Book Serendipity, January to February

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! Feel free to join in with your own.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An old woman with purple feet (due to illness or injury) in one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Someone is pushed backward and dies of the head injury in Zofia Nowak’s Book of Superior Detecting by Piotr Cieplak and one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff.

- The Hindenburg disaster is mentioned in A Long Game by Elizabeth McCracken and Evensong by Stewart O’Nan.

- Reluctance to cut into a corpse during medical school and the dictum ‘see one, do one, teach one’ in the graphic novel See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor by Grace Farris and Separate by C. Boyhan Irvine.

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

- A mention of genuine Harris tweed in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- The Katharine Hepburn film The Philadelphia Story is mentioned in The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank and Woman House by Lauren W. Westerfield.

- A mention of Icelandic poppies in Nighthawks by Lisa Martin and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Vita Sackville-West is mentioned in the Orlando graphic novel adaptation by Susanne Kuhlendahl and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Fear of bear attacks in Black Bear by Trina Moyles and Boundless by Kathleen Winter. Bears also feature in A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston and No Paradise with Wolves by Katie Stacey. [Looking through children’s picture books at the library the other week, I was struck by how many have bears in the title. Dozens!]

- I was reading books called Memory House (by Elaine Kraf) and Woman House (by Lauren W. Westerfield) at the same time, both of them pre-release books for Shelf Awareness reviews.

- An adolescent girl is completely ignorant of the facts of menstruation in I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman and Carrie by Stephen King.

- Camembert is eaten in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin.

- A herbal tonic is sought to induce a miscarriage in The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley and Bog Queen by Anna North.

- Vicks VapoRub is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson.

- An adolescent girl only admits to her distant mother that she’s gotten her first period because she needs help dealing with a stain (on her bedding / school uniform) in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel, and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin. (I had to laugh at the mother asking the narrator of the Mantel: “Have you got jam on your underskirt?”) Basically, first periods occurred a lot in this set! They are also mentioned in A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman. [I also had three abortion scenes in this cycle, but I think it would constitute spoilers to say which novels they appeared in.)

- A casual job cleaning pub/bar toilets in Kin by Tayari Jones and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Kansas City is a location mentioned in Strangers by Belle Burden, Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, and Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer. (Not actually sure if that refers to Kansas or Missouri in two of them.)

- The notion of “flirting with God” is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht.

- A signature New Orleans cocktail, the Sazerac (a variation on the whisky old-fashioned containing absinthe), appears in Kin by Tayari Jones and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- An older person’s smell brings back childhood memories in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The fact that complaining of chest pain will get you seen right away in an emergency room is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- Thickly buttered toast is a favoured snack in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

- Lime and soda is drunk in Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A husband 17 years older than his wife in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The protagonist seems to hold a special attraction for old men in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A tattoo of a pottery shard (her ex-husband’s) in Strangers by Belle Burden and one of an arrowhead (her own) in Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer.

- A relationship with an older editor at a publishing house: The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank (romantic) and Whistler by Ann Patchett (stepfather–stepdaughter).

- Repeated vomiting and a fever of 103–104°F leads to a diagnosis of appendicitis in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

- Palm crosses are mentioned in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- A Miss Jemison in Kin by Tayari Jones and a Miss Jamieson in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- Pasley as a surname in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael and a place name (Pasley Bay) in Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- A remark on a character’s unwashed hair in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A mention of a monkey’s paw in Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A character gets 26 (22) stitches in her face (head) after a car accident, a young person who’s vehemently anti-smoking, and a mention of being dusted orange from eating Cheetos, in Whistler by Ann Patchett and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Pre-eclampsia occurs in Strangers by Belle Burden and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- There’s a chapter on searching for corncrakes on the Isle of Coll (the Inner Hebrides of Scotland) in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell, which I read last year; this year I reread the essay on the same topic in Findings by Kathleen Jamie.

- Worry over women with long hair being accidentally scalped – if a horse steps on her ponytail in Mare by Emily Haworth-Booth; if trapped in a London Underground escalator in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

- A dodgy doctor who molests a young female patient in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A high school girl’s inappropriate relationship with her English teacher is the basis for Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, and then Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy, which I started soon after.

- College roommates who become same-sex lovers, one of whom goes on to have a heterosexual marriage, in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A mention of Sephora (the cosmetics shop) in Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A discussion of the Greek mythology character Leda in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Whistler by Ann Patchett (where it’s also a character name).

- A workaholic husband who rarely sees his children and leaves their care to his wife in Strangers by Belle Burden and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell.

- An apparently wealthy man who yet steals food in Strangers by Belle Burden and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Characters named Lulubelle in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Lulabelle in Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Characters named Ruth in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Doing laundry at a whorehouse in Kin by Tayari Jones and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A male character nicknamed Doll in John of John by Douglas Stuart and then Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A mention of tuberculosis of the stomach in Findings by Kathleen Jamie and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper. I was also reading a whole book on tuberculosis, Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green, at the same time.

- Mention of Doberman dogs in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman.

- Extreme fear of flying in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-June through August

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A description of the Y-shaped autopsy scar on a corpse in Pet Sematary by Stephen King and A Truce that Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews.

- Charlie Chaplin’s real-life persona/behaviour is mentioned in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus and Greyhound by Joanna Pocock.

- The manipulative/performative nature of worship leading is discussed in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and Jarred Johnson’s essay in the anthology Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia. I read one scene right after the other!

- A discussion of the religious impulse to celibacy in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- Hanif Kureishi has a dog named Cairo in Shattered; Amelia Thomas has a son by the same name in What Sheep Think About the Weather.

- A pilgrimage to Virginia Woolf’s home in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd.

- Water – Air – Earth divisions in the Nature Matters (ed. Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf) and Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthologies.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- Inappropriate sexual comments made to female bar staff in The Most by Jessica Anthony and Isobel Anderson’s essay in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology.

- Charlie Parker is mentioned in The Most by Jessica Anthony and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The metaphor of an ark for all the elements that connect one to a language and culture was used in Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis, which I read earlier in the year, and then again in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- A scene of first meeting their African American wife (one of the partners being a poet) and burning a list of false beliefs in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The Kafka quote “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us” appears in Shattered by Hanif Kureishi and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd. They also both quote Dorothea Brande on writing.

- The simmer dim (long summer light) in Shetland is mentioned in Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield and Sally Huband’s piece in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology (not surprising as they both live in Shetland!).

- A restaurant applauds a proposal or the news of an engagement in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Likeness by Samsun Knight.

- Noticing that someone ‘isn’t there’ (i.e., their attention is elsewhere) in Woodworking by Emily St. James and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and Leaving Church by Barbara Brown Taylor – which involves her literally leaving Atlanta to be the pastor of a country church – at the same time. (I was also reading Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam.)

- A mention of an adolescent girl wearing a two-piece swimsuit for the first time in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han, and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A discussion of John Keats’s concept of negative capability in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A mention of JonBenét Ramsey in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and the new introduction to Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A character drowns in a ditch full of water in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A woman who’s dying of stomach cancer in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A woman’s genitals are referred to as the “mons” in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- A girl doesn’t like her mother asking her to share her writing with grown-ups in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A girl is not allowed to walk home alone from school because of a serial killer at work in the area, and is unprepared for her period so lines her underwear with toilet paper instead in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A character named Stefan in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- A father who is a bad painter in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce.

- The goddess Minerva is mentioned in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A woman finds lots of shed hair on her pillow in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević and The Dig by John Preston.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- The narrator ponders whether she would make a good corpse in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano. The former concludes that she would, while the latter struggles to lie still during savasana (“Corpse Pose”) in yoga – ironic because she has terminal ALS.

- Harry the cat in The Wedding People by Alison Espach; Henry the cat in Calls May Be Recorded by Katharina Volckmer.

- The protagonist has a blood test after rapid weight gain and tiredness indicate thyroid problems in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- It’s said of an island that nobody dies there in Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave by Mariana Enríquez and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- A woman whose mother died when she was young and whose father was so depressed as a result that he was emotionally detached from her in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

- There’s a ghost in the cellar in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević, The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- Mention of harps / a harpist in The Wedding People by Alison Espach, The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce, and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- “You use people” is an accusation spoken aloud in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- Let’s not beat around the bush: “I want to f*ck you” is spoken aloud in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins; “Want to/Wanna f*ck?” is also in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller.

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

- A shawl is given as a parting gift in How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell and one story of What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- The author has Long Covid in Alec Finlay’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and Pluck by Adam Hughes.

- An old woman applies suncream in Kate Davis’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell.

- There’s a leper colony in What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- There’s a missionary kid in South America in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- A teen brother and sister wander the woods while on vacation with their parents in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- Using a famous fake name as an alias for checking into a hotel in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Seascraper by Benjamin Wood.

- A woman punches someone in the chest in the title story of Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

20 Books of Summer, 13–16: Tony Chan, Jen Hadfield, Kenward Anthology, Catherine Taylor

Three from my initial list (all nonfiction) and one substitute picked up at random (poetry). These are strongly place-based selections, ranging from Sheffield to Shetland and drawing on travels while also commenting on how gender and dis/ability affect daily life as well as the experience of nature.

Four Points Fourteen Lines by Tony Chan (2016)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library) ![]()

Storm Pegs: A Life Made in Shetland by Jen Hadfield (2024)

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place.

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free paperback copy for review.

From Shetland authors, I have also reviewed:

Orchid Summer by Jon Dunn (Hadfield mentions him)

Sea Bean by Sally Huband (Hadfield meets her)

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, ed. Louise Kenward (2023)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list) ![]()

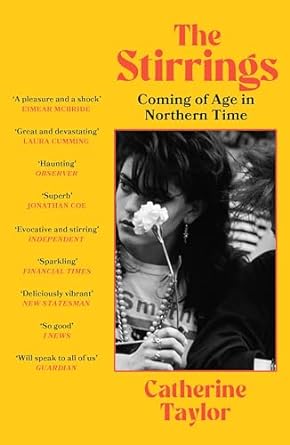

The Stirrings: Coming of Age in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor (2023)

“A typical family and an ordinary story, although neither the family nor the story seems commonplace when it is your family and your story.”

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token)

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token) ![]()

My Year in Novellas (#NovNov24)

Here at the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about the novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a special shelf of short books that I add to throughout the year. When at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, a Little Free Library, or the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about my piles for November. But I do read novellas at other times of year, too. Forty-four of them between December 2023 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year it was 46, so it seems like that’s par for the course). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My favourites of the ones I’ve already covered on the blog would probably be (nonfiction) Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti and (fiction) Aimez-vous Brahms by Françoise Sagan. My proudest achievements are: reading the short graphic novel Broderies by Marjane Satrapi in the original French at our Parisian Airbnb in December; and managing two rereads: Heartburn by Nora Ephron and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Of the short books I haven’t already reviewed here, I’ve chosen two gems, one fiction and one nonfiction, to spotlight in this post:

Fiction

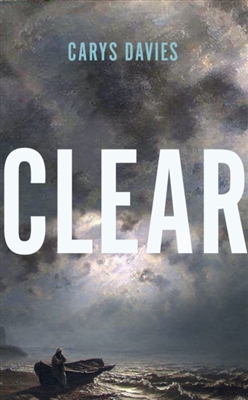

Clear by Carys Davies

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

Clear depicts the Highland Clearances in microcosm though the experiences of one man, Ivar, the last resident of a remote Scottish island between Shetland and Norway. As in a play, there is a limited setting and cast. John is a minister sent by the landowner to remove Ivar, but an accident soon after his arrival leaves him beholden to Ivar for food and care. Mary, John’s wife, is concerned and sets off on the long journey from the mainland to rescue him. Davies writes vivid scenes and brings the island’s scenery to life. Flashbacks fill in the personal and cultural history, often via objects. The Norn language is another point of interest. The deceptively simple prose captures both the slow building of emotion and the moments that change everything. It seemed the trio were on course for tragedy, yet they are offered the grace of a happier ending.

In my book club, opinions differed slightly as to the central relationship and the conclusion, but we agreed that it was beautifully done, with so much conveyed in the concise length. This received our highest rating ever, in fact. I’d read Davies’ West and not appreciated it as much, although looking back I can see that it was very similar: one or a few character(s) embarked on unusual and intense journey(s); a plucky female character; a heavy sense of threat; and an improbably happy ending. It was the ending that seemed to come out of nowhere and wasn’t in keeping with the tone of the rest of the novella that made me mark West down. Here I found the writing cinematic and particularly enjoyed Mary as a strong character who escaped spinsterhood but even in marriage blazes her own trail and is clever and creative enough to imagine a new living situation. And although the ending is sudden and surprising, it nevertheless seems to arise naturally from what we know of the characters’ emotional development – but also sent me scurrying back to check whether there had been hints. One of my books of the year for sure. ![]()

Nonfiction

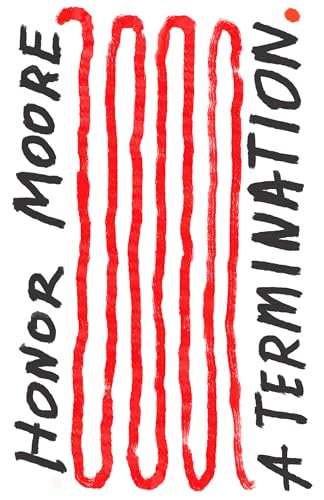

A Termination by Honor Moore

Poet and memoirist Honor Moore’s A Termination is a fascinatingly discursive memoir that circles her 1969 abortion and contrasts societal mores across her lifetime.

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

During the spring in question, Moore was a 23-year-old drama school student. Her lover, L, was her professor. But she also had unwanted sex with a photographer. She did not know which man had impregnated her, but she did know she didn’t feel prepared to become a mother. She convinced a psychiatrist that doing so would destroy her mental health, and he referred her to an obstetrician for a hospital procedure. The termination was “my first autonomous decision,” Moore insists, a way of saying, “I want this life, not that life.”

Family and social factors put Moore’s experiences into perspective. The first doctor she saw refused Moore’s contraception request because she was unmarried. Her mother, however, bore nine children and declined to abort a pregnancy when advised to do so for medical reasons. Moore observes that she made her own decision almost 10 years before “the word choice replaced pro abortion.”

This concise work is composed of crystalline fragments. The stream of consciousness moves back and forth in time, incorporating occasional second- and third-person narration as well as highbrow art and literature references. Moore writes one scene as if it’s in a play and imagines alternative scenarios in which she has a son; though she is curious, she is not remorseful. The granular attention to women’s lives recalls Annie Ernaux, while the kaleidoscopic yet fluid approach is reminiscent of Sigrid Nunez’s work. It’s a stunning rendering of steps on her childfree path. ![]()

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I currently have four novellas underway and plan to start some more this weekend. I have plenty to choose from!

Everyone’s getting in on the act: there’s an article on ‘short and sweet books’ in the November/December issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I’m an associate editor; Goodreads sent around their usual e-mail linking to a list of 100 books under 250 or 200 pages to help readers meet their 2024 goal. Or maybe you’d like to join in with Wafer Thin Books’ November buddy read, the Ugandan novella Waiting by Goretti Kyomuhendo (2007).

Why not share some recent favourite novellas with us in a post of your own?

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in  And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?

And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:  I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022) Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with  It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

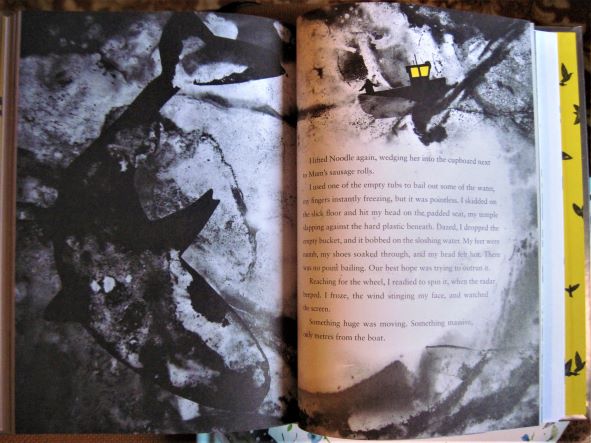

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.