#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

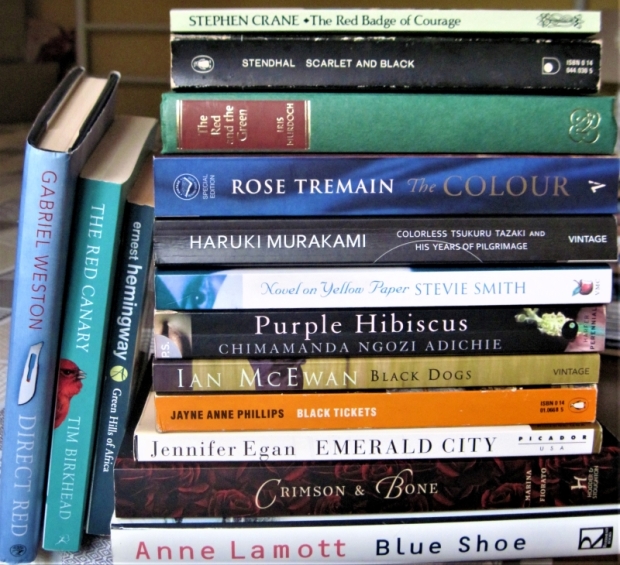

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

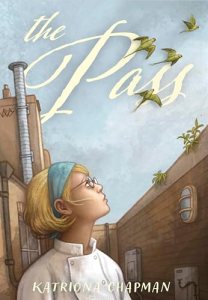

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

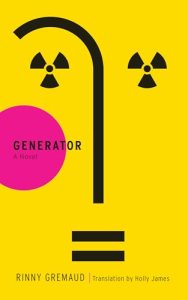

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

Book Serendipity, June to Mid-August 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A self-induced abortion scene in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

- A woman who cleans buildings after hours, and a character named Tova who lives in the Seattle area in A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Flirting with a surf shop employee in Sandwich by Catherine Newman and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Living in Paris and keeping ticket stubs from all films seen in Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer and The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick.

- A schefflera (umbrella tree) is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Company by Shannon Sanders.

- The Plague by Albert Camus is mentioned in Knife by Salman Rushdie and Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- Making egg salad sandwiches is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Sandwich by Catherine Newman.

- Pet rats in Stowaway by Joe Shute and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman. Rats are also mentioned in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Eels feature in Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma, Late Light by Michael Malay, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Atlantic City, New Jersey is a location in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Company by Shannon Sanders.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

- A New Zealand setting (but very different time periods) in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- A mention of Melanie Griffith’s role in Working Girl in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- A poet with a collection that was published on 6 August mentions a constant ringing in the ears: Joshua Jennifer Espinoza (I Don’t Want to Be Understood) and Keith Taylor (What Can the Matter Be?).

- A discussion of the original meaning of “slut” (a slovenly housekeeper) vs. its current sexualized meaning in Girlhood by Melissa Febos and Sandi Toksvig’s introduction to the story anthology Furies.

- An odalisque (a concubine in a harem, often depicted in art) is mentioned in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley.

- Reading my second historical novel of the year in which there’s a disintegrating beached whale in the background of the story: first was Whale Fall by Elizabeth O’Connor, then Come to the Window by Howard Norman.

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

- Her partner, a lawyer, is working long hours and often missing dinner, leading the protagonist to assume that he’s having an affair with a female colleague, in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- A fierce boss named Jo(h)anna in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- An OTT rendering of a Scottish accent in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A Padstow setting and a mention of Puffin Island (Cornwall) in The Cove by Beth Lynch and England as You Like It by Susan Allen Toth.

- A mention of the Big and Little Dipper (U.S. names for constellations) in Directions to Myself by Heidi Julavits and How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica.

- A mention of Binghamton, New York and its university in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- A character accidentally drinks a soapy liquid in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and one story of The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- The ex-husband’s name is Jonah in The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- The husband’s name is John in Dot in the Universe by Lucy Ellmann and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- An affair is discovered through restaurant receipts in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of eating fermented shark in The Museum of Whales You Will Never See by A. Kendra Greene and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of using one’s own urine as a remedy in Thunderstone by Nancy Campbell and Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa.

- The main character tries to get pregnant by a man even though one of the partners is gay in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Until the Real Thing Comes Along by Elizabeth Berg.

- Motherhood is for women what war is for men: this analogy is presented in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case, Parade by Rachel Cusk, and Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A woman bakes bread for the first time in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans.

- A gay couple adopts a Latino boy in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and one story of There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A man is haunted by things his father said to him years ago in Parade by Rachel Cusk and one story in There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- Two short story collections in a row in which a character is a puppet (thank you, magic realism!): The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer, followed by There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- A farm is described as having woodworm in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Parade by Rachel Cusk.

- Sebastian as a proposed or actual name for a baby in Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus and Birdeye by Judith Heneghan.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

20 Books of Summer, 9: Search by Michelle Huneven (2022)

Now this is what I want from my summer reading: pure pleasure; lit fic full of gossip and good food; the kind of novel I was always relieved to pick up and spend time with, usually as a reward for having gotten through my daily allotment in paid-review books and some more challenging reads. The Kirkus review was appealing enough to land this a place on my Most Anticipated list last year, but the only way to get hold of a copy was to spend my Bookshop.org voucher from my sister and have her bring it over in her suitcase in December.

The setup to Search might seem niche to many: a Southern California Unitarian church undergoes a months-long process to replace its retiring senior minister via a nationwide application process. But in fact it will resonate with, and elicit chuckles from, anyone who’s had even the most fleeting brush with bureaucracy – whether serving on a committee, conducting interviews, or trying to get a unanimous decision out of three or more people – and the framing story makes it warm and engrossing.

Dana Potowski is a middle-aged restaurant critic who has just released a successful cookbook based on what she grows on her smallholding. When she’s invited to be part of an eight-member task force looking for the right next minister for Arroyo Unitarian Universalist Community Church –

a “little chugger” of a church in a small unincorporated suburb of LA … three acres of raffish gardens, an ugly sanctuary, a deliquescing Italianate mansion, a jewel-box chapel used mostly for yoga classes

– she reluctantly agrees but soon wonders whether this could be interesting fodder for a second memoir (with identifying details changed, to be sure). You’ll quickly forget about the layers of fictionalization and become immersed in the interactions between the search committee members, who are of different genders, races and generations. They range from stalwart members, including a former church president and Dana the one-time seminarian, to a Filipino American recent Evangelical defector with a husband and young children.

Like the ministerial candidates, they’re all gloriously individual. You realize, however, that most of them have agendas and preconceived ideas. The church as a whole agreed that it wanted a gifted preacher and skilled site manager, but there’s also a collective sense that it’s time for a demographic change. A woman of colour is therefore a priority after decades of white male control, but a facilitator warns: “If you’re too focused on a specific category, you could overlook the best hire for your needs. Our goal is to get beyond thinking in categories to see the whole person.” Still, fault lines develop, with the younger contingent on the panel pushing for a thirtysomething candidate and the others giving more weight to experience.

Huneven develops all of her characters through the dialogue and repartee at the search committee’s meetings, which always take place over snacks, if not full meals with cocktails. Dana is not the only gifted home cook among the bunch (a section at the end gives recipes for some of the star dishes, like “Belinda’s Preserved Lemon Chicken,” “Dana’s Seafood Chowder,” and “Jennie’s Midmorning Glory Muffins”), and she also takes turns inviting her fellow committee members out on her restaurant assignments for the paper.

I was amazed by the formality and intensity of this decision-making process: a lengthy application packet, Skype interviews, watching/reading multiple sermons by the candidates, speaking to their references, and then an entire weekend of in-person activities with each of three top contenders. It’s clear that Huneven did a lot of research about how this works. The whole thing starts out casual and fun – Dana refers to the church and minister packets as “dating profiles” – but grows increasingly momentous. Completely different worship and leadership styles are at stake. People have their favourites, and with the future of a beloved institution at stake, compromise comes to feel more like a failure of integrity.

Keep in mind, of course, that we’re getting all of it from Dana’s perspective. She sets herself up as the objective recorder, but our admiration and distrust can only be guided by hers. And she’s a very likable narrator: intelligent and quick-witted, fond of gardening, passionate about food and spirituality, comfortable in her quiet life with her Jewish husband and her dog and donkeys. It’s possible not everyone will relate to her, or read meal plans and sermon transcripts as raptly, as I did. At the same time as I was totally absorbed in the narrative, I was also mentally transported to churches and pastors past, to petty dramas the ministers in my family have navigated, to the one Unitarian service I attended in Santa Fe in the summer of 2005… For me, this had it all. Both light and consequential; nostalgic and resolute about the future; frustrated with yet tender towards humanity. Delicious! I’ll seek out more by Huneven.

(New purchase with birthday money)

Review: Service by Sarah Gilmartin

The comparison with Sweetbitter, one of my favourite debuts of the past decade, drew me to Service, and it’s an apt one. Irish writer Sarah Gilmartin’s second novel is a before-and-after set partly in the stressful atmosphere of a fine dining restaurant in Dublin. Head chef Daniel Costello worked his way up from an inner-city childhood and teenage carvery-pub job to a two-Michelin-starred establishment known as T. But then came a fall: accusations of sexual assault from several female former employees led to the restaurant’s temporary closure and a high-profile court trial. Daniel maintains his innocence. His lawyer plans to cast shade on the lead waitress’ reputation, and question her failure to come forward until one year after the alleged rape.

Three alternating first-person narrators fill in the background of the macho restaurant world and the Costellos’ marriage. First is Hannah Blake, a former waitress who is not involved in the current lawsuit but has her own stories to tell about Daniel, who treated her as a protégée during the brief time she worked at T while she was a university student. “I’ve never felt as alive as I did that summer,” she writes; it was thrilling for a girl from Tipperary to be at the heart of Dublin’s culinary life and to have a world-leading chef believe her palate was worth training. We also hear from Daniel himself, and then his wife Julie, who begrudgingly supports Daniel but is furious with him for the negative attention the trial has brought her and their two sons. Some family members and neighbours have started avoiding them.

Gilmartin invites the reader to have sympathy for all the protagonists, even when it gets complicated. There was a point about three-quarters of the way through when I had to rethink who I felt sorry for and why. I would have liked a few more restaurant scenes to balance out the aftermath, but that is a minor quibble. This is a solid #MeToo novel with pacey, engaging writing and well-rounded characters. It’s made me eager to go back and catch up on the author’s debut, Dinner Party: A Tragedy.

My rating:

Service was published on 4 May. With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Update: Sarah Gilmartin kindly answered a question another blogger and I put to her, about how she decided on, and brought to life, these three narrators.

As a writer I’m drawn to ambivalence, ambiguity, grey areas. I’m curious about how people work, how they behave under pressure, when they think no one is watching, our public and private selves, all of that is the bones of literature. I wanted to tell a story about the abuse of power from different perspectives as I felt it was a subject that could potentially have multiple interpretations. I was interested in nuance and in leaving enough space for the reader to make up their own mind.

With Julie, I was struck that when you hear or read about MeToo stories in the media, one person you never or rarely hear from is the partner of the abuser. Certainly they’re not the most important voice in the scenario – the victim is – but you do think, or at least I do, what must it feel like for the partner of the predator? A woman whose life is being ripped apart in a different way by the same man. I wanted to know more about women in this position. In their own words. With Hannah, we have a different, younger, in some ways closer-to-the-action female perspective. Although she’s in her 30s now, in many ways Hannah is stuck in the past, her summer at the restaurant, as survivors of trauma often are, trying to get on with things but being continually brought back to the point where their lives were derailed. She’s also our guide to the restaurant world, which can often be very colourful and entertaining. Finally, with Daniel, for me the story didn’t feel cohesive without his perspective. He was a compelling character to write, a talented man, celebrated in his field, who has clearly defined private and public personas, and an aura of false humility; he’s a self-fashioned art monster. Then on another level, he’s a predator, with a huge amount of ego and vanity.

All three characters were interesting to me in their own right, which is key, and then they also had important things to contribute with regards to the subject matter of the book. I didn’t do a huge amount of research – read a lot about MeToo in the media, watched some Masterchef – but I worked as a waitress myself in my 20s so had a good idea of the world, the highs and lows, stresses and perks. Characters, once I have an idea of who they are, how they operate and what they want, tend to grow organically on the page. That’s the beauty of fiction!

#17–18: Marrow & The Hundred-Foot Journey

Almost there! Today I have a family memoir about the repercussions of cancer and a novel about an Indian chef who becomes a guardian of traditional French cuisine.

Marrow: A Love Story by Elizabeth Lesser (2016)

(20 Books of Summer, #17) I put this on the pile for my foodie-themed summer reading challenge because a marrow is an overgrown courgette (zucchini), but of course bone marrow is also eaten and is what is being referred to here. When they were in middle age and Lesser’s younger sister Maggie had a recurrence of her lymphoma, the author was identified as a perfect match to donate bone marrow. She charts the ups and downs of Maggie’s treatment but also goes deep into their family history: parents who rejected the supernatural in reaction to her mother’s Christian Science upbringing; a quartet of sisters who competed for love and attention; and different approaches to life – Maggie was a back-to-the-land Vermont farmer, nurse and botanical artist, while Elizabeth had bucked the trend by moving to New York City and exploring spirituality (she co-founded the Omega Institute, a holistic retreat center).

(20 Books of Summer, #17) I put this on the pile for my foodie-themed summer reading challenge because a marrow is an overgrown courgette (zucchini), but of course bone marrow is also eaten and is what is being referred to here. When they were in middle age and Lesser’s younger sister Maggie had a recurrence of her lymphoma, the author was identified as a perfect match to donate bone marrow. She charts the ups and downs of Maggie’s treatment but also goes deep into their family history: parents who rejected the supernatural in reaction to her mother’s Christian Science upbringing; a quartet of sisters who competed for love and attention; and different approaches to life – Maggie was a back-to-the-land Vermont farmer, nurse and botanical artist, while Elizabeth had bucked the trend by moving to New York City and exploring spirituality (she co-founded the Omega Institute, a holistic retreat center).

By including unedited “field notes” Maggie wrote periodically, Lesser recreates the drama and heartache of the cancer journey. She also muses a lot about attempts to repair family relationships through honest conversations and therapy. “Marrow” is not just a literal substance but also a metaphor for getting to the heart of what matters in life. I expect this memoir will be too New Age-y for many readers, but I appreciated its insights and the close sister bonds. I also loved the deckle edge and Maggie’s botanical prints on the endpapers. Recommended to fans of Elizabeth Gilbert and Anne Lamott.

Source: A clearance book from Blackwell’s in Oxford (bought on a trip with Annabel last summer)

My rating:

The Hundred-Foot Journey by Richard C. Morais (2008)

(20 Books of Summer, #18) From the acknowledgments I learned that this was written specifically to be filmed by the author’s friend Ismail Merchant; though Merchant died in 2005, it’s no surprise that it went on to become a well-received 2014 movie. I think the story probably worked better on the big screen, what with the Indian and French settings, the swirls of color and the bustle of restaurant kitchens. Still, I’d forgotten enough about the story line to enjoy the book, too.

(20 Books of Summer, #18) From the acknowledgments I learned that this was written specifically to be filmed by the author’s friend Ismail Merchant; though Merchant died in 2005, it’s no surprise that it went on to become a well-received 2014 movie. I think the story probably worked better on the big screen, what with the Indian and French settings, the swirls of color and the bustle of restaurant kitchens. Still, I’d forgotten enough about the story line to enjoy the book, too.

Hassan Haji, the narrator, is born in Mumbai, one of six children of a restaurateur, and has his interest in other food cultures awakened early by a memorable French meal (a common experience in several other books I’ve reviewed this summer: Kitchen Confidential, How to Love Wine and Tender at the Bone). After his mother’s death, the extended family relocates to London and then to provincial France. Stranded in Lumière by a car breakdown, the family decides to stay, opening a curry house across from a fine dining establishment run by Gertrude Mallory. Madame Mallory engages in a battle of wills with the uncouth new arrivals. It nearly takes a tragedy for her to get over her snobbishness and xenophobia and realize Hassan has a perfect palate. She takes him on as an apprentice and he makes the title’s 100-foot journey across the street to join her staff.

The film was undoubtedly a Helen Mirren vehicle, and the Lumière material from the middle of the book holds the most interest. The remainder goes more melancholy as Hassan loses many family members and colleagues and deplores the rise of French bureaucracy and fads like molecular gastronomy. Although he eventually earns a third Michelin star for his Paris restaurant, the 40-year time span means that the warm ending somewhat loses its luster. (I can’t remember if the film went so far into the future.) A pleasant summer read nonetheless.

Source: Free from a neighbor

My rating:

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,  The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues.

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues.

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to  Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis.

Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis. I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of  After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity.

After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity. We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s

We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s  This was consciously based on George Orwell’s

This was consciously based on George Orwell’s  I forgot to start it while I was there, but did soon afterwards: The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl, forthcoming in early 2024. When Stella’s elegant, aloof mother Celia dies, she leaves her $8,000 – and instructions to go to Paris and not return to New York until she’s spent it all. At 2nd & Charles yesterday, I also picked up a clearance copy of A Paris All Your Own, an autobiographical essay collection edited by Eleanor Brown, to reread. I like to keep the spirit of a vacation alive a little longer, and books are one of the best ways to do that.

I forgot to start it while I was there, but did soon afterwards: The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl, forthcoming in early 2024. When Stella’s elegant, aloof mother Celia dies, she leaves her $8,000 – and instructions to go to Paris and not return to New York until she’s spent it all. At 2nd & Charles yesterday, I also picked up a clearance copy of A Paris All Your Own, an autobiographical essay collection edited by Eleanor Brown, to reread. I like to keep the spirit of a vacation alive a little longer, and books are one of the best ways to do that. Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed

Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed  My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list. Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl. We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,