#WITMonth, II: Bélem, Blažević, Enríquez, Lebda, Pacheco and Yu (#17 of 20 Books)

Catching up with my Women in Translation month coverage, which concluded (after Part I, here) with five more short novels ranging from historical realism to animal-oriented allegory, plus a travel book.

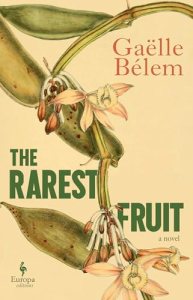

The Rarest Fruit, or The Life of Edmond Albius by Gaëlle Bélem (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Hildegarde Serle]

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

With thanks to Europa Editions, who sent an advanced e-copy for review.

In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Croatian by Anđelka Raguž]

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

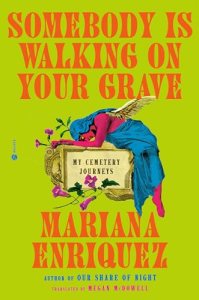

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez (2013; 2025)

[Translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell]

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones]

Like the Blažević, this is an impressionistic, pastoral work that contrasts vitality and decay in short chapters of one to three pages. The narrator is a young woman staying in her grandmother’s house and caring for her while she is dying of cancer; “now is not the time for life. Death – that’s what fills my head. I’m at its service. Grandma is my child. I am my grandmother’s mother. And that’s all right, I think.” The house has just four inhabitants – the narrator, Grandma Róża, Grandpa, and Ann – and seems permeable: to the cold, to nature. Animals play a large role, whether pets, farmed or wild. There’s Danube the hound, the cows delivered to the nearby slaughterhouse, and a local vixen with whom the narrator identifies.

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

In all three Linden Editions books I’ve read, the translator’s afterword has been particularly illuminating. I thought I was missing something, but Lloyd-Jones reassured me it’s unclear who Ann is: sister? friend? lover? (I was sure I spotted some homoerotic moments.) Lloyd-Jones believes she’s the mirror image of the narrator, leaning toward life while the narrator – who has endured sexual molestation and thyroid problems – tends towards death. The animal imagery reinforces that dichotomy.

The narrator and Ann remark that it feels like Grandma has been ill for a million years, but they also never want this time to end. The novel creates that luminous, eternal present. It was the best of this bunch.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews:

Pandora by Ana Paula Pacheco (2023; 2025)

[Translated from Portuguese by Julia Sanches]

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

#17 of my 20 Books of Summer:

Invisible Kitties by Yu Yoyo (2021; 2024)

[Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang]

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

I’m really pleased with myself for covering a total of 8 books for this challenge, each one translated from a different language!

Which of these would you read?

Most Anticipated Books of the Second Half of 2025

My “Most Anticipated” designation sometimes seems like a kiss of death, but other times the books I choose for these lists live up to my expectations, or surpass them!

(Looking back at the 25 books I selected in January, I see that so far I have read and enjoyed 8, read but been disappointed by 4, not yet read – though they’re on my Kindle or accessible from the library – 9, and not managed to get hold of 4.)

This time around, I’ve chosen 15 books I happen to have heard about that will be released between July and December: 7 fiction and 8 nonfiction. (In release date order within genre. UK release information generally given first, if available. Note given on source if I have managed to get hold of it already.)

Fiction

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

Nonfiction

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

As a bonus, here are two advanced releases that I reviewed early:

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists.

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists. ![]()

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans.

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans. ![]()

I can also recommend:

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, ed. Denne Michele Norris [Aug. 12, HarperOne / 25 Sept., HarperCollins] (Review to come for Shelf Awareness) ![]()

Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade [Sept. 2, Univ. of Florida Press] (Review pending for Foreword) ![]()

Which of these catch your eye? Any other books you’re looking forward to in this second half of the year?

Winter Reads, I: Michael Cunningham & Helen Moat

It’s been feeling springlike in southern England with plenty of birdsong and flowers, yet cold weather keeps making periodic returns. (For my next instalment of wintry reads, I’ll try to attract some snow to match the snowdrops by reading three “Snow” books.) Today I have a novel drawing on a melancholy Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale and a nature/travel book about learning to appreciate winter.

The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham (2014)

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

Of course, Cunningham takes inspiration, thematically and linguistically, from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale about love and conversion, most obviously in an early dreamlike passage about Tyler letting snow swirl into the apartment through the open windows:

He returns to the window. If that windblown ice crystal meant to weld itself to his eye, the transformation is already complete; he can see more clearly now with the aid of this minuscule magnifying mirror…

I was most captivated by the early chapters of the novel, picking it up late one night and racing to page 75, which is almost unheard of for me. The rest took me significantly longer to get through, and in the intervening five weeks or so much of the detail has evaporated. But I remember that I got Chris Adrian and Julia Glass vibes from the plot and loved the showy prose. (And several times while reading I remarked to people around me how ironic it was that these characters in a 2014 novel are so outraged about Dubya’s re-election. Just you all wait two years, and then another eight!)

I fancy going on a mini Cunningham binge this year. I plan to recommend The Hours for book club, which would be a reread for me. Otherwise, I’ve only read his travel book, Land’s End. I own a copy of Specimen Days and the library has Day, but I’d have to source all the rest secondhand. Simon of Stuck in a Book is a big fan and here are his rankings. I have some great stuff ahead! (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

While the Earth Holds Its Breath: Embracing the Winter Season by Helen Moat (2024)

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

There were many incidents and emotions I could relate to here – a walk on the canal towpath always makes me feel better, and the car-heavy lifestyle I resume on trips to America feels unnatural.

Days are where we must live, but it didn’t have to be a prison of house and walls. I needed the rush of air, the slap of wind on my cheeks. I needed to feel alive. Outdoors.

I’d never liked the rain, but if I were to grow to love winters on my island, I had to learn to love wet weather, go out in it.

What can there be but winter? It belongs to the circle of life. And I belonged to winter, whether I liked it or not. Indoors, or moving from house to vehicle and back to house again, I lost all sense of my place on this Earth. This world would be my home for just the smallest of moments in the vastness of time, in the turning of the seasons. It was a privilege, I realised.

However, the content is repetitive such that the three-year cycle doesn’t add a lot and the same sorts of pat sentences about learning to love winter recur. Were the timeline condensed, there might have been more of a focus on the more interesting travel segments, which also include France and Scotland. So many have jumped on the Wintering bandwagon, but Katherine May’s book felt fresh in a way the others haven’t.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

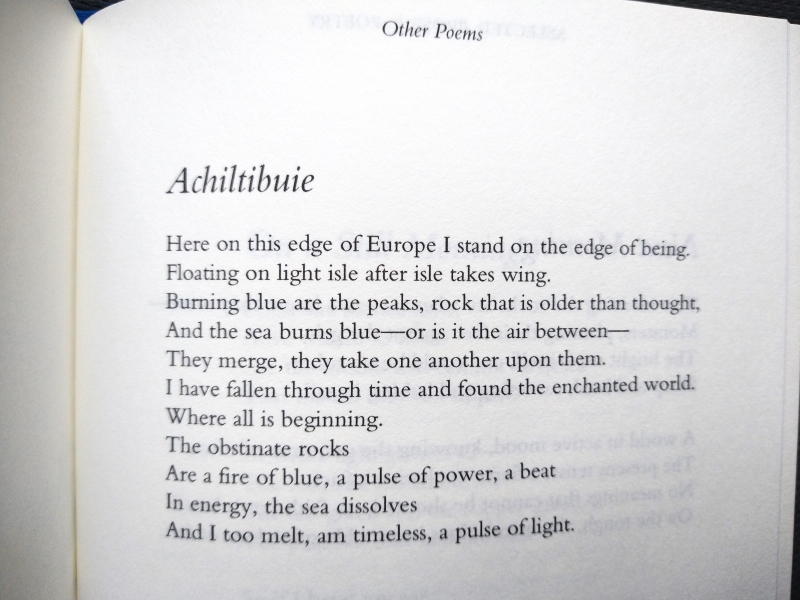

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

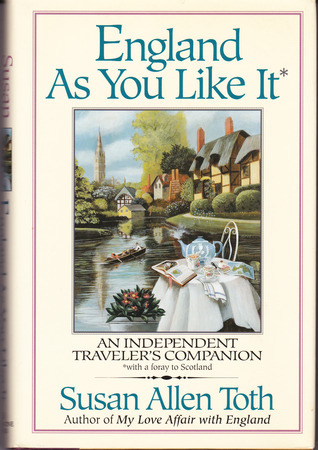

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Review Catch-up: Matt Gaw, Sheila Heti, Liz Jensen (and a Pile of DNFs)

Today I have a travel book about appreciating nature in any weather, a sui generis memoir drawn from a decade of diaries, and an impassioned cry for the environment in the wake of a young adult son’s death.

I’m also bidding farewell to a whole slew of review books that have been hanging around, in some cases, for literal years – I think one is from 2021, and several others from 2022. Putting a book on my “set aside” shelf can be a kiss of death … or I can go back at a better time and end up loving it. It’s hard to predict which will occur. On these, alas, I have had to admit defeat and will pass the books on to other homes.

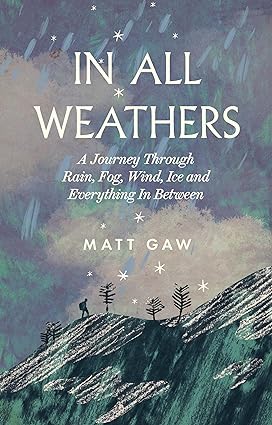

In All Weathers: A Journey through Rain, Fog, Wind, Ice and Everything in Between by Matt Gaw

Gaw’s two previous nature/travel memoirs, the enjoyable The Pull of the River and Under the Stars, involve gentle rambles through British landscapes, along with commentary on history, nature and science. The remit is much the same here. The book is split into four long sections: “Rain,” “Fog,” “Ice and Snow,” and “Wind.” The adventures always start from and end up at the author’s home in Suffolk, but he ranges as far as the Peak District, Cumbria and the Isle of Skye. Wild swimming is one way in which he experiences places. He notices a lot and describes it all in lovely and relatable prose.

I was tickled by the definitions of, and statistics about, a “white Christmas”: in the UK, it counts if there’s even a single snowflake falling, whereas in the US there has to be 2.5 cm or more of standing snow. (Scotland is most likely to experience white Christmases; it has had 37 since 1960 vs. 26 in northern England. The English snow record is 43 cm, at Buxton and Malham Tarn in 1981 and 2009.) There’s underlying mild dread as he notes how weather patterns have changed and will likely continue changing, ever more dramatically, into his children’s future.

I was tickled by the definitions of, and statistics about, a “white Christmas”: in the UK, it counts if there’s even a single snowflake falling, whereas in the US there has to be 2.5 cm or more of standing snow. (Scotland is most likely to experience white Christmases; it has had 37 since 1960 vs. 26 in northern England. The English snow record is 43 cm, at Buxton and Malham Tarn in 1981 and 2009.) There’s underlying mild dread as he notes how weather patterns have changed and will likely continue changing, ever more dramatically, into his children’s future.

I find I don’t have much to say about this book because it is very nice but doesn’t do anything interesting or tackle anything that isn’t familiar from many other nature books (such as Rain by Melissa Harrison and Forecast by Joe Shute). It’s unfortunate for Gaw that his ideas often seem to have been done before – his book on night-walking, in particular, was eclipsed by several other works on that topic that came out at around the same time. I hope that the next time around he’ll get more editorial guidance to pursue original topics. It might take just a little push to get him to the next level where he could compete with top UK nature writers.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson Books for the free copy for review.

Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti

Heti put the contents of ten years of her diaries into a spreadsheet, alphabetizing each sentence (including articles), and then ruthlessly culled the results until she had a 25-chapter (no ‘X’) book. You could hardly call it a narrative, yet looking for one is so hardwired that every few sentences you are jolted out of what feels like a mini-story and into something new. Instead, you might think of it as an autobiographical mosaic. The recurring topics are familiar from the rest of Heti’s oeuvre, with obsessive cogitating about relationships, art and identity. But there are also the practicalities of trying to make a living as a woman in a creative profession. Tendrils of the everyday poke out here and there as she makes a meal, catches a plane, or buys clothes. Men loom large: explicit accounts of sex with Pavel and Lars (though also Fiona); advising her friend Lemons on his love life. There are also meta musings on what she is trying to achieve with her book projects and on what literature can be.

Grammatically, the document is a lot more interesting than it could be – or than a similar experiment based on my diary would be, for instance – because Heti sometimes writes in incomplete sentences, dropping the initial pronoun; or intersperses rhetorical questions or notes to self in the imperative. So, yes, ‘I’ is a long chapter, but not only because of self-absorbed “I…” statements; there’s also plenty of “If…” and “It’s…” ‘H’ and ‘W’ are longer sections than might be expected because of the questioning mode. But it’s at the sentence level that the book makes the biggest impression: lines group together, complement or contradict each other, or flout coherence by being so merrily à propos of nothing. Here are a few passages to give a flavour:

Grammatically, the document is a lot more interesting than it could be – or than a similar experiment based on my diary would be, for instance – because Heti sometimes writes in incomplete sentences, dropping the initial pronoun; or intersperses rhetorical questions or notes to self in the imperative. So, yes, ‘I’ is a long chapter, but not only because of self-absorbed “I…” statements; there’s also plenty of “If…” and “It’s…” ‘H’ and ‘W’ are longer sections than might be expected because of the questioning mode. But it’s at the sentence level that the book makes the biggest impression: lines group together, complement or contradict each other, or flout coherence by being so merrily à propos of nothing. Here are a few passages to give a flavour:

Am I wasting my time? Am low on money. Am making noodles. Am reading Emma. Am tired and will go to sleep. Am tired today and I feel like I may be getting a cold. Ambivalence gives you something to do, something to think about.

Best not to live too emotionally in the future—it hardly ever comes to pass. Better to be on the outside, where you have always been, all your life, even in school, nothing changes. Better to look outward than inward. Blow jobs and tenderness. Books that fall in between the cracks of all aspects of the human endeavour.

It’s 2:34 every time I check the time these days. It’s 4 p.m. It’s 4:41 now. It’s a fantasy of being saved. It’s a stupid idea. It’s a yellow, cloudy sky. It’s amazing to me how life keeps going. It’s better to work, to go into the underground cave where there are books, than to fritter away time online. It’s crazy that I need all of these mental crutches in order to live. It’s fiction. It’s fine.

Scrambled eggs on toast at Yaddo. Second-guessing everything. Second, he said that no one is buying fiction. See the complexity. See the souls. See what kind of story the book can accommodate, if any. Seeing her for coffee was not so bad.

It’s surprising how much sense a text constructed so apparently haphazardly makes, perhaps because of the same subject and style throughout. Sometimes aphoristic, sometimes poetic (all that anaphora), the book is playful but overall serious about the capturing of a life on the page. Heti transcends the quotidian by exploding the one-thing-after-another tedium of chronology. Remarkably, the collage approach produces a more genuine, crystalline vision of the self than precise scenes and cause-and-effect chains ever could. A work of life writing like no other, it must be read in a manner all its own that it teaches you as you go along. I admire it enormously and hope I might write something even half as daring one day.

With thanks to Fitzcarraldo Editions for the free copy for review.

Your Wild and Precious Life: On grief, hope and rebellion by Liz Jensen

Jensen’s younger son, Raphaël Coleman, was just 25 when he collapsed while filming a documentary in South Africa and died of a previously undiagnosed heart condition. Raph had been involved in Extinction Rebellion and Jensen is a founding member of Writers Rebel. They both deemed activism “the best antidote to depression.” Her son had been obsessed with wildlife from a young age and was rewilding acres of their land in France, as well as making environmentalist films (he had achieved minor fame as a child actor in Nanny McPhee) and participating in direct action, such as at the Brazilian embassy in London.

For Jensen, the challenge, especially after lockdown confined her to her Copenhagen flat, was to channel grief into further radicalism rather than retreating into herself or giving in to the lure of suicide. She tried to see personal grief as a reminder of ecogrief, and therefore as a spur. One way that she coped was turning towards the supernatural. She continued to hear and speak to Raph, in daily life as well as through a medium, and interpreted bird sightings as signs of his continued presence. An additional point of interest to me was that the author’s husband is Carsten Jensen, the writer of one of my favourite books, We, the Drowned.

For Jensen, the challenge, especially after lockdown confined her to her Copenhagen flat, was to channel grief into further radicalism rather than retreating into herself or giving in to the lure of suicide. She tried to see personal grief as a reminder of ecogrief, and therefore as a spur. One way that she coped was turning towards the supernatural. She continued to hear and speak to Raph, in daily life as well as through a medium, and interpreted bird sightings as signs of his continued presence. An additional point of interest to me was that the author’s husband is Carsten Jensen, the writer of one of my favourite books, We, the Drowned.

This doesn’t particularly stand out among the dozens of bereavement memoirs I’ve read. (It was also remarkably similar to Alexandra Fuller’s Fi, which I’d read not long before.) Perhaps more years of reflection would have helped – Mary Karr advises seven – though I suspect Jensen felt, quite rightly, that given the current state of the environment we have no time to waste. And I have no doubt that the combination of a mother’s love and an ecological conscience will make this book meaningful to many readers.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

And the DNFs…

there are more things, Yara Rodrigues Fowler – I loved Stubborn Archivist so much that I leapt at the chance to read her follow-up, but it was just too dull and involved about Brazilian versus UK politics. Nor did the stylistic tricks feel as novel this time around. I read 66 pages. (Fleet)

The Rabbit Hutch, Tess Gunty – Gunty dazzled critics and prize judges in the USA, winning a National Book Award. I was drawn to her debut novel for the composite picture of the residents of one Indiana apartment building and the strange connections that develop between them over one summer week, including perhaps a murder? Blandine, the central character, is a sort of modern-day mystic but hard to warm to (“She normally tries to avoid saying in which out loud, to minimize the number of people who find her insufferable”), as are all the characters. This felt like try-hard MFA writing. I read 85 pages. (Oneworld)

Eve: The Disobedient Future of Birth, Claire Horn – I usually get on well with Wellcome Collection books. I think the problem here was that there was too much material that was familiar to me from having read Womb by Leah Hazard – even the SF-geared stuff about artificial wombs. I read 45 pages. (Profile Books)

Blessings, Chukwuebuka Ibeh – This debut novel has a confident voice, buttressed by determination to reveal what life is like for queer people living in countries where homosexuality is criminalized. Obiefuna is cast out for having a crush on Aboy, his father’s apprentice, even though the two young men share nothing more physical than a significant gaze into each other’s eyes. The strict boarding school his father sends him to is a place of privation, hierarchy, hazing and, I suspect, same-sex experimentation. I found the writing capable but couldn’t get past a sense of dread about what was going to happen. Meanwhile, I didn’t think the alternating chapters from Obiefuna’s mother’s perspective added anything to the narrative. I read 62 pages. (Penguin Viking)

The War for Gloria, Atticus Lish – Lish’s debut novel, Preparation for the Next Life, was excellent, but I could never get stuck in to this follow-up, despite the appealing medical theme. When Gloria Goltz is diagnosed with ALS, her 15-year-old son Corey turns to his absent father and others for support. It was also unfortunate that Lish mentions the Ice Bucket Challenge: that was popularized in 2014, whereas the book is set in 2010. I read 75 pages. (Serpent’s Tail)

Snow Widows: Scott’s Fatal Antarctic Expedition through the Eyes of the Women They Left Behind, Katherine MacInnes – I seriously overestimated my interest in polar exploration narratives. MacInnes seems to have done quite a good job of creating novelistic scenes through research, though. I read 35 pages. (William Collins)