#SciFiMonth: A Simple Intervention (#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth) & Station Eleven Reread

It’s rare for me to pick up a work of science fiction but occasionally I’ll find a book that hits the sweet spot between literary fiction and sci-fi. Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell are a few prime examples. It was the comparisons to Margaret Atwood and Kazuo Ishiguro, masters of the speculative, that drew me to my first selection, a Peirene Press novella. My second was a reread, 10 years on, for book club, whose postapocalyptic content felt strangely appropriate for a week that delivered cataclysmic election results.

A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai (2022; 2024)

[Translated from the German by Marielle Sutherland]

Meret is a nurse on a surgical ward, content in the knowledge that she’s making a difference. Her hospital offers a pioneering procedure that cures people of mental illnesses. It’s painless and takes just an hour.

The doctor had to find the affected area and put it to sleep, like a sick animal. That was his job. Mine was to keep the patients occupied. I was to distract them from what was happening and keep them interacting with me. As long as they stayed awake, we knew the doctor and his instruments had found the right place.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

The story revolves around Meret’s emotional involvement in the case of Marianne, a feisty young woman who has uneasy relationships with her father and brothers. The two play cards and share family anecdotes. Until the last few chapters, the slow-moving plot builds mostly through flashbacks, including to Meret’s affair with her fellow nurse, Sarah. This roommates-to-lovers thread reminded me of Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue. When Marianne’s intervention goes wrong, Meret and Sarah doubt their vocation and plan an act of heroism.

Inokai invites us to ponder whether what we perceive as defects are actually valuable personality traits. More examples of interventions and their aftermath would be a useful point of comparison, though, and the pace is uneven, with a lot of unnecessary-seeming backstory about Meret’s family life. In the letter that accompanied my review copy, Inokai explained her three aims: to portray a nurse (her mother’s career) because they’re underrepresented in fiction, “to explore our yearning to cut out our ‘demons’,” and to offer “a queer love story that was hopeful.” She certainly succeeds with those first and third goals, but with the central subject I felt she faltered through vagueness.

Born in Switzerland, Inokai now lives in Berlin. This also counts as my first contribution to German Literature Month; another is on the way!

[187 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

For synopsis and analysis I can’t do better than when I reviewed this for BookBrowse a few months after its release, so I’d direct you to the full text here. (It’s slightly depressing for me to go back to old reviews and see that I haven’t improved; if anything, I’ve gotten lazier.) A couple book club members weren’t as keen, I think because they’d read a lot of dystopian fiction or seen many postapocalyptic films and found this vision mild and with a somewhat implausible setup and tidy conclusion. But for me this and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road have persisted as THE literary depictions of post-apocalypse life because they perfectly blend the literary and the speculative in an accessible and believable way (this was a National Book Award finalist and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award), contrasting a harrowing future with nostalgia for an everyday life that we can already see retreating into the past.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

Station Eleven has become a real benchmark for me, against which I measure any other dystopian novel. On this reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and enjoyed rediscovering the links between characters and storylines. I remembered a few vivid scenes and settings. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work, particularly The Glass Hotel (island off Vancouver, international shipping and finance) but also Sea of Tranquility (music, an airport terminal). I haven’t read her first three novels, but wouldn’t be surprised if they have additional links.

The two themes that most struck me this time were the enduring power of art and how societal breakdown would instantly eliminate the international – but compensate for it with the return of the extremely local. At a time when it feels difficult to trust central governments to have people’s best interests at heart, this is a rather comforting prospect. Just in my neighbourhood, I see how we implement this care on a small scale. In settlements of up to a few hundred, the remnants of Station Eleven create something like normal life by Year 20.

Book club members sniped that the characters could have better pooled skills, but we agreed that Mandel was wise to limit what could have been tedious details about survival. “Survival is insufficient,” as the Traveling Symphony’s motto goes (borrowed from Star Trek). Instead, she focuses on love, memory, and hunger for the arts. In some ways, this feels prescient of Covid-19, but even more so of the climate-related collapse I expect in my lifetime. I’ve rated this a little bit higher the second time for its lasting relevance. (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

Some favourite passages:

the whole of Chapter 6, a bittersweet litany that opens “An incomplete list: No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below” and includes “No more pharmaceuticals,” “No more flight,” and “No more countries”

“what made it bearable were the friendships, of course, the camaraderie and the music and the Shakespeare, the moments of transcendent beauty and joy”

“The beauty of this world where almost everyone was gone. If hell is other people, what is a world with almost no people in it?”

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley (Blog Tour)

Silver Moon, one of the Charing Cross Road bookshops, was a London institution from 1984 until its closure in 2001. “Feminism and business are strange bedfellows,” Jane Cholmeley soon realised, and this book is her record of the challenges of combining the two. On the spectrum of personal to political, this is much more manifesto than memoir. She dispenses with her own story (vicar’s tomboy daughter, boarding school, observing racism on a year abroad in Virginia, secretarial and publishing jobs, meeting her partner) via a 10-page “Who Am I?” opening chapter. However, snippets of autobiography do enter into the book later on; in one of my favourite short chapters, “Coming Out,” Cholmeley recalls finally telling her mother that she was a lesbian after she and Sue had been together nearly a decade.

The mid-1980s context plays a major role: Thatcherite policies (Section 28 outlawing the “promotion of homosexuality”), negotiations with the Greater London Council, and trying to share the landscape with other feminist bookshops like Sisterwrite and Virago. Although there were some low-key rivalries and mean-spirited vandalism, a spirit of camaraderie generally prevailed. Cholmeley estimates that about 30% of the shop’s customers were men, but the focus here was always on women. The events programme featured talks by an amazing who’s-who of women authors, Cholmeley was part of the initial roundtable discussions in 1992 that launched the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize), and the café was designated a members’ club so that it could legally be a women-only space.

I’ve always loved reading about what goes on behind the scenes in bookshops (The Diary of a Bookseller, Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop, The Sentence, The Education of Harriet Hatfield, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, and so on), and Cholmeley ably conveys the buzzing girl-power atmosphere of hers. There is a fun sense of humour, too: “Dyke and Doughnut” was a potential shop name, and a letter to one potential business partner read, “you already eat lentils, and ride a bicycle, so your standard of living hasn’t got much further to fall, we happen to like you an awful lot, and think we could all work together in relative harmony”.

However, the book does not have a narrative per se; the “A Day in the Life of… (1996)” chapter comes closest to what those hoping for a bookseller memoir might be expecting, in that it actually recreates scenes and dialogue. The rest is a thematic chronicle, complete with lists, sales figures, profitability charts, and excerpted documents, and I often got lost in the detail. The fact that this gives the comprehensive history of one establishment makes it a nostalgic yearbook that will appeal most to readers who have a head for business, were dedicated Silver Moon customers, and/or hold a particular personal or academic interest in the politics of the time and the development of the feminist and LGBT movements.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Mudlark for the free copy for review.

Buy A Bookshop of One’s Own from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was happy to be part of the blog tour for the release of this book. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again. At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.

Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend.

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend. This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in

This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in  The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels  Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

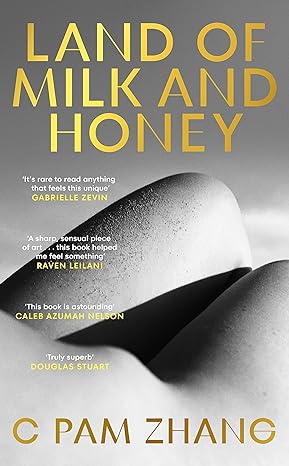

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot. A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.” Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood. I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through. Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!