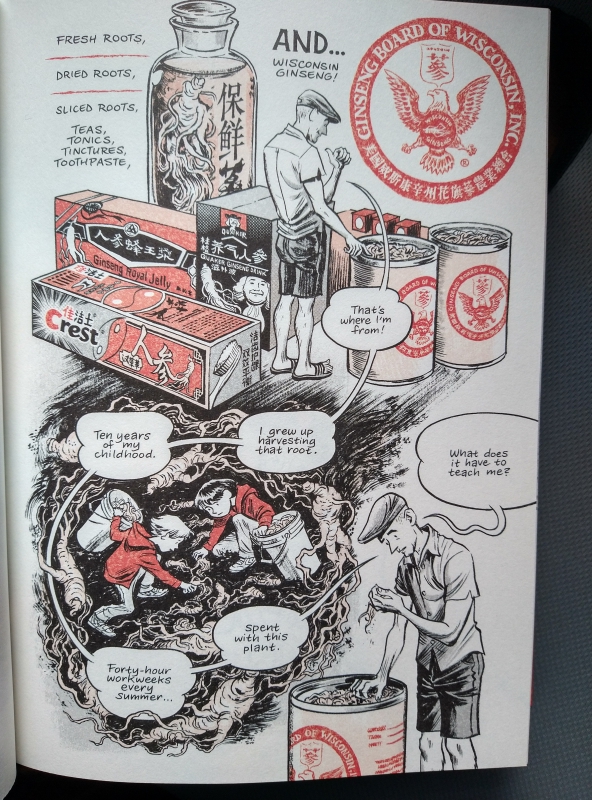

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research. The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint.

The author was the granddaughter of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World et al.). While her father was away in India, she was shunted between two homes: Grandmother and Grandfather Freeman’s Sussex estate, and the mausoleum-cum-gallery her paternal grandmother, “Grand,” maintained in Kensington. The grandparents have very different ideas about the sorts of foodstuffs and activities that are suitable for little girls. Both households have servants, but Grand only has the one helper, Helen. Grand probably has a lot of money tied up in property and paintings but lives like a penniless widow. Grand encourages abstemious habits – “Don’t be ruled by Brother Ass, he’s only your body and a nuisance” – and believes in boiled milk and margarine. The single egg she has Helen serve Diana in the morning often smells off. “Food is only important as fuel; whether we like it or not is quite immaterial,” Grand insists. Diana might more naturally gravitate to the pleasures of the Freeman residence, but when it comes time to give a tour of the Holman Hunt oeuvre, she does so with pride. There are some funny moments, such as Diana asking where babies come from after one of the Freemans’ maids gives birth, but this felt so exaggerated and fictionalized – how could she possibly remember details and conversations at the distance of several decades? – that I lost interest by the midpoint. Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride.

Some methods of transport are just more romantic than others. The editors’ introduction notes that “Trains were by far the most popular … followed by aeroplanes and then boats.” Walks and car journeys were surprisingly scarce, they observed, though there are a couple of poems about wandering in New York City. Often, the language is of maps, airports, passports and long flights; of trading one place for another as exile, expatriate or returnee. The collection circuits the globe: China, the Middle East, Greece, Scandinavia, the bayous of the American South. France and Berlin show up more than once. The Emma Press anthologies vary and this one had fewer standout entries than average. However, a few favourites were Nancy Campbell’s “Reading the Water,” about a boy launching out to sea in a kayak; Simon Williams’s “Aboard the Grey Ghost,” about watching for dolphins on a wartime voyage from England to the USA; and Vicky Sparrow’s “Dual Gauge,” which follows a train of thought – about humans as objects moving, perhaps towards death – during a train ride. As I found when I

As I found when I  I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

I’d never encountered “chapbook” being used for prose rather than poetry, but it’s an apt term for this 61-page paperback containing 18 stories. It’s remarkable how much King can pack into just a few pages: a voice, a character, a setting and situation, an incident, a salient backstory, and some kind of epiphany or resolution. Fifteen of the pieces focus on one named character, with another three featuring a set (“Ladies,” hence the title). Laura-Jean wonders whether it was a mistake to tell her ex’s mother what she really thinks about him in a Christmas card. A love of ice cream connects Margot’s past and present. A painting in a museum convinces Paige to reconnect with her estranged sister. Alice is sure she sees her double wandering around, and Mary contemplates stealing other people’s cats. The women are moved by rage or lust; stymied by loneliness or nostalgia. Is salvation to be found in scripture or poetry? Each story is distinctive, with no words wasted. I’ll look out for future work by King.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

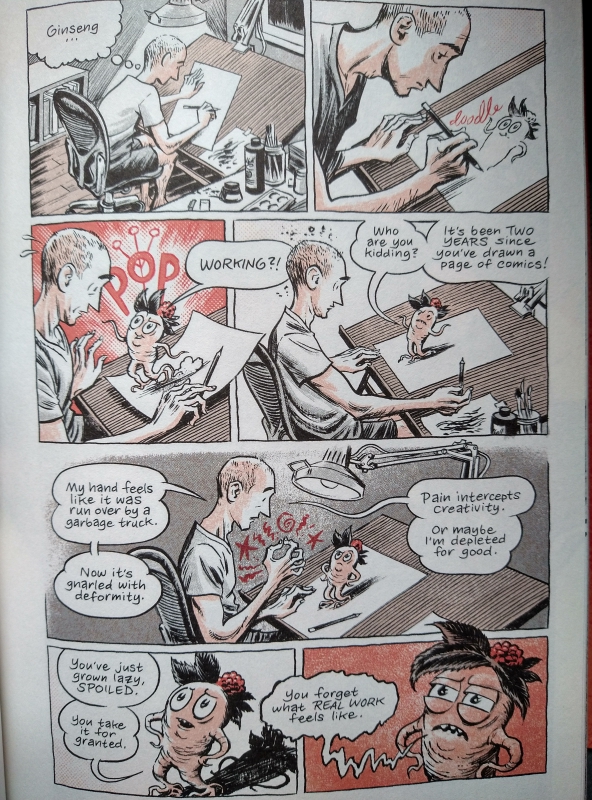

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

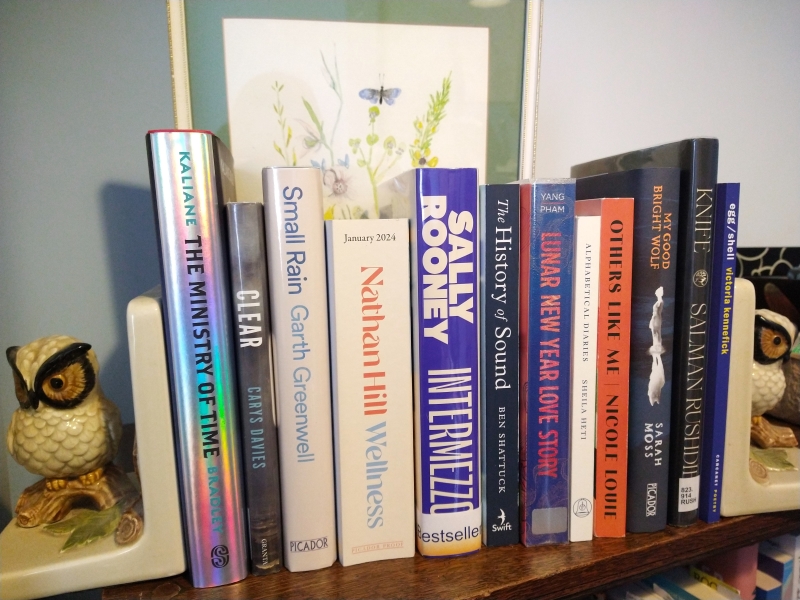

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.