#NovNov25 Catch-Up: Dodge, Garner, O’Collins, Sagan and A. White

As promised, I’m catching up on five novella-length works I finished in November. In fiction, I have an odd duck of a family story, a piece of autofiction about caring for a friend with cancer, a record of an affair, and a tale of settling two new cats into home life in the 1950s. And in nonfiction, a short book about the religious approach to midlife crisis.

Fup by Jim Dodge (1983)

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages]

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages] ![]()

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (2008)

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages]

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages] ![]()

Second Journey: Spiritual Awareness and the Mid-Life Crisis by Gerald O’Collins SJ (1978; 1995)

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages]

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages] ![]()

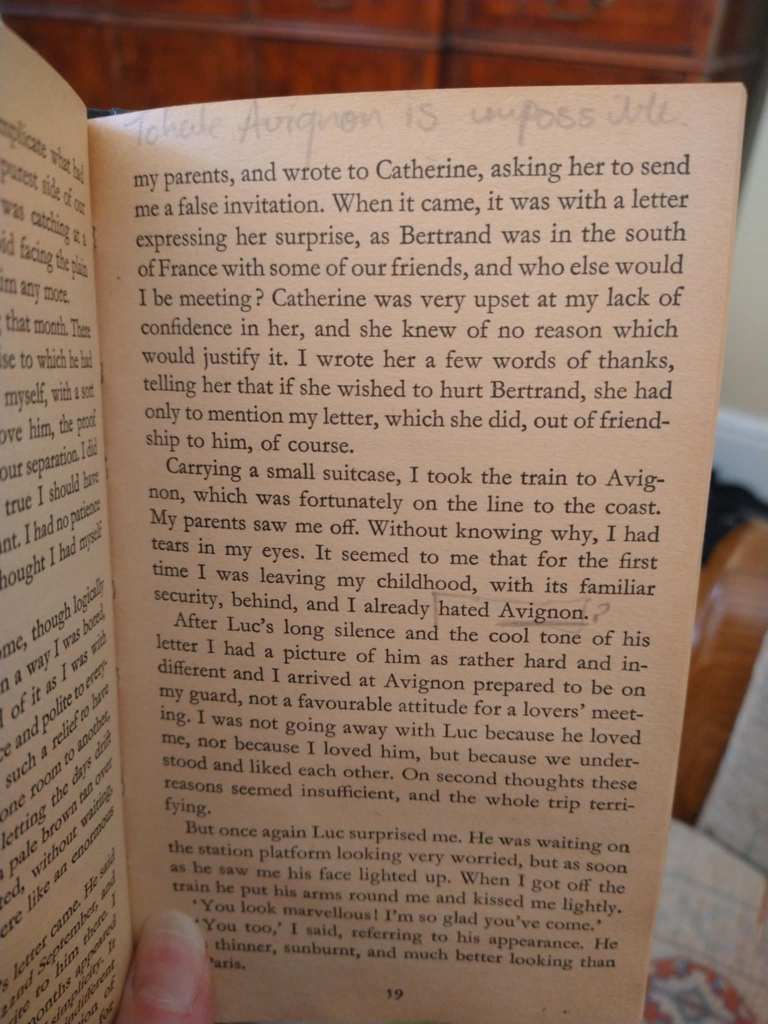

A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan (1956)

[Translated from French by Irene Ash]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages] ![]()

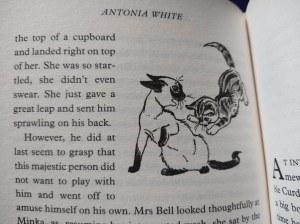

Minka and Curdy by Antonia White; illus. Janet and Anne Johnstone (1957)

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages]

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages] ![]()

I also had a few DNFs last month:

- The Book of Colour by Julia Blackburn (1995) seemed a good bet because I’ve enjoyed some of Blackburn’s nonfiction and it was on the Orange Prize shortlist. But after 60 pages I still had no idea what was going on amid the Mauritius-set welter of family history and magic realism. (Secondhand – Bas Books charity shop, 2022)

- A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood (1964) lured me because I’d so loved Goodbye to Berlin and I remember liking the Colin Firth film. But this story of an Englishman secretly mourning his dead partner while trying to carry on as normal as a professor in Los Angeles was so dreary I couldn’t persist. (Public library)

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel (2025) – JLS could write one of these mini nature volumes in his sleep. (Maybe he did with this one, actually?) I’d rather one full-length book from him every few years than bitty, redundant ones annually. (Public library)

- Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse (1974) – I’ve read one Jeeves & Wooster book before and enjoyed it well enough. This felt inconsequential, so as I already had way too many novellas on the go I sent it back whence it came. (Little Free Library)

Final statistics for #NovNov25 coming up tomorrow!

Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

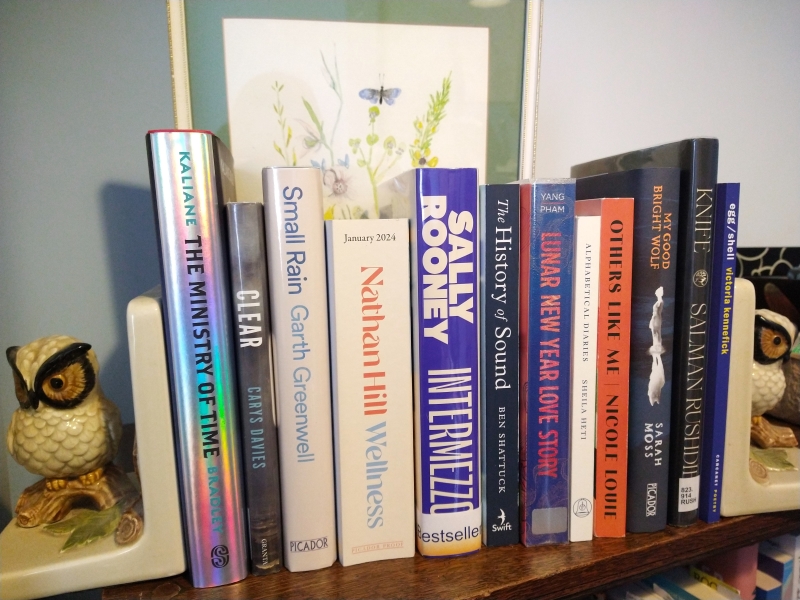

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

Carol Shields Prize Reading: Daughter and Dances

Two more Carol Shields Prize nominees today: from the shortlist, the autofiction-esque story of a father and daughter, both writers, and their dysfunctional family; and, from the longlist, a debut novel about the physical and emotional rigours of being a Black ballet dancer.

Daughter by Claudia Dey

Like her protagonist, Mona Dean, Dey is a playwright, but the Canadian author has clearly stated that her third novel is not autofiction, even though it may feel like it. (Fragmentary sections, fluidity between past and present, a lack of speech marks; not to mention that Dey quotes Rachel Cusk and there’s even a character named Sigrid.) Mona’s father, Paul, is a serial adulterer who became famous for his novel Daughter and hasn’t matched that success in the 20 years since. He left Mona and Juliet’s mother, Natasha, for Cherry, with whom he had another daughter, Eva. There have been two more affairs. Every time Mona meets Paul for a meal or a coffee, she’s returned to a childhood sense of helplessness and conflict.

I had a sordid contract with my father. I was obsessed with my childhood. I had never gotten over my childhood. Cherry had been cruel to me as a child, and I wanted to get back at Cherry, and so I guarded my father’s secrets like a stash of weapons, waiting for the moment I could strike.

It took time for me to warm to Dey’s style, which is full of flat, declarative sentences, often overloaded with character names. The phrasing can be simple and repetitive, with overuse of comma splices. At times Mona’s unemotional affect seems to be at odds with the melodrama of what she’s recounting: an abortion, a rape, a stillbirth, etc. I twigged to what Dey was going for here when I realized the two major influences were Hemingway and Shakespeare.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

And then there’s the King Lear setup. (I caught on to this late, perhaps because I was also reading a more overt Lear update at the time, Private Rites by Julia Armfield.) The larger-than-life father; the two older daughters and younger half-sister; the resentment and estrangement. Dey makes the parallel explicit when Mona, musing on her Hemingway-inspired oeuvre, asks, “Why had Shakespeare not called the play King Lear’s Daughters?”

Were it not for this intertextuality, it would be a much less interesting book. And, to be honest, the style was not my favourite. There were some lines that really irked me (“The flowers they were considering were flamboyant to her eye, she wanted less flamboyant flowers”; “Antoine barked. He was barking.”; “Outside, it sunned. Outside, it hailed.”). However, rather like Sally Rooney, Dey has prioritized straightforward readability. I found that I read this quickly, almost as if in a trance, inexorably drawn into this family’s drama. ![]()

Related reads: Monsters by Claire Dederer, The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright, The Wife by Meg Wolitzer, Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Farrar, Straus and Giroux for the free e-copy for review.

Also from the shortlist:

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Longlisted:

Dances by Nicole Cuffy

This was a buddy read with Laura (see her review); I think we both would have liked to see it on the shortlist as, though we’re not dancers ourselves, we’re attracted to the artistry and physicality of ballet. It’s always a privilege to get an inside glimpse of a rarefied world, and to see people at work, especially in a field that requires single-mindedness and self-discipline. Cuffy’s debut novel focuses on 22-year-old Celine Cordell, who becomes the first Black female principal in the New York City Ballet. Cece marvels at the distance between her Brooklyn upbringing – a single mother and drug-dealing older brother, Paul – and her new identity as a celebrity who has brand endorsements and gets stopped on the street for selfies.

Even though Kaz, the director, insists that “Dance has no race,” Cece knows it’s not true. (And Kaz in some ways exaggerates her difference, creating a role for her in a ballet based around Gullah folklore from South Carolina.) Cece has always had to work harder than the others in the company to be accepted:

Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

A further complication is her relationship with Jasper, her white dance partner. It’s an open secret in the company that they’re together, but to the press they remain coy. Cece’s friends Irine and Ryn support her through rocky times, and her former teachers, Luca and Galina, are steadfast in their encouragement. Late on, Cece’s search for Paul, who has been missing for five years, becomes a surprisingly major element. While the sibling bond helps the novel stand out, I most enjoyed the descriptions of dancing. All of the sections and chapters are titled after ballet terms, and even when I was unfamiliar with the vocabulary or the music being referenced, I could at least vaguely picture all the moves in my head. It takes real skill to render other art forms in words. I’ll look forward to following Cuffy’s career. ![]()

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and One World for the free e-copy for review.

Currently reading:

(Shortlist) Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote

(Longlist) Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad

Up next:

(Longlist) You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy

I’m aiming for one more batch of reviews (and a prediction) before the winner is announced on 13 May.

Women’s Prize 2022: Longlist Wishes vs. Predictions

Next Tuesday the 8th, the 2022 Women’s Prize longlist will be announced.

First I have a list of 16 novels I want to be longlisted, because I’ve read and loved them (or at least thought they were interesting), or am currently reading and enjoying them, or plan to read them soon, or am desperate to get hold of them.

Wishlist

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (my review)

Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth (my review)

These Days by Lucy Caldwell

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson – currently reading

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González – currently reading

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall (my review)

Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny (my review)

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (my review)

Devotion by Hannah Kent – currently reading

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – currently reading

When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain (my review)

The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka – review coming to Shiny New Books on Thursday

Brood by Jackie Polzin (my review)

The Performance by Claire Thomas (my review)

Then I have a list of 16 novels I think will be longlisted mostly because of the buzz around them, or they’re the kind of thing the Prize always recognizes (like danged GREEK MYTHS), or they’re authors who have been nominated before – previous shortlistees get a free pass when it comes to publisher submissions, you see – or they’re books I might read but haven’t gotten to yet.

Predictions

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Second Place by Rachel Cusk (my review)

Matrix by Lauren Groff

Free Love by Tessa Hadley

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris (my review)

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

The Fell by Sarah Moss (my review)

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney (my review)

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

Still Life by Sarah Winman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara – currently reading

*A wildcard entry that could fit on either list: Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason (my review).*

Okay, no more indecision and laziness. Time to combine these two into a master list that reflects my taste but also what the judges of this prize generally seem to be looking for. It’s been a year of BIG books – seven of these are over 400 pages; three of them over 600 pages even – and a lot of historical fiction, but also some super-contemporary stuff. Seven BIPOC authors as well, which would be an improvement over last year’s five and closer to the eight from two years prior. A caveat: I haven’t given thought to publisher quotas here.

MY WOMEN’S PRIZE FORECAST

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González

Matrix by Lauren Groff

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Devotion by Hannah Kent

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith

The Fell by Sarah Moss

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

What do you think?

See also Laura’s, Naty’s, and Rachel’s predictions (my final list overlaps with theirs on 10, 5 and 8 titles, respectively) and Susan’s wishes.

Just to further overwhelm you, here are the other 62 eligible 2021–22 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut:

In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lola Akinmade Åkerström

Violeta by Isabel Allende

The Leviathan by Rosie Andrews

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

The Stars Are Not Yet Bells by Hannah Lillith Assadi

The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore

Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau

Defenestrate by Renee Branum

Songs in Ursa Major by Emma Brodie

Assembly by Natasha Brown

We Were Young by Niamh Campbell

The Raptures by Jan Carson

A Very Nice Girl by Imogen Crimp

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

Love & Saffron by Kim Fay

Mrs March by Virginia Feito

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

Tides by Sara Freeman

I Couldn’t Love You More by Esther Freud

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge

Listening Still by Anne Griffin

The Twyford Code by Janice Hallett

Mrs England by Stacey Halls

Three Rooms by Jo Hamya

The Giant Dark by Sarvat Hasin

The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

Violets by Alex Hyde

Fault Lines by Emily Itami

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda

Notes on an Execution by Danya Kukafka

Paul by Daisy Lafarge

Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

The Truth About Her by Jacqueline Maley

Wahala by Nikki May

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors

The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico

The Vixen by Francine Prose

The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Cut Out by Michèle Roberts

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross

Secrets of Happiness by Joan Silber

Cold Sun by Anita Sivakumaran

Hear No Evil by Sarah Smith

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

Animal by Lisa Taddeo

Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan

Lily by Rose Tremain

French Braid by Anne Tyler

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

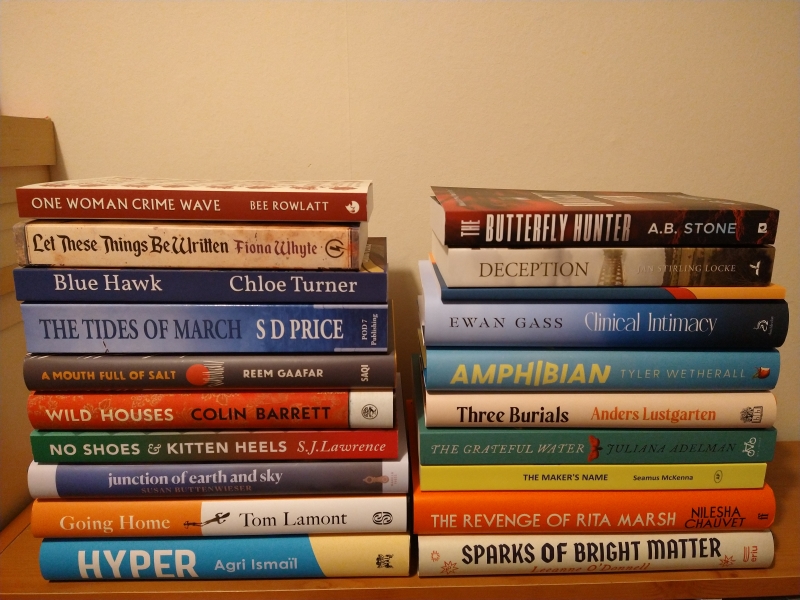

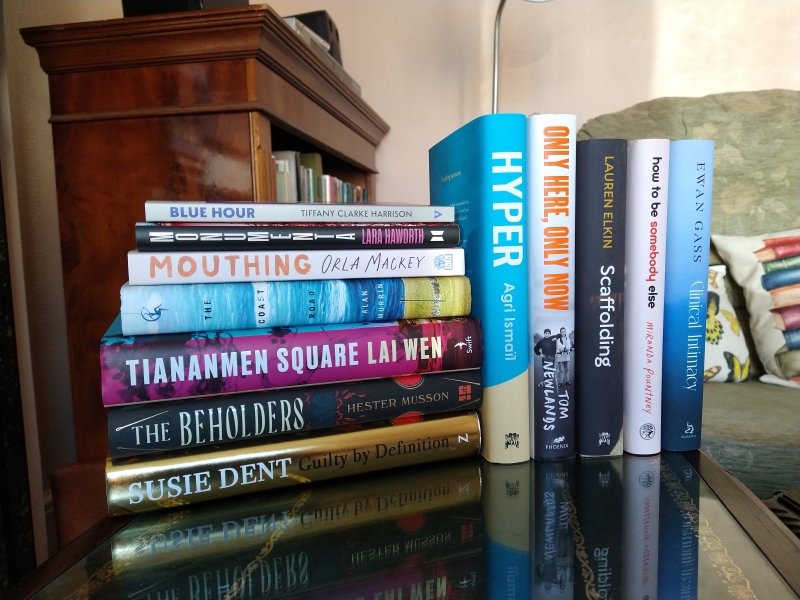

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

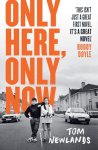

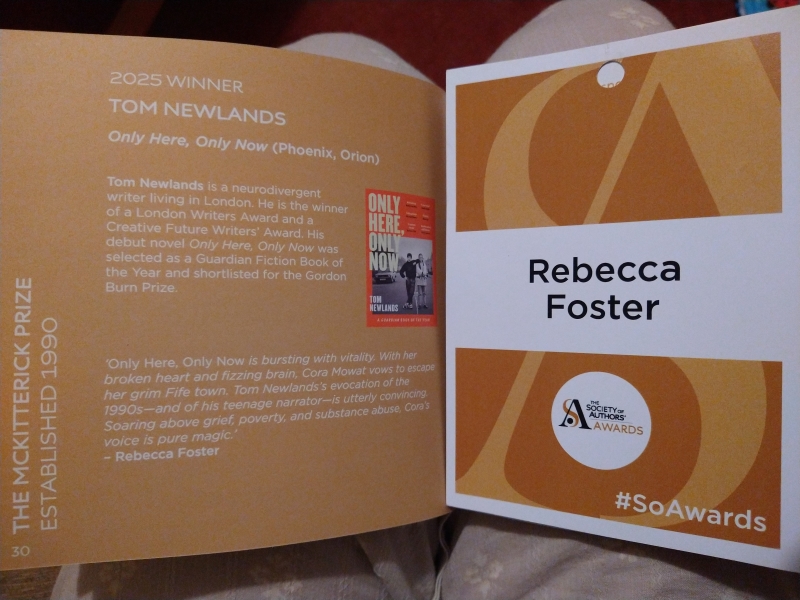

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

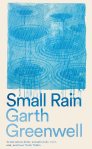

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction. In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible).

In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible). In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most.

In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most. Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die. The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s  These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.