A Look Back at 2021’s Happenings, Including Recent USA Trip

I’m old-fashioned and still use a desk calendar to keep track of appointments and deadlines. I also add in notes after the fact to remember births, deaths, elections, and other nationally and internationally important events. A look back through my 2021 “The Reading Woman” calendar reminded me that last January held a bit of snow, a third UK lockdown, an attempted coup at the U.S. capitol, and the inauguration of Joe Biden.

Activities continued online for much of the year:

- 15 music gigs (most of them by The Bookshop Band)

- 11 literary events, including book launches and prize announcements

- 9 book club meetings

- 3 literary festivals

- 2 escape rooms

- 1 progressive dinner

We were lucky enough to manage a short break in Somerset and a wonderful week in Northumberland. In August my mother and stepfather came to stay with us for a week and we showed off our area to them on daytrips.

As we entered the autumn, a few more things returned to in-person:

- 5 music gigs

- 2 book club meetings (not counting a few outdoor socials earlier in the year)

- 1 book launch

- 1 conference

I was also fortunate to get back to the States twice this year, once in May–June for my mother’s wedding and again in December for Christmas.

On this most recent trip I had some fun “life meeting books” moments (the photos of me are by Chris Foster):

On this most recent trip I had some fun “life meeting books” moments (the photos of me are by Chris Foster):

- An overnight stay on Chincoteague Island, famous for its semi-wild ponies, prompted me to reread a childhood favorite, Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry.

Driving from my sister’s house to my mother’s new place involves some time on Route 30, aka the Lincoln Highway, through Pennsylvania. Her town even has a tourist attraction called Lincoln Highway Experience that we may check out on a future trip. (The other claims to fame there: it was home to golfer Arnold Palmer and Mister Rogers, and the birthplace of the banana split.)

Driving from my sister’s house to my mother’s new place involves some time on Route 30, aka the Lincoln Highway, through Pennsylvania. Her town even has a tourist attraction called Lincoln Highway Experience that we may check out on a future trip. (The other claims to fame there: it was home to golfer Arnold Palmer and Mister Rogers, and the birthplace of the banana split.)

- At the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, we met the original “Dippy” the diplodocus, a book about whom I reviewed for Foreword in 2020.

- I also took along a copy of The Mysteries of Pittsburgh by Michael Chabon and snapped a photo of it in an appropriately mysterious corner of the museum. Unfortunately, I didn’t get past the first few chapters as this debut novel felt dated and verging on racist.

No matter, though, as I donated it at a Little Free Library.

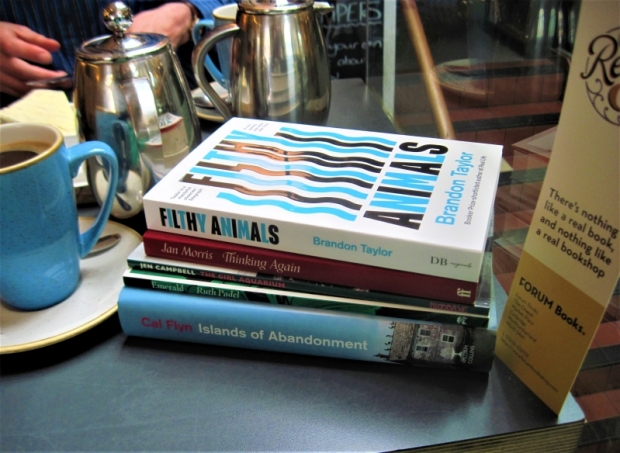

We sought out a few LFLs on our trip, including that one in a log at Cromwell Valley Park in Maryland, where I picked up a Margot Livesey novel and a couple of travel books. My only other acquisition of the trip was a new paperback of Beneficence by Meredith Hall (author of one of the first books to turn me on to memoirs) from Curious Iguana in Frederick, Maryland, my college town. No secondhand book shopping opportunities this time, alas; just lots of driving in our rental car to visit disparate friends and relatives. However, this was my early Christmas book haul from my husband before we set off:

We sought out a few LFLs on our trip, including that one in a log at Cromwell Valley Park in Maryland, where I picked up a Margot Livesey novel and a couple of travel books. My only other acquisition of the trip was a new paperback of Beneficence by Meredith Hall (author of one of the first books to turn me on to memoirs) from Curious Iguana in Frederick, Maryland, my college town. No secondhand book shopping opportunities this time, alas; just lots of driving in our rental car to visit disparate friends and relatives. However, this was my early Christmas book haul from my husband before we set off:

Another fun stop during our trip was at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, where we admired wreaths made of mostly natural ingredients like fruit.

The big news from my household this winter is that we have bought our first home, right around the corner from where we rent now, and hope to move in within the next couple of months. Our aim is to do all the bare-minimum renovations in 2022, in time to put up a tree in the living room bay window and a homemade wreath on the door for next Christmas!

Despite these glimpses of travels and merriment, Covid still feels all too real. I appreciated these reminders I saw recently, one in Bath and the other at the museum in Pittsburgh (Covid Manifesto by Cauleen Smith, which originated on Instagram).

“We all deserve better than ‘back to normal’.”

#NovNov Translated Week: In the Company of Men and Winter Flowers

I’m sneaking in under the wire here with a couple more reviews for the literature in translation week of Novellas in November. These both happen to be translated from the French, and attracted me for their medical themes: the one ponders the Ebola crisis in Africa, and the other presents a soldier who returns from war with disfiguring facial injuries.

In the Company of Men: The Ebola Tales by Véronique Tadjo (2017; 2021)

[Translated from the French by the author and John Cullen; Small Axes Press; 133 pages]

This creative and compassionate work takes on various personae to plot the course of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–16: a doctor, a nurse, a morgue worker, bereaved family members and browbeaten survivors. The suffering is immense, and there are ironic situations that only compound the tragedy: the funeral of a traditional medicine woman became a super-spreader event; those who survive are shunned by their family members. Tadjo flows freely between all the first-person voices, even including non-human narrators such as baobab trees and the fruit bat in which the virus likely originated (then spreading to humans via the consumption of the so-called bush meat). Local legends and songs, along with a few of her own poems, also enter into the text.

This creative and compassionate work takes on various personae to plot the course of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–16: a doctor, a nurse, a morgue worker, bereaved family members and browbeaten survivors. The suffering is immense, and there are ironic situations that only compound the tragedy: the funeral of a traditional medicine woman became a super-spreader event; those who survive are shunned by their family members. Tadjo flows freely between all the first-person voices, even including non-human narrators such as baobab trees and the fruit bat in which the virus likely originated (then spreading to humans via the consumption of the so-called bush meat). Local legends and songs, along with a few of her own poems, also enter into the text.

Like I said about The Appointment, this would make a really interesting play because it is so voice-driven and each character epitomizes a different facet of a collective experience. Of course, I couldn’t help but think of the parallels with Covid – “you have to keep your distance from other people, stay at home, and wash your hands with disinfectant before entering a public space” – none of which could have been in the author’s mind when this was first composed. Let’s hope we’ll soon be able to join in cries similar to “It’s over! It’s over! … Death has brushed past us, but we have survived! Bye-bye, Ebola!” (Secondhand purchase)

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve (2014; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Adriana Hunter; 172 pages]

With Remembrance Day not long past, it’s been the perfect time to read this story of a family reunited at the close of the First World War. Jeanne Caillet makes paper flowers to adorn ladies’ hats – pinpricks of colour to brighten up harsh winters. Since her husband Toussaint left for the war, it’s been her and their daughter Léonie in their little Paris room. Luckily, Jeanne’s best friend Sidonie, an older seamstress, lives just across the hall. When Toussaint returns in October 1918, it isn’t the rapturous homecoming they expected. He’s been in the facial injuries department at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital, and wrote to Jeanne, “I want you not to come.” He wears a white mask over his face, hasn’t regained the power of speech, and isn’t ready for his wife to see his new appearance. Their journey back to each other is at the heart of the novella, the first of Villeneuve’s works to appear in English.

With Remembrance Day not long past, it’s been the perfect time to read this story of a family reunited at the close of the First World War. Jeanne Caillet makes paper flowers to adorn ladies’ hats – pinpricks of colour to brighten up harsh winters. Since her husband Toussaint left for the war, it’s been her and their daughter Léonie in their little Paris room. Luckily, Jeanne’s best friend Sidonie, an older seamstress, lives just across the hall. When Toussaint returns in October 1918, it isn’t the rapturous homecoming they expected. He’s been in the facial injuries department at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital, and wrote to Jeanne, “I want you not to come.” He wears a white mask over his face, hasn’t regained the power of speech, and isn’t ready for his wife to see his new appearance. Their journey back to each other is at the heart of the novella, the first of Villeneuve’s works to appear in English.

I loved the chapters that zero in on Jeanne’s handiwork and on Toussaint’s injury and recovery (Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Butchering Art, is currently writing a book on early plastic surgery; I’ve heard it also plays a major role in Louisa Young’s My Dear, I Wanted to Tell You – both nominated for the Wellcome Book Prize), and the two gorgeous “Word is…” litanies – one pictured below – but found the book as a whole somewhat meandering and quiet. If you’re keen on the time period and have enjoyed novels like Birdsong and The Winter Soldier, it would be a safe bet. (Cathy’s reviewed this one, too.)

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

(In a nice connection with a previous week’s buddy read, Villeneuve’s most recent novel is about Helen Keller’s mother and is called La Belle Lumière (“The Beautiful Light”). I hope it will also be made available in English translation.)

#NonFicNov: Being the Expert on Covid Diaries

This year the Be/Ask/Become the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Veronica of The Thousand Book Project. (In previous years I’ve contributed lists of women’s religious memoirs (twice), accounts of postpartum depression, and books on “care”.)

I’ve been devouring nonfiction responses to COVID-19 for over a year now. Even memoirs that are not specifically structured as diaries take pains to give a sense of what life was like from day to day during the early months of the pandemic, including the fear of infection and the experience of lockdown. Covid is mentioned in lots of new releases these days, fiction or nonfiction, even if just via an introduction or epilogue, but I’ve focused on books where it’s a major element. At the end of the post I list others I’ve read on the theme, but first I feature four recent releases that I was sent for review.

Year of Plagues: A Memoir of 2020 by Fred D’Aguiar

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

Cancer needs a song: tambourine and cymbals and a choir, not to raise it from the dead but [to] lay it to rest finally.

Tracing the effects of his cancer on his wife and children as well as on his own body, he wonders if the treatment will disrupt his sense of his own masculinity. I thought the narrative would hit home given that I have a family member going through the same thing, but it struck me as a jumble, full of repetition and TMI moments. Expecting concision from a poet, I wanted the highlights reel instead of 323 rambling pages.

(Carcanet Press, August 26.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Still, I appreciated Josipovici’s thoughts on literature and his own aims for his work (more so than the rehashing of Covid statistics and official briefings from Boris Johnson et al., almost unbearable to encounter again):

In my writing I have always eschewed visual descriptions, perhaps because I don’t have a strong visual memory myself, but actually it is because reading such descriptions in other people’s novels I am instantly bored and feel it is so much dead wood.

nearly all my books and stories try to force the reader (and, I suppose, as I wrote, to force me) to face the strange phenomenon that everything does indeed pass, and that one day, perhaps sooner than most people think, humanity will pass and, eventually, the universe, but that most of the time we live as though all was permanent, including ourselves. What rich soil for the artist!

Why have I always had such an aversion to first person narratives? I think precisely because of their dishonesty – they start from a falsehood and can never recover. The falsehood that ‘I’ can talk in such detail and so smoothly about what has ‘happened’ to ‘me’, or even, sometimes, what is actually happening as ‘I’ write.

You never know till you’ve plunged in just what it is you really want to write. When I started writing The Inventory I had no idea repetition would play such an important role in it. And so it has been all through, right up to The Cemetery in Barnes. If I was a poet I would no doubt use refrains – I love the way the same thing becomes different the second time round

To write a novel in which nothing happens and yet everything happens: a secret dream of mine ever since I began to write

I did sense some misogyny, though, as it’s generally female writers he singles out for criticism: Iris Murdoch is his prime example of the overuse of adjectives and adverbs, he mentions a “dreadful novel” he’s reading by Elizabeth Bowen, and he describes Jean Rhys and Dorothy Whipple as women “who, raised on a diet of the classic English novel, howled with anguish when life did not, for them, turn out as they felt it should.”

While this was enjoyable to flip through, it’s probably more for existing fans than for readers new to the author’s work, and the Covid connection isn’t integral to the writing experiment.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

A stanza from the below collection to link the first two books to this next one:

Have they found him yet, I wonder,

whoever it is strolling

about as a plague doctor, outlandish

beak and all?

The Crash Wake and Other Poems by Owen Lowery

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

As the seventh anniversary of his wedding to Jayne nears, Lowery reflects on how love has kept him going despite flashbacks to the accident and feeling written off by his doctors. In the second section of the book, the subjects vary from the arts (Paula Rego’s photographs, Stanley Spencer’s paintings, R.S. Thomas’s theology) to sport. There is also a lovely “Remembrance Day Sequence” imagining what various soldiers, including Edward Thomas and his own grandfather, lived through. The final piece is a prose horror story about a magpie. Like a magpie, I found many sparkly gems in this wide-ranging collection.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free e-copy for review.

Behind the Mask: Living Alone in the Epicenter by Kate Walter

[135 pages, so I’m counting this one towards #NovNov, too]

For Walter, a freelance journalist and longtime Manhattan resident, coronavirus turned life upside down. Retired from college teaching and living in Westbeth Artists Housing, she’d relied on activities outside the home for socializing. To a single extrovert, lockdown offered no benefits; she spent holidays alone instead of with her large Irish Catholic family. Even one of the world’s great cities could be a site of boredom and isolation. Still, she gamely moved her hobbies onto Zoom as much as possible, and welcomed an escape to Jersey Shore.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

There’s a lot here to relate to – being glued to the news, anxiety over Trump’s possible re-election, looking forward to vaccination appointments – and the book is also revealing on the special challenges for older people and those who don’t live with family. However, I found the whole fairly repetitive (perhaps as a result of some pieces originally appearing in The Village Sun and then being tweaked and inserted here).

Before an appendix of four short pre-Covid essays, there’s a section of pandemic writing prompts: 12 sets of questions to use to think through the last year and a half and what it’s meant. E.g. “Did living through this extraordinary experience change your outlook on life?” If you’ve been meaning to leave a written record of this time for posterity, this list would be a great place to start.

(Heliotrope Books, November 16.) With thanks to the publicist for the free e-copy for review.

Other Covid-themed nonfiction I have read:

Medical accounts

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

- Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

- Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel (reviewed for Shelf Awareness)

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

- Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

+ I have a proof copy of Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki, coming out in January.

Nature writing

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

- The Heeding by Rob Cowen (in poetry form)

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

- Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss

General responses

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

- The Rome Plague Diaries by Matthew Kneale

- Quarantine Comix by Rachael Smith (in graphic novel form; reviewed for Foreword Reviews)

- UnPresidented by Jon Sopel

+ on my Kindle: Alone Together, an anthology of personal essays

+ on my TBR: What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch

If you read just one… Make it Intensive Care by Gavin Francis. (And, if you love nature books, follow that up with The Consolation of Nature.)

Can you see yourself reading any of these?

The Fell by Sarah Moss for #NovNov

Sarah Moss’s latest three releases have all been of novella length. I reviewed Ghost Wall for Novellas in November in 2018, and Summerwater in August 2020. In this trio, she’s demonstrated a fascination with what happens when people of diverging backgrounds and opinions are thrown together in extreme circumstances. Moss almost stops time as her effortless third-person omniscient narration moves from one character’s head to another. We feel that we know each one’s experiences and motivations from the inside. Whereas Ghost Wall was set in two weeks of a late-1980s summer, Summerwater and now the taut The Fell have pushed that time compression even further, spanning a day and about half a day, respectively.

A circadian narrative holds a lot of appeal – we’re all tantalized, I think, by the potential difference that one day can make. The particular day chosen as the backdrop for The Fell offers an ideal combination of the mundane and the climactic because it was during the UK’s November 2020 lockdown. On top of that blanket restriction, single mum Kate has been exposed to Covid-19 via a café colleague, so she and her teenage son Matt are meant to be in strict two-week quarantine. Except Kate can’t bear to be cooped up one minute longer and, as dusk falls, she sneaks out of their home in the Peak District National Park to climb a nearby hill. She knows this fell like the back of her hand, so doesn’t bother taking her phone.

Over the next 12 hours or so, we dart between four stream-of-consciousness internal monologues: besides Kate and Matt, the two main characters are their neighbour, Alice, an older widow who has undergone cancer treatment; and Rob, part of the volunteer hill rescue crew sent out to find Kate when she fails to return quickly. For the most part – as befits the lockdown – each is stuck in their solitary musings (Kate regrets her marriage, Alice reflects on a bristly relationship with her daughter, Rob remembers a friend who died up a mountain), but there are also a few brief interactions between them. I particularly enjoyed time spent with Kate as she sings religious songs and imagines a raven conducting her inquisition.

What Moss wants to do here, is done well. My misgiving is to do with the recycling of an identical approach from Summerwater – not just the circadian limit, present tense, no speech marks and POV-hopping, but also naming each short chapter after a random phrase from it. Another problem is one of timing. Had this come out last November, or even this January, it might have been close enough to events to be essential. Instead, it seems stuck in a time warp. Early on in the first lockdown, when our local arts venue’s open mic nights had gone online, one participant made a semi-professional music video for a song with the refrain “everyone’s got the same jokes.”

That’s how I reacted to The Fell: baking bread and biscuits, a family catch-up on Zoom, repainting and clearouts, even obsessive hand-washing … the references were worn out well before a draft was finished. Ironic though it may seem, I feel like I’ve found more cogent commentary about our present moment from Moss’s historical work. Yet I’ve read all of her fiction and would still list her among my favourite contemporary writers. Aspiring creative writers could approach the Summerwater/The Fell duology as a masterclass in perspective, voice and concise plotting. But I hope for something new from her next book.

[180 pages]

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Other reviews:

Short Nature Books for #NovNov by John Burnside, Jim Crumley and Aimee Nezhukumatathil

#NovNov meets #NonfictionNovember as nonfiction week of Novellas in November continues!

Tomorrow I’ll post my review of our buddy read for the week, The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free from Project Gutenberg, here).

Today I review four nature books that celebrate marvelous but threatened creatures and ponder our place in relation to them.

Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction by John Burnside (2021)

[127 pages]

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

“Auks” tells the story of how we drove the Great Auk to extinction and likens it to whaling, two tragic cases of exploiting species for our own ends. The second and fourth essays stood out most to me. “The hint half guessed, the gift half understood” links literal species extinction with the loss of a sense of place. The notion of ‘property’ means that land becomes a space to be filled. Contrast this with places devoid of time and ownership, like Chernobyl. Although I appreciated the discussion of solastalgia and ecological grief, much of the material here felt a rehashing of my other reading, such as Footprints, Islands of Abandonment, Irreplaceable, Losing Eden and Notes from an Apocalypse. Some Covid references date this one in an unfortunate way, while the final essay, “Blossom Ruins,” has a good reason for mentioning Covid-19: Burnside was hospitalized for it in April 2020, his near-death experience a further spur to contemplate extinction and false hope.

The academic register and frequent long quotations from other thinkers may give other readers pause. Those less familiar with current environmental nonfiction will probably get more out of these essays than I did, though overall I found them worth engaging with.

With thanks to Little Toller Books for the proof copy for review.

Kingfisher and Otter by Jim Crumley (2018)

[59 pages each]

Part of Crumley’s “Encounters in the Wild” series for the publisher Saraband, these are attractive wee hardbacks with covers by Carry Akroyd. (I’ve previously reviewed his The Company of Swans.) Each is based on the Scottish nature writer’s observations and serendipitous meetings, while an afterword gives additional information on the animal and its appearances in legend and literature.

An unexpected link between these two volumes was beavers, now thriving in Scotland after a recent reintroduction. Crumley marvels that, 400 years after their kind could last have interacted with beavers, otters have quickly gotten used to sharing rivers – to him this “suggests that race memory is indestructible.” Likewise, kingfishers gravitate to where beaver dams have created fish-filled ponds.

Kingfisher was, marginally, my preferred title from the pair. It sticks close to one spot, a particular “bend in the river” where the author watches faithfully and is occasionally rewarded by the sight of one or two kingfishers. As the book opens, he sees what at first looks like a small brown bird flying straight at him, until the head-on view becomes a profile that reveals a flash of electric blue. As the Gerard Manley Hopkins line has it (borrowed for the title of Alex Preston’s book on birdwatching), kingfishers “catch fire.” Lyrical writing and self-deprecating honesty about the necessity of waiting (perhaps in the soaking rain) for moments of magic made this a lovely read. “Colour is to kingfishers what slipperiness is to eels. … Vanishing and theory-shattering are what kingfishers do best.”

In Otter, Crumley ranges a bit more widely, prioritizing outlying Scottish islands from Shetland to Skye. It’s on Mull that he has the best views, seeing four otters in one day, though “no encounter is less than unforgettable.” He watches them playing with objects and tries to talk back to them by repeating their “Haah?” sound. “Everything I gather from familiar landscapes is more precious as a beholder, as a nature writer, because my own constant presence in that landscape is also a part of the pattern, and I reclaim the ancient right of my own species to be part of nature myself.”

From time to time we see a kingfisher flying down the canal. Some of our neighbors have also seen an otter swimming across from the end of the gardens, but despite our dusk vigils we haven’t been so lucky as to see one yet. I’ve only seen a wild otter once, at Ham Wall Nature Reserve in Somerset. One day, maybe there will be one right here in my backyard. (Public library)

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (2020)

[160 pages]

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

The author’s Indian/Filipina family moved frequently for her mother’s medical jobs, and sometimes they were the only brown people around. Loneliness, the search for belonging and a compulsion to blend in are thus recurrent themes. As an adult, traveling for poetry residencies and sabbaticals exposes her to new species like whale sharks. Childhood trips back to India allowed her to spend time among peacocks, her favorite animal. In the American melting pot, her elementary school drawing of a peacock was considered unacceptable, but when she featured a bald eagle and flag instead she won a prize.

These pinpricks of the BIPOC experience struck me more powerfully than the actual nature writing, which can be shallow and twee. Talking to birds, praising the axolotl’s “smile,” directly addressing the reader – it’s all very nice, but somewhat uninformed; while she does admit to sadness and worry about what we are losing, her sunny outlook seemed out of touch at times. On the one hand, it’s great that she wanted to structure her fragments of memoir around amazing animals; on the other, I suspect that it cheapens a species to only consider it as a metaphor for the self (a vampire squid or potoo = her desire to camouflage herself in high school; flamingos = herself and other fragile long-legged college students; a bird of paradise = the guests dancing the Macarena at her wedding reception).

My favorite pieces were one on the corpse flower and the bookend duo on fireflies – she hits just the right note of nostalgia and warning: “I know I will search for fireflies all the rest of my days, even though they dwindle a little bit more each year. I can’t help it. They blink on and off, a lime glow to the summer night air, as if to say, I am still here, you are still here.”

With thanks to Souvenir Press for the free copy for review.

Any nature books on your reading pile?

Book Serendipity, September to October 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20–30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck. This used to be a quarterly feature, but to keep the lists from getting too unwieldy I’ve shifted to bimonthly.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Young people studying An Inspector Calls in Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi and Heartstoppers, Volume 4 by Alice Oseman.

- China Room (Sunjeev Sahota) was immediately followed by The China Factory (Mary Costello).

- A mention of acorn production being connected to the weather earlier in the year in Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian and Noah’s Compass by Anne Tyler.

- The experience of being lost and disoriented in Amsterdam features in Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss and Yearbook by Seth Rogen.

- Reading a book about ravens (A Shadow Above by Joe Shute) and one by a Raven (Fox & I by Catherine Raven) at the same time.

- Speaking of ravens, they’re also mentioned in The Elements by Kat Lister, and the Edgar Allan Poe poem “The Raven” was referred to and/or quoted in both of those books plus 100 Poets by John Carey.

- A trip to Mexico as a way to come to terms with the death of a loved one in This Party’s Dead by Erica Buist (read back in February–March) and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading from two Carcanet Press releases that are Covid-19 diaries and have plague masks on the cover at the same time: Year of Plagues by Fred D’Aguiar and 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici. (Reviews of both coming up soon.)

- Descriptions of whaling and whale processing and a summary of the Jonah and the Whale story in Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs and The Woodcock by Richard Smyth.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

- After having read two whole nature memoirs set in England’s New Forest (Goshawk Summer by James Aldred and The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell), I encountered it again in one chapter of A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Cranford is mentioned in Corduroy by Adrian Bell and Cut Out by Michèle Roberts.

- Kenneth Grahame’s life story and The Wind in the Willows are discussed in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading two books by a Jenn at the same time: Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Other Mothers by Jenn Berney.

- A metaphor of nature giving a V sign (that’s equivalent to the middle finger for you American readers) in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- Quince preserves are mentioned in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- There’s a gooseberry pie in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo.

- The ominous taste of herbicide in the throat post-spraying shows up in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

- People’s rude questioning about gay dads and surrogacy turns up in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and the DAD anthology from Music.Football.Fatherhood.

- A young woman dresses in unattractive secondhand clothes in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A mention of the bounty placed on crop-eating birds in medieval England in Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates and A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Hedgerows being decimated, and an account of how mistletoe is spread, in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- Listening to a dual-language presentation and observing that the people who know the original language laugh before the rest of the audience in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

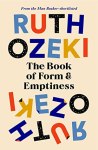

- A character imagines his heart being taken out of his chest in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- A younger sister named Nina in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and Sex Cult Nun by Faith Jones.

- Adulatory words about George H.W. Bush in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Thinking Again by Jan Morris.

- Reading three novels by Australian women at the same time (and it’s rare for me to read even one – availability in the UK can be an issue): Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, The Performance by Claire Thomas, and The Weekend by Charlotte Wood.

- There’s a couple who met as family friends as teenagers and are still (on again, off again) together in Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- The Performance by Claire Thomas is set during a performance of the Samuel Beckett play Happy Days, which is mentioned in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

- Nicholas Royle (whose White Spines I was also reading at the time) turns up on a Zoom session in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

- Richard Brautigan is mentioned in both The Mystery of Henri Pick by David Foenkinos and White Spines by Nicholas Royle.

- The Wizard of Oz and The Railway Children are part of the plot in The Book Smugglers (Pages & Co., #4) by Anna James and mentioned in Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with.

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with. Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

Katerina Canyon is from Los Angeles and now lives in Seattle. This is her second collection. As the poem “Involuntary Endurance” makes clear, you survive an upbringing like hers only because you have to. This autobiographical collection is designed to earn the epithet “unflinching,” with topics including domestic violence, parental drug abuse, and homelessness. When you hear that her father once handcuffed and whipped her autistic brother, you understand why “No More Poems about My Father” ends up breaking its title’s New Year’s resolution!

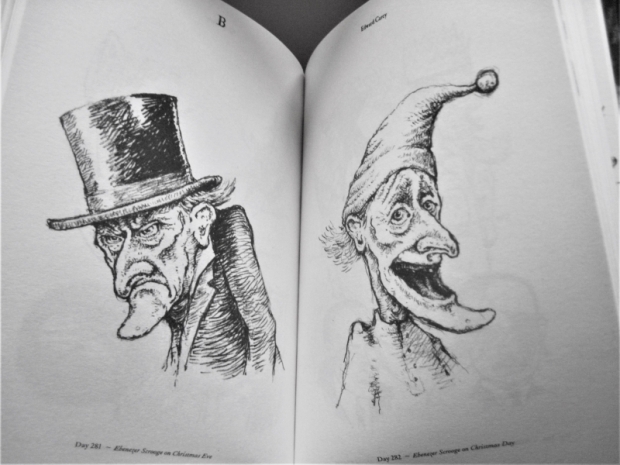

Katerina Canyon is from Los Angeles and now lives in Seattle. This is her second collection. As the poem “Involuntary Endurance” makes clear, you survive an upbringing like hers only because you have to. This autobiographical collection is designed to earn the epithet “unflinching,” with topics including domestic violence, parental drug abuse, and homelessness. When you hear that her father once handcuffed and whipped her autistic brother, you understand why “No More Poems about My Father” ends up breaking its title’s New Year’s resolution! I was a huge fan of Edward Carey’s

I was a huge fan of Edward Carey’s

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.  Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.

Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.  Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)  Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)

Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)  The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of  Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.

Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.  The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.

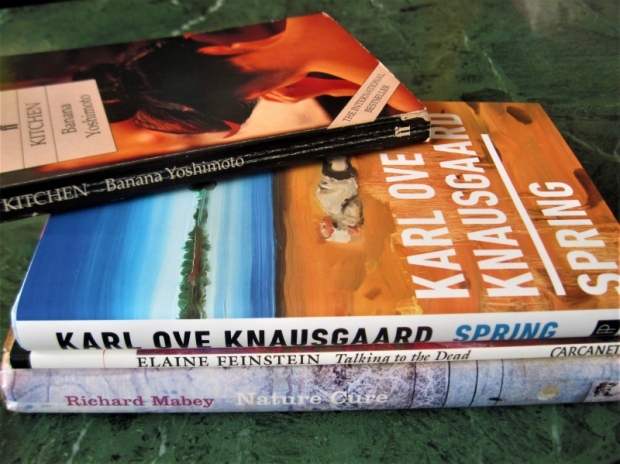

The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.  Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.

Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.  This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s

This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

Pilgrim Bell by Kaveh Akbar: An Iranian American poet imparts the experience of being torn between cultures and languages, as well as between religion and doubt, in this gorgeous collection of confessional verse. Food, plants, animals, and the body supply the book’s imagery. Wordplay and startling juxtapositions lend lightness to a wistful, intimate collection that seeks belonging and belief. (Coming out on August 3rd from Graywolf Press. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Pilgrim Bell by Kaveh Akbar: An Iranian American poet imparts the experience of being torn between cultures and languages, as well as between religion and doubt, in this gorgeous collection of confessional verse. Food, plants, animals, and the body supply the book’s imagery. Wordplay and startling juxtapositions lend lightness to a wistful, intimate collection that seeks belonging and belief. (Coming out on August 3rd from Graywolf Press. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)