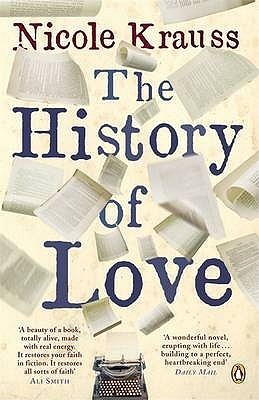

Adventures in Rereading: The History of Love by Nicole Krauss for Valentine’s Day

Special Valentine’s edition. Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet manage a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the ninth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024!

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library)

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Finishing my reread during a coffee date in Hungerford this morning.

My original rating (2011): ![]()

When I first read this, I mostly considered it in comparison to Krauss’s former husband Jonathan Safran Foer’s work. (I’ve long since read everything by both of them.) I noted then that it

has a lot of elements in common with Everything is Illuminated, such as a preoccupation with Eastern European and Jewish ancestry, quirky methods of narration including multiple voices, and a sweet humour that lies alongside such heart-rending stories of family and loss that tears are never far from your eyes. Leo Gursky and Alma Singer are delightful and distinct characters. I wasn’t sure about the missing/plagiarized/mistaken The History of Love itself; the ruined copies, the different translations, the way the manuscript was constantly changing hands – all this was intriguing, but the book itself was a postmodern jumble of magic realism and pointless meanderings of thought.

Dang, I was harsh! But admirably pithy about the plot. It’s intriguing that I’ve successfully reread Krauss but failed with Foer when I attempted Everything is Illuminated again in 2020. Reading the first, 9/11-set section of Confessions by Catherine Airey, I’ve also been recalling his Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and thinking it probably wouldn’t stand up to a reread either. I suspect I’d find it mawkish, especially with its child narrator. Alma evades that trap, perhaps by being that little bit older, though she sounds young because of how geeky and sheltered she is.

A May Sarton Birthday Celebration

These days I consider May Sarton one of my favourite authors, but I’ve only been reading her for about nine years, since I picked up Journal of a Solitude on a whim. (Ten years prior, when I was a senior in college working in a used bookstore on evenings and weekends, a customer came up and asked me if we had anything by May Sarton. I had never heard of her so said no, only later discovering that we shelved her in with Classic literature. Huh. I can only apologize to that long-ago customer for my ignorance and negligence.)

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

The two below, a journal and a novel, are works I’ve read more recently. Both were secondhand purchases, I think from Awesomebooks.com.

Encore: A Journal of the Eightieth Year (1993)

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Encore was the only journal I had left unread; soon it will be time to start rereading my top few. When Sarton wrote this in 1991–2, she was recovering from a spell of illness and assumed it would be her final journal. (In fact, At Eighty-Two would appear two years later.) Although she still struggles with pain and low energy, the overall tone is of gratitude and rediscovery of wonder. Whereas a few of the later journals can get a bit miserable because she’s so anxious about her health and the state of the world, here there is more looking back at life’s highlights. Perhaps because Margot Peters was in the process of researching her biography (which would not appear until after her death), she was nudged into the past more often. I especially appreciated a late entry where she lists “peak experiences,” ranging from her teen years to age 80. What a positive way of thinking about one’s life!

For many months I kept this as a bedside book and read just an entry or two a night. When I started reading it more quickly and straight through, I did note some repetition, which Sarton worried would result from her dictating into a recording device. But I don’t think this detracts significantly. In this volume, events of note include a trip to London and commemorative publications plus a conference all to mark her 80th birthday. She’s just as pleased with tiny signs of her success, though, such as a fan letter saying The House by the Sea inspired the reader to put up a bird feeder.

The Education of Harriet Hatfield (1988)

This is my eighth Sarton novel. In general, I’ve had less success with her fiction as it can be formulaic: characters exist to play stereotypical roles and/or serve as mouthpieces for the author’s opinions. That’s certainly true of Harriet Hatfield, who, like the protagonist of Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, is fairly similar to Sarton. After the death of her long-time partner, Vicky, who ran a small publishing house, sixty-year-old Harriet decides to open a women’s bookstore in a Boston suburb. She has no business acumen, just enthusiasm (and money, via the inheritance from Vicky). College girls, housewives, nuns and older feminists all become regulars, but Hatfield House also attracts unwanted attention in this dodgy neighbourhood, especially after a newspaper outs Harriet: graffiti, petty theft and worse. The police are little help, but Harriet’s brothers and a local gay couple promise to look out for her.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

Still, when I consider that Sarton was in her late seventies at the time she was writing this, and that public knowledge of AIDS would have been poor at best, I think this was admirably edgy. Harriet’s dilemma reflects Sarton’s own identity crisis, as expressed in Encore: “I do not wish to be labeled as a lesbian and do not wish to be labeled as a woman writer but consider myself a universal writer who is writing for human beings.” Nowadays, though, what Harriet deems discretion comes across as cowardice and priggishness.

While there are elements of Harriet Hatfield that have not aged well, if you focus on the Bythell-esque bookshop stuff (“I find that the people I love best are those who come in to browse, the silent shy ones, who are hungry for books rather than for conversation”) rather than the consciousness-raising or the mystery subplot, you might enjoy it as much as I did. Kudos for the first and last lines, anyway: “How rarely is it possible for anyone to begin a new life at sixty!” and “It’s the real world and I am fully alive in it.”

The Swedish Art of Ageing Well by Margareta Magnusson (#NordicFINDS23)

Annabel’s Nordic FINDS challenge is running for the second time this month. I hope to manage at least one more read for it; this one feels like a cheat as it’s not exactly in translation. Magnusson, who is Swedish, either wrote it in English or translated it herself for simultaneous 2022 publication in Sweden and the USA – where the title phrase was “Aging Exuberantly.” There is some quirky phrasing that a native speaker would never use, more so than in her Döstädning: The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning, which I reviewed last year, but it’s perfectly understandable.

The subtitle is “Life wisdom from someone who will (probably) die before you,” which gives a flavour of 89-year-old Magnusson’s self-deprecating sense of humour. The big 4-0 is coming up for me later this year, but I’ve been reading books about ageing and death since my twenties and find them valuable for gaining perspective and storing up wisdom.

This is not one of those “hygge” books extolling the virtues of Scandinavian culture, but rather a charming self-help memoir recounting what the author has learned about what matters in life and how to gracefully accept the ageing process. Each chapter is like a mini essay with a piece of advice as the title. Some are more serious than others: “Don’t Fall Over” and “Keep an Open Mind” vs. “Eat Chocolate” and “Wear Stripes.”

Since Magnusson was widowed, she has valued her friendships all the more, and during the pandemic cheerfully switched to video chats (G&T in hand) with her best friend since age eight. She is sweetly optimistic despite news headlines; after all, in the words of one of her chapter titles, “The World Is Always Ending” – she grew up during World War II and remembers the bad old days of the Cold War and personal near-tragedies like when the ship on which her teenage son was a deckhand temporarily disappeared in the South China Sea.

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Lots of little family anecdotes like that enter into the book. Magnusson has five children and lived in Singapore and Annapolis, Maryland (my part of the world!) for a time. The open-mindedness I’ve mentioned was an attitude she cultivated towards new-to-her customs like a Chinese wedding, Christian adult baptism, and Halloween. Happy memories are her emotional support; as for physical assistance: “I call my walker Lars Harald, after my husband who is no longer with me. The walker, much like my husband was, is my support and my safety.”

Volunteering, spending lots of time with younger people, looking after another living thing (a houseplant if you can’t commit to a pet), turning daily burdens into beloved routines, and keeping your hair looking as nice as possible are some of Magnusson’s top tips for coping.

An appendix gives additional death-cleaning guidance based on Covid-era FAQs; the chapter in this book that is most reminiscent of the practical approach of Döstädning is “Don’t Leave Empty-Handed,” which might sound metaphorical but in fact is a literal mantra she learned from an acquaintance. On a small scale, it might mean tidying a room gradually by picking up at least one item each time you pass through; more generally, it could refer to a mindset of cleaning up after oneself so that the world is a better place for one’s presence.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse.

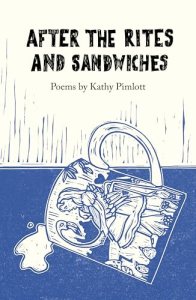

The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse. The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted.

The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted. Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour.

Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour. My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men.

My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men. I don’t often take a look at unsolicited review copies, but I couldn’t resist the title of this and I’m glad I gave it a try. Davis’s 10 stories, several of flash length, take place in small-town Kentucky and feature a lovable cast of pranksters, drunks, and spinners of tall tales. The title phrase comes from one of the controversial songs the devil-may-care narrator of “Battle Hymn” writes. My two favourites were “Kid in a Well,” about one-upmanship and storytelling in a local bar, and “The Peddlers,” which has two rogues masquerading as Mormon missionaries. I got vague Denis Johnson vibes from this sassy, gritty but funny collection; Davis is a talent!

I don’t often take a look at unsolicited review copies, but I couldn’t resist the title of this and I’m glad I gave it a try. Davis’s 10 stories, several of flash length, take place in small-town Kentucky and feature a lovable cast of pranksters, drunks, and spinners of tall tales. The title phrase comes from one of the controversial songs the devil-may-care narrator of “Battle Hymn” writes. My two favourites were “Kid in a Well,” about one-upmanship and storytelling in a local bar, and “The Peddlers,” which has two rogues masquerading as Mormon missionaries. I got vague Denis Johnson vibes from this sassy, gritty but funny collection; Davis is a talent! If you’ve read his autobiographical trilogy or seen The Durrells, you’ll be familiar with the quirky, chaotic family atmosphere that reigns in the first two pieces: “The Picnic,” about a luckless excursion in Dorset, and “The Maiden Voyage,” set on a similarly disastrous sailing in Greece (“Basically, the rule in Greece is to expect everything to go wrong and to try to enjoy it whether it does or not”). No doubt there’s some comic exaggeration at work here, especially in “The Public School Education,” about running into a malapropism-prone ex-girlfriend in Venice, and “The Havoc of Havelock,” in which Durrell, like an agony uncle, lends volumes of the sexologist’s work to curious hotel staff in Bournemouth. The final two France-set stories, however, feel like pure fiction even though they involve the factual framing device of hearing a story from a restaurateur or reading a historical manuscript that friends inherited from a French doctor. “The Michelin Man” is a cheeky foodie one with a surprisingly gruesome ending; “The Entrance” is a full-on dose of horror worthy of R.I.P. I wouldn’t say this is essential reading for Durrell fans, but it was a pleasant way of passing the time. (Secondhand – Lions Bookshop, Alnwick, 2021)

If you’ve read his autobiographical trilogy or seen The Durrells, you’ll be familiar with the quirky, chaotic family atmosphere that reigns in the first two pieces: “The Picnic,” about a luckless excursion in Dorset, and “The Maiden Voyage,” set on a similarly disastrous sailing in Greece (“Basically, the rule in Greece is to expect everything to go wrong and to try to enjoy it whether it does or not”). No doubt there’s some comic exaggeration at work here, especially in “The Public School Education,” about running into a malapropism-prone ex-girlfriend in Venice, and “The Havoc of Havelock,” in which Durrell, like an agony uncle, lends volumes of the sexologist’s work to curious hotel staff in Bournemouth. The final two France-set stories, however, feel like pure fiction even though they involve the factual framing device of hearing a story from a restaurateur or reading a historical manuscript that friends inherited from a French doctor. “The Michelin Man” is a cheeky foodie one with a surprisingly gruesome ending; “The Entrance” is a full-on dose of horror worthy of R.I.P. I wouldn’t say this is essential reading for Durrell fans, but it was a pleasant way of passing the time. (Secondhand – Lions Bookshop, Alnwick, 2021) Three suites of linked stories focus on young women whose choices in the 1980s have ramifications decades later. Chance meetings, addictions, ill-considered affairs, and random events all take their toll. Emma house-sits and waitresses while hoping in vain for her acting career to take off; “all she felt was a low-grade mourning for what she’d lost and hadn’t attained.” My favourite pair was about Nina, who is a photographer’s assistant in “Single Lens Reflex” and 13 years later, in “Photo Finish,” bumps into the photographer again in Central Park. With wistful character studies and nostalgic snapshots of changing cities, this is a stylish and accomplished collection.

Three suites of linked stories focus on young women whose choices in the 1980s have ramifications decades later. Chance meetings, addictions, ill-considered affairs, and random events all take their toll. Emma house-sits and waitresses while hoping in vain for her acting career to take off; “all she felt was a low-grade mourning for what she’d lost and hadn’t attained.” My favourite pair was about Nina, who is a photographer’s assistant in “Single Lens Reflex” and 13 years later, in “Photo Finish,” bumps into the photographer again in Central Park. With wistful character studies and nostalgic snapshots of changing cities, this is a stylish and accomplished collection. The first section contains nine linked stories about a group of five elderly female friends. Bessie jokes that “wakes and funerals are the cocktail parties of the old,” and Ruth indeed mistakes a shivah for a party and meets a potential beau who never quite successfully invites her on a date. One of their members leaves the City for a nursing home; “Sans Teeth, Sans Taste” is a good example of the morbid sense of humour. A few unrelated stories draw on Segal’s experience being evacuated from Vienna to London by Kindertransport; “Pneumonia Chronicles” is one of several autobiographical essays that bring events right up to the Covid era – closing with the bonus story “Ladies’ Zoom.” The ladies’ stories are quite amusing, but the book as a whole feels like an assortment of minor scraps; it was published when Segal, a New Yorker contributor, was 95. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop, 2023)

The first section contains nine linked stories about a group of five elderly female friends. Bessie jokes that “wakes and funerals are the cocktail parties of the old,” and Ruth indeed mistakes a shivah for a party and meets a potential beau who never quite successfully invites her on a date. One of their members leaves the City for a nursing home; “Sans Teeth, Sans Taste” is a good example of the morbid sense of humour. A few unrelated stories draw on Segal’s experience being evacuated from Vienna to London by Kindertransport; “Pneumonia Chronicles” is one of several autobiographical essays that bring events right up to the Covid era – closing with the bonus story “Ladies’ Zoom.” The ladies’ stories are quite amusing, but the book as a whole feels like an assortment of minor scraps; it was published when Segal, a New Yorker contributor, was 95. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop, 2023)

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of  This was my second Arachne Press collection after

This was my second Arachne Press collection after  A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,

A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,  I was a big fan of Katherine May’s

I was a big fan of Katherine May’s  The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this

The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this  Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction. In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible).

In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible). In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most.

In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most. Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.