Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

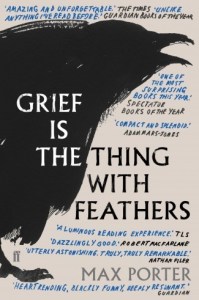

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

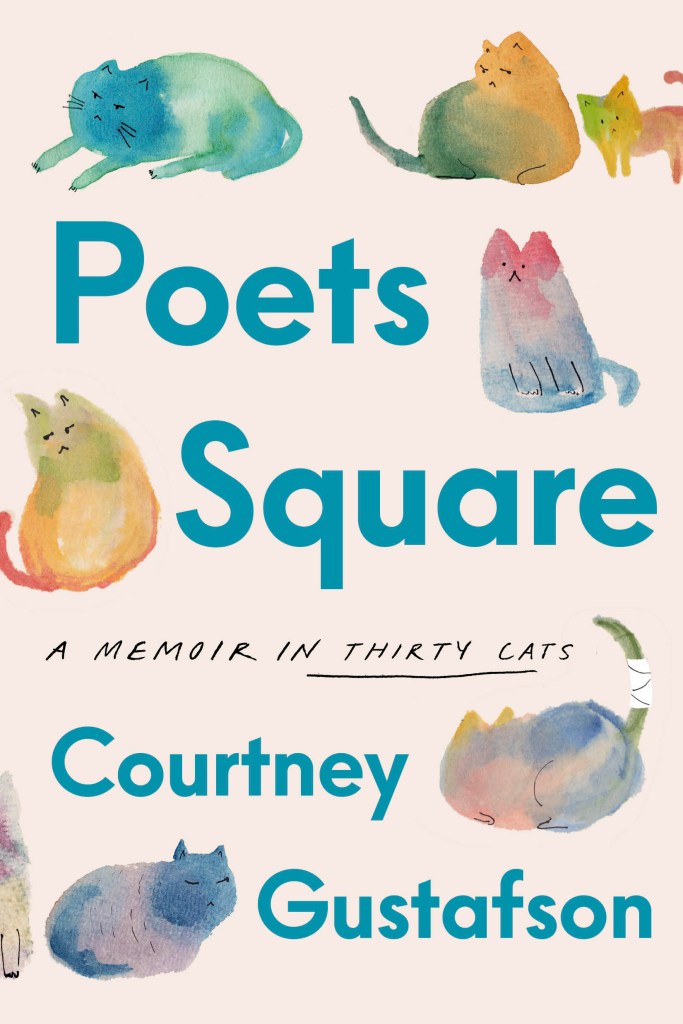

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

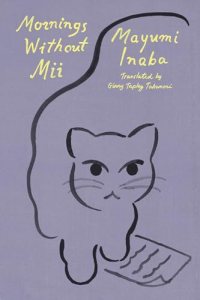

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Book Serendipity, Mid-February to Mid-April

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

Last time, my biggest set of coincidences was around books set in or about Korea or by Korean authors; this time it was Ghana and Ghanaian authors:

- Reading two books set in Ghana at the same time: Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor and His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie. I had also read a third book set in Ghana, What Napoleon Could Not Do by DK Nnuro, early in the year and then found its title phrase (i.e., “you have done what Napoleon could not do,” an expression of praise) quoted in the Medie! It must be a popular saying there.

- Reading two books by young Ghanaian British authors at the same time: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley and Maame by Jessica George.

And the rest:

- An overweight male character with gout in Where the God of Love Hangs Out by Amy Bloom and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho by Paterson Joseph.

- I’d never heard of “shoegaze music” before I saw it in Michelle Zauner’s bio at the back of Crying in H Mart, but then I also saw it mentioned in Pulling the Chariot of the Sun by Shane McCrae.

- Sheila Heti’s writing on motherhood is quoted in Without Children by Peggy O’Donnell Heffington and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata. Before long I got back into her novel Pure Colour. A quote from another of her books (How Should a Person Be?) is one of the epigraphs to Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home.

- Reading two Mexican books about motherhood at the same time: Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata.

- Two coming-of-age novels set on the cusp of war in 1939: The Inner Circle by T.C. Boyle and Martha Quest by Doris Lessing.

- A scene of looking at peculiar human behaviour and imagining how David Attenborough would narrate it in a documentary in Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson and I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai.

- The painter Caravaggio is mentioned in a novel (The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent) plus two poetry books (The Fourth Sister by Laura Scott and Manorism by Yomi Sode) I was reading at the same time.

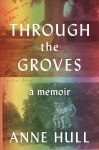

- Characters are plagued by mosquitoes in The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

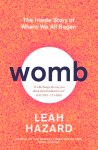

- Edinburgh’s history of grave robbing is mentioned in The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent and Womb by Leah Hazard.

- I read a chapter about mayflies in Lev Parikian’s book Taking Flight and then a poem about mayflies later the same day in Ephemeron by Fiona Benson.

- Childhood reminiscences about playing the board game Operation and wetting the bed appear in Homesick by Jennifer Croft and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

- Fiddler on the Roof songs are mentioned in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman.

- There’s a minor character named Frith in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

- Scenes of a female couple snogging in a bar bathroom in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and The Garnett Girls by Georgina Moore.

- The main character regrets not spending more time with her father before his sudden death in Maame by Jessica George and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti.

- The main character is called Mira in Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti, and a Mira is briefly mentioned in one of the stories in Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans.

- Macbeth references in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – my second Macbeth-sourced title in recent times, after Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin last year.

- A ‘Goldilocks scenario’ is referred to in Womb by Leah Hazard (the ideal contraction strength) and Taking Flight by Lev Parikian (the ideal body weight for a bird).

- Caribbean patois and mention of an ackee tree in the short story collection If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery and the poetry collection Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa.

- The Japanese folktale “The Boy Who Drew Cats” appeared in Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng, which I read last year, and then also in Enchantment by Katherine May.

- Chinese characters are mentioned to have taken part in the Tiananmen Square massacre/June 4th incident in Dear Chrysanthemums by Fiona Sze-Lorrain and Oh My Mother! by Connie Wang.

- Endometriosis comes up in What My Bones Know by Stephanie Foo and Womb by Leah Hazard.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

First Encounter: Haruki Murakami (The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle)

I don’t know why I resisted reading Haruki Murakami for so long. I have some friends who are big fans of his work, but I always thought his fiction would be a bit too odd for me. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994), which I just finished last night, is certainly bizarre, but in the best possible way: it questions our comfort in the everyday by contorting familiar elements in the way that dreams do. This is the story of a young man who’s become lost in his own life and is looking for the way back. It’s a hero’s quest through a baffling, mystical underworld.

It all starts with a missing cat and a dirty phone call. It’s 1984. Thirty-year-old Toru Okada recently left his job as a law clerk and has been aimlessly spending days at home while his wife, Kumiko, goes out to her magazine editor job. A week ago the cat – named Noboru Wataya, after Toru’s hateful brother-in-law – disappeared, so he’s cooking himself some spaghetti and pondering his cat hunting strategy when he gets a call from what seems to be a phone sex hotline, except that the female speaker claims to know him well. And unexpected phone calls just keep coming, including from Malta Kano, a clairvoyant who foretells that he will experience “Bad things that seem good at first, and good things that seem bad at first.”

The cover on my library paperback. Yuck!

There’s a narrow alleyway behind their suburban Tokyo house that cuts between two rows of back gardens. On these hot June days, it’s an almost preternaturally still place, with the quiet broken only by the mechanical-sounding call of a creature Toru thinks of as the wind-up bird. He heads down the alley to look for the cat, but all he finds is the deserted (haunted?) Miyawaki house with a bird sculpture and an old, dry well in its yard. He also meets May Kasahara, a blunt sixteen-year-old who’s taking a year off school after a motorcycle accident.

So far, so realist (mostly). But things keep getting weirder, mainly through a series of further appearances and disappearances. The first to go is Kumiko, who says she’s been having an affair. Toru doesn’t believe, her, though. Or, rather, he doesn’t think a pattern of cheating is enough of an explanation for her leaving everything behind one morning. He knows there’s a deeper force driving this, and he’s determined to rescue his wife from it. Meanwhile, he has more encounters with and stories of pain from peculiar characters – everyone from a World War II lieutenant and a former fashion designer to Malta Kano’s ex-prostitute sister, Creta.

Rather like a Kafka antihero, Toru simply can’t grasp what’s happening to him.

I shook my head. Too many things were being left unexplained. The one thing I understood for sure was that I didn’t understand a thing. … “I’m sick of riddles. I need something concrete that I can get my hands on. Hard facts. Something I can use as a lever to pry the door open. That’s what I want.”

Yet his first-person narration anchors the book, making him an Everyman who we journey along with in his state of confusion. So even as the plot gets increasingly outlandish and somewhat taken over by other voices – via long monologues, letters, or tales stored in computer files – we always have this sympathetic protagonist to come home to. Like in Dickens’s novels, I noticed that minor characters like the Kano sisters keep turning up just when you’re in danger of forgetting them due to the weight of the intervening pages.

I prefer this, or pretty much any other, cover.

Yesterday I gave a gleeful squeal when a review copy of just 190 pages arrived. “So you love short books?” my husband asked. I do … but I also adore long ones that have a darn good reason to be that long – creating a whole world you can get lost in. That’s what I’m trying to celebrate with this year’s monthly Doorstopper series: books whose 500+ pages fly by, best consumed in big gulps. Such won’t always be the case: City on Fire and Hame both felt like a slog in places, though were ultimately worth engaging with. But my first encounter with Murakami showcased expansive storytelling at its best. I want to read more books like this.

I’m not entirely sure I comprehended all that happens at the end of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, but that doesn’t really matter. The novel left me mesmerized, shaking my head as if waking up from the strangest dream but hoping to someday go back to its world. And for 99.8% of it I forgot that I was reading a work in translation.

If I were to make a word cloud of important phrases from the book, it would look off the wall: lemon drops, a necktie, wells, bald men, baseball bats, birthmarks, being skinned alive, zoo animals, a hotel room, a wig factory, and so on. That list might intrigue you; equally, it might put you off in the same way that I was always daunted by the idea of Japanese magic realism. Let me assure you, this stunning novel is so much more than the sum of its parts.

My rating:

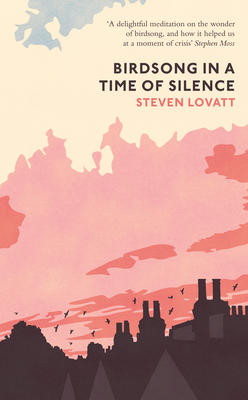

During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, from Birmingham and now based in South Wales, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. (He even gives step-by-step instructions for sounding like a magpie.) Birdsong takes him back to childhood, but feels deeper than that: a cultural memory that enters into our poetry and will be lost forever if we allow our declining bird species to continue on the same trajectory.

During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, from Birmingham and now based in South Wales, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. (He even gives step-by-step instructions for sounding like a magpie.) Birdsong takes him back to childhood, but feels deeper than that: a cultural memory that enters into our poetry and will be lost forever if we allow our declining bird species to continue on the same trajectory.

Lovatt must have been a pupil of Moss’s on the Bath Spa University MA degree in Travel and Nature Writing. The prolific Moss’s latest also reflects on the spring of 2020, but in a more overt diary format. Devoting one chapter to each of the 13 weeks of the first lockdown, he traces the season’s development alongside his family’s experiences and the national news. With four of his children at home, along with one of their partners and a convalescing friend, it’s a pleasingly full house. There are daily cycles or walks around “the loop,” a three-mile circuit from their front door, often with Rosie the Labrador; there are also jaunts to corners of the nearby Avalon Marshes. Nature also comes to him, with songbirds in the garden hedges and various birds of prey flying over during their 11:00 coffee breaks.

Lovatt must have been a pupil of Moss’s on the Bath Spa University MA degree in Travel and Nature Writing. The prolific Moss’s latest also reflects on the spring of 2020, but in a more overt diary format. Devoting one chapter to each of the 13 weeks of the first lockdown, he traces the season’s development alongside his family’s experiences and the national news. With four of his children at home, along with one of their partners and a convalescing friend, it’s a pleasingly full house. There are daily cycles or walks around “the loop,” a three-mile circuit from their front door, often with Rosie the Labrador; there are also jaunts to corners of the nearby Avalon Marshes. Nature also comes to him, with songbirds in the garden hedges and various birds of prey flying over during their 11:00 coffee breaks.

For Halle, who worked in the State Department, nature was an antidote to hours spent shuffling papers behind a desk. In this spring of 1945, there was plenty of wildfowl to see in central D.C. itself, but he also took long early morning bike rides along the Potomac or the C&O Canal, or in Rock Creek Park. From first migrant in February to last in June, he traces the spring mostly through the birds that he sees. More so than the specific observations of familiar places, though, I valued the philosophical outlook that makes Halle a forerunner of writers like Barry Lopez and Peter Matthiessen. He notes that those caught up in the rat race adapt the world to their comfort and convenience, prizing technology and manmade tidiness over natural wonders. By contrast, he feels he sees more clearly – literally as well as metaphorically – when he takes the long view of a landscape.

For Halle, who worked in the State Department, nature was an antidote to hours spent shuffling papers behind a desk. In this spring of 1945, there was plenty of wildfowl to see in central D.C. itself, but he also took long early morning bike rides along the Potomac or the C&O Canal, or in Rock Creek Park. From first migrant in February to last in June, he traces the spring mostly through the birds that he sees. More so than the specific observations of familiar places, though, I valued the philosophical outlook that makes Halle a forerunner of writers like Barry Lopez and Peter Matthiessen. He notes that those caught up in the rat race adapt the world to their comfort and convenience, prizing technology and manmade tidiness over natural wonders. By contrast, he feels he sees more clearly – literally as well as metaphorically – when he takes the long view of a landscape. I marked so many passages of beautiful description. Halle had mastered the art of noticing. But he also sounds a premonitory note, one that was ahead of its time in the 1940s and needs heeding now more than ever: “When I see men able to pass by such a shining and miraculous thing as this Cape May warbler, the very distillate of life, and then marvel at the internal-combustion engine, I think we had all better make ourselves ready for another Flood.”

I marked so many passages of beautiful description. Halle had mastered the art of noticing. But he also sounds a premonitory note, one that was ahead of its time in the 1940s and needs heeding now more than ever: “When I see men able to pass by such a shining and miraculous thing as this Cape May warbler, the very distillate of life, and then marvel at the internal-combustion engine, I think we had all better make ourselves ready for another Flood.”

More cherry blossoms over tourist landmarks! This is part of a children’s series inspired by the 1805 English rhyme about London; other volumes visit New York City, Paris, and Rome. In rhyming couplets, he takes us from the White House to the Lincoln Memorial via all the other key sights of the Mall and further afield: museums and monuments, the Library of Congress, the National Cathedral, Arlington Cemetery, even somewhere I’ve never been – Theodore Roosevelt Island. Realism and whimsy (a kid-sized cat) together; lots of diversity in the crowd scenes. What’s not to like? (Titled Kitty cat, kitty cat… in the USA.)

More cherry blossoms over tourist landmarks! This is part of a children’s series inspired by the 1805 English rhyme about London; other volumes visit New York City, Paris, and Rome. In rhyming couplets, he takes us from the White House to the Lincoln Memorial via all the other key sights of the Mall and further afield: museums and monuments, the Library of Congress, the National Cathedral, Arlington Cemetery, even somewhere I’ve never been – Theodore Roosevelt Island. Realism and whimsy (a kid-sized cat) together; lots of diversity in the crowd scenes. What’s not to like? (Titled Kitty cat, kitty cat… in the USA.)  Like a Murakami protagonist, Taro is a divorced man in his thirties, mildly interested in the sometimes peculiar goings-on in his vicinity. Rumor has it that his Tokyo apartment complex will be torn down soon, but for now the PR manager is happy enough here. “Avoiding bother was Taro’s governing principle.” But bother comes to find him in the form of a neighbor, Nishi, who is obsessed with a nearby house that was the backdrop for the art book Spring Garden, a collection of photographs of a married couple’s life. Her enthusiasm gradually draws Taro into the depicted existence of the TV commercial director and actress who lived there 25 years ago, as well as the young family who live there now. This Akutagawa Prize winner failed to hold my interest – like

Like a Murakami protagonist, Taro is a divorced man in his thirties, mildly interested in the sometimes peculiar goings-on in his vicinity. Rumor has it that his Tokyo apartment complex will be torn down soon, but for now the PR manager is happy enough here. “Avoiding bother was Taro’s governing principle.” But bother comes to find him in the form of a neighbor, Nishi, who is obsessed with a nearby house that was the backdrop for the art book Spring Garden, a collection of photographs of a married couple’s life. Her enthusiasm gradually draws Taro into the depicted existence of the TV commercial director and actress who lived there 25 years ago, as well as the young family who live there now. This Akutagawa Prize winner failed to hold my interest – like

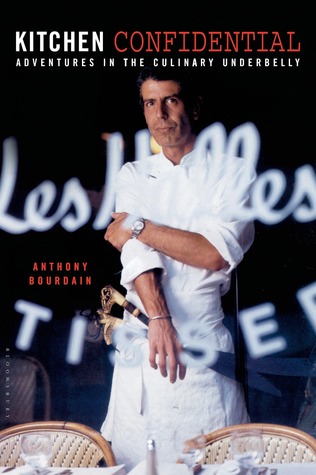

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture. (20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast. (20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.

(20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right. I was utterly entranced by my first two Haruki Murakami novels,

I was utterly entranced by my first two Haruki Murakami novels,  As the narrator makes his way to The Rat’s mountain hideaway, an hour and a half from the nearest town, he’s moving further from rational explanations and deeper into solitude and communion with ghosts. There’s some trademark Murakami strangeness, but the book is too short to give free rein to the magic realist plot, and I felt like there were too many loose ends after his return from The Rat’s, especially around his girlfriend’s disappearance.

As the narrator makes his way to The Rat’s mountain hideaway, an hour and a half from the nearest town, he’s moving further from rational explanations and deeper into solitude and communion with ghosts. There’s some trademark Murakami strangeness, but the book is too short to give free rein to the magic realist plot, and I felt like there were too many loose ends after his return from The Rat’s, especially around his girlfriend’s disappearance.

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?”

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?” It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author.

It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author. The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of

The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of