June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Recent Poetry Releases by Clarke, Galleymore, Hurst, and Minick

All caught up on March releases now. There’s a lot of nature and environmental awareness in these four poetry collections, but also pandemic lockdown experiences, folklore, travel, and an impasse over whether to have children. Three are from Carcanet Press, my UK poetry mainstay; one was my introduction to Madville Publishing (based in Lake Dallas, Texas). After my thoughts, I’ll give one sample poem from each book.

The Silence by Gillian Clarke

Clarke was the National Poet of Wales from 2008 to 2016. I ‘discovered’ her just last year through Making the Beds for the Dead, which shares with this eleventh collection a plague theme: there, the UK’s foot and mouth disease outbreak of 2001; here, Covid-19. Forced into stillness and attention to the wonders near home, the poet tracks nature through the seasons and hymns trees, sunsets and birds. Many poems are titled after months or calendar points such as Midsummer and Christmas Eve. She also commemorates Welsh landmarks and remembers her mother, a nurse.

The verse is full of colours and names of flora:

May-gold’s gone to seed, yellows fallen –

primrose, laburnum, Welsh poppy.

June is rose, magenta, purple,

pink clematis, mopheads of chives,

cranesbill flowering where it will,

a migration of foxgloves crossing the field.

(from “Late June”)

Even as she revels in beauty, though, she bears in mind suffering elsewhere:

There is time and silence

to tell the names of the dying, the dead,

under empty skies unscarred

by transatlantic planes.

(from “Spring Equinox, 2020”)

I noted alliteration (“At the tip of every twig, / a water-bead with the world in it”) and end rhymes (“After long isolation, in times like these, / in the world’s darkness, let us love like trees.”). All told, I found this collection lovely but samey and lacking bite. But Clarke is in her late eighties and has a large back catalogue for me to explore.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Baby Schema by Isabel Galleymore

I knew Galleymore’s name from her appearance at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2018. The University of Birmingham lecturer’s second collection is a slant-wise look at environmental crisis and an impending decision about motherhood. The title comes from Konrad Lorenz’s identification of features that invite nurture. Galleymore edges towards the satirical fantasies of Caroline Bird or Patricia Lockwood as she imagines alternative scenarios of caregiving and contrasts sentimentality with indifference.

I knew Galleymore’s name from her appearance at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2018. The University of Birmingham lecturer’s second collection is a slant-wise look at environmental crisis and an impending decision about motherhood. The title comes from Konrad Lorenz’s identification of features that invite nurture. Galleymore edges towards the satirical fantasies of Caroline Bird or Patricia Lockwood as she imagines alternative scenarios of caregiving and contrasts sentimentality with indifference.

What is worthy of maternal concern? There are poems about a houseplant, a childhood doll, a soft toy glimpsed through a car window. A research visit to Disneyland Paris in the centenary year of the Walt Disney Company leads to marvelling at the surreality of consumerism. Does cuteness merit survival?

Because rhinos haven’t adopted the small

muscle responsible for puppy dog eyes,

the species goes bankrupt.

Its regional stores close down.

(from “The Pitch”)

The speaker acknowledges how gooey she goes over dogs (“Morning”) and kittens (“So Adorable”). But “Mothers” and “Chosen” voice ambivalence or even suspicion about offspring, and “Fable” spins a mild nightmare of infants taking over (“babies nesting in other babies / of cliff and reef and briar”). By the time, in “More and More,” she pictures a son, “a sticky-fingered, pint-sized / version of myself toddling through the aisles,” she concludes that we live in a depleted “world better off without him.”

Extinction and eco-grief on the one hand, yes, but the implacability of biological cycles on the other:

That night, when I got home, I learnt

a tree frog species had been lost

and my body was releasing its usual sum of blood.

I only had a few years left, my mother

often warned

(from “Release”)

Sardonic yet humane, and reassuringly indecisive, this is a poetry highlight of the year so far for me. I’ll go back and find her debut, Significant Other, too.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Iron Bridge by Rebecca Hurst

Manchester-based Hurst’s debut full-length collection struck me first for its gorgeous nature poetry arising from a series of walks. Most of these are set in Southern England in the current century, but date and location stamps widen the view as far as 1976 in the one case and Massachusetts in the other. The second section entices with its titles drawn from folklore and mythology: “How the Fox Lost His Brush,” “The Animal Bridegroom,” “The Needle Prince,” “And then we saw the daughter of the minotaur.”

An unexpected favourite, for its alliteration, assonance and book metaphors in the first stanza, was “Cabbage”:

Slung from a trug it rumbles across

the kitchen table, this flabby magenta fist

of stalk and leaf, this bundle of pages

flopping loose from their binding

this globe cleaved with a grunt leaning hard

on the blade

Part III, “Night Journeys,” has more nature verse and introduces a fascination with Russia that continues through the rest of the book. I loved the mischievous quartet of “Field Notes” prose poems about “The careless lover,” “The theatrical lover,” “The corresponding lover,” and “The satisfying lover” – three of them male and one female. The final section, “An Explorer’s Handbook,” includes found poems adapted from the published work of travel writers contemporary (Christina Dodwell) and Victorian (nurse Kate Marsden). Another series, “The Emotional Lives of Soviet Objects,” gives surprising power to a doily, a slipper and a potato peeler.

There’s a huge range of form and subject matter here, but the language is unfailingly stunning. Another standout from 2024 and a poet to watch. From my other Carcanet reading, I’d liken this most to work by Laura Scott and Helen Tookey.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Intimacy of Spoons by Jim Minick

A new publisher and author for me. Minick has also published fiction and nonfiction; this is his third poetry collection. Between the opener, “To Spoon,” and the title piece that closes the book, there are five more spoon-themed poems that create a pleasing thematic throughline. Why spoons? Unlike potentially violent knives and forks, which cut and spear, spoons are gentle. They’re also reflective surfaces, and because of their concavity, they can hold things and nestle together. In “The Oldest Spoon,” they even bring to mind a guiding constellation.

A new publisher and author for me. Minick has also published fiction and nonfiction; this is his third poetry collection. Between the opener, “To Spoon,” and the title piece that closes the book, there are five more spoon-themed poems that create a pleasing thematic throughline. Why spoons? Unlike potentially violent knives and forks, which cut and spear, spoons are gentle. They’re also reflective surfaces, and because of their concavity, they can hold things and nestle together. In “The Oldest Spoon,” they even bring to mind a guiding constellation.

The rest of the book is full of North American woodland and coastal scenes and wildlife. Minick displays genuine affection for and familiarity with birds. He is also realistic in noting all that is lost with habitat destruction and dwindling populations. “Lasts” describes the bittersweet sensation of loving what is disappearing: “Goodbye, we always say too late, / or we never get a chance to say at all.” He wrestles with human mortality, too, through elegies and minor concerns about his own ageing body. I loved the seasonal imagery and alliteration in “Spangled” and the Rolling Stones refrain to “Gas,” about boat-tailed grackles encountered in the parking lot at a Georgia truck stop.

Why not embrace all that is ugly

& holy & here—the grackle’s song

that isn’t a song, a breadcrumb dropped,

the shiny ribbon of gasoline

that will get me closer to home.

For something a bit different, I appreciated the true-crime monologue of “Tim Slack, the Fix-It Man.” With playfulness and variety, Minick gives us new views on the everyday – which is exactly why it is worth reading poetry.

With thanks to Madville Publishing for the free e-copy for review.

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Reading Ireland Month: Seán Hewitt, Maggie O’Farrell

Reading Ireland Month is hosted each year by Cathy of 746 Books. I’m wishing you all well on St. Patrick’s Day with this first of two planned tie-in posts. Today I have a poetry collection that sets grief and queer longing amid nature, and my last unread novel – a somewhat middling one, unfortunately – by one of my favourite authors.

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt (2024)

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

In “Two Apparitions,” the poet’s late father seems visible again. Many of the scenes take place at dusk or dark. There’s a layer of menace to “Night-Scented Stock,” about an abusive relationship, and the account of a slaughter in “Pig.” But the stand-out is “We Didn’t Mean to Kill Mr Flynn,” based on the 1982 murder of a gay man in a Dublin park. Hewitt drew lines from court proceedings and periodicals in the Irish Queer Archive at the National Library of Ireland, where he was poet in residence. He voices first the gang of killers, then Flynn himself. The trial kickstarted Ireland’s Pride movement.

More favourite lines:

Come out, make a verb of me, let

my body do your speaking tonight —

(from “A Strain of the Earth’s Sweet Being”)

awestruck, bright,

a child in the bell-tower of beauty —

(from “Skylarks”)

Love, the world is failing:

come and fail with me.

(from “Nightfall”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

My Lover’s Lover by Maggie O’Farrell (2002)

I was so excited, a few years ago, to find battered copies of this and After You’d Gone in a local charity shop for 50 pence each, even though it appears a mouse had a nibble on one corner here. They were her first two books, but the last that I managed to source. Whereas After You’d Gone is a surprisingly confident and elegant debut novel about a woman in a coma and the family and romantic relationships that brought her to this point, My Lover’s Lover ultimately felt like a pretty run-of-the-mill story about two women finding out that (some) men are dogs and they need to break free.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

As in some later novels, there are multiple locales (here, NYC, the Australian desert, and China – a country O’Farrell often revisits in fiction) and complicated point-of-view shifts, but I felt the sophisticated craft was rather wasted on a book that boils down to a self-explanatory maxim: past relationships always have an effect on current ones. I also found the writing overmuch in places (“the grass swooshing, sussurating, cleaving open to her steps”; “letting fall a box of cereal into its [a shopping trolley’s] chrome meshing”; “her fingertips meeting the ceraceous, heated skin of his cheek”). However, this was an engrossing read – I read most of it in two days. It’s bottom-tier O’Farrell, though, along with The Distance Between Us and Hamnet – sorry, I know many adore it. (If you’re interested: middle tier = The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, Instructions for a Heatwave, her two children’s books, and The Marriage Portrait; top tier = After You’d Gone, The Hand that First Held Mine, This Must Be the Place, and I Am, I Am, I Am.)

I’ve gotten in the habit of reading one of Maggie O’Farrell’s works per year, so I will just have to reread my favourites until we get a new one. I’m already tapping a foot in impatience. (Secondhand from Bas, Newbury)

Have you read any Irish literature this month?

Review: The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley (2023)

The Nero Book Awards category winners will be announced on Tuesday. I haven’t had a chance to read as many of the nominees as I would like, but I’m catching up on one that I’ve wanted to read ever since I first heard about it early last year. Even though Stephen Collins sums up about my feelings about coldwater swimming well in this cartoon –

– I was drawn to The Tidal Year for several reasons. First off, I’ll read just about any bereavement memoir going. Second, I love following along on a year challenge. Third, even though I haven’t been much of a swimmer since childhood, I appreciate how outdoor swimming combines observation of nature and the seasons with achievable bodily exploits; you don’t have to be an exercise nut or undergo lots of training to get into it. There was a spate of swimming memoirs back in 2017, including Jessica J. Lee’s superb Turning and Ruth Fitzmaurice’s I Found My Tribe. Headlines often tout the physical benefits of coldwater swimming, but it’s the emotional benefits that Bromley emphasizes in this record of facing grief and opening up to love.

Bromley was the middle of five children but her boisterous family’s dynamic went out of kilter when her younger brother Tom was diagnosed with bone cancer and died at age 19. Suddenly she could hardly talk to her mother, let alone to Tom’s twin, Emma. Isolated in London, where she worked in music journalism, she roped her friend Miri into wild swimming excursions and threw herself into Internet dating. She and Miri concocted a plan to swim in all of Britain’s mainland tidal pools (saltwater enclosed by manmade elements) in a year; she started seeing Jem, a free-spirited documentary filmmaker – but also Flip, a Black actor she met when he came to buy her neighbour’s antique chairs; he nicknamed her “Poet” and encouraged her in her writing.

Each short chapter is identified by a place name and its geographical coordinates. Most often, these correspond to a swimming destination, but they can also be clues to interludes or flashbacks, whether set in London (“Jem’s Skylight”), on the last night she spent by Tom’s hospital bedside, or at the Brecon Beacons home her parents moved to after Tom’s death. A lot of the tidal pools are in Devon and Cornwall, but she and Miri also make expeditions to Scotland and Wales and elsewhere along the south coast.

At a certain point Bromley realizes that they aren’t going to hit every single pool before the year is over, but the goal starts to matter less than the slow internal transformation that’s taking place. “Swimming had been a way for me to rediscover my body as a place of power, play and movement.” We see the gradual shifts: she’s more able to talk about Tom, she commits to her writing through a Cambridge course, she’s a supportive big sister to Emma, and she breaks it off with one of the boyfriends.

I had to suppress my judgemental side here. I know monogamy is not a universal value, especially among a younger generation, and Bromley does acknowledge that she was behaving badly in stringing two partners along – grief leads people to make decisions they might not normally. The other niggle for this pedantic proofreader was the non-standard way of introducing dialogue. Bromley chose to put all dialogue in italics – fine with me – but doesn’t consistently bracket phrases with “I said” or “she asked.” Usually it’s clear enough, but sometimes the interruption of speech with gesture is downright maddening, e.g., “There’s this, I blew on the tea, well inside me” and “It’s magic isn’t it, Miri rolled down her window”.

But I was (mostly) able to excuse this stylistic quirk because Bromley writes so acutely about herself and others, giving a lucid sense of the passage of time and the particularities of place. She’s observant and funny, too. “I find what people often mean when they say ‘resilient’ is that they want people to be good at suffering in silence.” Youthful, playful, sexy: those are unusual characteristics for a book on the fringes of nature writing. The voice was distinctive enough that, though I’ve rarely met a 400+-page book that couldn’t stand to be closer to 300, I thoroughly enjoyed my time spent with it.

The Nero Awards judges chose an all-female inaugural shortlist made up of four works of opinionated nonfiction. I’ve read the first 42 pages of Undercurrent, Natasha Carthew’s memoir of growing up in poverty in Cornwall, and will probably leave it there; I didn’t care for the writing in Fern Brady’s Strong Female Character, her memoir of being a young autistic woman (it’s said to be funny but I didn’t get the humour). Hags, Victoria Smith’s book about the societal marginalizing of older women, is the sort of book I’d skim from the library but am unlikely to read in its entirety. I would have been very happy for Bromley to win.

With thanks to Coronet (Hodder & Stoughton) for the free copy for review.

#WITMonth, Part II: Wioletta Greg, Dorthe Nors, Almudena Sánchez and More

My next four reads for Women in Translation month (after Part I here) were, again, a varied selection: a mixed volume of family history in verse and fragmentary diary entries, a set of nature/travel essays set mostly in Denmark, a memoir of mental illness, and a preview of a forthcoming novel about Mary Shelley’s inspirations for Frankenstein. One final selection will be coming up as part of my Love Your Library roundup on Monday.

(20 Books of Summer, #13)

Finite Formulae & Theories of Chance by Wioletta Greg (2014)

[Translated from the Polish by Marek Kazmierski]

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

(20 Books of Summer, #14)

A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast by Dorthe Nors (2021; 2022)

[Translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight]

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

You carry the place you come from inside you, but you can never go back to it.

I longed … to live my brief and arbitrary life while I still have it.

This eternal, fertile and dread-laden stream inside us. This fundamental question: do you want to remember or forget?

Nors lives in rural Jutland – where she grew up, before her family home was razed – along the west coast of Denmark, the same coast that reaches down to Germany and the Netherlands. In comparison to Copenhagen and Amsterdam, two other places she’s lived, it’s little visited and largely unknown to foreigners. This can be both good and bad. Tourists feel they’re discovering somewhere new, but the residents are insular – Nors is persona non grata for at least a year and a half simply for joking about locals’ exaggerated fear of wolves.

Local legends and traditions, bird migration, reliance on the sea, wanderlust, maritime history, a visit to church frescoes with Signe Parkins (the book’s illustrator), the year’s longest and shortest days … I started reading this months ago and set it aside for a time, so now find it difficult to remember what some of the essays are actually about. They’re more about the atmosphere, really: the remote seaside, sometimes so bleak as to seem like the ends of the earth. (It’s why I like reading about Scottish islands.) A bit more familiarity with the places Nors writes about would have pushed my rating higher, but her prose is excellent throughout. I also marked the metaphors “A local woman is standing there with a hairstyle like a wolverine” and “The sky looks like dirty mop-water.”

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Pharmakon by Almudena Sánchez (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore]

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

With thanks to Fum d’Estampa Press for the free copy for review.

And a bonus preview:

Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson]

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Coming out on 3 October from HarperVia. My full review for Shelf Awareness is pending.

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.” Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel,

Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel,  The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy)

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy) Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s]

Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s]  Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired  Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut,

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut,  The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy)

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy) Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like  The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun.

The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun. Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved  Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there (

Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there ( Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into…

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into… Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection,

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection,

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,  I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

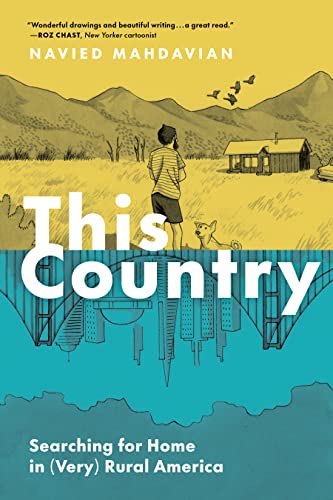

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on. Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs. Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A  This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is. A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home. The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to  A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.