Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

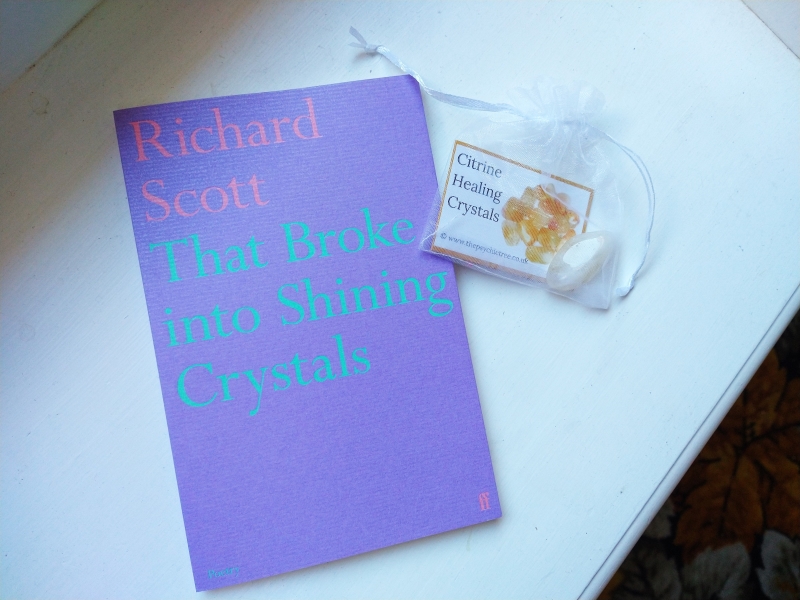

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

20 Books of Summer, 11–13: Campbell, Julavits, Lu

Two solid servings of women’s life writing plus a novel about a Chinese woman stuck in roles she’s not sure she wants anymore.

Thunderstone: A true story of losing one home and discovering another by Nancy Campbell (2022)

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

The title refers to a fossil that has been considered a talisman in various cultures, and she needed the good luck during a period that involved accidental carbon monoxide poisoning and surgery for an ovarian abnormality (but it didn’t protect her books, which were all destroyed in a leaking shipping container – the horror!). I most enjoyed the longer entries where she muses on “All the potential lives I moved on from” during 20 years in Oxford and elsewhere, which makes me think that I would have preferred a more traditional memoir by her. Covid narratives feel really dated now, unfortunately. (New (bargain) purchase from Hungerford Bookshop with birthday voucher)

Directions to Myself: A Memoir by Heidi Julavits (2023)

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Mostly the memoir takes readers through everyday conversations the author has with friends and family about situations of inequality or harassment. Through her words she tries to gently steer her son towards more open-minded ideas about gender roles. She also entrances him and his sleepover friends with a real-life horror story about being chased through the French countryside by a man in a car. The tenor of her musings appealed to me, but already the details are fading. I suspect this will mean much more to a parent.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu (2023)

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy.

Reading about Mothers and Motherhood: Cosslett, Cusk, Emma Press Poetry, Heti, and Pachico

It was (North American) Mother’s Day at the weekend, an occasion I have complicated feelings about now that my mother is gone. But I don’t think I’ll ever stop reading and writing about mothering. At first I planned to divide my recent topical reads (one a reread) into two sets, one for ambivalence about becoming a mother and the other for mixed feelings about one’s mother. But the two are intertwined – especially in the poetry anthology I consider below – such that they feel more like facets of the same experience. I also review two memoirs (one classic; one not so much) and two novels (autofiction vs. science fiction).

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett (2023)

This was on my Most Anticipated list last year. A Covid memoir that features adopting a cat and agonizing over the question of whether to have a baby sounded right up my street. And in the earlier pages, in which Cosslett brings Mackerel the kitten home during the first lockdown and interrogates the stereotype of the crazy cat lady from the days of witches’ familiars onwards, it indeed seemed to be so. But the further I got, the more my pace through the book slowed to a limp; it took me 10 months to read, in fits and starts.

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

3) Cosslett claims to reject clichéd notions about pets being substitutes for children, then goes right along with them by presenting Mackerel as an object of mothering (“there is something about looking after her that has prodded the carer in me awake”) and setting up a parallel between her decision to adopt the kitten and her decision to have a child. “Though I had all these very valid reasons not to get a cat, I still wanted one,” she writes early on. And towards the end, even after she’s considered all the ‘very valid reasons’ not to have a baby, she does anyway. “I need to find another way of framing it, if I am to do it,” she says. So she decides that it’s an expression of bravery, proof of overcoming trauma. I was unconvinced. When people accuse memoirists of being navel-gazing, this is just the sort of book they have in mind. I wonder if those familiar with her Guardian journalism would agree. (Public library)

A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother by Rachel Cusk (2001)

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

I understand that crying, being the baby’s only means of communication, has any number of causes, which it falls to me, as her chief companion and link to the world, to interpret.

Have you taken her to toddler group, the health visitor enquired. I had not. Like vaccinations and mother and baby clinics, the notion instilled in me a deep administrative terror.

We [new parents] are heroic and cruel, authoritative and then servile, cleaving to our guesses and inspirations and bizarre rituals in the absence of any real understanding of what we are doing or how it should properly be done.

She approaches mumsy things as an outsider, clinging to intellectualism even though it doesn’t seem to apply to this new world of bodily obligation, “the rambling dream of feeding and crying that my life has become.” By the end of the book, she does express love for and attachment to her daughter, built up over time and through constant presence. But she doesn’t downplay how difficult it was. “For the first year of her life work and love were bound together, fiercely, painfully.” This is a classic of motherhood literature, and more engaging than anything else I’ve read by Cusk. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

There’s a great variety of subject matter and tone here, despite the apparently narrow theme. There are poems about pregnancy (“I have a comfort house inside my body” by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi), childbirth (“The Tempest” by Melinda Kallismae) and new motherhood, but also pieces imagining the babies that never were (“Daughters” by Catherine Smith) or revealing the complicated feelings adults have towards their mothers.

“All My Mad Mothers” by Jacqueline Saphra depicts a difficult bond through absurdist metaphors: “My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her in a bath / of olive oil, or was it sesame, her skin well-slicked / … / to ease her way into this world. Or out of it.” I also loved her evocation of a mother–daughter relationship through a rundown of a cabinet’s contents in “My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

I connected with these perhaps more so than the poems about becoming a mother, but there are lots of strong entries and very few unmemorable ones. Even within the mothers’ testimonials, there is ambivalence: the visceral vocabulary in “Collage” by Anna Kisby is rather morbid, partway to gruesome: “You look at me // like liver looks at me, like heart. You are familiar as innards. / In strip-light I clean your first shit. I’m not sure I do it right. / It sticks to me like funeral silk. … There is a window // guillotined into the wall. I scoop you up like a clod.”

A favourite pair: “Talisman” by Anna Kirk and “Grasshopper Warbler” by Liz Berry, on facing pages, for their nature imagery. “Child, you are grape / skins stretched over fishbones. … You are crab claws unfurling into cabbage leaves,” Kirk writes. Berry likens pregnancy to patient waiting for an elusive bird by a reedbed. (Free copy – newsletter giveaway)

Motherhood by Sheila Heti (2018)

I first read this nearly six years ago (see my original review), when I was 34; I’m now 40 and pretty much decided against having children, but FOMO is a lingering niggle. Even though I already owned it in hardback, I couldn’t resist picking up a nearly new paperback I saw going for 50 pence in a charity shop, if only for the Leanne Shapton cover – her simple, elegant watercolour style is instantly recognizable. Having a different copy also provided some novelty for my reread, which is ongoing; I’m about 80 pages from the end.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

For the past month or so, I’ve also been reading Alphabetical Diaries, so you could say that I’m pretty Heti-ed out right now, but I do so admire her for writing exactly what she wants to and sticking to no one else’s template. People probably react against Heti’s work as self-indulgent in the same way I did with Cosslett’s, but the former’s shtick works for me. (Secondhand purchase – Bas Books & Home, Newbury)

A few of the passages that have most struck me on this second reading:

I think that is how childbearing feels to me: a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.

I don’t want ‘not a mother’ to be part of who I am—for my identity to be the negative of someone else’s positive identity.

The whole world needs to be mothered. I don’t need to invent a brand new life to give the warming effect to my life I imagine mothering will bring.

I have to think, If I wanted a kid, I already would have had one by now—or at least I would have tried.

Jungle House by Julianne Pachico (2023)

{BEWARE SPOILERS}

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Mother is exacting but mercurial, strict about cleanliness yet apt to forget or overlook things during one of her “spells.” Lena pushes the boundaries of her independence, believing that Mother only wants to protect her but still longing to explore the degraded wilderness beyond the compound.

Mother was right, because Mother was always right about these kinds of things. The world was a complicated place, and Mother understood it much better than she did.

In the house, there was no privacy. In the house, Mother saw all.

Mother was Lena’s world. And Lena, in turn, was hers. No matter how angry they got at each other, no matter how much they fought, no matter the things that Mother did or didn’t do … they had each other.

It takes a while to work out just how tech-reliant this scenario is, what the repeated references to “the pit bull” are about, and how Lena emulated and resented Isabella, the Morel daughter, in equal measure. Even creepier than the satellites’ plan to digitize humans is the fact that Isabella’s security drone, Anton, can fabricate recorded memories. This reminded me a lot of Klara and the Sun. Tech themes aren’t my favourite, but I ultimately thought of this as an allegory of life with a narcissistic mother and the child’s essential task of breaking free. It’s not clinical and contrived, though; it’s a taut, subtle thriller with an evocative setting. (Public library)

See also: “Three on a Theme: Matrescence Memoirs”

Does one or more of these books take your fancy?

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

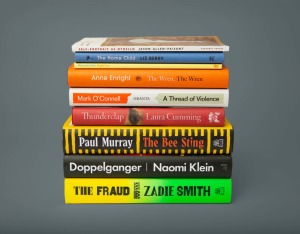

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

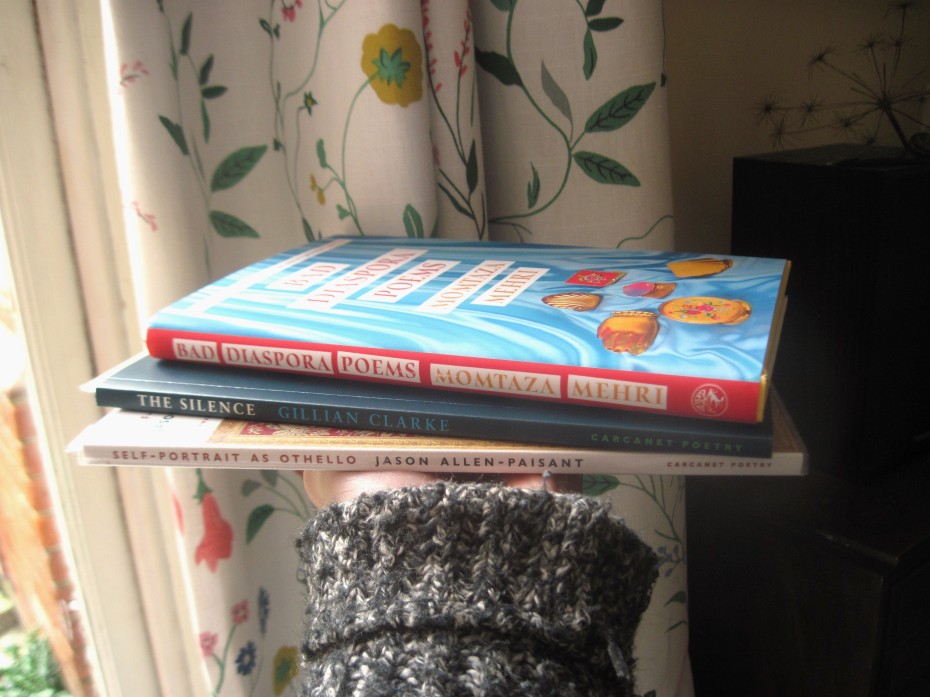

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend.

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend. This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in

This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in  The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Marsh is a retired brain surgeon and the author of

Marsh is a retired brain surgeon and the author of

On the face of it, he wasn’t an obvious candidate, not someone you would worry about. Yet there was family history: both of Patterson’s parents lost their fathers to suicide. And there was a bizarre direct connection between their two Kansas-based families: her maternal grandmother’s best friend became her paternal grandfather’s secretary and mistress.

On the face of it, he wasn’t an obvious candidate, not someone you would worry about. Yet there was family history: both of Patterson’s parents lost their fathers to suicide. And there was a bizarre direct connection between their two Kansas-based families: her maternal grandmother’s best friend became her paternal grandfather’s secretary and mistress.

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir