Tag Archives: metafiction

#NovNov25 and #GermanLitMonth: Kästner, Kehlmann & Kracht

Our trip to Germany in September whetted my appetite to read more German-language fiction, and November also being German Literature Month (hosted this year by Caroline of Beauty Is a Sleeping Cat and Tony of Tony’s Reading List) was a perfect excuse. K names only this year, please. (Perhaps next year I’ll make it S and finally get to those Sebald and Seethaler novels I have on the shelf.) These three works – a children’s classic, a set of linked short stories about the writer’s craft, and a mother–son spending spree – have coy metafictional touches, plus there’s a connection I wasn’t expecting between the Kehlmann and Kracht. All: ![]()

Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner (1929; 1931)

[Translated by Eileen Hall]

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]

Fame by Daniel Kehlmann (2009; 2010)

[Translated by Carol Brown Janeway]

I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction (Measuring the World) and contemporary metafiction (F is one of my all-time favourites) in the past. These nine linked stories feature writers and their characters, actors and their look-alikes, and are about how life translates into – or is sometimes transformed by – art. Ralf Tanner starts to feel like he doesn’t exist when his calls gets diverted to someone else’s phone and an impersonator is more convincing at playing him than he is himself. Leo Richter’s new girlfriend is curiously similar to his most famous character, Lara Gaspard, a doctor working for a medical charity. Crime writer Maria Rubinstein takes Leo’s place on a cultural exchange to Central Asia and gets stuck in a Kafka-esque situation without a visa. Leo’s fan and Ralf’s call recipient are subjects of their own stories. References to Miguel Auristos Blanco’s spiritual self-help books recur and he, too, eventually becomes a character. I liked the pointed little jokes about what writers have to put up with (“Do you know how often I’ve been asked today where I get my ideas from? Fourteen. And nine times whether I work in the morning or the afternoon,” Leo complains). Mostly, these stories struck me as clever yet had me wondering what the point was. My favourite was “Rosalie Goes Off to Die,” in which Leo’s character travels to Zurich for an assisted death but he the writer decides to interfere before she can get her last wish. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [206 pages – but fairly large print]

I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction (Measuring the World) and contemporary metafiction (F is one of my all-time favourites) in the past. These nine linked stories feature writers and their characters, actors and their look-alikes, and are about how life translates into – or is sometimes transformed by – art. Ralf Tanner starts to feel like he doesn’t exist when his calls gets diverted to someone else’s phone and an impersonator is more convincing at playing him than he is himself. Leo Richter’s new girlfriend is curiously similar to his most famous character, Lara Gaspard, a doctor working for a medical charity. Crime writer Maria Rubinstein takes Leo’s place on a cultural exchange to Central Asia and gets stuck in a Kafka-esque situation without a visa. Leo’s fan and Ralf’s call recipient are subjects of their own stories. References to Miguel Auristos Blanco’s spiritual self-help books recur and he, too, eventually becomes a character. I liked the pointed little jokes about what writers have to put up with (“Do you know how often I’ve been asked today where I get my ideas from? Fourteen. And nine times whether I work in the morning or the afternoon,” Leo complains). Mostly, these stories struck me as clever yet had me wondering what the point was. My favourite was “Rosalie Goes Off to Die,” in which Leo’s character travels to Zurich for an assisted death but he the writer decides to interfere before she can get her last wish. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [206 pages – but fairly large print]

Eurotrash by Christian Kracht (2021; 2024)

[Translated by Daniel Bowles]

This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

Spotted in my local Waterstones…

The 2025 McKitterick Prize Winner & SoA Awards Ceremony

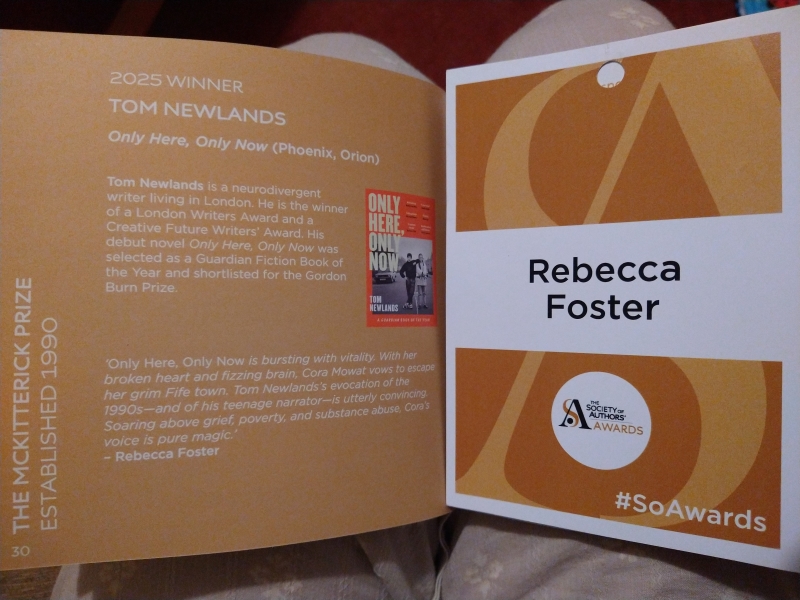

Yesterday the Society of Authors’ awards were announced and the prizes handed out at a ceremony in London. As a McKitterick Prize judge, I was asked last month to give a 50-word blurb on the shortlist as a whole—

Each of these six novels has a fully realized style. So confident and inviting are they that it’s hard to believe they are debuts. With nuanced characters and authentic settings and dilemmas, they engage the mind and delight the emotions. I will be following these authors’ careers with keen interest.

—and on each individual shortlisted title:

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

In Monumenta, Lara Haworth braids satire, magic realism, and metafiction into a compact and surprising meditation on how we seek to memorialise the tragedies of history.

Set in small-town Ireland, The Coast Road is a subtle, compassionate novel in which the characters learn to write their own stories rather than bow to convention and fate. Alan Murrin is a must-read author for fans of Claire Keegan, Louise Kennedy, and Colm Tóibín.

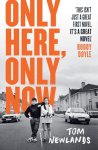

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Our winner was Tom Newlands for Only Here, Only Now and our runner-up was Lauren Elkin for Scaffolding. (What an honour to have my blurb for the former used in the winners press release, the ceremony programme, and social media publicity.)

Newlands was also a runner-up for the ADCI Literary Prize “for a disabled or chronically ill writer, for an outstanding novel containing a disabled or chronically ill character or characters.” Here’s an excerpt from his statement for the press release:

To have my debut novel recognised in these two categories is particularly meaningful for me because they are linked by my experience. I didn’t start writing until the age of 40, in large part because growing up neurodivergent I didn’t feel my thought processes or methods of working were compatible with the production of a novel. There were no role models out there publishing stories like mine, and in the end, I wrote Only Here, Only Now because I couldn’t find the novel I wanted to read – a warm, vivid and funny story that examined poverty, disability and belonging, and that featured characters rarely found in British fiction.

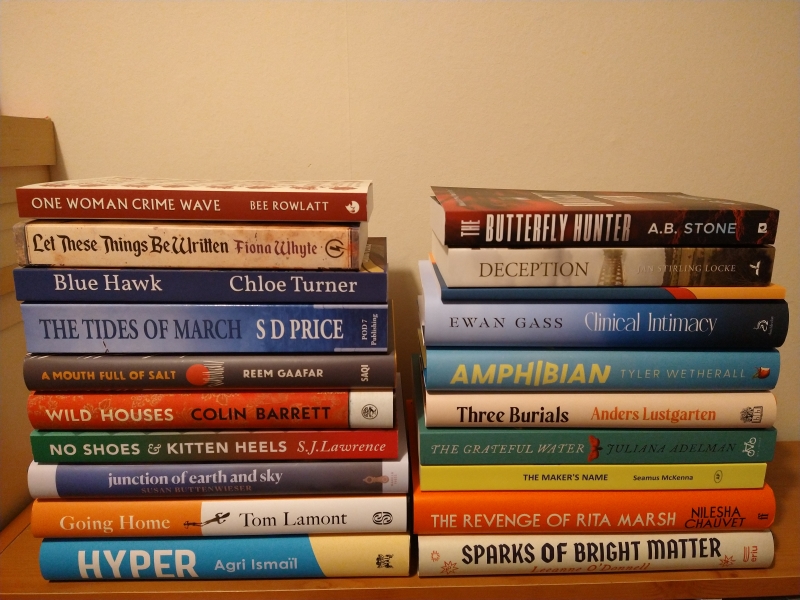

Looking back to early on in this prize journey (which started back in November) … here was some of my early reading:

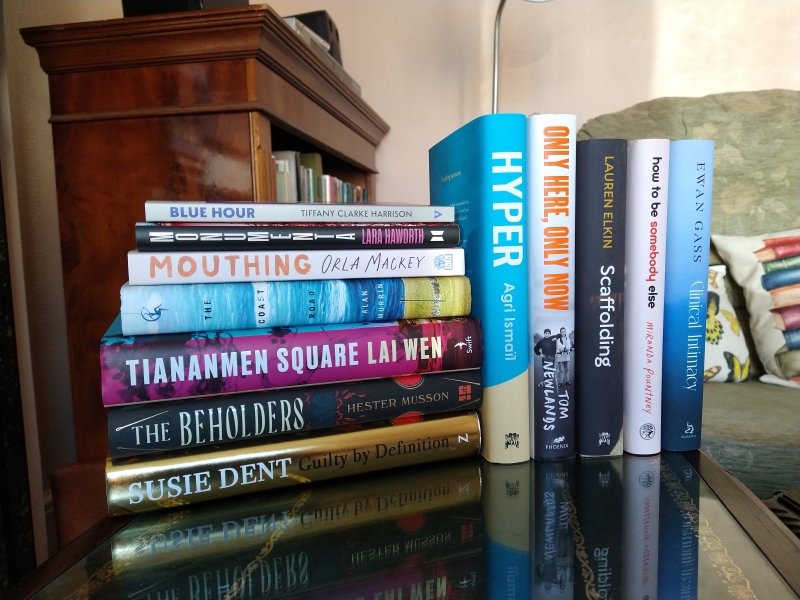

And our longlist:

A couple of my favourite books from my reading that didn’t make the shortlist were:

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Following a Kurdish family across several decades, this is a zeitgeist-y story that examines questions of national and personal autonomy. With its Dubai, Baghdad, London, and New York settings, it sets the second generation’s luxury, high finance, and fully online worlds against their parents’ bitter experience of exile after a failed independence movement. With its themes of dysfunction and failures and the long view of how we got here from there, it reminded me of Jonathan Franzen’s body of work.

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

This is the addictively readable story of Dylan, a late-thirties English woman who gives up her New York City advertising job and ponders authorship and motherhood while house-sitting an acquaintance’s apartment—and carrying on an affair with the married downstairs neighbour. As we see her interact with family and friends, we come to appreciate her not as some stereotypical ‘sad girl’ or ‘disaster woman’, but as an Everywoman seeking the time and space to become herself. It’s a sharp and witty novel for fans of Sally Rooney.

For the first time, I got to attend the SoA Awards ceremony in person yesterday. It was a hot day to be travelling in London, and after the oven of the Bakerloo line I was grateful to escape into the cool of Southwark Cathedral and its grounds. It was such a juxtaposition between the sleek City architecture and the ancient refuge of a church.

I worried that on such a warm and then busy day Hodge the cathedral cat wouldn’t show himself, but as I picked up my name badge he was asking to be let inside from the courtyard. He didn’t seem interested in strokes so I followed him at a respectful distance and let him settle in for a watchful rest.

Nominated authors and judges were treated to an exceptional afternoon tea, followed by the ceremony and drinks reception. It was lovely to meet my fellow judges Anietie Isong and Kathy O’Shaughnessy (author of the fantastic In Love with George Eliot, which won the SoA’s Paul Torday Memorial Prize) in the flesh as I’d only met them on Zoom before. We chatted a good bit with Lara Haworth, one of our shortlistees, and with Anne Booth, one of the Queen’s Knickers Award (children’s books) nominees, and also got to briefly meet Tom Newlands when he arrived for the ceremony. I always look out for literary ‘celebrities’ at such events and yesterday spotted Naomi Alderman, Caroline Bird, Joanne Harris and Alice Jolly.

Dean Rev. Mark Oakley gave a welcome address via video, praising authors for bringing “resonance” rather than just “relevance.” He exhorted us, in the words of David Copperfield, to “read as if for life.” Joseph Coelho then gave a terrific keynote speech celebrating words written by humans (as opposed to an inaccurate AI-written bio of himself that he once encountered) and encouraging shortlistees, especially, to take time to bask in their achievement. Rejection is an ongoing, annual thing for him even at this stage of his career – he still remembers the £50 poetry gigs, changing in library toilets and school staff rooms; and the 12 years he spent trying to get published – even after he became the youngest-ever children’s laureate in 2022. “Wait for no one,” he challenged us: no one is going to give you permission or come save you, so go out there and do what you’re meant to do.

What an all-round fantastic experience this was! I’m so grateful to the Society of Authors for the opportunity.

Other notable winners announced yesterday included:

- Ashani Lewis (the only double winner): the Betty Trask Prize and Somerset Maugham award for Winter Animals

- Hisham Matar & Elif Shafak: the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize (for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home), joint winners for My Friends and There Are Rivers in the Sky

May Graphic Novels by Alison Bechdel, Peter Kuper & Craig Thompson

May has been chock-full of new releases for me! For this first batch of reviews, I’m featuring three fantastic graphic novels that have made it onto my Best of 2025 (so far) list. I don’t read graphic books as often as I’d like to – my library tends to major on superhero comics and manga, which aren’t my cup of tea – but I sometimes get a chance to access them for paid review purposes. (The first two below are ones I was sent for potential Shelf Awareness reviews, but I missed the deadlines.) Reading these took me back to the early 2010s when I worked for a university library in South London and would walk to Lambeth Library on my lunch breaks to borrow huge piles of books, mostly taking advantage of their excellent graphic novel selection. That was where my education and fascination began.

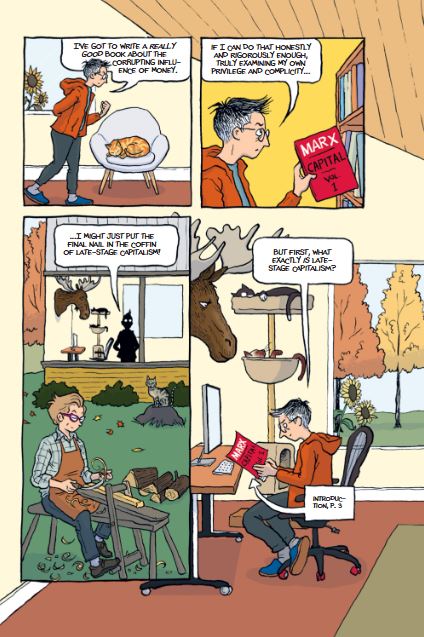

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now. Fun Home was among the first graphic books I read and is a great choice if you’re new to this form of storytelling. It’s a family memoir about her father’s funeral home business and closeted lifestyle, which emerged shortly after her own coming-out – and shortly before his accidental death. In Spent, Alison and her handy wife Holly live on a Vermont pygmy goat farm. Alison has writer’s block and is struggling financially despite her famous memoir about her taxidermist father having been made into a successful TV series, Death & Taxidermy. Mostly, she’s consumed with anxiety about the state of the world, what with the ongoing pandemic, her sister’s right-wing opinions, and the litany of awful headlines. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” she exclaims.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now. Fun Home was among the first graphic books I read and is a great choice if you’re new to this form of storytelling. It’s a family memoir about her father’s funeral home business and closeted lifestyle, which emerged shortly after her own coming-out – and shortly before his accidental death. In Spent, Alison and her handy wife Holly live on a Vermont pygmy goat farm. Alison has writer’s block and is struggling financially despite her famous memoir about her taxidermist father having been made into a successful TV series, Death & Taxidermy. Mostly, she’s consumed with anxiety about the state of the world, what with the ongoing pandemic, her sister’s right-wing opinions, and the litany of awful headlines. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” she exclaims.

Then Alison has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored in Spent, which is composed of 12 “episodes” titled after Marxist terminology. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living: a commune, a throuple, nonbinary identity, unpaid internships, Just Stop Oil demos, and the influencer lifestyle versus rejection of technology. It’s (auto)fiction exaggerated to the brink of absurdity, with details changed enough to mock but not enough to hide (e.g., she’s published by “Megalopub,” the hardware store is “Home Despot,” her show airs on “Schmamazon”).

Tiny details in the drawings reward close attention, such as Alison and Holly’s five cats’ antics during their morning routine, and a stuffed moose head rolling its eyes. It’s the funniest I can remember Bechdel being, with much broad humour derived from the outrageous screen mangling of her book – cannibalism, volcanoes and dragons come out of nowhere – and her middle-class friends’ hand-wringing over their liberal credentials. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close as Alison has the epiphany that she can’t fix everything herself so must simply do what she can, “with a little help from her annoying, tender-hearted, and utterly luminous friends.”

Accessed as an e-book from Mariner Books. Published in the UK by Jonathan Cape (Penguin).

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s Ruins, which features monarch migration and has as protagonist a laid-off Natural History Museum entomologist. Here insects have even more of a starring role. The E. O. Wilson epigraph sets the stage: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” We follow an African American brother-and-sister pair, the one dubious and the other eager, as they walk downtown to the New York Public Library. The sister, who holds a PhD in entomology, promises that its exhibition on insects is going to be amazing. But just before they reach the building, a red alert flashes up on every smartphone and sirens start blaring. A week later, the city is a ruin of overturned cabs and debris. Only insects remain and, group by group, they guide readers through the empty exhibit, interacting within and across species.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s Ruins, which features monarch migration and has as protagonist a laid-off Natural History Museum entomologist. Here insects have even more of a starring role. The E. O. Wilson epigraph sets the stage: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” We follow an African American brother-and-sister pair, the one dubious and the other eager, as they walk downtown to the New York Public Library. The sister, who holds a PhD in entomology, promises that its exhibition on insects is going to be amazing. But just before they reach the building, a red alert flashes up on every smartphone and sirens start blaring. A week later, the city is a ruin of overturned cabs and debris. Only insects remain and, group by group, they guide readers through the empty exhibit, interacting within and across species.

It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. I loved the scenes of mosquitoes and ants railing against how they’ve been depicted as villainous, and dignified dung beetles resisting scatological jokes and standing up for their importance in ecosystems. There are interesting interludes about insects in literature (not just Kafka and Nabokov, but the Japanese graphic novel The Book of Human Insects by Osamu Tezuka), and unsung heroines of entomology get their moment in the sun. The pages in which Margaret Collins, an African American termite researcher in the 1950s, and Rachel Carson appear to a dragonfly as ghosts and tell their stories of being dismissed by male researchers were among my favourites. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

Accessed as an e-book from W. W. Norton & Company.

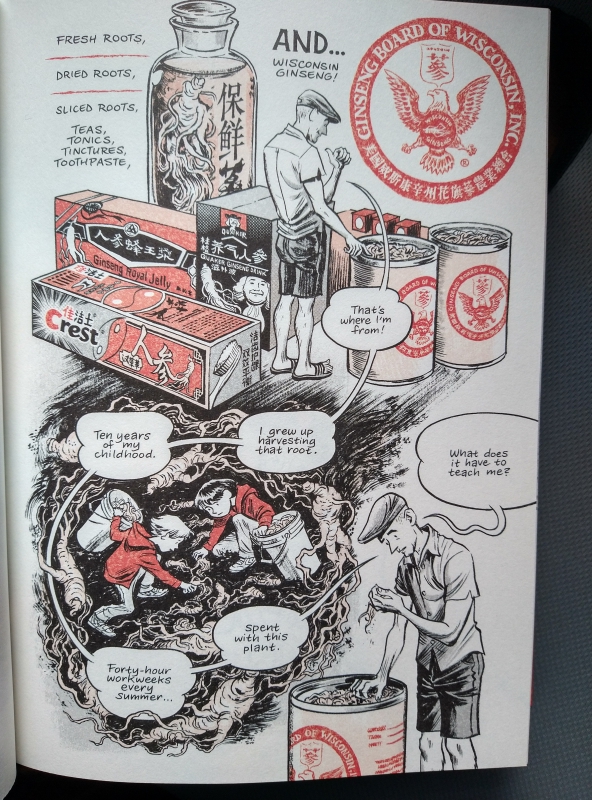

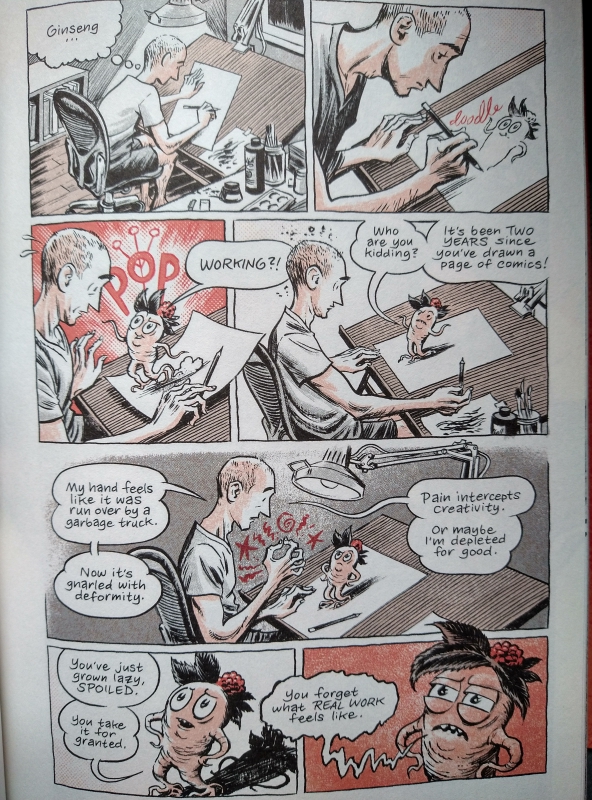

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir, Blankets, about his first love and loss of faith. When I read this blurb, I worried the niche subject couldn’t possibly sustain my attention for nearly 450 pages. But I was wrong; this is a vital book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. Theirs was a blue collar and highly religious family, but Thompson and his little brother Phil were allowed to spend their earnings from the back-breaking labour of weeding and picking rocks as they pleased. Each hour, each dollar, meant a new comic from the pharmacy. “Comics helped me survive my childhood. But what will help me survive my adulthood?” Thompson asks.

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir, Blankets, about his first love and loss of faith. When I read this blurb, I worried the niche subject couldn’t possibly sustain my attention for nearly 450 pages. But I was wrong; this is a vital book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. Theirs was a blue collar and highly religious family, but Thompson and his little brother Phil were allowed to spend their earnings from the back-breaking labour of weeding and picking rocks as they pleased. Each hour, each dollar, meant a new comic from the pharmacy. “Comics helped me survive my childhood. But what will help me survive my adulthood?” Thompson asks.

Together with Phil, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation practices, lore, and medicinal uses. As he meets producers – including a Hmong man whose early life mirrors his own – he feels sheepish about how he makes a living: “I carry this working-class guilt – what I do isn’t real work.” When his livelihood is threatened by worsening autoimmune conditions, he tries everything from acupuncture to psychotherapy to save his hands and his creativity.

This chunky book has an appealing earth-tones palette and shifts smoothly between locations and styles, memories and research. When interviewing growers and Chinese medicine practitioners, the depictions are almost photorealistic, but there are also superhero pastiche panels and a cute ginseng mascot who pops up throughout the book. Like Spent, this pulls in class and economic issues in a lighthearted way and also explores its own composition process.

The story of ginseng is often sobering, involving the exploitation of immigrants (in the Notes, Thompson regrets that he was unable to speak with any of the Mexican migrant workers on whom the American ginseng harvest now depends), soil degradation, and pesticide pollution. The roots of the title are both literal and symbolic of the family story that unfolds in parallel. Both strands are captivating, but especially the autobiographical material: Thompson’s relationship with Phil, his new understanding but ongoing frustration with his parents, and the way all three siblings exhibit the damage of their upbringing – Phil’s marriage is crumbling; their sister Sarah, who has moved 26 times as an adult, wonders what she’s running from. A conversation with a Chinese herbal pharmacist gets to the heart of the matter: “I learned home is not WHERE I am. Home is HOW I am.”

Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers out there.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. Published in the USA by Pantheon (Penguin).

Book Serendipity, Mid-February to Mid-April

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- The protagonist isn’t aware that they’re crying until someone tells them / they look in a mirror in The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler.

- A residential complex with primal scream therapy in Confessions by Catherine Airey and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

- Memories of wiping down groceries during the early days of the pandemic in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- A few weeks before I read Maurice and Maralyn by Sophie Elmhirst, I’d finished reading the author’s husband’s debut novel (Going Home by Tom Lamont); I had no idea of the connection between them until I got to her Acknowledgements.

- A mention of the same emergency money passing between friends in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez ($20) and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey ($100).

- Autobiographical discussions of religiosity and anorexia in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey and Godstruck by Kelsey Osgood.

- The theme of the dark night sky in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, followed almost immediately by Night Magic by Leigh Ann Henion.

- Last year I learned about Marina Abramović’s performance art where she and her ex trekked to China’s Great Wall from different directions, met in the middle, and continued walking away to dramatize their breakup in The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton. Recently I saw it mentioned again in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey. Abramović’s work is also mentioned in Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly and is the basis for the opening track on Anne-Marie Sanderson’s album Old Light, “Amethyst Shoes.”

- The idea of running towards danger appears in Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s essay in Edge of the World, a queer travel anthology edited by Alden Jones; and the bibliography of The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

- I then read another Alex Marzano-Lesnevich essay in quick succession (both were excellent, by the way) in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate.

- A scene in which a woman goes to a police station and her concerns are dismissed because she has no evidence and the man/men’s behaviour isn’t ‘bad enough’ in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- Too many details as the sign of a lie in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler.

- Scenes of throwing all of a spouse’s belongings out on the yard/street in Old Soul by Susan Barker, How to Survive Your Mother by Jonathan Maitland, and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- Reading two lost American classics about motherhood and time spent in a mental institution at the same time: The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman and I Am Clarence by Elaine Kraf.

- Disorientation underwater: a literal experience in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, then used as a metaphor for what it was like to be stuck in a blizzard on Annapurna in 2014 in The Secret Life of Snow by Giles Whittell.

- A teenager who has a job cleaning hotels in Old Soul by Susan Barker and I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell. (In Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue, Maria is also a teenaged cleaner, but of office buildings.)

- A vacuum cleaner bag splits in Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund – in the latter it’s deliberate, searching for evidence of the character’s late son after cleaning his room.

- An ailing tree or trees that have to be cut down in one story of The Accidentals by Guadalupe Nettel and The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- Buchenwald was mentioned in one poem each in A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi and The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley.

- A reference to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass in To Have or to Hold by Sophie Pavelle and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- A mentally unwell woman deliberately burns her hands in I Am Clarence by Elaine Kraf and Every Day Is Mother’s Day by Hilary Mantel.

- A mention of the pollution caused by gas stoves in We Do Not Part by Han Kang and The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- An art installation involving part-buried trees was mentioned in Immemorial by Lauren Markham and then I encountered a similar project a few months later in We Do Not Part by Han Kang. Burying trees as a method of carbon storage is then discussed in The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- Imagining the lives of the people living in an apartment you didn’t end up renting in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and one story of The Accidentals by Guadalupe Nettel.

- The Anthropocene is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes.

- I was reading three debut novels from the McKitterick Prize longlist at the same time, all of them with very similar page counts of 383, 387, and 389 (i.e., too long!).

- Being appalled at an institutionalized mother’s appearance in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Every Day Is Mother’s Day by Hilary Mantel.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

- A lesbian couple in New Mexico, the experience of being watched through a window, and the mention of a caftan/kaftan, in Old Soul by Susan Barker and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Refusal to go to a hospital despite being in critical condition in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- It’s not a niche stylistic decision anymore; I was reading four novels with no speech marks at the same time: Old Soul by Susan Barker, Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin, The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes, and We Do Not Part by Han Kang. [And then, a bit later, three more: Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz, Mouthing by Orla Mackey, and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.]

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Responding to the 2021 murder of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in Foreign Fruit by Katie Goh and Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon.

- Disposing of a late father’s soiled mattress in Mouthing by Orla Mackey and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A Jewish care home for the elderly in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Joanna Rakoff’s essay in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About (ed. Michele Filgate).

- A woman has no memory between leaving a bar and first hooking up with the man she’s having an affair with in If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

- A pygmy goat as a pet (and a one-syllable, five-letter S title!) in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A Brooklyn setting and thirtysomething female protagonist in Sleep by Honor Jones, So Happy for You by Celia Laskey, and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A mention of the American Girl historical dolls franchise in Sleep by Honor Jones and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard, both of which I’m reviewing early for Shelf Awareness.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

- The protagonist’s therapist asks her to find more precise words for her feelings in Blue Hour by Tiffany Clarke Harrison and So Happy for You by Celia Laskey.

- The protagonist “talks” with a dying dog or cat in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

- The Rapunzel fairytale is a point of reference in In the Evening, We’ll Dance by Anne-Marie Erickson and Secret Agent Man by Margot Singer, both of which I was reading early for Foreword Reviews.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Paul Auster Reading Week, II: Baumgartner & Travels in the Scriptorium (#AusterRW25 #ReadIndies)

It’s the final day of Annabel’s Paul Auster Reading Week and, after last week’s reviews of Invisible and Siri Hustvedt’s The Blindfold, I’m squeaking in with a short review of his final novel, Baumgartner, which Annabel chose as the buddy read and Cathy also wrote about. I paired it at random with another of his novellas and found that the two have a similar basic setup: an elderly man being let down by his body and struggling to memorialize what is important from his earlier life. They also happen to feature a character named Anna Blume, and other character names recur from his previous work. I wonder how fair it would be to say that most of Auster’s novels have the same autofiction-inspired protagonist, and are part of the same interlocking universe (à la David Mitchell and Elizabeth Strout)?

Baumgartner (2023)

Sy Baumgartner is a Princeton philosophy professor nearing retirement. The accidental death of his wife, Anna Blume, a decade ago, is still a raw loss he compares to a phantom limb. Only now can he bring himself to consider 1) proposing marriage to his younger colleague and longtime casual girlfriend, Judith Feuer, and 2) allowing a PhD student to sort through reams of Anna’s unpublished work, including poetry, translations and unfinished novels. The book includes a few of her autobiographical fragments, as well as excerpts from his writings, such as an account of a trip to Ukraine to explore his heritage (elsewhere we learn his mother’s name was Ruth Auster) and a précis of his book about car culture.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

It’s not this that makes Baumgartner feel incomplete so much as the fact that any of its threads might have been expanded into a full-length novel. Maybe Auster had various projects on the go at the time of his final illness and combined them. That could explain the mishmash. I also had the odd sense that there were unconscious pastiches of other authors. Baumgartner reminds me a lot of James Darke, the curmudgeonly widower in Rick Gekoski’s pair of novels. When Baumgartner speaks to his dead wife on the telephone, I went hunting through my notes because I knew I’d encountered that specific plot before (the short story “The Telephone” by Mary Treadgold, collected in Fear, edited by Roald Dahl). The Ukraine passage might have come from Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer. So, for me, this was less distinctive as Auster works go. However, it’s gently readable and not formally challenging so it’s a pleasant valedictory volume if not the best representative of his oeuvre. (Public library) ![]()

Travels in the Scriptorium (2006)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)![]()

Faber, Auster’s longtime publisher, counts towards Reading Independent Publishers Month.

Paul Auster Reading Week: Invisible (#ReadIndies) & Siri Hustvedt’s The Blindfold (#AusterRW25)

The first time Annabel ran a Paul Auster Reading Week, in 2020, it was a great excuse for me to read six of his books (Winter Journal and The New York Trilogy were amazing; I also really enjoyed Oracle Night). I won’t manage so many this time, but maybe three, as well as one by his widow, Siri Hustvedt. Auster would have been 78 today but died of lung cancer in 2024. As a buddy read, Annabel is inviting people to read his final novel, Baumgartner. I’m partway through that and have another of his novellas waiting in the wings in case I find time.

For now, I’m focusing on a novel that exemplifies some recurring elements of his fiction: a book within a book, fragmented narratives, differing perspectives, cryptic events and the inscrutability of memory and language. I’m pairing it with Hustvedt’s debut novel, which is – not coincidentally, I should think – similarly intricate, weird and unsettling.

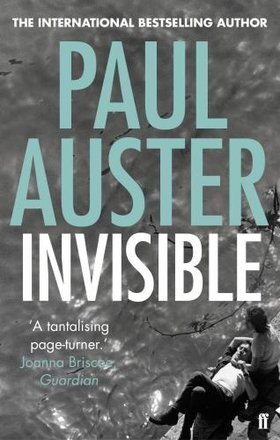

Invisible (2009)

To start with, I thought we were in autofiction territory, but Auster swiftly adopts a more typical metafictional approach. Adam Walker is a 20-year-old would-be poet studying at Columbia University in 1967. At a party he meets Rudolf Born, a visiting international affairs professor from Paris, and it seems a good omen: Born invests generously in Adam’s literary magazine and also seems open to sharing his beautiful girlfriend, Margot. But when the men are caught up in an attempted mugging, Adam turns against his idol.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

I can’t say more about the themes without giving too much away, but this is a provocative novel that makes you question how truth is created or preserved. Who has the right to tell the story, and will justice be done? I wouldn’t say I enjoyed it, but I certainly admired how it was constructed. Auster conjures such a sense of unease, and I always felt like I had no idea what might happen next. With no speech marks, it all flows together in a compulsively readable way. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Faber, Auster’s longtime publisher, counts towards Reading Independent Publishers Month.

The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt (1992)

“Strange, I thought. Everything is strange.”

I read Hustvedt (The Blazing World) well before I ever tried Auster, and wouldn’t have realized then how similar their books are; they almost seem part of the same body of work. Was Hustvedt a fan or a student of his before they married? I don’t actually know and am loath to dispel the mystery for myself by looking into it. Anyway, there are striking connections between this and Invisible: the narrator is fairly autobiographical and a Columbia University student, the novel is in four loosely connected parts, and the sordid content culminates in a sudden, odd ending. (There’s also the little Easter egg here of “I heard someone shout the name Paul.”) But overall, this is more reminiscent of The New York Trilogy in its surreal randomness and subtly symbolic naming (e.g., the landlord is Mr. Then).

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

I worked out that the chronological order of the parts is 2 – 4 – 3 – 1, with 1 including a recap of the others. The sections feel like separate vignettes, perhaps reflecting Hustvedt’s previous experience with the short story form, and make a less than satisfying whole. I was most engaged with the segment on working for Mr. Morning and thought that might recur, but it doesn’t. Many of the secondary characters are grotesque, whereas Iris is the intellectual waif trying to make her way in the cruel city, almost like a Dickens or Gissing (anti)hero.

It’s refreshing to get a female take on the Bildungsroman and a little bit of gender-bending with the cross-dressing. (Iris reminds me of Lauren Elkin’s Flaneuse.) The title felt like an enigma to me until close to the end, when it’s revealed to be a tool of sexual sadism. Indeed, each of the sections, in its own way, addresses male exploitation of and violence against women. Disappointingly, Iris remains defined by her relationships with men. She deserves better. Heck, she deserves a sequel! It’s interesting to see where Hustvedt got her start, but I didn’t warm to this as I did to later novels including What I Loved. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon: A Lurid Editions Reprint

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of Lurid Editions, which will focus on reprinting lesser-known and trailblazing 20th-century classics.

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of Lurid Editions, which will focus on reprinting lesser-known and trailblazing 20th-century classics.

Mary Louisa Gordon was a medical doctor and early graduate of the London School of Medicine for Women. She also served as a prison inspector and had a special concern for the plight of female prisoners; another of her works was Penal Discipline (1922). Chase of the Wild Goose was published when she was 75. She underwrote the book to keep it in print until her death in 1941. A word-of-mouth success, it sold reasonably well in those first years.

I’d encountered the Ladies of Llangollen a couple of times before, in nonfiction: in The Art of the Wasted Day by Patricia Hampl, where they are among her exemplars of solitary, introspective living; and in Sign Here If You Exist and Other Essays by Jill Sisson Quinn, where, in the way that they blur the lines between romance and friendship, they presage her experience with an intimate female friend. This was a different way to explore their story.

Portrait of The Rt. Honble. Lady Eleanor Butler & Miss Ponsonby ‘The Ladies of Llangollen’. By James Henry Lynch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (Wearing their customary plain riding habits and top hats.)

“The two heroines of this story, the Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby, have a remarkable history. They achieved fame at a stroke. They made a noise in the world which has never since died out, and which we, their spiritual descendants, continue to echo.”

These are the opening lines of what, in its first half, is a fairly straightforward chronological account of the protagonists’ lives, from their first meeting to when they flee to Wales to set up house together at Plas Newydd. They grow up in Ireland and, although their prospects differ – EB has a wealthy upbringing at Kilkenny Castle, whereas teenage SP has recently lost her mother and is being passed around relatives and acquaintances – both are often told that marriage is the only viable option. The eccentric spinster stereotype is an unkind one, but one EB is willing to risk. In one terrific scene, she shames her archbishop great-uncle for being just like everyone else and threatening to sell her to the highest bidder in matrimony. Still, the notion persists that if only the right man comes courting, they’ll change their tune.

At their first meeting EB and SP engage in an intense discussion of the possibilities for women, and within two weeks they’re already pledging to be together forever: “I think that nothing cheap, or second-rate, or faute de mieux, will ever do for you or me … We think—you and I—that we want something strange and exceptional, but something different may be ordained for us,” Eleanor says to Sarah. “From now onwards I… won’t you keep me… in your heart?” Sarah asks in parting. Eleanor replies, “I think you have been in it since before we were born.”

The strength of that romantic conviction that they are fated for each other keeps them going despite difficulties – EB’s father disowns her and cuts her off, which has inevitable financial implications, though she had already bought Plas Newydd outright; and for both of them, leaving Ireland is a wrench because they feel certain that they can never go back.

Plas Newydd. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

By Part II, the erstwhile fugitives, settled into local life in North Wales, enter into a sedate middle age of visitors and correspondence. Much of the material for this section is drawn from the journal EB kept. Part III is where things get really interesting: in a metafictional twist, Gordon herself enters the narrative as she meets and converses with the long-dead Ladies at their house, reflecting on the social changes that have occurred since their time.

As the Afterword by Dr Nicola Wilson notes, Chase of the Wild Goose is creative nonfiction in the same vein as Orlando, building on real-life figures and relationships in a way that must have seemed ahead of its age, not least for how it looks back to venerate queer foremothers. Although there are long stretches of the book that are tedious with biographical detail and melodramatic speeches, there is enough in the way of convincing dialogue and scenes to make up for that. While I feel the novel probably has more to offer to academics and those with a particular interest in its subjects than to general readers, I was pleased to be able to experience a rediscovered classic. I marvelled every time I reminded myself that this largely takes place in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. Gordon ably reproduces the diction and mores of the Ladies’ time, but her modernist intrusion takes it beyond pastiche.

As for the title, I’m most accustomed to the wild goose as a metaphor for the Holy Spirit in Celtic Christian iconography, but of course it is also a pun on the proverbial wild-goose chase. Gordon nods to both connotations; the phrase appears several times in the text and is the protagonists’ private term for their search for a life together – for liberty and for love. You have to cheer for them, achieving what so few could in their time. Here’s to you, Ladies!

With thanks to D-M Withers and Lurid Editions for the free copy for review.

A first read for Karen and Lizzys #ReadIndies challenge. I will hope to add many more before the end of the month!

Liz has also reviewed the novel.

For more information, do also read this fascinating Guardian article.

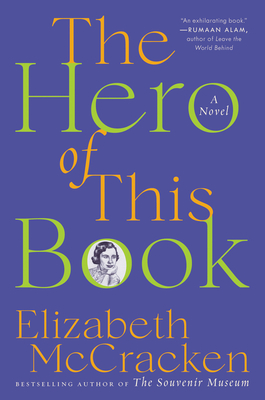

The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken (#NovNov22)

The hero of this book is Elizabeth McCracken’s mother, Natalie (1935–2018).

Is it autofiction or a bereavement memoir? Both and neither. It’s clear that the subject is her late mother, but less obvious that the first-person narrator must be McCracken or that the framework she has set up – an American writer wanders London, seeing the sights but mostly reminiscing about her mother – is other than fiction.

In August 2019, the writer rents a hotel room in Clerkenwell and plays the flaneuse around the city. Her tour takes in the London Eye, a ferry ride across the Thames from one Tate museum to another, a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and so on. London had been a favourite destination for her and her mother, their final trip together falling just three years before. McCracken is so funny on the quirks of English terminology – and cuisine:

The least appetizing words in the world concern English food: salad cream, baps, butties, carvery, goujons.

Always, though, her thoughts return to her mother, whom she describes through bare facts and apt anecdotes. A twin born with cerebral palsy. A little disabled Jewish lady with unmanageable hair. An editor and writer based at Boston University. Opinionated, outspoken, optimistic; set in her ways. Delightful and maddening in equal measure – like all of us. (“All mothers are unknowable, being a subset of human beings.”)

The writer’s parents were opposites you never would have paired up. (Her father, too, is gone now, but his death is only an aside here.) Their declines were predictably hard to forecast. The New England family home has been emptied and is now on the market; an excruciating memory resurfaces from the auction of the contents.

As well as a tribute to a beloved mother and a matter-of-fact record of dealing with ageing parents and the aftermath of loss, this is a playful cross-examination of literary genres:

I hate novels with unnamed narrators. I didn’t mean to write one.

My mother was known to say with disgust, “Oh, those people who write memoirs about the worst thing that ever happened to them!” I said it, too. Some years later a terrible thing happened to me, and there was nothing to do but to write a memoir.

That was An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination, about the stillbirth of her first child. As bereavement memoirs go, it’s one of the very best and still, 10 years after I read it, stands as one of my absolute favourite books, with some of the strongest last lines out there. McCracken has done it again, producing a book that, though very different in approach and style (this time reminding me most of Jenny Offill’s Weather), somehow achieves the same poignancy and earns a spot in my personal hall of fame, for the reasons you’ll see below…

The hero of this review is my mother, Carolyn (1947–2022).

I find it hard to believe that she’s been gone for three and a half weeks already. One week after her funeral, I was reading this book on my Kindle in London, waiting for a climate march to start. So many lines penetrated my numbness; all could pertain to my own mother:

[Of a bad time when her mother was in hospital with an infection] Those days were a dress rehearsal for my mother’s easy actual death seven years later.

My mother was a great appreciator. It was a pleasure to take her places, because she enjoyed herself so much and so audibly. That was her form of gratitude.

My mother all by herself was a holiday, very good at buying presents and exceptional at receiving them.

Quirky, somebody once called my mother. What a colossally condescending word: I hate it. It means you’ve decided that you don’t have to take that person seriously.

My mother’s last illness was a brain aneurysm.

The dead have no privacy left, is what I’ve decided.

The adrenaline of a busy week back in the States – meeting up with family members, writing and delivering a eulogy, packing up most of her belongings, writing thank-you notes, starting on paperwork (“sadmin”) – has long worn off and I’m back into my routines of work and volunteering and trying to make our house habitable as winter sets in. It would be easy to feel as if that middle-of-the-night phone call in late October, and everything that followed, was merely a vivid, horribly extended dream and that tomorrow she’ll pop back up in my inbox with some everyday gossip.

Reminders of her are everywhere if I look. Clothes she gave me, or I inherited from her, or she sent me the money to buy; a box of extra-strong Earl Grey teabags, left over from what we handed out along with memorial cards at the visitation; her well-worn Bible and delicate gold watch; the five boxes of journals in my sister’s basement – 150 volumes each carefully labelled with a number and date range. I have the first few and the last, incomplete one here with me now. What a trove of family stories, precious or painful, await me when I’m strong enough to read them.

With Thanksgiving coming up tomorrow – a whole holiday devoted to gratitude! nothing could more perfectly suit my mother – I’m grateful for all of those mementoes, and for the books that are getting me through. Starting with this one. [192 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Booker Prize Longlist Reading & Shortlist Predictions

I’ve polished off another four from the Booker Prize longlist (my initial reactions and excerpts from existing reviews are here), with one more coming up for me next month.

Trust by Hernan Diaz

“History itself is just a fiction—a fiction with an army. And reality? Reality is a fiction with an unlimited budget.”

My synopsis for Bookmarks magazine:

Set in the 1920s and 1930s, this expansive novel is about the early days of New York City high finance. It is told through four interlocking narratives. The first is Bonds, a novel by Harold Vanner, whose main character is clearly based on tycoon Andrew Bevel. Bevel, outraged at his portrayal as well as the allegation that his late wife, Mildred, was a madwoman, responds by writing a memoir—the book’s second part. Part 3 is an account by Ida Partenza, Bevel’s secretary, who helps him plot revenge on Vanner. In the final section, Mildred finally gets her say. Her journal caps off a sumptuous, kaleidoscopic look at American capitalism.

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of To Paradise), they’re ever so dull to read.

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of To Paradise), they’re ever so dull to read.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet

That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to His Bloody Project. (Public library)

That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to His Bloody Project. (Public library)

Those two are both literary show-off stuff (the epistolary found documents strategy, metafiction): the kind of book I would have liked more in my twenties. I’m less impressed with games these days; I prefer the raw heart of this next one.

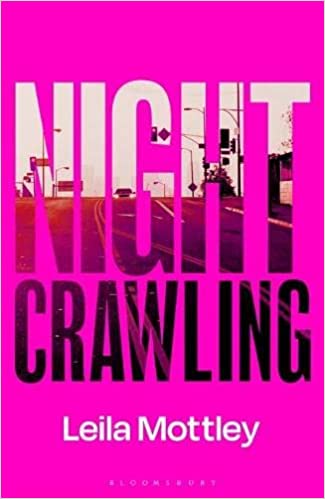

Nightcrawling by Leila Mottley

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor.

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor.

I loved her relationships with Trevor, her best friend Alé (they crash funerals for the free food), and trans prostitute Camila, and the glimpses into prison life and police corruption. This doesn’t feel like misery for the sake of it, just realistic and compassionate documentation. There were a few places where I felt the joins showed, like a teacher had told her she needed to fill in some emotional backstory, and I noticed an irksome habit of turning adjectives into verbs or nouns (e.g., “full of all her loud,” “the sky is just starting to pastel”); perhaps this is an instinct from her start in poetry, but it struck me as precious. However, this is easily one of the more memorable 2022 releases I’ve read, and I’d love to see it on the shortlist and on other prize lists later this year and next. (Public library)

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

The difficulty of ever really knowing another person, or even understanding oneself, is one of Strout’s recurring messages. There are a lot of strong lines and relatable feelings here. What I found maddening, though, is Lucy’s tentative phrasing, e.g. “And I cannot explain it except to say—oh, I don’t know what to say! Truly, it is as if I do not exist, I guess is the closest thing I can say.” She employs hedging statements like that all the time; it struck me as false that someone who makes a living by words would be so lacking in confidence about how to say what she means. So I appreciated the psychological insight but found Lucy’s voice annoying, even in such a short book. (Public library)

A Recap

I’ve read 6 of the 13 at this point, have imminent plans to read After Sappho for a Shelf Awareness review, and would still like to read the Mortimer if my library system acquires it. The others? Meh. I might consider catching up if they’re shortlisted.

My book group wasn’t chosen to shadow the Booker Prize this year, which is fair enough since we already officially shadowed the Women’s Prize earlier in the year (here are the six successful book clubs, if you’re interested). However, we have been offered the chance to send in up to five interview questions for the shortlisted authors. The Q&As will then be part of a website feature. And I was pleasantly surprised to see that my non-holiday snap of a Booker Prize nominee turned up in this round-up!

Here’s my (not particularly scientific) reasoning for what might make the shortlist:

A literary puzzle novel

Trust by Hernan Diaz or Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet

- Trust feels more impressive, and timely; GMB already had his chance.

A contemporary novel

Nightcrawling by Leila Mottley or Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

- Oh William! is the weakest Strout novel I’ve read. Mottley’s is a fresh voice that deserves to be broadcast.

A satire

The Trees by Percival Everett or Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka

- Without having read either, I’m going to hazard a guess that the Everett is too Ameri-centric/similar to The Sellout. The Booker tends to reward colourful Commonwealth books. [EDITED to add that I forgot to take into my considerations Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo; while it doesn’t perfectly fit this category, as a political allegory it’s close enough that I’ll include it here. I would not be at all surprised if it made the shortlist, along with the Karunatilaka.]

A couple of historical novels

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler or After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz

and/or

A couple of Irish novels

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan or The Colony by Audrey Magee

- I’m hearing such buzz about the Magee, and there’s such love out there for the Keegan, that I reckon both of these will make it through.

The odd one out?

Treacle Walker by Alan Garner or Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer

- Maybe nostalgia will spur the judges to give Garner a chance in his 80s.

My predicted shortlist:

On Tuesday evening we’ll find out if I got any of these right!

What have you read from the longlist? What do you most want to read, or see on the shortlist?

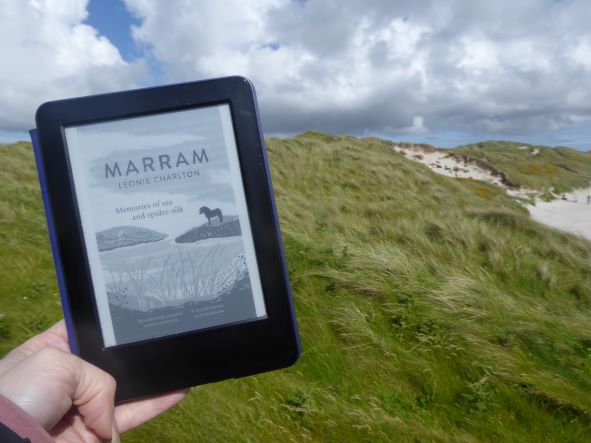

20 Books of Summer, 8–10: Marram, Orchid Summer, and Bonsai

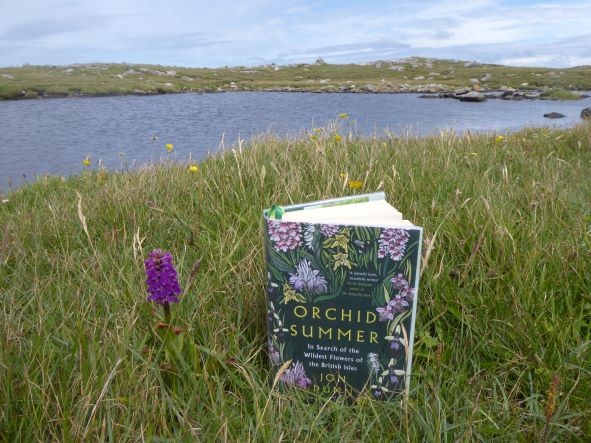

Halfway through my flora-themed reading challenge with less than half of the summer left to go. However, I’m actually partway through another seven relevant reads, so I’m confident I’ll get to 20. The sticking point for me, as always, is finishing what I’ve started!

Today I have brief responses to the two nature/travel quest memoirs I took with me to the Outer Hebrides, plus a forthcoming Chilean novella about how a relationship is to be memorialized.

Marram: Memories of Sea and Spider Silk by Leonie Charlton (2020)