Tag Archives: Barbara Pym

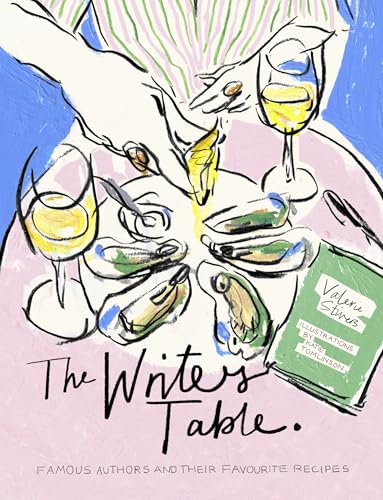

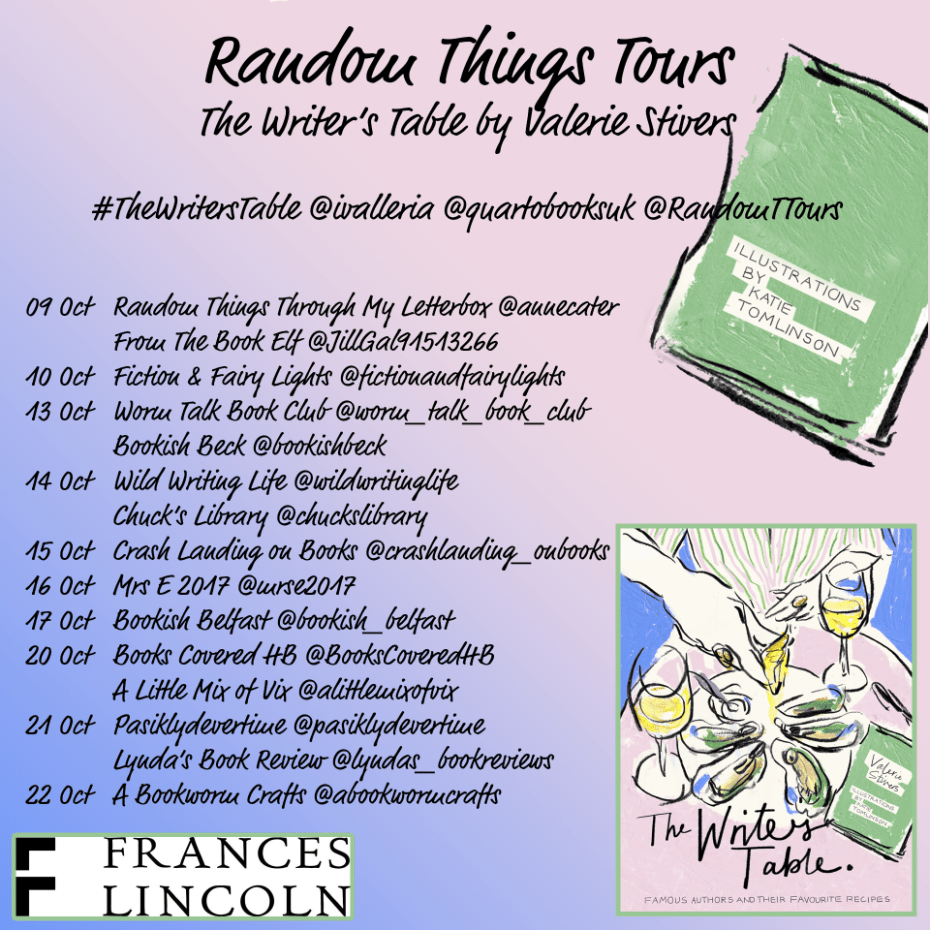

The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers (Blog Tour)

In 2017, Valerie Stivers started writing about food in classic fiction for The Paris Review. Her particular project for the “Eat Your Words” column would be cooking and baking her way through literature. It was a larger undertaking than she realized and became something of an obsession. A selection of the greatest hits made it into The Writer’s Table. Each few-page biographical profile opens with a recipe drawn from that author’s work or developed by Stivers. A surprising number of writers published cookbooks – or had one compiled after their death – including Maya Angelou, Jane Austen (of family friend and housekeeper Martha Lloyd’s recipes), Ernest Hemingway, Barbara Pym, George Sand and Alice B. Toklas.

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

The alphabetical arrangement of the pieces emphasizes the wide range of eras, regions, and genres. It’s a fun book for browsing, though I might have liked more depth on fewer authors. I especially liked the listicles on “Writers’ Favourite Cocktails” – E.B. White’s triple-strength gin martinis sound lethal! – and “Writers Who Didn’t Eat Proper Meals.” Proust subsisted on croissants and café au lait, while Highsmith ate nothing but bacon and eggs (hers being mostly a liquid diet). Katie Tomlinson’s colourful sketches are delightful. I enjoyed having this around to flick through and can recommend it as a gift for the literary foodie in your life.

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and Frances Lincoln (Quarto Books) for the free copy for review.

Buy The Writer’s Table from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was pleased to be part of the blog tour for The Writer’s Table. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

#ShortStorySeptember: Stories by Katherine Heiny, Shena Mackay and Ian McEwan

Every September I enjoy focusing on short stories, which I seem to read at a rate of only one or two collections per month in the rest of a year. This year, Lisa of ANZ Lit Lovers is hosting Short Story September as a blogger challenge for the first time. She’s encouraging people to choose individual short stories they would recommend, so I’ll be centring all of my reviews around one particular story but also giving my reaction to the collections as a whole.

“Dark Matter”

from

Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny (2015)

“One week in late February, Rhodes and Gildas-Joseph told Maya the same come fact, that there was a movement to reinstate Plato’s status as a planet.”

Maya is engaged to Rhodes but also sleeping with Gildas-Joseph, the director of the university library where she works. She’s one of Heiny’s typical whip-smart, exasperated protagonists, irresistibly drawn to a man or two even though they seem like priggish or ridiculous bores (witness the “come fact” above – neither can stop himself from mansplaining after sex). Having an affair means always having to keep your wits about you. Maya bumps into her boss with his wife, Adèle, at a colleague’s cocktail party and in line for the movies, and one day her fiancé’s teenage sister, Magellan (seriously, what is up with these names?!), turns up at the coffee shop where she is supposed to be meeting Gildas-Joseph. Quick, act natural. By the end, Maya knows that she must decide between the two men.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This triptych of linked stories is evidence that Heiny was working her way towards a novel, and I certainly prefer Standard Deviation and Early Morning Riser. However, I really liked Heiny’s 2023 story collection, Games and Rituals, which has much more variety.

I like the second person as much as anyone but three instances of “You” narration is too much. The best of these was “The Rhett Butlers,” about a teenager whose history teacher uses famous character names as aliases when checking them into motels for trysts. The cover image is from this story: “The part of your life that contains him is too sealed off, like the last slice of cake under one of those glass domes.”

Although all of these stories are entertaining and have some of the insouciance and bittersweetness of Nora Ephron’s Heartburn, they are so overwhelmingly about adultery (the main theme of at least 8 of 11) that they feel one-note.

why have an affair if not to say bad things about your spouse?

She thought that was the essence of motherhood: acting like you knew what you were talking about when you didn’t. That, and looking at people’s rashes. It was probably why people had affairs.

I would recommend any of Heiny’s other books over this one, but I wanted to read everything she’s published and I wouldn’t say my time spent on this was a waste. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

“All the Pubs in Soho”

from

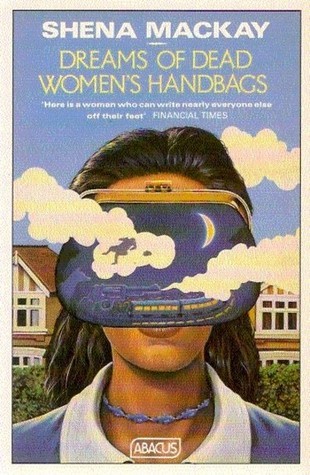

Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay (1987)

“It was his father’s vituperation about ‘those bloody pansies at Old Hollow’ that had brought Joe to the cottage on this empty summer holiday afternoon.”

It’s 1956 in Kent and Joe is only eight years old, so it’s not too surprising that, ignorant of the slang, he shows up at Arthur and Guido’s expecting to find flowers dripping red. Their place becomes his haven from a home full of crying, excreting younger siblings and a conventional father who intends to send him to a private girls’ school in the autumn. That’s right, “Joe” is Josephine, who likes to wear boys’ clothes and insists on a male name. Mackay struck me as ahead of her time (rather like Rose Tremain with Sacred Country) in honouring Joe’s chosen pronouns and letting him imagine an adult future in which he’d keep company with Arthur and Guido’s bohemian, artistic set – the former is a poet, the latter a painter – and they’d take him round ‘all the pubs in Soho.’ But in a sheltered small town where everyone has a slur ready for the men, it is not to be. Things don’t end well, but thankfully not as badly as I was hoping, and Joe has plucked up the courage to resist his father. There’s all the emotional depth and character development of a novella in this 26-page story.

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne. In “Violets and Strawberries in the Snow,” a man in a mental institution awaits a holiday visit from his daughters. “What do we do now?” he asks a fellow inmate. “We could hang ourselves in the tinsel” is the reply. It’s very black comedy indeed. The same is true of a Halloween-set story that I’ll revisit next month.

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne. In “Violets and Strawberries in the Snow,” a man in a mental institution awaits a holiday visit from his daughters. “What do we do now?” he asks a fellow inmate. “We could hang ourselves in the tinsel” is the reply. It’s very black comedy indeed. The same is true of a Halloween-set story that I’ll revisit next month.

The cover is so bad it’s good, amirite? In the title story, Susan Vigo is on her way by train to give a speech at a writers’ workshop and running through possible plots for her mystery novel in progress. “Slaves to the Mushroom” is another great one that takes place on a mushroom farm. Mackay’s settings are often surprising, her vocabulary precise, and her portraits of young people as cutting as those of the aged are pitiful. This would serve as a great introduction to her style. (Secondhand – Slightly Foxed Books, Berwick) ![]()

“The Grown-up”

from

The Daydreamer by Ian McEwan (1994)

“The following morning Peter Fortune woke from troubled dreams to find himself transformed into a giant person, an adult.”

A much better Kafka homage, this, than that forgettable novella The Cockroach that McEwan published in 2019. Every story of this linked collection features Peter, a 10-year-old with a very active imagination. Three of the stories are straightforward body-swap narratives (with his sister’s mangled doll, his cat, or his baby cousin), whereas in this one he’s not trading with anyone else but still experiencing what it’s like to be someone else. In this case, a young man falling in love for the first time. Just the previous day, at the family’s holiday cottage in Cornwall, he’d been bemoaning how boring adults are: all they want to do is sit on the beach and chat or read, when there’s so much world out there to explore and turn into a personal playground. He never wants to be one of them. Now he realizes there are different ways to enjoy life; “he stopped and turned to look at the grown-ups one more time. … He felt differently about them now. There were things they knew and liked which for him were only just appearing, like shapes in a mist. There were adventures ahead of him after all.”

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s To Be a Cat. At the time, I’d not heard of this and couldn’t believe McEwan had written something suitable for kids! These stories were ones he read aloud to his children as he composed them. There is a hint of gruesomeness in “The Dolls,” but most are just playful. “Vanishing Cream” is a cautionary tale about wanting your family to go away. In “The Bully,” Peter turns a bully into a tentative friend. “The Baby” sees him changing his mind about an annoying relative, while “The Burglar” has him imagining himself a hero who stops the spate of neighbourhood break-ins. Events are explained away as literal dreams, daydreams or a bit of magic. This was an offbeat gem. Try it for a very different taste of McEwan! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s To Be a Cat. At the time, I’d not heard of this and couldn’t believe McEwan had written something suitable for kids! These stories were ones he read aloud to his children as he composed them. There is a hint of gruesomeness in “The Dolls,” but most are just playful. “Vanishing Cream” is a cautionary tale about wanting your family to go away. In “The Bully,” Peter turns a bully into a tentative friend. “The Baby” sees him changing his mind about an annoying relative, while “The Burglar” has him imagining himself a hero who stops the spate of neighbourhood break-ins. Events are explained away as literal dreams, daydreams or a bit of magic. This was an offbeat gem. Try it for a very different taste of McEwan! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

#NovNov24 Catch-Up, I: Comyns, Figes, McEwan, Radcliffe, Thériault

Still more to finish reading and/or belatedly review this week before the Novellas in November link-up closes – another, er, nine books after this, I think! I’ll save the short nonfiction for a couple of other posts. For now I have five novellas that range from black comedy to utter heartbreak and from quotidian detail to magic realism.

The House of Dolls by Barbara Comyns (1989)

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead) is typically dark, but the wit counteracts the morbid nature. It reminded me of Beryl Bainbridge, late Barbara Pym, Lore Segal, and Muriel Spark. (Passed on by Liz – thank you! Even with the hideous cover.) [156 pages]

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead) is typically dark, but the wit counteracts the morbid nature. It reminded me of Beryl Bainbridge, late Barbara Pym, Lore Segal, and Muriel Spark. (Passed on by Liz – thank you! Even with the hideous cover.) [156 pages] ![]()

Light by Eva Figes (1983)

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages] ![]()

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan (2007)

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages] ![]()

The Old Haunts by Allan Radcliffe (2023)

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages] ![]()

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy for review.

The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman by Denis Thériault (2005; 2008)

[Translated from the French by Liedewy Hawke]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages] ![]()

Which of these catches your eye?

Book Serendipity, April to May 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. Of course, the truer term would be synchronicity, but the branding has stuck. In Liz Jensen’s Your Wild and Precious Life, she mentions that Carl Jung coined the term “synchronicity” for what he described as “a meaningful coincidence of two or more events where something other than the probability of chance is involved.” I like thinking that it’s not just a matter of luck.

This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. I would normally have waited until the end of June, but I had way too many coincidences stored up! Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to finding them. People frequently ask how I remember all of these incidents. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Reading two King Lear updates at the same time: Private Rites by Julia Armfield and Daughter by Claudia Dey. The former has been specifically marketed as a “lesbian Lear,” but I had no idea that the latter also features two sisters plus a younger half-sister and their interactions with a larger-than-life father.

- Eating beans straight out of the tin in The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

- Dead mice in Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood.

- Cloth holding the jaw of a corpse closed in one story from Barcelona by Mary Costello and A Woman’s Story by Annie Ernaux.

- Others see a character’s wife as a whore but the husband is oblivious in The Shipping News by E. Annie Proulx and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

- Main character called Mona in Daughter by Claudia Dey and Mona of the Manor by Armistead Maupin.

- Being surprised at an older man still having his natural hair colour in one story of Barcelona by Mary Costello (where he’s aged 76) and Life in the Balance by Jim Down (where it’s Alan Bennett, at 84!).

- A character named Anjali in Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan and Moral Injuries by Christie Watson.

- A character named Cherry in Daughter by Claudia Dey and one story of This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things by Naomi Wood.

- My second memoir in two months in which a twentysomething son dies suddenly of a presumed heart problem: Fi by Alexandra Fuller, followed by Your Wild and Precious Life by Liz Jensen. (And a third in which his young friend died in the same way: The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater.) Also, Fuller and Jensen both see signs of their sons’ continued presence in bird sightings.

- Scratches on the inside of a coffin as proof of being buried alive in one story of Barcelona by Mary Costello and Life in the Balance by Jim Down.

- Surprise that one didn’t know the exact moment that a loved one died in one story of Barcelona by Mary Costello and Your Wild and Precious Life by Liz Jensen.

- Discussion of the meaning of brain stem death and a mention of meningococcal sepsis in Life in the Balance by Jim Down and Moral Injuries by Christie Watson.

- A scene set in a Denny’s diner in The Whole Staggering Mystery by Sylvia Brownrigg and After Dark by Haruki Murakami.

- A description of halal butchery in Barcelona by Mary Costello and Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad.

- A mention of ballet choreographer George Balanchine in Dances by Nicole Cuffy and The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater.

- A woman has an affair with a female postal worker in Mona of the Manor by Armistead Maupin and The Shipping News by Annie Proulx, both of which I DNFed.

- A character named Magdalena in Cloistered by Catherine Coldstream and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz. The latter goes by Lena, which is also the name of the main character in Jungle House by Julianne Pachico. And there’s a character named Lina in Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad.

- Being presented with powdered milk in Cloistered by Catherine Coldstream and Whale Fall by Elizabeth O’Connor.

- First I read a novel about a convent plagued by mice (Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood). Then I read a memoir about a convent plagued by feral cats (Cloistered by Catherine Coldstream).

- Buffalo, New York as a setting in Consent by Jill Ciment and The Age of Loneliness by Laura Marris. It’s also mentioned in Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad.

- Watching pigeons on one’s balcony in Keep by Jenny Haysom, Your Wild and Precious Life by Liz Jensen, and The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

- The mother is named Gloria in Consent by Jill Ciment and Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (and The War for Gloria by Atticus Lish, a DNF).

- A character named Anton in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Jungle House by Julianne Pachico.

- A cat named Dog in The Door-to-Door Bookstore by Carsten Henn and a dog named Tiger in Jungle House by Julianne Pachico.

- Two nature books that feature wild cold-water swimming (though don’t they all these days?!): In All Weathers by Matt Gaw and Your Wild and Precious Life by Liz Jensen.

- Two nature books that mention W.H. Hudson: In All Weathers by Matt Gaw and North with the Spring by Edwin Way Teale.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

- A mention of Poughkeepsie, New York in Birdeye by Judith Heneghan and Woman of Interest by Tracy O’Neill.

- A 1950s scene of perusing a lipstick display in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym.

- A woman with a broken leg worries about how her garden will fare in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- The same silent film image of a spaceship entering the moon’s eye (from Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon) appears in Knife by Salman Rushdie and The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick. (I think this is the uncanniest coincidence of all this time!)

- A cleric who wears a biretta in Excellent Women by Barbara Pym and Daughters of the House by Michèle Roberts.

- A Black single mother who believes in the power of crystals in Company by Shannon Sanders and Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace.

- An older woman really doesn’t want to leave her home but is moving into a retirement facility in Keep by Jenny Haysom and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt. (There’s also a young woman who refuses to leave her house in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown.)

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

- A mother writing a bad check becomes an important plot point in Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt and Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

- The Yiddish word feh (an expression of disappointment) appears in Feh by Shalom Auslander (no surprise there!) but also in A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg, both of which are pre-release books I am reading for Shelf Awareness reviews.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Reading with the Seasons: Summer 2021, Part I

I’m more likely to choose lighter reads and dip into genre fiction in the summer than at other times of year. The past few weeks have felt more like autumn here in southern England, but summer doesn’t officially end until September 22nd. So, if I get a chance (there’s always a vague danger to labelling something “Part I”!), before then I’ll follow up with another batch of summery reads I have on the go: Goshawk Summer, Klara and the Sun, Among the Summer Snows, A Shower of Summer Days, and a few summer-into-autumn children’s books.

For this installment I have a quaint picture book, a mystery, a travel book featured for its title, and a very English classic. I’ve chosen a representative quote from each.

Summer Story by Jill Barklem (1980)

One of a quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories in small hardbacks. It wouldn’t be summer without weddings, and here one takes place between two mice, Poppy Eyebright and Dusty Dogwood (who work in the dairy and the flour mill, respectively), on Midsummer’s Day. I loved the little details about the mice preparing their outfits and the wedding feast: “Cool summer foods were being made. There was cold watercress soup, fresh dandelion salad, honey creams, syllabubs and meringues.” We’re given cutaway views of various tree stumps, like dollhouses, and the industrious activity going on within them. Like any wedding, this one has its mishaps, but all is ultimately well, like in a classical comedy. This reminded me of the Church Mice books or Beatrix Potter’s works: very sweet, quaint and English.

One of a quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories in small hardbacks. It wouldn’t be summer without weddings, and here one takes place between two mice, Poppy Eyebright and Dusty Dogwood (who work in the dairy and the flour mill, respectively), on Midsummer’s Day. I loved the little details about the mice preparing their outfits and the wedding feast: “Cool summer foods were being made. There was cold watercress soup, fresh dandelion salad, honey creams, syllabubs and meringues.” We’re given cutaway views of various tree stumps, like dollhouses, and the industrious activity going on within them. Like any wedding, this one has its mishaps, but all is ultimately well, like in a classical comedy. This reminded me of the Church Mice books or Beatrix Potter’s works: very sweet, quaint and English.

Source: Public library

My rating:

These next two give a real sense of how heat affects people, physically and emotionally.

Heatstroke by Hazel Barkworth (2020)

“In the heat, just having a human body was a chore. Just keeping it suitable for public approval was a job”

From the first word (“Languid”) on, this novel drips with hot summer atmosphere, with its opposing connotations of discomfort and sweaty sexuality. Rachel is a teacher of adolescents as well as the mother of a 15-year-old, Mia. When Lily, a pupil who also happens to be one of Mia’s best friends, goes missing, Rachel is put in a tough spot. I mostly noted how Barkworth chose to construct the plot, especially when to reveal what. By the one-quarter point, Rachel works out what’s happened to Lily; by halfway, we know why Rachel isn’t telling the police everything.

From the first word (“Languid”) on, this novel drips with hot summer atmosphere, with its opposing connotations of discomfort and sweaty sexuality. Rachel is a teacher of adolescents as well as the mother of a 15-year-old, Mia. When Lily, a pupil who also happens to be one of Mia’s best friends, goes missing, Rachel is put in a tough spot. I mostly noted how Barkworth chose to construct the plot, especially when to reveal what. By the one-quarter point, Rachel works out what’s happened to Lily; by halfway, we know why Rachel isn’t telling the police everything.

The dynamic between Rachel and Mia as they decide whether to divulge what they know is interesting. This is not the missing person mystery it at first appears to be, and I didn’t sense enough literary quality to keep me wanting to know what would happen next. I ended up skimming the last third. It would be suitable for readers of Rosamund Lupton, but novels about teenage consent are a dime a dozen these days and this paled in comparison to My Dark Vanessa. For a better sun-drenched novel, I recommend A Crime in the Neighborhood.

Source: Public library

My rating:

The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life by Ryszard Kapuściński (1998; 2001)

[Translated from the Polish by Klara Glowczewska]

“Dawn and dusk—these are the most pleasant hours in Africa. The sun is either not yet scorching, or it is no longer so—it lets you be, lets you live.”

The Polish Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This collection of essays spans decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états. Living among Africans rather than removed in a white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I read the first half last year and then picked the book back up again to finish this year. The last piece, “In the Shade of a Tree, in Africa” especially stood out. In murderously hot conditions, shade and water are two essentials. A large mango tree serves as an epicenter of activities: schooling, conversation, resting the herds, and so on. I appreciated how Kapuściński never resorts to stereotypes or flattens differences: “Africa is a thousand situations, varied, distinct, even contradictory … everything depends on where and when.”

The Polish Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This collection of essays spans decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états. Living among Africans rather than removed in a white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I read the first half last year and then picked the book back up again to finish this year. The last piece, “In the Shade of a Tree, in Africa” especially stood out. In murderously hot conditions, shade and water are two essentials. A large mango tree serves as an epicenter of activities: schooling, conversation, resting the herds, and so on. I appreciated how Kapuściński never resorts to stereotypes or flattens differences: “Africa is a thousand situations, varied, distinct, even contradictory … everything depends on where and when.”

Along with Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts and the Jan Morris anthology A Writer’s World, this is one of the best few travel books I’ve ever read.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

August Folly by Angela Thirkell (1936)

“The sun was benignantly hot, the newly mown grass smelt sweet, bees were humming in a stupefying way, Gunnar was purring beside him, and Richard could hardly keep awake.”

I’d been curious to try Thirkell, and this fourth Barsetshire novel seemed as good a place to start as any. Richard Tebben, not the best and brightest that Oxford has to offer, is back in his parents’ village of Worsted for the summer and dreading the boredom to come. That is, until he meets beautiful Rachel Dean and is smitten – even though she’s mother to a brood of nine, most of them here with her for the holidays. He sets out to impress her by offering their donkey, Modestine, for rides for the children, and rather accidentally saving her daughter from a raging bull. Meanwhile, Richard’s sister Margaret can’t decide if she likes being wooed, and the villagers are trying to avoid being roped into Mrs Palmer’s performance of a Greek play. The dialogue can be laughably absurd. There are also a few bizarre passages that seem to come out nowhere: when no humans are around, the cat and the donkey converse.

I’d been curious to try Thirkell, and this fourth Barsetshire novel seemed as good a place to start as any. Richard Tebben, not the best and brightest that Oxford has to offer, is back in his parents’ village of Worsted for the summer and dreading the boredom to come. That is, until he meets beautiful Rachel Dean and is smitten – even though she’s mother to a brood of nine, most of them here with her for the holidays. He sets out to impress her by offering their donkey, Modestine, for rides for the children, and rather accidentally saving her daughter from a raging bull. Meanwhile, Richard’s sister Margaret can’t decide if she likes being wooed, and the villagers are trying to avoid being roped into Mrs Palmer’s performance of a Greek play. The dialogue can be laughably absurd. There are also a few bizarre passages that seem to come out nowhere: when no humans are around, the cat and the donkey converse.

This was enjoyable enough, in the same vein as books I’ve read by Barbara Pym, Miss Read, and P.G. Wodehouse, though I don’t expect I’ll pick up more by Thirkell. (No judgment intended on anyone who enjoys these authors. I got so much flak and fansplaining when I gave Pym and Wodehouse 3 stars and dared to call them fluffy or forgettable, respectively! There are times when a lighter read is just what you want, and these would also serve as quintessential English books revealing a particular era and class.)

Source: Public library

My rating:

As a bonus, I have a book about how climate change is altering familiar signs of the seasons.

Forecast: A Diary of the Lost Seasons by Joe Shute (2021)

“So many records are these days being broken that perhaps it is time to rewrite the record books, and accept the aberration has become the norm.”

Shute writes a weather column for the Telegraph, and in recent years has reported on alarming fires and flooding. He probes how the seasons are bound up with memories, conceding the danger of giving in to nostalgia for a gloried past that may never have existed. However, he provides hard evidence in the form of long-term observations (phenology) such as temperature data and photo archives that reveal that natural events like leaf fall and bud break are now occurring weeks later/earlier than they used to. He also meets farmers, hunts for cuckoos and wildflowers, and recalls journalistic assignments.

Shute writes a weather column for the Telegraph, and in recent years has reported on alarming fires and flooding. He probes how the seasons are bound up with memories, conceding the danger of giving in to nostalgia for a gloried past that may never have existed. However, he provides hard evidence in the form of long-term observations (phenology) such as temperature data and photo archives that reveal that natural events like leaf fall and bud break are now occurring weeks later/earlier than they used to. He also meets farmers, hunts for cuckoos and wildflowers, and recalls journalistic assignments.

The book deftly recreates its many scenes and conversations, and inserts statistics naturally. It also delicately weaves in a storyline about infertility: he and his wife long for a child and have tried for years to conceive, but just as the seasons are out of kilter, there seems to be something off with their bodies such that something that comes so easily for others will not for them. A male perspective on infertility is rare – I can only remember encountering it before in Native by Patrick Laurie – and these passages are really touching. The tone is of a piece with the rest of the book: thoughtful and gently melancholy, but never hopeless (alas, I found The Eternal Season by Stephen Rutt, on a rather similar topic, depressing).

Forecast is wide-ranging and so relevant – the topics it covers kept coming up and I would say to my husband, “oh yes, that’s in Joe Shute’s book.” (For example, he writes about the Ladybird What to Look For series and then we happened on an exhibit of the artwork at Mottisfont Abbey.) I can see how some might say it crams in too much or veers too much between threads, but I thought Shute handled his material admirably.

Source: Public library

My rating:

Have you been reading anything particularly fitting for summer this year?

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore (1955)

The readalong that Cathy of 746 Books is hosting for Brian Moore’s centenary was just the excuse I needed to try his work for the first time. My library had a copy of The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, his most famous work and the first to be published under his own name (after some pseudonymous potboilers), so that’s where I started.

Judith Hearne is a pious, set-in-her-ways spinster in Belfast. As the story opens, the piano teacher is moving into a new boarding house and putting up the two portraits that watch over her: a photo of her late aunt, whom Judith cared for in her sunset years; and the Sacred Heart. This establishment is run by a nosy landlady, Mrs. Henry Rice, and her adult son Bernard, who is writing his poetic magnum opus and carrying on with the maid. Recently joining the household is James Madden, the landlady’s brother, who is back from 30 years in New York City. Disappointed in his career and in his adult daughter, he’s here to start over.

Moore’s third-person narration slips easily between the viewpoints of multiple characters, creating a dramatic irony between their sense of themselves and what others think of them. Initially, we spend the most time in Judith’s head – an uncomfortable place to be because of how simultaneously insecure and hypercritical she is. She’s terrified of rejection, which she has come to expect, but at the same time she has nasty, snobbish thoughts about her fellow lodgers, especially overweight Bernard. The dynamic is reversed on her Sunday afternoons with the O’Neills, who, peering through the curtains as she arrives, groan at their onerous duty of entertaining a dull visitor who always says the same things and gets tipsy on sherry.

An unfortunate misunderstanding soon arises between Judith and James: in no time she’s imagining romantic scenarios, whereas he, wrongly suspecting she has money stashed away, hopes she can be lured into investing in his planned American-style diner in Dublin. “A pity she looks like that,” he thinks. Later we get a more detailed description of Judith from a bank cashier: “On the wrong side of forty with a face as plain as a plank, and all dressed up, if you please, in a red raincoat, a red hat with a couple of terrible-looking old wax flowers in it.”

An unfortunate misunderstanding soon arises between Judith and James: in no time she’s imagining romantic scenarios, whereas he, wrongly suspecting she has money stashed away, hopes she can be lured into investing in his planned American-style diner in Dublin. “A pity she looks like that,” he thinks. Later we get a more detailed description of Judith from a bank cashier: “On the wrong side of forty with a face as plain as a plank, and all dressed up, if you please, in a red raincoat, a red hat with a couple of terrible-looking old wax flowers in it.”

Oh how the heart aches for this figure of pathos. James’s situation, what with the ultimate failure of his American dream, echoes hers in several ways. Something happens that lessens our sympathy for James, but Judith remains a symbol of isolation and collapse. The title also reflects the spiritual aspect of this breakdown: Judith feels that she’s walking a lonely road, like Jesus did on the way to the crucifixion, and the Catholic Church to which she’s devoted, far from being a support in time of despair, is only the source of more judgment.

Alcoholism, mental illness, and religious doubt swirl together to make for a truly grim picture of life on the margins. The novel also depicts casual racism and a scene of sexual assault. No bed of roses here. But Moore’s writing, unflinching yet compassionate, renders each voice and perspective distinct in an unforgettable character study full of intense scenes. I especially loved how the final scene returns full circle. I’d particularly recommend this to readers of Tove Ditlevsen, Muriel Spark and Elizabeth Taylor, and fans of Barbara Pym’s Quartet in Autumn. I’ll definitely try more from Moore – I found a copy of The Colour of Blood in a Little Free Library in Somerset, so will add that to my stack for 20 Books of Summer.

My rating:

The “P.S.” section of the Harper Perennial paperback I borrowed from the library contains a lot of interesting information on Moore’s life and the composition of Judith Hearne. After time as a civilian worker in the British army, Moore moved to Canada and became a journalist. Later he would move to Malibu and write the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain.

The protagonist was based on a woman Moore’s parents invited over for Sunday diners in Belfast. Like Judith, she loved wearing red and went on about the aunt who raised her. Moore said, “When I wrote Judith Hearne I was very lonely, writing in a rented caravan, I had almost no friends, I’d given up my beliefs, was earning almost no money as a reporter and I didn’t see much of a future. So I could identify with a dipsomaniac, isolated spinster.” The novel was rejected by 12 publishing houses before the firm André Deutsch, namely reader Laurie Lee and co-director Diana Athill, recognized its genius and accepted it for publication.

Book Serendipity, 2019 Second Half

I call it serendipitous when two or more books that I’m reading at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once – usually between 10 and 20 – I guess I’m more prone to such incidents. I post these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. What’s the weirdest one you’ve had lately? (The following are in rough chronological order.)

[Previous 2019 Book Serendipity posts from April and July.]

- Two novels in which a character attempts to glimpse famous mountains out of a train window but it’s so rainy they can barely be seen: The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma and The Pine Islands by Marion Poschmann.

- Ex-husbands move from England to California and remarry younger women in The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam and Heat Wave by Penelope Lively.

References to Edgar Allan Poe in both Timbuktu by Paul Auster and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma.

References to Edgar Allan Poe in both Timbuktu by Paul Auster and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma.

- An account of Percy Shelley’s funeral pyre in both The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma and Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson.

- Mentions of barn owls being killed by eating poisoned rats in Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington and Homesick by Catrina Davies.

- Miriam Rothschild is mentioned in Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman and An Obsession with Butterflies by Sharman Apt Russell.

- Gorse is thrown on bonfires in Homesick by Catrina Davies and The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam.

A character has a nice cup of Ovaltine in Some Tame Gazelle by Barbara Pym and The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam.

A character has a nice cup of Ovaltine in Some Tame Gazelle by Barbara Pym and The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam.

- I started two books with “Bloom” in the title on the same day.

Two books I finished about the same time conclude by quoting or referring to the T. S. Eliot lines about coming back to the place where you started and knowing it for the first time (Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington and This Is Not a Drill, the Extinction Rebellion handbook).

Two books I finished about the same time conclude by quoting or referring to the T. S. Eliot lines about coming back to the place where you started and knowing it for the first time (Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington and This Is Not a Drill, the Extinction Rebellion handbook).

- Three books in which the narrator wonders whether to tell the truth slant (quoting Emily Dickinson, consciously or not): The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma, The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver and The Hiding Game by Naomi Wood.

- On the same day, I saw mentions of crullers in both On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming and The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

- There are descriptions of starling murmurations over Brighton Pier in both Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman and Expectation by Anna Hope. (Always brings this wonderful Bell X1 song to mind!)

- I was reading The Outermost House by Henry Beston and soon after found an excerpt from it in Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman; later I started The Easternmost House by Juliet Blaxland, whose title is a deliberate tip of the hat to Beston.

At a fertility clinic, the author describes a pair of transferred embryos as “two sequins of light” (in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming) and “two points of light” (in Expectation by Anna Hope).

At a fertility clinic, the author describes a pair of transferred embryos as “two sequins of light” (in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming) and “two points of light” (in Expectation by Anna Hope).

- Mentions of azolla ferns in Time Song by Julia Blackburn and Bloom (aka Slime) by Ruth Kassinger.

Incorporation of a mother’s brief memoir in the author’s own memoir in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming and All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay.

Incorporation of a mother’s brief memoir in the author’s own memoir in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming and All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay.

- Artist mothers in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming, All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay, and Expectation by Anna Hope.

- Missionary fathers in The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver and The Wind that Lays Waste by Selva Almada.

- Twins, one who’s disabled from a birth defect and doesn’t speak much, in Golden Child by Claire Adam and The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver.

An Irish-American family in a major East Coast city where the teenage boy does construction work during the summers in Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane and The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

An Irish-American family in a major East Coast city where the teenage boy does construction work during the summers in Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane and The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

- SPOILERS: A woman with terminal cancer refuses treatment so she can die on her own terms and is carried out into her garden in Expectation by Anna Hope and A Reckoning by May Sarton.

- A 27-year-old professor has a student tearfully confide in her in Crow Lake by Mary Lawson and The Small Room by May Sarton.

- Reading The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom at the same time as The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

“I was nineteen years old and an idiot” (City of Girls, Elizabeth Gilbert); “I was fifteen and generally an idiot” (The Dutch House, Ann Patchett).

“I was nineteen years old and an idiot” (City of Girls, Elizabeth Gilbert); “I was fifteen and generally an idiot” (The Dutch House, Ann Patchett).

- Mentions of a conjuring tricks book in Time Song by Julia Blackburn and Fifth Business by Robertson Davies.

- A teen fleeces their place of employment in Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls and Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? by Lorrie Moore.

- A talking parrot with a religious owner in The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver and Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout.

- Pictorial book serendipity: three books I was reading, and another waiting in the wings, had a red, black and white color scheme.

Kripalu (a Massachusetts retreat center) is mentioned in Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene.

Kripalu (a Massachusetts retreat center) is mentioned in Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene.

- The character of Netty Quelch in Robertson Davies’s The Manticore reminds me of Fluffy in Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House.

- The artist Chardin is mentioned in How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain de Botton and Varying Degrees of Hopelessness by Lucy Ellmann.

- A Czech grand/father who works in a plant nursery in the opening story of Andrea Barrett’s Ship Fever and Patricia Hampl’s The Florist’s Daughter.

- The author was in Eva Le Gallienne’s NYC theatre company (Madeleine L’Engle’s Two-Part Invention and various works by May Sarton, also including a biography of her).

Gillian Rose’s book Love’s Work is mentioned in both Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth and My Year Off by Robert McCrum. (I will clearly have to read the Rose!)

Gillian Rose’s book Love’s Work is mentioned in both Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth and My Year Off by Robert McCrum. (I will clearly have to read the Rose!)

- Sarah Baartman (displayed in Europe as the “Hottentot Venus”) is mentioned in Shame on Me by Tessa McWatt and Hull by Xandria Phillips.

Women in Translation Month 2019, Part II: Almada and Fenollera

All Spanish-language choices this time: an Argentinian novella, a Spanish novel, and a couple of Chilean short stories to whet your appetite for a November release.

The Wind that Lays Waste by Selva Almada (2012; English translation, 2019)

[Translated by Chris Andrews]

Selva Almada’s debut novella is also her first work to appear in English. Though you might swear this is set in the American South, it actually takes place in her native Argentina. The circadian narrative pits two pairs of characters against each other. On one hand we have the Reverend Pearson and his daughter Leni, itinerants who are driven ever onward by the pastor’s calling. On the other we have “The Gringo” Brauer, a mechanic, and his assistant, José Emilio, nicknamed “Tapioca.”

Selva Almada’s debut novella is also her first work to appear in English. Though you might swear this is set in the American South, it actually takes place in her native Argentina. The circadian narrative pits two pairs of characters against each other. On one hand we have the Reverend Pearson and his daughter Leni, itinerants who are driven ever onward by the pastor’s calling. On the other we have “The Gringo” Brauer, a mechanic, and his assistant, José Emilio, nicknamed “Tapioca.”

On his way to visit Pastor Zack, Reverend Pearson’s car breaks down. While the Gringo sets to work fixing the vehicle, the preacher tries witnessing to Tapioca. He senses something special in the boy, perhaps even recognizing a younger version of himself, and wants him to have more of a chance in life than he’s currently getting at the garage. As a violent storm comes up, we’re left to wonder how Leni’s cynicism, the Reverend’s zealousness, the Gringo’s suspicion, and Tapioca’s resolve will all play out.

Different as they are, there are parallels to be drawn between these characters, particularly Leni and Tapioca, who were both abandoned by their mothers. I particularly liked the Reverend’s remembered sermons, printed in italics, and Leni’s sarcastic thoughts about her father’s vocation: “They always ended up doing what her father wanted, or, as he saw it, what God expected of them” and “she admired the Reverend deeply but disapproved of almost everything her father did. As if he were two different people.”

The setup and characters are straight out of Flannery O’Connor. The book doesn’t go as dark as I expected; I’m not sure I found the ending believable, even if it was something of a relief.

My rating:

My thanks to Charco Press for the free copy for review. Last year I reviewed two Charco releases: Die, My Love and Fish Soup.

See also Susan’s review.

The Awakening of Miss Prim by Natalia Sanmartin Fenollera (2013; English translation, 2014)

[Translated by Sonia Soto]

San Ireneo de Arnois is a generically European village that feels like it’s been frozen in about 1950: it’s the sort of place that people who are beaten down by busy city life retreat to so they can start creative second careers. Prudencia Prim comes here to interview for a job as a librarian, having read a rather cryptic job advertisement. Her new employer, The Man in the Wingchair (never known by any other name), has her catalogue his priceless collection of rare books, many of them theological treatises in Latin and Greek. She’s intrigued by this intellectual hermit who doesn’t value traditional schooling yet has the highest expectations for the nieces and nephews in his care.

San Ireneo de Arnois is a generically European village that feels like it’s been frozen in about 1950: it’s the sort of place that people who are beaten down by busy city life retreat to so they can start creative second careers. Prudencia Prim comes here to interview for a job as a librarian, having read a rather cryptic job advertisement. Her new employer, The Man in the Wingchair (never known by any other name), has her catalogue his priceless collection of rare books, many of them theological treatises in Latin and Greek. She’s intrigued by this intellectual hermit who doesn’t value traditional schooling yet has the highest expectations for the nieces and nephews in his care.

In the village at large, she falls in with a group of women who have similarly ridiculous names like Hortensia and Herminia and call themselves feminists yet make their first task the finding of a husband for Prudencia. All of this is undertaken with the aid of endless cups of tea or hot chocolate and copious sweets. The village and its doings are, frankly, rather saccharine. No prizes for guessing who ends up being Prudencia’s chief romantic interest despite their ideological differences; you’ll guess it long before she admits it to herself at the two-thirds point.

As much as this tries to be an intellectual fable for bibliophiles (Prudencia insists that The Man in the Wingchair give Little Women to his niece to read, having first tried it himself despite his snobbery), it’s really just a thinly veiled Pride and Prejudice knock-off – and even goes strangely Christian-fiction in its last few pages. If you enjoyed The Readers of Broken Wheel Recommend and have a higher tolerance for romance and chick lit than I, you may well like this. It’s pleasantly written in an old-fashioned Pym-homage style, but ultimately it goes on my “twee” shelf and will probably return to a charity shop, from whence it came.

My rating:

Humiliation by Paulina Flores (2016; English translation, 2019)

[Translated by Megan McDowell]

I’ve read the first two stories so far, “Humiliation” and “Teresa,” which feature young fathers and turn on a moment of surprise. An unemployed father takes his two daughters along to his audition; a college student goes home with a single father for a one-night stand. In both cases, what happens next is in no way what you’re expecting. These are sharp and readable, and I look forward to making my way through the rest over the next month or two.

My rating:

Humiliation will be published by Oneworld on November 7th. My thanks to Margot Weale for a proof copy. I will publish a full review closer to the time.

Did you do any special reading for Women in Translation month this year?

20 Books of Summer, #11–13: Harrison, Pym, Russell

It’s cats and butterflies in the spotlight this time, adding in a gazelle as a metaphor for Freddie Mercury’s somebody to love.

Travelling Cat: A Journey round Britain with Pugwash by Frederick Harrison (1988)

If Tom Cox had been born 20 years earlier, this is the sort of book he might have written. In 1987, saddened more by his cat Podey being run over than by the end of his marriage, Harrison set out from South London in his Ford Transit van for a seven-month drive around the country. He decided to take Pugwash, one of his local (presumably ownerless) cats, along as a companion.

They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well.

They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well.

It’s all a bit silly and dated and lightweight, but enjoyable nonetheless. Plus there are tons of black-and-white photos of “Pugs” and other feline friends. This was a secondhand purchase from The Bookshop, Wigtown.

Favorite lines:

“Cats hate to make prats of themselves. But then, don’t we all?”

(last lines) “Warm, fed, contented, unemployable, and entirely at peace with the world. Yes indeed. Cats certainly know something we don’t.”

Some Tame Gazelle by Barbara Pym (1950)

(An example of a book that just happens to have an animal in the title.) I’d only read one other Pym novel, Quartet in Autumn, a late and fairly melancholy story of four lonely older people. With her first novel I’m in more typical territory, I take it. The middle-aged Bede sisters are pillars of the church in their English village. Harriet takes each new curate under her wing, making of them a sort of collection, and fends off frequent marriage proposals from the likes of a celebrity librarian and an Italian count.

Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community.

Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community.

There were a handful of moments that made me laugh, like when the seamstress finds a caterpillar in her cauliflower cheese and has to wipe with a Church Times newspaper when the Bedes run out of toilet paper (such mild sacrilege!). This is enjoyable, if fluffy; it was probably a mistake to have read one of Pym’s more serious books first: I expected too much of this one. If you’re looking for a quick, gentle and escapist read in which nothing awful will happen, though, it would make a good choice. Knowing most of her books are of a piece, I wouldn’t read more than one of the remainder – it’ll most likely be Excellent Women.

An Obsession with Butterflies: Our Long Love Affair with a Singular Insect by Sharman Apt Russell (2003)

This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing?

This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing?

The final third of the book was strongest for me, including a trip to London’s Natural History Museum; another to Costa Rica’s butterfly ranches, an example of successful ecotourism; and a nicely done case study of the El Segundo Blue butterfly, which was brought back from the brink of extinction by restoration of its southern California dunes habitat. Russell, a New Mexico-based author of novels and nonfiction, also writes about butterflies’ cultural importance: “No matter our religious beliefs, we accept the miracle of metamorphosis. One thing becomes another. … Butterflies wake us up.”

I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.

I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.

(I’ve put the book aside for now but will go back to it in September as I focus on short stories.)

Other butterfly-themed books I have reviewed:

- Four Wings and a Prayer: Caught in the Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly by Sue Halpern (one of last year’s 20 Books of Summer)

- Ruins by Peter Kuper (a graphic novel set in Mexico, this also picks up on monarch migration)

- Magdalena Mountain by Robert Michael Pyle (a novel about butterfly researchers in Colorado)

Two “Summer” Books

With summer winding down, I decided it was time to read a couple of books with the word in the title to try to keep the season alive. These turned out to be charming, low-key English novels that I would recommend to fans of costume dramas. Both:

I knew very little about Jonathan Smith’s Summer in February when I picked it up in a charity shop. From the ads for the 2013 film adaptation with Dan Stevens, I had in mind that this was an obscure classic. It was actually published in 1995, but is inspired by real incidents spanning 1909 to 1949. It’s set among a group of Royal Academy-caliber artists in Lamorna, Cornwall, including Alfred Munnings, who went on to become the academy’s president.

The crisis comes when Munnings and Captain Gilbert Evans, a local land manager, fall for the same woman. A love triangle might not seem like a very original story idea, but I enjoyed this novel particularly for its Cornish setting (“From dawn to dusk it had rained non-stop, as only Cornwall can”; “The sea was slate grey and the sky streaky bacon”) and for the larger-than-life Munnings, who has a huge store of memorized poetry and is full of outspoken opinions. Two characters describe his contradictions thusly: “I can see he’s crude and loud and unpolished and Joey says he cuts his toenails at picnics but…”; “he’s one in a million, a breath of fresh air, and he’s frank and fearless, which is always a fine thing.” The title refers to the way that love can make any day feel like summer.

The cover image is the painting Morning Ride by A.J. Munnings.

For more information on Munnings, see here.

For more information on Gilbert Evans, see here. (Beware the spoilers!)

From 1961, In a Summer Season was Elizabeth Taylor’s eighth novel. The ensemble cast is led by Kate Heron – newly remarried to Dermot, a man ten years her junior, after the death of her first husband – and made up of her family circle, a few members of the local community, and her best friend Dorothea’s widower and daughter, who return from living abroad about halfway through the book. Set in the London commuter belt, this is full of seemingly minor domestic dilemmas that together will completely overturn staid life before the end.